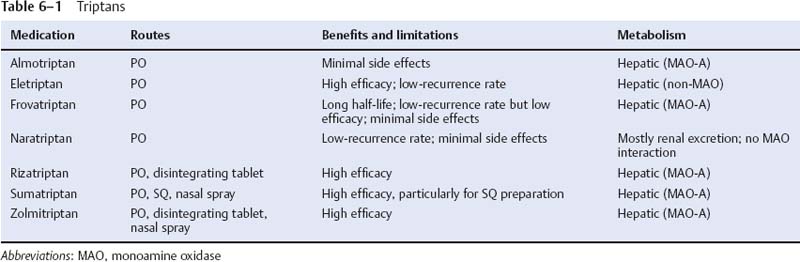

6 Note: Significant diseases are indicated in bold and syndromes in italics. 1. Migraine a. symptoms: attacks last between 4–72 hours (but may be only 1 hour long in children), and typically involve i. at least two of the following: unilateral location; pulsating quality of the pain; severe intensity; aggravation by movement (1) nonpulsatile pain does not exclude the diagnosis of migraine ii. at least one of the following: nausea, photophobia, phonophobia b. subtypes of migraine: patients may have any combination of the various subtypes i. migraine with aura (classic migraine) and without aura (common migraine): phases include (1) prodrome phase (60%): involves psychological, neurological, and/or constitutional symptoms that develop hours to days before the headache onset (a) psychological symptoms include depression, euphoria, and restlessness (b) neurological symptoms include photo/phonophobia and dysphasia (c) constitutional symptoms include anorexia or hunger, sluggishness, fluid retention, and diarrhea/constipation (2) aura phase (in < 30% of all migraine cases): auras evolve gradually, last 4–60 minutes, and involve positive and negative symptoms such as (Box 6.1) In comparison with migranous auras, complex partial seizure auras are shorter (< 5 minutes), produce a change in consciousness, and include automatisms or myoclonic jerks. (a) visual phenomenon: account for 99% of auras; includes the sensation of flashes of light {photopsia}, bilateral scotoma, or a fortification spectrum {teichopsia} (b) complex visual disturbances, including macro/micropsia or metamorphopsia (c) paresthesias and sensory loss (30%); clumsiness (20%); apraxias; speech disturbances; déjà vu/jamais vu; delirium (i) usually these occur in conjunction with a visual aura (3) headache phase: pain can be bilateral in 40%, and consistently is on one side of the head in only 20% of cases (a) 40% of cases involve sharp stabbing pains lasting a few seconds (i.e., idiopathic stabbing headache; see p. 143) (4) postdrome phase: involves impaired concentration, fatigue, and/or irritability lasting for several hours following the headache (1) abdominal migraine—episodes of abdominal pain and nausea often without headache that occur in children with a strong family history of migraine; all other causes of abdominal pain must be excluded prior to establishing the diagnosis iii. complicated migraine/migraine with prolonged aura—migraines in which the aura phenomena persist beyond the duration of headache, or in which stroke-like focal neurological deficits develop (1) migrainous infarction: persistence of the neurological deficits of a complicated migraine for > 1 week or neuroimaging evidence of infarction iv. migraine variants (1) basilar migraine—the migraine aura is followed by any combination of dysarthria, vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss, diplopia, ataxia, bilateral paresthesias or weakness, or confusion; the headache is usually bilateral and located over the occiput (a) hemianopic visual auras may become bilateral, leading to complete vision loss (2) confusional migraine—generally are mild classic migraines that are associated with confusion or agitation; sometimes are triggered by mild head trauma and they rarely recur thereafter (a) usually a disorder of children who have a history of typical migraine; it also is the typical migraine that occurs in patients with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL; see p. 67) (3) ophthalmoplegic migraine—unilateral retroorbital eye pain associated with a cranial nerve palsy (III > IV, VI); episodes occur over a period of days to months before spontaneously resolving; however, they are likely to recur (a) may be related to the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (see p. 34) because the involved nerves contrast enhance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and both disorders respond to steroids (4) hemiplegic migraine—migraine associated with acute-onset weakness and usually confusion, typically lasting < 24 hours; often triggered by mild head trauma (a) subtypes of hemiplegic migraine (i) familial hemiplegic migraine (75% of cases): involves visual phenomena as well as paresthesias (100%) or aphasia (45%) as auras 1. autosomal dominant inheritance with variable penetration, linked to mutation of the P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel gene located on chromosome 19 (Box 6.2) 2. 20% of patients also exhibit slowly progressive nystagmus and ataxia between hemiplegic migraine attacks 3. may develop into a regular migraine syndrome in adulthood 4. sporadic hemiplegic migraine: indistinguishable from familial form (ii) hemiplegic migraine associated with benign familial infantile convulsions (rare): mutation of ATP1A2 sodium-potassium ATPase on chromosome 1 (not the mutation that causes benign familial infantile convulsions without migraine—which is on chromosome 16) (a) migraine during pregnancy does not affect the rate of spontaneous abortion, toxemia, or fetal malformations in comparison with pregnant women without migraine headaches (6) status migrainosus—headache phase that lasts for more than 72 hours with headache-free intervals < 4 hours (not including sleep) c. pathophysiology i. the aura is likely a primary neuronal phenomenon that is triggered by a preceding period of vasoconstriction; reduced blood flow may trigger a brief period of neuronal hyperactivity followed by a prolonged inactivation that spreads outward as a wave moving at 2–6 mm/min across the cortex surface {neuronal spreading depression} ii. the headache is likely due to a combination of (1) extracranial arterial vasodilation: initiated by an unknown trigger, but may be promoted by release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P from unmyelinated fibers of CN V (2) neurogenic inflammation: develops in the region of vasodilation due to plasma protein extravasation as well as the inflammatory effects of neurokinin, CGRP, and substance P released from CN V sensory fibers (3) decreased inhibition of central pain neurotransmission: abnormal function of second-order neurons in the caudal trigeminal nucleus and cervical dorsal horn (“trigeminocervical complex”) may account for headaches that overlap the trigeminal and cervical innervations iii. risk factors for migraine (1) right-to-left cardiac shunt and patent foramen ovale (2) genetic: tumor necrosis factor (TNF) gene polymorphisms; polymorphisms in upstream regulatory region of serotonin transporter (3) psychiatric comorbidities: depression (a) dysthymia and bipolar disorders are associated specifically with migraine with aura iv. epidemiology: age of onset is typically between 10–15 years of age; new-onset migraine is common in women after age 30, but by that age it becomes very rare in men v. triggers include bright light, cigarette smoke, fasting, emotional stress, exercise, poor sleep, alcohol, caffeine, aged cheeses or other foods containing tyramine, chocolate, monosodium glutamate, nitrates, and menstruation d. diagnostic testing i. neuroimaging: not indicated for classic or common migraine unless it is atypical (1) MRI demonstrates small T2 hyperintensities in the subcortical white matter that accumulate over time; occasionally infarction-like changes (i.e., increased diffusion-weighted imaging [DWI] signal) may be seen acutely in cases of complicated migraine (2) EEG can demonstrate any of several focal abnormalities during attacks (e.g., reduced and asymmetric alpha and theta rhythms, poor reactivity), none of which have diagnostic or predictive value e. treatment i. classic and common migraines (1) acute treatment (a) triptans: first-line medication for migraines that are of severe intensity; act as agonists of multiple subtypes of the 5-HT1 receptor both on the vasculature and in brain nociceptive pathways (Table 6–1) (i) most triptans cause vasoconstriction via 5-HT1B receptors, and lipophilic triptans (eletriptan, naratriptan) may also act to reduce the activity of the second-order neurons via 5-HT1B/1D inhibitory receptors (ii) general side effects of triptan agents include chest pain and paresthesias, therefore triptans should not be given to patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease considering the risk of coronary vasospasm (b) nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): may be used as first-line medications for migraines of moderate intensity; act as inhibitors of the constitutive (COX-1) and/or inducible (COX-2) cyclooxygenase enzymes that produce prostaglandins (i) prostaglandins are involved in neurogenic inflammation component of migraine; they also may cause vasodilation and increase the sensitivity of nociceptive pathways (ii) NSAIDs can be used in low-dose combinations or in combined preparations with caffeine or opioids (Box 6.3) (iii) side effects include GI ulceration and renal hypoperfusion causing reduced filtration and renal failure (c) opioids: as effective as triptan agents (d) ergots: generally are considered as rescue medications because of severe side effects (nausea, diarrhea, psychosis, vasoconstriction in the extremities), strict dose limitations, and parenteral administration routes; act on serotonin, adrenergic, and dopaminergic receptors (i) ergotamine: not consistently shown to be better than triptans or NSAIDs (ii) dihydroergotamine: can be administered by nasal spray (e) antiemetics: should be used in conjunction with other treatments when nausea is a significant feature of the migraine (2) prophylactic treatments (a) β blockers (b) antidepressants: amitriptyline, fluoxetine (c) antiepileptics: valproate, gabapentin, topiramate (d) methysergide, which is an ergot that acts on 5-HT2 receptors (i) cannot be used for more than 6 months at a time because of retroperitoneal fibrosis (e) dietary supplements: riboflavin, butterbur extract, coenzyme Q10 (f) relaxation therapy ii. migraine during pregnancy: to avoid harming the fetus, limit treatments to IV fluids, acetaminophen, opioids, and metoclopramide (for nausea) iii. status migrainosus (1) fluid and electrolyte replacement (2) medication detoxification (3) IV therapy (Box 6.4) (a) headache: dihydroergotamine (DHE) ± glucocorticoids, ketorolac (b) nausea: prochlorperazine, metoclopramide (4) establish migraine prophylaxis thereafter 2. Tension-type headache a. symptoms: lacks any prodrome- or aura-like symptoms i. diffuse pain of mild-to-moderate intensity and aching or squeezing quality that is not incapacitating or worsened by head movements; pain often involves the neck and/or jaw (Box 6.5) Distinguish tension-type headache from cervical spine disease by the lack of exacerbation with movements; from temporomandibular joint disease by the lack of jaw clicking or exacerbation with chewing; both disorders will have joint tenderness. (1) the pain often develops a pulsatile quality if it becomes severe (2) occasionally involves mild migrainous symptoms (nausea, photo/phonophobia); more commonly is associated with fatigue or lightheadedness (3) can be triggered by sleep deprivation or emotional stress ii. tenderness of the pericranial muscles and/or temporomandibular joint is an unreliable finding b. pathophysiology i. headaches are associated with a mild diffuse vasoconstriction and low serum magnesium levels (which can cause vasoconstriction); similar abnormalities are also observed in other types of headache as well ii. headache frequency and severity are associated with high levels of anxiety and depression that are not necessarily pathological in severity c. diagnostic testing: the spontaneous activity of the cranial muscles on an EMG is not higher in patients with tension-type headaches than it is in normal controls d. treatment i. regular sleep and exercise; relaxation therapy ii. medical treatments (1) NSAIDs; acetaminophen; caffeine-containing compounds; codeine (a) triptan agents are effective against tension-type headaches only in patients who have coincident migraines (2) anesthetic or botulinum toxin injection into tender cranial muscles 1. Cluster headache a. symptoms: severe throbbing or stabbing pain located around the eye and orbit that may radiate to the jaw, neck, or temporal area; attacks last 45–90 minutes and occur regularly and repetitively over a period of 6–12 weeks before spontaneously remitting (Box 6.6) The Cluster Headache Phenotype i. attacks occur at the same time of day and clusters of attacks occur at the same time of the year, although they become less regular over time (1) headache can be triggered by sleep deprivation, alcohol, organic solvents, or emotional stress ii. patients are agitated and restless during the headache (unlike migraine) iii. pain is strictly unilateral, always occurring on the same side iv. migrainous features (e.g., nausea, phono/photophobia) occur in < 50%; rarely associated with aura v. attacks are triggered by REM sleep, which is shortened by sleep deprivation, therefore patients may avoid sleep vi. attacks are associated with multiple autonomic features: ptosis (70%); conjunctival injection (80%); lacrimation (80%); nasal congestion and rhinorrhea; bradycardia leading to syncope; hypertension b. pathophysiology: likely involves the cavernous segment of the carotid artery and the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the supraoptic region of the hypothalamus because i. attacks are associated with dilation of the ophthalmic artery and cavernous carotid, although this is not specific to cluster headache and can be induced to a lesser degree by pain applied to the CN V-1 region of the face (1) patients exhibit a narrow middle cranial fossa, suggesting venous drainage abnormalities in the cavernous sinus ii. patients exhibit an abnormal circadian rhythm of melatonin release from the pineal gland, which is under the control of the suprachiasmatic nucleus c. epidemiology: typical onset between 25–30 years of age; 5:1 male predominance i. occasional families exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance ii. associated with heavy alcohol and tobacco use d. treatment i. good sleep hygiene with regular hours ii. acute medical treatment (1) oxygen inhalation: 100% oxygen at 7 L/min for 15 minutes via non-rebreather mask gives relief in 70% (2) sumatriptan: effective in 70% when given by the SQ route; not effective as an abortive therapy when given orally (3) dihydroergotamine (DHE) IV (4) intranasal lidocaine, as an adjunct therapy iii. prophylactic medical treatments: to be used during the cluster, then discontinued (1) glucocorticoids: effective at headache prevention but headaches frequently recur during tapering (2) lithium

Headache and Pain Disorders

I. Episodic Headache

A. Episodic Headaches Lasting More than Four Hours

Box 6.1

Box 6.5

B. Episodic Headaches Lasting Less than Four Hours

Box 6.6

Deep nasolabial furrows, peau d’orange skin, telangiectasias {leonine face}

Deep nasolabial furrows, peau d’orange skin, telangiectasias {leonine face}

Masculinized face in women

Masculinized face in women

High-stress (type A) personality

High-stress (type A) personality

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree