MIGRAINE

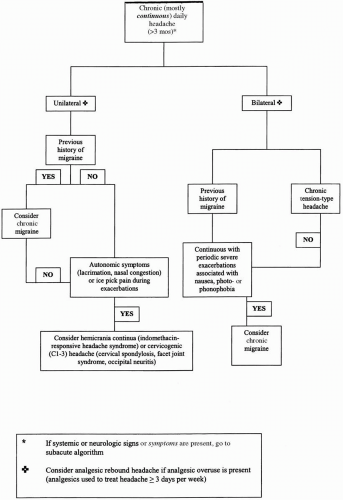

Although migraine attenuates and often disappears with advancing age, approximately one third of individuals with migraine continue to suffer from recurrent attacks into older age. Although rare, some people (2% to 3%) may experience their first migraine attack after the age of 50 years. The prevalence of migraine in the elderly has been estimated to be between 2.9% (

42) and 10.5% (

41). Women continue to be affected more often than men.

The clinical features of the migraine attack may change over time. The pain may more commonly be

holocephalic rather than unilateral (

29). The associated symptoms, mainly photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea and vomiting, occur less commonly in the elderly than in their younger counterparts (

29). The headache may be accompanied by aura, or as frequently recognized in clinical practice, elderly patients may have recurrent attacks of painless aura (

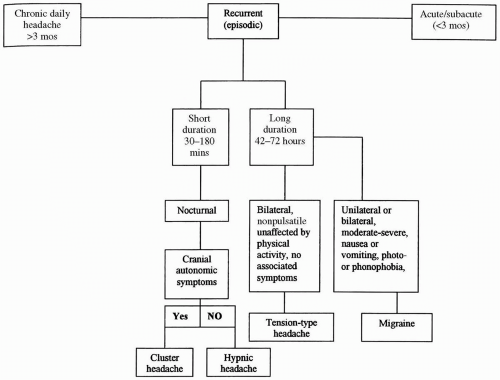

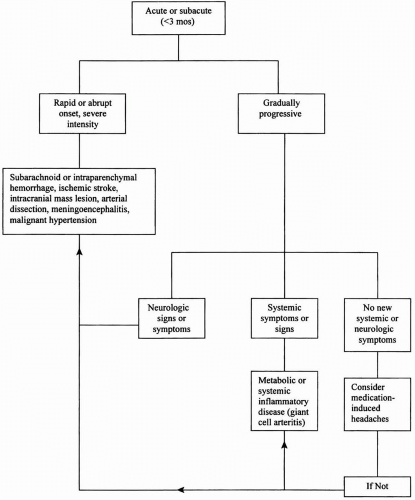

50). Aura without headache, referred to as “late-life migraine accompaniments,” represents reversible focal cortical dysfunction and may take the form of a recurrent hemisensory disturbance (paresthesia) or a scintillating visual scotoma. These episodic focal neurologic disturbances can be easily confused with transient ischemic attacks (TIA). A careful evaluation is important in this setting, including a detailed history of prior migraine attacks, because the incidence and prevalence of cerebrovascular disease increase in the elderly. The key diagnostic features that differentiate late-life migraine accompaniments from TIA are listed in

Table 14-2.

Although the effective therapeutic options for migraine are the same in the elderly, the therapeutic approach to these patients is sometimes a challenge because of coexisting medical illnesses. Managing the older patient with migraine requires a thorough familiarity with the individual’s health status and a practical knowledge of pharmacology (

34). Vascular disease, for example, precludes the use of migrainespecific medications such as ergotamine derivatives and triptans. Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are best avoided in patients with depression or congestive heart failure, whereas prostatism, glaucoma, heart failure, or arrhythmias may preclude the use of tricyclic antidepressants. Moreover, even when these contraindications do not exist, the elderly are more likely to experience more side effects from certain medications, such as sedation and confusion with tricyclics or impaired renal function with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because of diminished renal function and creatinine clearance (

34).

In addition, medications used for certain medical disorders can exacerbate migraine in this population. For example, the use of vasodilating antihypertensive medications (e.g., nifedipine or methyldopa) can worsen migraine or lead to an increase in the frequency of attacks. Similarly, when used for ischemic heart disease, nitrates can precipitate an attack of migraine or cluster headache in those who are predisposed.

TENSION-TYPE HEADACHE

TTH is a “featureless headache.” It is a dull, bilateral, or diffuse headache, often described as a pressure or squeezing sensation of mild to moderate intensity. It has no accompanying migraine features (e.g., nausea, emesis, photophobia, phonophobia), and the pain is not worsened with movement and does not prohibit activity. No cranial autonomic symptoms are noted. When presenting as a new headache, especially in patients over the age of 40 years, it should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion because it is the headache phenotype most frequently mimicked by brain tumors and other organic causes of headache. The exact prevalence of TTH in the elderly is difficult to assess because of various definitions used across studies and the propensity for organic disease to masquerade as TTH in this age group. However, estimates range from 18% (

45) to 52% (

41). Although most elderly people have had TTH since youth or middle age, about 10% develop TTH after the age of 50 years. Again, a careful search for organic disease is imperative in this particular group because many underlying metabolic, systemic, and psychiatric (depression) disorders and structural intracranial disease present with

ill-defined, nonpulsatile, bilateral headaches that could easily be mistaken for TTH.

The approach to treatment should involve nonpharmacologic treatment strategies as well as the judicious use of NSAIDs, analgesics, and tricyclic antidepressants for prophylaxis.

CLUSTER HEADACHE

Cluster headache is one of the most distinctive of the primary headaches, with an unmistakable attack profile. The pain is so excruciatingly intense that it has been termed the “suicide headache.” It is often maximal in the orbital region and peaks in intensity within 5 minutes. It can occur during the day or, characteristically, awaken a patient out of a sound sleep. The pain lasts between 15 minutes and 2 hours, but the average duration is 60 minutes if untreated. One or more cranial autonomic features, such as lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, ptosis, meiosis, and conjunctival injection, are seen in more than 97% of patients. Rarely, cluster headache can begin as late as the eighth decade, although this type of headache in elderly individuals invariably will have started at a younger age. The average age of onset is approximately 28 years, and men are affected four times more often than women (

13). Although cluster headache is uncommon in random surveys of the healthy elderly, it accounts for up to 4% of elderly patients presenting to headache clinics (

42). New-onset cluster headache has been reported in the elderly (

47), with the oldest age of onset being a 91-year-old woman (

40).

As with migraine and TTH, the treatment of cluster headache in the elderly is frequently complicated by the presence of coexisting medical disorders. Subcutaneous sumatriptan, the most effective medication for the acute treatment of cluster headache, must be used with caution in those with cardiovascular risk factors, especially because cluster headache occurs more commonly in men, the majority of whom are chronic smokers. For patients with coexistent cardiovascular disease or significant risk factors, oxygen inhalation is the safest and most effective acute agent. Verapamil, usually combined with a short course of corticosteroids, is often highly effective in terminating a cluster period or reducing the frequency and intensity of attacks during this period (

13).

HYPNIC HEADACHE

Hypnic headache, a primary headache disorder that primarily affects elderly individuals, occurs exclusively during sleep (

12,

37). The mean age of onset is approximately 60 years, and women are more often

affected than men. The headache typically awakens the individual from sleep often at or near the same time each night, prompting the term “alarm-clock” headache. The headache is moderate to severe in intensity and often bilateral and squeezing, although the pain can be unilateral in up to one third of patients. Generally, no associated “migrainous” symptoms (e.g., nausea, emesis, photophobia, phonophobia) or cranial autonomic symptoms (e.g., lacrimation, rhinorrhea), as seen with cluster headache, occur. The pain usually lasts 30 to 60 minutes, although attacks can last several hours. Remaining in a supine position often exacerbates the pain; therefore, most individuals will report needing to rise from bed for relief. Nocturnal attacks often occur more than four nights per week, and some individuals may have several attacks through the night. In some patients, an attack can occur during a daytime nap.

Recently, a case of symptomatic hypnic headache has been reported (

36). This underscores the need to proceed with appropriate neuroimaging to exclude a secondary headache disorder.

Lithium carbonate is an effective treatment, but the side effects in this age group sometimes preclude its long-term use (

12,

37). Caffeine, either by tablet or as a cup of coffee before bedtime, can be effective for some patients (

12). Other medications reported to be effective for prophylaxis include flunarizine (

33), indomethacin (

11), melatonin (

15), topiramate (

20), and pregabalin (

48).