Fig. 8.1

Sickle-cell anaemia in a 26-year-old male patient resulting in moyamoya syndrome. The TOF sequence shows bilateral terminal internal carotid artery occlusion (a hollow arrow, occluded right internal carotid artery) with dural collateral vessels derived from the middle meningeal arteries (a single arrow, right middle meningeal artery) and occipital arteries (a double arrows, right occipital artery). The FLAIR sequence shows numerous ischaemic parenchymal scars (b arrows)

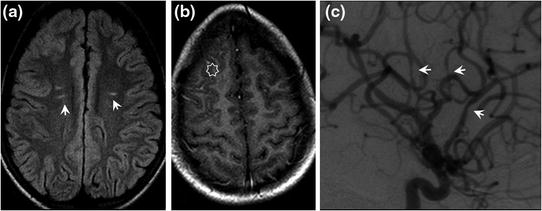

Fig. 8.2

Sickle-cell anaemia in a 12-year-old boy resulting in intracranial angiopathy. MRI signal abnormalities on the FLAIR sequence with focal white matter hyperintensities (a arrows). Right frontal pial contrast enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted SE sequences (b star). Arteriography shows segmental stenoses (c lateral view of right internal carotid artery: arrows)

Imaging

MRI

Moyamoya appearance: stenosis of internal carotid artery bifurcation on TOF sequence and development of choroidal and lenticulostriate collateral circulation visible on TOF sequences when the collateral circulation is well developed or on T2-weighted SE or gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequences in the form of hypointensities (T2) or punctate enhanced hyperintensities (gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images) of the basal ganglia. More distal focal narrowing of intracranial arteries, sometimes visible on TOF sequences. Atypical sites of aneurysm sometimes visible on TOF sequences or gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted volume-rendering images of distal vessels as intense nodular cortical enhancement.

Association of recent infarction visualized as focal hyperintensities on diffusion-weighted images with decreased ADC and old infarcts visualized as hyperintensities on FLAIR and T2-weighted images with increased ADC of the white matter or cortex predominantly adjacent to anterior watershed zones.

On T2-weighted GE images, focal hypointensities in the parenchyma or cortical sulci, sometimes visible as a result of haemorrhagic infarcts or sequelae of meningeal haemorrhage.

Angiography

Distal stenoses of internal carotid arteries with development of collateral circulation derived from anterior choroidal arteries, posterior communicating arteries and lenticulostriate arteries with the characteristic “puff of smoke” appearance. Multiple focal stenoses visible more distally in the intracranial arteries. Collateral circulation derived from the external carotid arteries (middle meningeal arteries ++) with transdural vascularization and development of the intracranial ophthalmic anastomotic network via ethmoidal arteries.

Treatment

Hydration and oxygenation during vaso-occlusive crises. Analgesics if necessary.

Blood transfusion and folic acid supplement to treat anaemia.

Blood transfusion to maintain haemoglobin S level below 30 % in order to reduce the risks of stroke and arterial deposits.

Prevention of risk factors for vaso-occlusive crisis (cold, altitude, dehydration).

Coagulopathies

Hereditary Thrombophilias

Autosomal dominant transmission.

Epidemiology

Incidence: 10 % of the population. Known risk factor for cerebral venous thrombosis. The role of hereditary thrombophilias in cerebral arterial disease remains controversial.

Aetiologies

Activated protein C resistance due to factor V Leiden mutation (20–25 % of thrombophilias, only in Caucasian subjects).

Prothrombin gene mutation.

Protein C deficiency.

Protein S deficiency.

Congenital antithrombin III deficiency.

Acquired antithrombin deficiencies are also observed: hepatocellular failure, heparin, nephrotic syndrome and protein C or S deficiency: VKA, vitamin K deficiency, DIC, hepatocellular failure.

Neurological Indications for Investigation of Hereditary Thrombophilia

Screening for hereditary thrombophilia must not be systematic, but should be reserved for:

patients with a history of cerebral venous thrombosis,

young subjects treated for ischaemic stroke:

patients with a personal or family history of venous thrombosis and a negative aetiological work-up for ischaemic stroke,

or in the presence of patent foramen ovale on TOE (paradoxical embolism responsible for ischaemic stroke).

Imaging

Nonspecific signs related to venous thrombotic and haemorrhagic phenomena: venous infarctions (Fig. 8.3), subarachnoid haemorrhages and intraparenchymal haematomas.

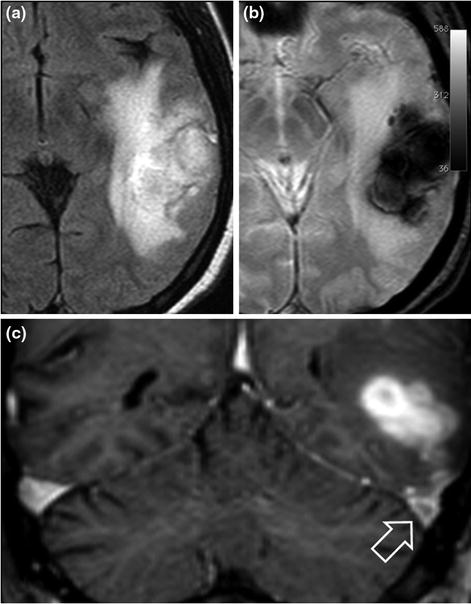

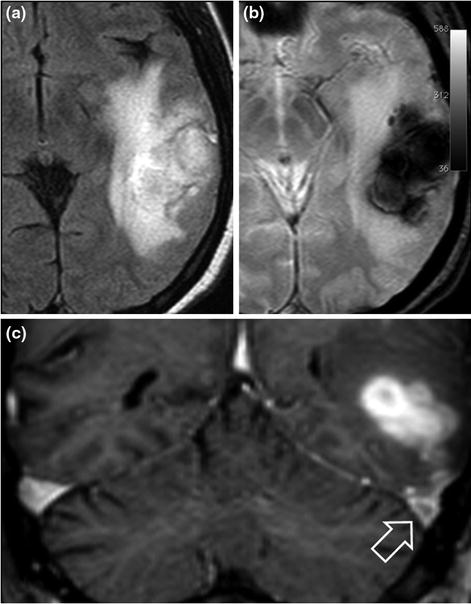

Fig. 8.3

45-year-old male patient with temporo-occipital intraparenchymal haematoma secondary to cerebral venous thrombosis. The haematoma is hyperintense on the FLAIR sequence (a) and hypointense on the T2*-weighted images (b). The thrombus is visible in the left transverse sinus (c coronal gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images, hollow arrow). Laboratory tests revealed a factor II mutation and positive antiphospholipid antibodies

Treatment

Long-term effective anticoagulant therapy should be considered, depending on the type of abnormality detected (not all hereditary thrombophilias are associated with the same risk of thrombosis).

At least: antiplatelet therapy.

Propose family screening.

Subacute or Chronic DIC

Formation of blood clots triggered by a systemic inflammatory response induced by cytokines, leading to consumption of platelets and clotting factors. Fibrin deposits in small and medium-sized vessels leading to disseminated infarcts. DIC is secondary to an underlying disease.

Clinical Features

Known active cancer or first sign of an underlying cancer.

General malaise.

Features of encephalopathy or focal deficits associated with multiple relapsing ischaemic strokes.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Thrombocytopenia.

Prolonged APTT.

Decreased fibrinogen levels.

Decreased factor V activity.

High D-dimer levels, presence of soluble complexes (FDP).

In chronic DIC, platelets, fibrinogen and PT can be borderline, hence the importance of D-Dimers and repeated laboratory tests (laboratory test results can return to normal in response to even preventive doses of heparin [LMWH]).

Imaging

Multiple, nonspecific, small cerebral infarctions (Fig. 8.4).

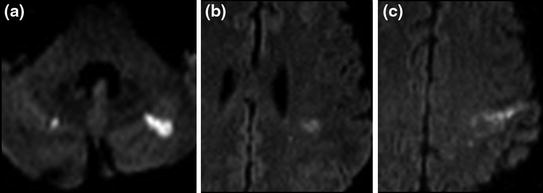

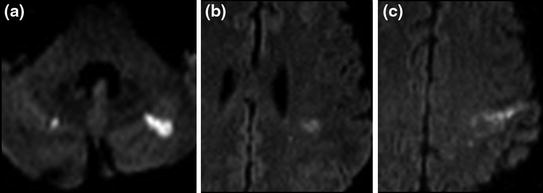

Fig. 8.4

57-year-old male patient with chronic DIC in a context of lung cancer with pancreatic, liver and bone metastases. Multiple microinfarctions affecting several vascular territories, visualized as focal hyperintensities on diffusion-weighted images (a, b and c)

Associated systemic infarctions. Subarachnoid haemorrhages and intraparenchymal haematomas and sometimes intra-ocular haemorrhage may be observed.

Treatment

Treatment of the cause. Heparin can correct laboratory abnormalities but is only partially effective to prevent recurrence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree