Figure 83.1. Initial evaluation of headache in the Emergency Department. Modified from [10].

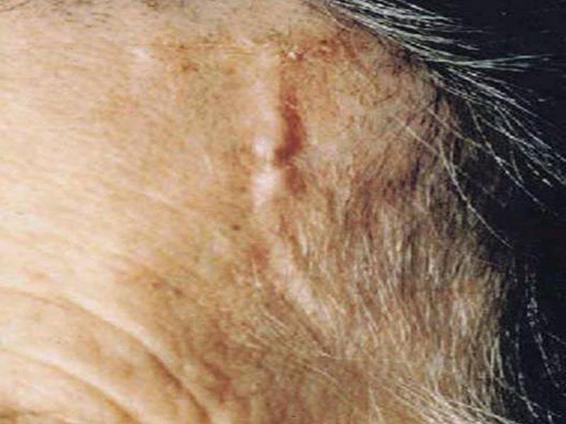

One thing to keep in mind is the patient’s age. Headache that starts after 50 years of age should lead us consider the possibility of temporal arteritis or other secondary aetiologies (Figure 83.2).

Figure 83.2. 67-year-old patient with headache as manifestation of temporal arteritis.

The onset of migraine attacks over age 50 years is very rare because over 90% of patients with migraine suffer their first seizure before the age of 40 years (Table 83.2).

Age at onset | New-onset pain or chronic headache |

Type at onset | Acute, subacute or chronic |

Duration | Temporal pattern and frequency of attacks |

Migraine pain location | Holocranial, facial, occipital |

Accompanying symptoms | Nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, photophobia, aggravation with physical activity, autonomic symptoms |

Other symptoms preceding or accompanying pain | Photopsia, blurred vision, loss of vision |

Pain features | Throbbing, squeezing, burning, stabbing, electric shock |

History of headache | Personal/family, similar/different |

Precipitating and aggravating factors | Alcohol, food, sleep, menstruation |

Treatment | Drugs and dosages previously consumed and therapeutic response |

Table 83.2. Headache history.

83.4 Physical Examination

It is necessary to perform complete neurological examination to look for any type of neurological deficit. Vital functions are also important: temperature, blood pressure, pulse, palpation of head and cranial (temporal and neck) arteries, especially in people over 50 years of age, and examination of the neck and shoulders.

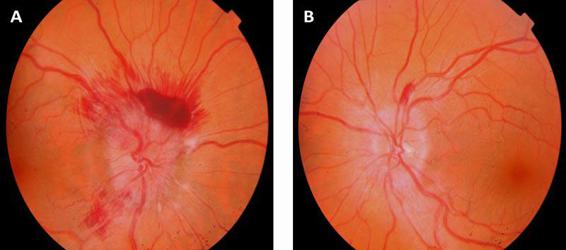

Fundus examination is mandatory to rule out the presence of papilledema, a finding characteristic of increased intracranial pressure caused by tumour or venous thrombosis, signs of subhyaloid bleeding (typically associated with SAH) (Figure 83.3).

Figure 83.3. Fundoscopy with bilateral papilledema. Optic disc swelling in a patient with a brain tumor; hemorrhage is also observed.

It is also important the evaluation of meningeal signs and auscultation of possible cervical-cranial murmurs. The presence of fever or rash should lead the physician to consider a diagnosis of meningitis. Blood pressure >120 mmHg diastolic and/or 200 mmHg systolic may cause headache. A unilateral Horner syndrome without symptoms of cerebral ischemia raises the differential diagnosis of arterial dissection and cluster headache. In cervical arterial dissections, it is relatively common that clinical manifestations are restricted to the presentation of neck, face or head pain with no symptoms associated with cerebral ischemia [14].

History taking and physical examination will help to identify the so-called “flags” criteria (Table 83.3) that suggest a secondary etiology [10-15]. The most important warning signs are pain that starts suddenly after physical exertion or Valsalva manoeuvres and has an explosive onset. Other warning signs are the appearance of headache in patients over 50 years of age, abnormal neurological examination, headache with autonomic symptoms or previous visits to the ED for any other symptoms accompanying the headache.

|

Table 83.3. Alarm signs in headache.

83.5 Risk Stratification. Complementary Studies

An algorithm is structured by assumptions and clinical scenarios that can be a useful tool for ordering and conducting additional tests in the ED.

83.5.1 Analytical Studies

In patients over 50 years of age it is necessary to order a C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) test to rule out temporal arteritis. In those under 50 years, analytical examinations are not usually ordered unless there is suspicion of an infectious process or a history of repeated vomiting and dehydration or suspected electrolyte disturbances (at least electrolyte and renal function tests should be ordered).

83.5.2 Neuroimaging

As shown in the algorithm, the decision to obtain an imaging study is based on the clinical history. There are several clear indications, especially when clinical data or findings on examination suggest a secondary headache when pain characteristics do not conform to a primary headache, and especially in the presence of alarm criteria [15-19].

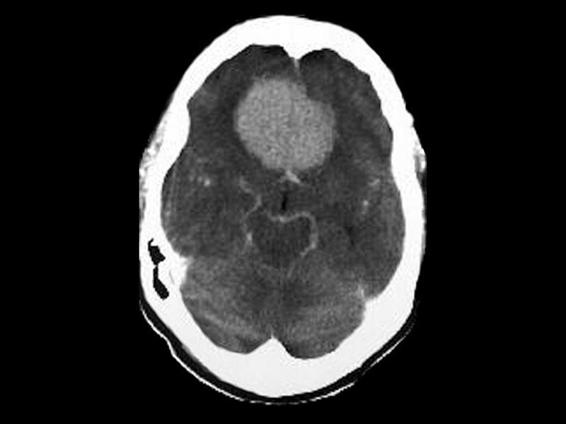

For the assessment of brain parenchyma, the imaging study of choice is an urgent computed tomography (CT), initially without contrast material. On the contrary, if we suspect a Chiari malformation or cavernous sinus pathology, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred. It must be remembered that CT has a lower sensitivity in visualizing lesions of the posterior fossa, sella, cavernous sinus, malformations of the occipito-vertebral hinge (Chiari malformation) or in some specific entities that produce headache secondary to CSF hypotension or cerebral vein thrombosis. The sensitivity and specificity of CT for diagnosing SAH (Figure 83.3) are higher than 98% [20].

Indications for head CT in the ED |

|

Indications for MRI in headache |

|

Table 83.4. Indications for CT and MRI in headache.

83.5.3 Study of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be performed if there is clinical suspicion of CNS infection or SAH with inconclusive CT findings. CSF examination is essential in cases of clinical suspicion of SAH with normal CT. Only exceptionally, when puncture is performed in the early phase of bleeding, the CSF may be normal [21]. It is not uncommon that there is suspicion of a SAH after traumatic lumbar puncture with contaminated blood. In such cases, the doubt can be resolved by performing a lumbar puncture in another interspinal space. It may also be useful to perform a differential count on the number of red blood cells per ml among samples from three different tubes, but xanthochromia has much more value and utility for distinguish between traumatic lumbar puncture or SAH [10]. Xanthochromia should be quantified by spectrophotometry, which can persist in more than 70% of cases after 3 weeks. Xanthochromic liquid can also be seen in the presence of protein levels, hyperbilirubinaemia or hypercarotinaemia. Lysis of erythrocytes with the release of oxyhemoglobin, bilirubin and methemoglobin pigments takes place within a few hours of bleeding. Oxyhemoglobin can be detected within 2 hours and hemoglobin in around 10 hours [13,23-25].

In case of suspected meningitis, encephalitis or SAH with normal CT, lumbar puncture is indicated. In general, brain CT should be done before performing a lumbar puncture because of the risk of herniation (and death) associated with the presence of intracranial space-occupying lesions. Liquoral study is not indicated in patients with a brain abscess.

83.6 Secondary Headaches

The constellation of fever, malaise, headache and purulent rhinorrhoea are characteristic of acute sinusitis. Characteristically, pain intensity increases when bending forward and its location varies depending on the sinus involved, being frontal when the frontal sinus is involved, antral with frontal irradiation in case of the maxillary sinus, retro-orbital and midline in case of haemoptysis, and posterior or anterior in case of sphenoid [26].

A new onset of arterial hypertension can be a cause of headache; and in pregnant women, blood pressure measurement should be performed at the onset of headache.

The presence of an elevated ESR (>50) in patients over 50 years of age should arouse suspicion of temporal arteritis, which is usually present with hemicranial headache with frontotemporal predominance, jaw claudication, constitutional symptoms (asthenia, anorexia, sweating) and visual disturbances that can lead to permanent blindness if corticosteroid therapy is not initiated early. On examination, hardening of the artery, absence of a palpable pulse and pain on palpation can be present. Treatment with prednisone 1 mg/kg/day should be started, with a subsequent tapering down.

Closed-angle glaucoma causes intense pain in the eye and orbit, and vegetative symptoms are often associated with a significant unilateral loss of visual acuity. Physical examination shows red eyes, median pupil unresponsiveness and increased intraocular pressure. If the headache is associated with neck pain, arterial dissection should be included in the differential diagnosis.

There are also headaches induced by certain medications such as nifedipine, nitroglycerin, dipyridamole or sildenafil. Sometimes the headache may be an accompanying symptom or the only symptom of myocardial ischemia. Typically, the headache is triggered by exercise and disappears at rest or after administration of sublingual nitroglycerin [27].

83.7 Headache in Cerebrovascular Disease

Headache occurs at the onset of some nosologic entities of cerebral vascular disease. The one most frequently is associated with headache is SAH (98%), and it may have a prognostic value when there is an arterial aneurysm. It is also frequent in intracerebral hemorrhage and much less often seen in atherothrombotic brain infarction and cardiac embolism.

If the pain is cervical or facial, the underlying process is likely to be dissection pressure. In certain circumstances it is possible that the clinical manifestations are limited to neck, face or head pain, oculosympathetic paralysis associated with ipsilateral Horner syndrome without symptoms of cerebral ischemia, raising the differential diagnosis with cluster headache or a variant migraine.

83.8 Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is due to primary blood extravasation primarily and directly into the subarachnoid space. This distinguishes it from secondary SAH, where the bleeding comes from another location, such as the brain parenchyma or ventricular system. Here we refer to primary SAH. The most common cause (85%) is rupture of an aneurysm, followed by non-aneurysmal perimesencephalic SAH with excellent prognosis (10% of cases), and finally a strange miscellany of other aetiologies (vascular diseases, tumours, etc.) [29].

Although the classic presentation of sudden, intense headache, meningism and focal neurological signs is quite recurrent, it is not unique, and some patients may have other symptoms [30].

Therefore, the degree of suspicion should be high in the presence of an atypical headache (“the worst I have had”, according to patients, very intense or different than usual), especially if associated with any of the following signs and symptoms: loss of consciousness, diplopia, seizures or focal neurological signs.

The existence of a retinal or subhyaloid hemorrhage in this context confirms the diagnostic probability. The most common test is brain CT scan, indicated in an emergency, with a sensitivity of 98% when performed within 12 hours after onset, 93% within 24 hours, and 50% within the week of the episode [30]. There is blood, with a hyperdense area in the subarachnoid space at the convexity or in the basal cisterns. This will allow to identify certain complications (cerebral edema, hydrocephalus, cerebral infarction). If the CT scan is negative, equivocal or the image quality is inadequate, the diagnosis must be confirmed by lumbar puncture. The presence of hemorrhagic CSF is a diagnostic indicator. In case of doubt, the CSF should be centrifuged and examined for signs of subacute hemorrhage, such as xanthochromia and oxyhemoglobin or bilirubin.

Cerebral angiography is still considered the gold standard for diagnosis of cerebral aneurysmal disease. However, this method is invasive and not without neurological and/or non-neurological complications that can be permanent.

Currently, CT angiography or MR angiography are routinely used to search for aneurysms in individuals with a high probability of having them: family members of patients with aneurysms, patients with fibrous dysplasia and polycystic kidney disease. The images are usually of good quality and show the aneurysm size, its neck, and its relationship with the originating and surrounding vessels (Figure 83.4).

Figure 83.4. Brain CT with contrast. Frontal meningioma.

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare entity, clinically characterized by a sudden onset headache followed by vomiting, vision changes, ophthalmoplegia, and decreased level of consciousness [31]. It may be indistinguishable from SAH [32]. The clinical syndrome usually evolves from a few hours to 2 or 3 days. However, stroke may be an incidental finding on tumour resection, subclinical pituitary apoplexy, without prior symptoms.

The incidence varies in different series of surgically treated pituitary adenomas (range, 0.6-9.1%). We believe that MRI, and diffusion and perfusion sequences in particular, add important information for the comprehensive assessment of patients with pituitary apoplexy. MRI not only allows to fully evaluate tumour characteristics and size, but also helps to assess areas of cerebral ischemia and vascular compromission. The most recent application of neuroimaging techniques may be helpful in the correct evaluation of the extent of injury and the decision for early or delayed surgery in these patients.

83.9 Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Headache is the most common symptom (80-90%) and often present in cerebral venous thrombosis [33]. In this condition, early diagnosis is crucial, given the high probability of recovery when anticoagulant treatment is promptly initiated. It has no specific features, and it’s often diffuse with a wide variation in severity.

Around 25% of patients with intracranial hypertension have venous thrombosis. The presentation is usually subacute (days), but it can be acute or chronic. It is a persistent pain that worsens with recumbency and is exacerbated by Valsalva manoeuvres. It’s often associated with other signs of intracranial hypertension, focal deficits or focal seizure syndrome.

Migrainous infarction. This entity is defined as one or more symptoms of migraine aura not fully reversible within 7 days, associated with the presence of infarction on neuroimaging studies. It’s not always easy to determine if it originates from a migraine attack, especially in patients who have associated vascular risk factors. Its diagnosis is necessary to exclude other causes of stroke by appropriate examinations. Although its mechanism is not fully understood, the epidemiological association between the two entities is unquestionable [34].

83.10 Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is characterized by increased intracranial pressure without evidence of intracranial pathology. This is a relatively common disease with an incidence of approximately 1-5/100,000 patients/year. It is much more common in obese women of reproductive age, with a male: female ratio of 15:1. Intracranial pressure is high (>200 mmH2O), as measured by monitoring the epidural or intraventricular pressure or by lumbar puncture. In general, the diagnostic criteria for IIH are based on the symptoms and signs of intracranial hypertension (ICH) and in the absence of laboratory-test abnormalities, including CSF analysis and neuroimaging – preferably magnetic resonance (MR) angiography. Headache is a common symptom of IIH, so that headache associated with IIH is included in the classification of the International Headache Society. However, the characteristics of headache in IIH can be heterogeneous and often present a clinical profile similar to that of some temporary primary headaches. In conclusion, headache associated with IIH presents nonspecific characteristics which can sometimes mimic either primary headache or tension-type headache.

Detailed history taking is essential to search for additional symptoms such as visual disturbances, diplopia, or tinnitus. Fundus examination is mandatory.

The headache must meet one of the following characteristics: daily presentation, a diffuse and/or constant ache (not pulsed) or aggravated by coughing or exertion. It has been observed that about 70% of headache patients have visual disturbances with different characteristics such as blurred vision, decreased visual acuity or visual appearance of scotomas. Less common is the onset of diplopia or cranial nerve VI alterations, which occur in nearly one in three patients with headache. These visual symptoms serve as diagnostic support for suspected ICH [35].

83.11 CSF Hypotension Headache

Intracranial hypotension syndrome is usually secondary to lumbar puncture or trauma. It is characterized by the postural headache associated with low CSF pressure. In healthy humans, the mean CSF pressure is 150 mmH2O (range 65-200 mmH2O) in the decubitolateral position. The symptoms of intracranial hypotension occur at pressures <65 mmH2O.

The brain is held in the cranial cavity and floats on the CSF; the brain’s weight in air is 1500 g but only 50 g in the CSF. Therefore, if the volume of CSF is decreased, the brain descends retrocaudal, carrying with it pain-sensitive structures, particularly cranial nerves V, IX and X, and the first three cervical roots. This downward shift is most evident in the standing position, owing to the effect of gravity, and thus worsens the headache. In intracranial hypotension, headache is a constant symptom rather than hypertension.

According to the criteria of the International Headache Society, intracranial hypotension can be classified into:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree