12 Guillain-Barré Syndrome Jennifer A. Frontera Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a heterogeneous group of immunemediated polyneuropathies with motor, sensory, and dysautonomic features. It is the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis in the United States, with a frequency of 1 to 3 per 100,000 people, and occurs in all age groups.1 The pathophysiology of GBS is thought to be related to molecular mimicry triggered by recent infection producing an autoimmune humeral and cell-mediated response against the ganglioside surface molecules of peripheral nerves (Table 12.1). There are several clinical subtypes of GBS (Table 12.2).

| Bacterial infection | Campylobacter jejuni Haemophilus influenzae Mycoplasma pneumoniae Borrelia burgdorferi |

| Viral infection | CMV EBV HIV (seroconversion) |

| Vaccines | Influenza vaccine Oral polio vaccine Menactra (Sanofi Pasteur, Lyon, France) meningococcal conjugate vaccine |

| Medications | Case reports related to streptokinase, isotretinoin, danazol, captopril, gold, heroin, and epidural anesthesia |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

| Subtype | Comments |

| Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP) | Most common subtype in the U.S. (85–90% of cases) 40% seropositive for Campylobacter jejuni Primarily demyelinating Progressive, symmetric weakness, absent/depressed deep tendon reflexes |

| Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) Acute sensorimotor axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) | Primary axonal injury 5–10% of U.S. cases 70–75% associated with preceding Campylobacter jejuni infection/diarrhea Up to 1/3 may be hyperreflexic Common in China, Japan, and Mexico GM1, GD1a, GalNac-GD1a, and GD1b antibodies |

| Miller Fisher syndrome | Triad of ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and areflexia 1/3 develop extremity weakness GQ1b antibodies in 90% 5% of cases in U.S. and 25% of cases in Japan Bickerstaff-Cloake encephalitis-brainstem encephalitis with ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, encephalopathy, and hyperreflexia associated with GQ1b antibodies may be a related entity. It responds to IVIG and plasma exchange. |

| Pharyngeal-cervical-brachial | Acute arm weakness and swallowing dysfunction May have facial weakness Leg strength and reflexes preserved |

| Paraparesis | Involvement limited to the lower extremities |

| Acute pandysautonomia | Sympathetic and parasympathetic involvement Orthostatic hypotension Urinary retention Diarrhea, abdominal pain, ileus, vomiting Pupillary abnormalities Variable heart rate Decreased sweating, salivation, and lacrimation Reflexes diminished Sensory symptoms |

| Pure sensory | Sensory ataxia Reflexes absent GD1b antibody |

Abbreviation: IVIG, intravenous high-dose immunoglobulin.

History and Examination

History

A typical history involves acute symmetric ascending weakness, often beginning in the proximal legs. Weakness beginning in the arms or face occurs in 10%, but eventually 50% of patients have facial or oropharyngeal weakness. Paresthesias in the hands and feet are reported in 80% of patients, as is lower back pain. Diplopia occurs in 15% due to oculomotor weakness. Dysautonomia occurs in 70% (tachycardia/bradycardia, wide swings in blood pressure, orthostasis, tonic pupils, urinary retention, ileus/constipation, hypersalivation, and anhidrosis). Respiratory failure requiring intubation occurs in 30%.2,3

- Assess for history of recent travel, viral illness, vaccine, or diarrhea.

Physical Examination

- Vital signs: Monitor for dysrhythmia, fluctuating blood pressure, hyperthermia, or hypothermia.

- Frequent checks of VC and NIF (every 2 to 6 hours)

Neurologic Examination

- Mental status: Normal unless CO2 retention leads to inattentiveness; delirium/hallucination/delusions have been reported in ICU GBS patients.

- Cranial nerves: Ptosis, ophthalmoparesis (diplopia), facial weakness, dysarthria, difficulty swallowing with pooling of secretions, tonic pupils can occur in patients with dysautonomia; rare papilledema has been reported.

- Motor: Ascending symmetric proximal >distal weakness, neck flexor weakness (C3-C5) correlates with respiratory capacity, hypotonia.

- Sensory: Can have abnormal proprioception, typically sensory <motor signs, sensory ataxia can occur

- Reflexes: Absent to reduced reflexes

- Cerebellar: Sensory ataxia may be confused for cerebellar ataxia.

Differential Diagnosis

- GBS

- Other polyneuropathies

- Acute motor neuropathies due to arsenic, lead poisoning, and porphyria

- Tick paralysis: Can mimic GBS closely with ascending paralysis, ophthalmoparesis, bulbar dysfunction, and reduced reflexes, but has a faster course of progression (hours to days) and is accompanied by ataxia, but no sensory symptoms.4 Complete cure can occur with tick removal.

- N-hexane (glue sniffing)

- Peripheral nerve vasculitis (presents as mononeuritis multiplex and can be due to polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.)

- Diphtheria: Caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, associated with a thick gray pharyngeal pseudomembrane, atrial-ventricular (AV) block, endocarditis, myocarditis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy with craniopharyngeal involvement, proximal >distal weakness, and decreased reflexes

- Ciguatera toxin (red snapper, grouper, barracuda) affects voltage gated sodium channels of muscles and nerves and produces a characteristic metallic taste in the mouth and hot-cold reversal.

- Neuropathy due to Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, paraneoplastic disease, and critical illness polyneuropathy

- Acute motor neuropathies due to arsenic, lead poisoning, and porphyria

- Neuromuscular junction disease. There is no sensory involvement in any disorder of neuromuscular transmission.

- Myasthenia gravis: Fatigable weakness, ptosis, nasal voice, ophthalmoparesis (diplopia), facial weakness, no pupillary involvement, fatiguing proximal >distal weakness, arm >leg weakness, normal reflexes.

- Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: Presynaptic autoimmune attack of voltage gated calcium channels, associated with cancer in 50 to 70% (typically small cell lung cancer), limb symptoms more prominent than ocular/bulbar symptoms at presentation, facilitation with exercise, autonomic dysfunction, and reduced reflexes. Respiratory failure is uncommon.

- Botulism: Neurotoxin produced from Clostridium botulinum, permanently blocks presynaptic acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction; causes symmetrical descending paralysis with dilated pupils (50%), no sensory deficit, and dysautonomia. Can be treated with trivalent equine antitoxin.

- Organophosphate toxicity (malathion, parathion, Sarin, Soman, etc.): Inactivates acetylcholine esterase, causing SLUDGE (salivation, lacrimation, urinary incontinence, diarrhea, gastrointestinal [GI] upset, emesis), miosis, bronchospasm, blurred vision, and bradycardia. Also causes confusion, optic neuropathy, extrapyramidal effects, dysautonomia, fasciculations, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, and weakness due to continued depolarization at the neuromuscular junction. Delayed polyneuropathy can occur 2 to 3 weeks after exposure. Treat with atropine, pralidoxime (2-PAM), and benzodiazepines. Avoid succinylcholine.

- Neurotoxic fish poisoning: Tetrodotoxin (pufferfish) and saxitoxin (red tide) both block neuromuscular transmission.

- Myasthenia gravis: Fatigable weakness, ptosis, nasal voice, ophthalmoparesis (diplopia), facial weakness, no pupillary involvement, fatiguing proximal >distal weakness, arm >leg weakness, normal reflexes.

- Muscle disorder: Critical illness myopathy and acute polymyositis can mimic GBS. Can differentiate with electromyography/nerve conduction study (EMG/NCS).

- Spinal cord disorder: Acute myelopathy can cause weakness, numbness, and acutely depressed deep tendon reflexes, along with bowel and bladder dysfunction. Back pain is common in GBS and spinal cord disorders. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can easily distinguish between the two (enhancement of nerve roots can occur with GBS).

- Brainstem disease with multiple cranial neuropathies (stroke, Bickerstaff-Cloake, rhombencephalitis, basilar meningitis, carcinomatous meningitis, Wernicke’s encephalopathy)

Life-Threatening Diagnosis Not to Miss

- Impending respiratory failure due to progressive neuromuscular disorder

- Spinal cord compression requiring surgical intervention

Diagnostic Evaluation

Clinical Criteria

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) criteria for diagnosis typically apply to acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP); patients with variants may not meet the criteria found in Table 12.3.5

| Required features | Progressive weakness of >1 limb, ranging from minimal weakness to quadriplegia, and variable trunk, bulbar, facial involvement or ophthalmoplegia Areflexia; distal areflexia with hyporeflexia at the knees and biceps is still consistent with the diagnosis of GBS |

| Supportive features | Progression of symptoms over days to 4 weeks and recovery starting 2–4 weeks after a plateau in symptoms Symmetrical involvement Mild sensory signs or symptoms CN involvement, bilateral facial weakness Autonomic dysfunction No fever at onset Elevated CSF protein with white cell count <10 mm3 EMG/NCS consistent with GBS: 80% have NCV slowing/conduction block Patchy reduction in NCV to <60% normal Distal motor latency increase up to 3x normal F waves prolonged 15–20% of patients have normal nerve conduction studies |

| Diagnosis less likely | Sensory level Asymmetry in exam Severe and persistent bowel and bladder dysfunction CSF with >50 white cells or polys |

Abbreviations: CN, cranial nerve; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EMG, electromyography; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; NCS, nerve conduction studies; NCV, nerve conduction velocity.

Laboratory Findings

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): Albuminocytologic dissociation (elevated CSF protein with normal white blood cells <10 cell/mm3) appears in 80 to 90% of patients within 1 week. CSF pleocytosis can occur with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-) associated AIDP.

- Antibodies: GQ1b (85 to 90% of patients with Miller Fisher variant); GM1, GD1a, GalNac-GD1a, and GD1b (associated with axonal variants); GT1a (associated with swallowing difficulty); GD1b (associated with pure sensory variant). Antibodies to Campylobacter jejuni, cytomegalovirus (CMV), HIV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and Mycoplasma pneumoniae can be tested. Antibody tests are expensive and are not routinely used.

- EMG/NCS: AIDP begins with demyelination at the nerve roots, and nerve conduction studies (NCS) reveal early prolonged F waves and absent H reflexes. Increased distal latencies, conduction block, and temporal dispersion can also be found, but significant slowing of conduction velocities is not seen until the third to fourth week. Sural sparing is typical, while median and ulnar sensory responses are affected. There is relative preservation of compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes and sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitudes. Needle exam has the highest yield if performed at least 3 weeks after symptom onset. In axonal variants, nerve conduction velocities are normal, distal latencies are not prolonged, and there is no temporal dispersion. CMAP amplitudes are reduced. Very low CMAP amplitude (<20% of normal) portends a poor prognosis (Table 12.4).

- MRI: Useful for ruling out cord compression, cauda equina syndrome, and other conditions. Spinal root enhancement can be seen in GBS (cauda equina nerve roots enhance in up to 83% of patients) and is due to disruption of the blood-CNS barrier.

- EMG/NCS: AIDP begins with demyelination at the nerve roots, and nerve conduction studies (NCS) reveal early prolonged F waves and absent H reflexes. Increased distal latencies, conduction block, and temporal dispersion can also be found, but significant slowing of conduction velocities is not seen until the third to fourth week. Sural sparing is typical, while median and ulnar sensory responses are affected. There is relative preservation of compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes and sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitudes. Needle exam has the highest yield if performed at least 3 weeks after symptom onset. In axonal variants, nerve conduction velocities are normal, distal latencies are not prolonged, and there is no temporal dispersion. CMAP amplitudes are reduced. Very low CMAP amplitude (<20% of normal) portends a poor prognosis (Table 12.4).

| EMG/NCS confirms AIDP | Multifocal demyelination |

| EMG/NCS highly suggestive of AIDP | Abnormal median SNAP and normal sural SNAP Rapid recovery of low distal CMAPs and SNAPs on subsequent studies |

| EMG/NCS suggestive of AIDP | Absent F waves with normal nerve conduction studies |

Abbreviations: AIDP, acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy; CMAP, compound muscle action potential; EMG, electromyography; NCS, nerve conduction studies; SNAP, sensory nerve action potential.

Treatment

Ventilation

Acute respiratory failure occurs in 30% of GBS patients. GBS patients with deterioration or impending crisis should be admitted to an intensive care unit because respiratory deterioration can be rapid. Although patients may be unable to handle secretions, glycopyrrolate should only be used with extreme caution, as it can lead to mucous plugging. VC and NIF should be measured every 2 to 6 hours, and prompt intubation should be pursued when NIF is worse than -20 cm H2O and/or VC <10 to 15 mL/kg or if there is a steadily declining NIF and/or VC. Succinylcholine should be avoided during intubation. The initial ventilator mode is typically “assist control/volume control.”

Patients should meet weaning criteria delineated in Chapter 17 prior to extubation. A bedside measure of the patient’s readiness for extubation is the ability to lift the head off the bed against resistance. Pressure support can be used as a weaning mode, but GBS patients should also undergo a T-piece or tube compensation trial prior to extubation.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

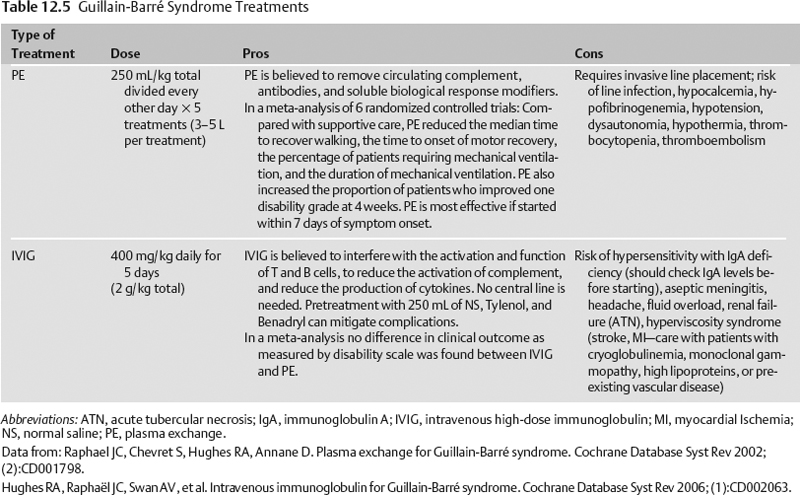

Specific treatment for Guillain-Barré syndrome is given in Table 12.5.6,7

American Association of Neurologists’ Practice Parameters8

- Treatment with IVIG or plasma exchange speeds recovery.

- IVIG and plasma exchange are equivalent.

- Plasma exchange is recommended for GBS patients unable to walk who start treatment within 4 weeks of onset of symptoms. Plasma exchange is also recommended for ambulatory patients who start treatment within 2 weeks of symptom onset.

- IVIG is recommended for nonambulatory GBS patients who start treatment within 2 or possibly 4 weeks from symptom onset.

- The time to onset of recovery is shortened by 40 to 50% by plasma exchange or IVIG.

- Combining IVIG and plasma exchange is not beneficial.

- Steroids alone are not beneficial.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree