Chapter 9 Headaches

Secondary Headaches, on the other hand, are often manifestations of an underlying serious, sometimes life-threatening, illness. This category includes temporal arteritis, intracranial mass lesions, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri), meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and postconcussion headaches (see head trauma, Chapter 22). Unlike the diagnosis of primary headaches, the diagnosis of secondary headaches typically rests on their clinical context, physical findings, or laboratory abnormalities.

Primary Headaches

Tension-Type Headache

TTH has traditionally been attributed to contraction of the scalp, neck, and face muscles (Fig. 9-1), as well as emotional “tension.” Fatigue, cervical spondylosis, bright light, loud noise, and, at some level, emotional factors allegedly produce or precipitate TTH. However, because studies have demonstrated that this headache results from neither muscle contractions nor psychological tension, the designation “muscle contraction” or “tension” probably represents a misnomer. The term “tension-type” headache is more appropriate. In fact, many neurologists place this headache at the opposite end of a headache spectrum from migraine, where both result from a common, but unknown, physiological disorder.

FIGURE 9-1 Tension-type headaches produce a bandlike, squeezing, symmetric pressure at the neck, temples, or forehead.

Migraine

Neurologists have said, “Whereas tension type headaches are boring in their sameness, migraine headaches are typically rich in symptoms.” In clinical practice, the core criteria for migraine consist of episodic, disabling headaches associated with nausea and photophobia. The nonheadache symptoms, in fact, often overshadow or replace the headache. The headaches’ qualities – throbbing pain and unilateral location – are typical and included in the IHS criteria (Box 9-1).

Box 9-1

Criteria for Migraine*

At least two of the following characteristics:

The headache is accompanied by at least one of the following symptoms:

Migraine with Aura

Migraine with aura, previously labeled classic migraine, affects only about 20–30% of migraine patients. The aura, which can represent almost any symptom of cortex or brain dysfunction, typically precedes or accompanies the headache (Box 9-2). The headache itself is similar to the headache in migraine without an aura (see later).

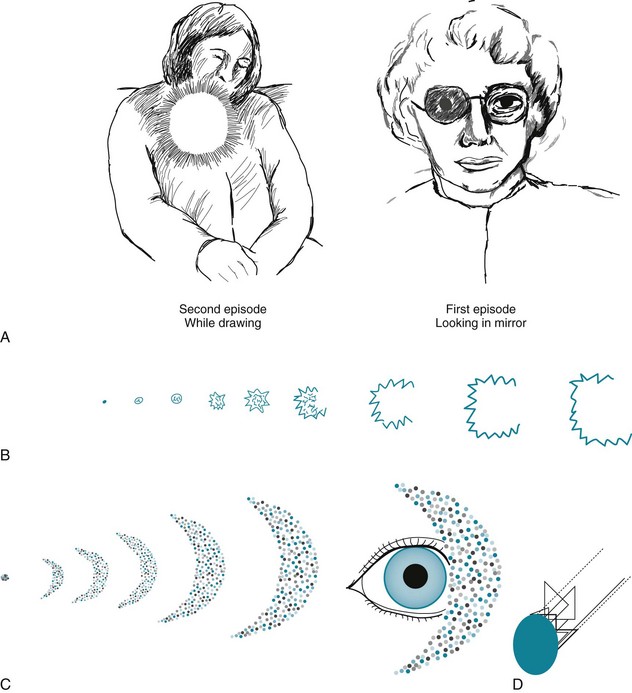

By far the commonest migraine auras are visual hallucinations (see Chapter 12). They usually consist of a graying of a region of the visual field (scotoma) (Fig. 9-2, A), flashing zigzag lines (scintillating or fortification scotomata) (Fig. 9-2, B), crescents of brilliant colors (Fig. 9-2, C), tubular vision, or distortion of objects (metamorphopsia). Unlike visual auras that represent several different neurologic conditions (see Box 12-1), migraine auras most often involve the simultaneous appearance of positive phenomena, such as scintillations, and negative ones, such as opaque areas. Finally, instead of sensory auras, some migraineurs experience premonitory somatic symptoms, such as fatigue, stiff neck, yawning, hunger, and thirst. These patients can frequently predict their impending migraine hours to days before onset.

FIGURE 9-2 A, These drawings by an artist who suffers from migraine show the typical visual obscurations of a scotoma that precedes the headache phase of her migraines. In both cases, she loses a small circular area near the center of vision. As occurs with most migraineurs, she says that, although the aura is only gray and has a simple shape, it mesmerizes her. B, The patient who drew this aura, a scintillating scotoma, wrote, “In the early stages, the area within the lights is somewhat shaded. Later, as the figure widens, you can peer right through the area. Eventually, it gets so wide that it disappears.” This typical scotoma consists of an angular, brightly lit margin and an opaque interior that begins as a star and expands into a crescent. She somehow calculated that it scintillated at 8–12 Hz. Neurologists refer to auras with angular edges as fortification scotomas because of their similarity to ancient military fortresses. C, A 30-year-old woman artist in her first trimester of pregnancy had several migraine headaches that were heralded by this scotoma. Each began as a blue dot and, over 20 minutes, enlarged to a crescent of brightly shimmering, multicolored dots. When the crescent’s intensity peaked, she was so dazzled that she lost her vision and was unable to think clearly. D, Having patients, especially children, draw what they “see” before a headache has great diagnostic value. One adolescent reconstructed this “visual hallucination” using his computer.

Migraine without Aura

Previously labeled common migraine, migraine without aura affects about 75% of migraine patients. In other words, most individuals with migraine do not have an aura. Arising without warning, their headaches are initially throbbing and located predominantly behind a temple (temporal) or around or behind one eye (periorbital or retro-orbital), but usually on only one side of the head (hemicranial) (Fig. 9-3). In the majority of cases, the side of the headache switches within and between attacks. Individual attacks usually occur episodically and last 4–72 hours. Frequent attacks may evolve into a dull, symmetric, and continual pain – chronic daily headache – that mimics TTH.

FIGURE 9-3 Patients with migraine usually have throbbing hemicranial headaches that may either move to the other side of the head or become generalized.

During migraine attacks, patients often have dysphoria and inattentiveness that can mimic depression, complex partial seizures, and other neurologic disturbances (Box 9-3). Most patients withdraw during an attack, but some become feverishly active. Many then tend to drink large quantities of water or crave certain foods or sweets, particularly chocolate. Children often become confused and overactive. After an attack clears, especially when it ends with sleep, migraine sufferers may experience a sense of tranquility or even euphoria.

Box 9-3

Common Neurologic Causes of Transient Mood Disturbance or Altered Mental Status

An additional point of contrast to TTH is that migraine attacks typically begin in the early morning rather than the afternoon. In fact, they often have their onset during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which predominates in the several hours before awakening (see Chapter 17). Sometimes migraines begin exclusively during sleep (nocturnal migraine). No matter when a migraine attack has begun, naturally occurring or medication-induced sleep characteristically cures it.

Psychiatric Comorbidity

TCAs are not only effective for treating migraine comorbid with depression, they are more effective than selective serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs or SNRIs) for treating migraine with or without comorbid depression. SSRIs and SNRIs are less effective than TCAs, and, when administered concurrently with one of the popular anti-migraine serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5HT]) agonists, such as a “triptan” (see later) or dihydroergotamine (DHE), they carry a low but often-cited risk of producing the serotonin syndrome (see Chapter 6).

Other Subtypes of Migraine

Childhood migraine is not simply migraine in “short adults.” Compared to migraine in adults, in childhood migraine the headache is more severe, but briefer (frequently less than 2 hours), and less likely to be unilateral (only one-third of cases). However, as with migraine in adults, the nonheadache components may overshadow the headache. For example, childhood migraine often produces episodes of confusion, incoherence, or agitation. In addition, it frequently leaves children incapacitated by nausea and vomiting. Physicians caring for children with such episodes may consider mitochondrial encephalopathy as an alternative, although rare, diagnosis (see Chapter 6). Pediatric neurologists also consider mitochondrial encephalopathy, along with hemiplegic migraine (see later), in the differential diagnosis of transient hemiparesis in a child with headaches.

Children are particularly susceptible to migraine variants. In basilar-type migraine, the headache is accompanied or even overshadowed by ataxia, vertigo, dysarthria, or diplopia – symptoms that reflect brain dysfunction in the basilar artery distribution (the cerebellum, brainstem, and posterior cerebrum [see Fig. 11-2]). In addition, when basilar migraine impairs the temporal lobes, children as well as adults may experience temporary generalized memory impairment, e.g., transient global amnesia (see Chapter 11). Hemiplegic migraine, another variant, is defined by hemiparesis of various grades often accompanied by hemiparesthesia, aphasia, or other cortical symptoms. All these symptoms usually precede or occur with an otherwise typical migraine headache, but they may also develop without any headache or other migraine symptom. Thus, in evaluating a patient who has had transient hemiparesis, the physician might consider hemiplegic migraine along with transient ischemic attacks, stroke, postictal (Todd’s) hemiparesis, and conversion disorder.

Migraine-Like Conditions: Food-Induced Headaches

On the other hand, people who miss their customary morning coffee typically develop the caffeine withdrawal syndrome that consists of moderate to severe headache often accompanied by anxiety and depression. Although this syndrome is almost synonymous with coffee deprivation, withdrawal of other caffeine-containing beverages or caffeine-containing medications can precipitate it (see Chapter 17). Herein lies a dilemma: sudden withdrawal of caffeine can cause the withdrawal syndrome, but excessive caffeine leads to irritability, palpitations, and gastric acidity. Moreover, excessive caffeine also is a risk factor for transforming migraine to chronic daily headache.

Acute Treatment

Although opioids may suppress headaches, neurologists have remained wary of their leading to drug-seeking behavior (see Chapter 14). In the majority of patients receiving opioid treatment, emergency room visits and hospitalizations decrease, but their headaches and disability persist. Nevertheless, neurologists often prescribe them in limited, controlled doses when vasoactive or serotoninergic medications carry too many risks, such as for pregnant or elderly patients.

Nausea and vomiting not only constitute symptoms of migraine, but they may also be side effects of DHE or another antimigraine medicine. Whatever their cause or severity, nausea and vomiting prevent gastric absorption of orally administered medicines. Many migraine sufferers thus require a parenterally administered antiemetic, such as metoclopramide (Reglan). One caveat remains: dopamine-blocking antiemetics may cause dystonic reactions identical to those induced by dopamine-blocking antipsychotics (see Chapter 18). Thus, neurologists often prophylactically administer diphenhydramine (Benadryl) along with those antiemetics.

Preventive Treatment

TCAs, particularly amitriptyline and nortriptyline, reduce the severity, frequency, and duration of migraine. Apart from their mood-elevating effect, TCAs may ameliorate migraine because they suppress REM sleep, which is the phase when migraine attacks tend to develop. In addition, because TCAs enhance serotonin, they are analgesic (see Chapter 14). As most migraine patients are young and require only small doses of TCAs compared to those used to treat depression, the side effects of TCAs in this situation are rarely a problem. Interestingly, for preventing migraine, SSRIs are ineffective compared to TCAs.

Neurologists often prescribe β-blockers for migraine prophylaxis, as well as for treatment of essential tremor (see Chapter 18). However, they avoid prescribing β-blockers to migraine patients with comorbid depression because of their tendency to precipitate or exacerbate mood disorders.

Chronic Daily Headache

When patients report headaches, each lasting 4 hours or longer, for at least 15 days each month for at least 3 months, neurologists diagnose chronic daily headache. Patients may arrive at this state via several different routes. For years, they may have had migraine or TTH – to the extent that they can be differentiated (Table 9-1) – that transformed from episodes to a daily or nearly every day affliction. Alternatively, individuals, especially children, develop chronic daily headache after a lifetime of having few, if any, headaches, a situation that neurologists label New Daily Persistent Headache (NDPH). Specific conditions, such as a posttraumatic syndrome or psychiatric disturbances, may also lead or contribute to daily headache. Moreover, whatever the route, overuse of analgesics or other medicines often has paved the way to a chronic daily headache.

TABLE 9-1 Comparison of Tension-Type and Migraine Headaches

| Tension-type | Migraine | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Bilateral | Hemicranial* |

| Nature | Dull ache | Throbbing* |

| Severity | Slight–moderate | Moderate–severe |

| Associated symptoms | None | Nausea, hyperacusis, photophobia |

| Behavior | Continues working | Seeks seclusion |

| Effect of alcohol | Reduces headache | Worsens headache |

*In approximately half of patients, at least at onset.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree