6 Headache

Introduction

Headache is the most common neurological condition for which consultation is sought.1 The approach adopted in this review offers a clinical strategy to guide the family doctor without need to resort to the International Headache Society (IHS) classification.2

This should not be interpreted as undervaluing that classification,2 which is pivotal in allowing international consensus necessary for clinical research and trials, but clinical trials do not necessarily reflect everyday practice. The IHS criteria2 allow researchers around the world to recruit patients with rare headache diagnoses to trial novel treatments with the ability to recruit sufficient patients to achieve statistical power. While this is fundamental for scientific progress, it does little to assist the general practitioner who sees very few cases of such conditions; for example, cluster headache. Cluster headache was not randomly chosen for this example, but rather because it is diagnosed more often by family doctors than neurologists, and affects less than 1% of those with headaches.3

Broad-Brushed Clinical Approach

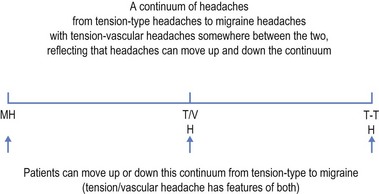

A practical, if unscientific, approach to headache is to consider that primary headaches lie on a continuum (see Fig 6.1). At one end of this continuum lies tension-type headaches, while at the other is migraine (with or without aura). In the middle is what might be called tension-vascular headache with features of both, a term excluded from the IHS classification.2

Differentiating tension-type headache from migraine

This starts with a concise history dating from the onset of the headaches. The doctor needs to know: how long the patient has had headaches; where they occur in the head (unilateral, bilateral, frontal, occipital, vertex or completely generalised); the nature of the pain (be it constant and gripping, throbbing and pulsating, or stabbing and lancinating); associated features (visual symptoms, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms of nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia or osmophobia); the frequency and duration; and precipitating and relieving factors. This will assist in differentiating migraine from tension-type headache (see Table 6.1).

TABLE 6.1 Differentiation between migraine and tension-type headaches

| Migraine | Tension headache |

|---|---|

| Unilateral—often in the temple | Bilateral—like a band or in both temples |

| Throbbing pain—pulsating | Tight, gripping pain—constant |

| May be provoked by times of maximal stress | |

| Either no visual symptoms or simply some blurring of vision | |

| Nausea and vomiting is common | Nausea may be present but rarely vomiting |

| May be provoked by alcohol | May be eased by alcohol |

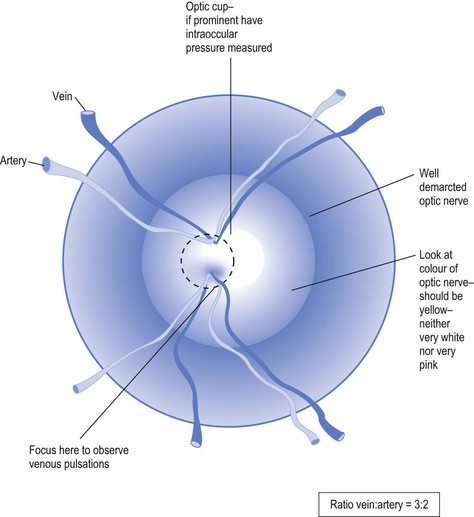

Detailed physical examination is warranted for all headache patients, particularly fundoscopy and searching for focal neurological signs, which should alert the doctor to more serious illness and the need for investigation. It is most important to look for venous pulsations on fundoscopy, which, if present, exclude raised intra-cranial pressure (see Fig 6.2).

Red Flags for the Need for Further Investigation

Some symptoms should alert the doctor to the need for further testing (see Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Need for further investigation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree