Headache, a frequently occurring disorder in children and adolescents, causes considerable discomfort and leads to time lost from school and work. It affects the family as well as afflicted children and adolescents. The majority of headaches in children and adolescents are not associated with structural or organic disease. In evaluating and treating headaches in children and adolescents, physicians must consider physical, psychological, and socioeconomic factors in determining the correct diagnosis and selecting optimal therapy. A thorough history coupled with complete general physical and neurological examinations, as well as the use of selected laboratory tests, will guide the clinician to the correct diagnosis. Treatment is most effective when both the specific headache type and its etiology are known (

1).

Physicians caring for headache patients of any age understand that headache may be a symptom of a medical disorder, a primary headache disorder without a medical cause, or a psychiatric disorder. In particular, they recognize that headaches may be one component of a psychiatric disorder, may be associated with psychiatric disorders, may be precipitated by psychological difficulties, or may be unrelated to the patient’s emotional problems. Mental health workers have special skills that may be beneficial in both the evaluation and the treatment of headache syndromes in children and adolescents (

2).

This chapter reviews the common types of headache seen in children and adolescents and provides a systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment. It also discusses the psychiatric, psychosocial, lifestyle, and socioeconomic and family factors that play a role in the pathogenesis and treatment.

History

Hippocrates described migraine 25 centuries ago (

3). Years later Galen coined the term

hemicrania (

3). William Henry Day, a British pediatrician in his book,

Essays on Diseases in Children, recognized that nonorganic, nonvascular headaches were the most common type of headache in children. He stated, “Headaches in the young are for the most part due to bad arrangements in their lives” (

4). A milestone in the study of pediatric headache occurred in 1962 when Bille (

5) published his data on the frequency of headache in 9,000 school children. More recently, four textbooks and two practice parameters that focus on pediatric headache have been published (

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11).

Epidemiology

See references

12 and

13 for a discussion of epidemiology. In the Bille treatise, the entire school age population of Uppsala, Sweden, between the ages of 7 and 15 years of age was

studied. It was noted that by 7 years of age 2.5 % of children had frequent tension headaches, 1.4% had migraine, and 35% had infrequent headaches of other varieties. By age 15, 15.5% had frequent tension headaches, 5.3% had migraine, and 54% had frequent headaches of other varieties (

5). The frequency of migraines in prepubertal boys is higher than in prepubertal girls. At puberty the frequency of migraine is higher in girls. In adults, the frequency of all types of headaches, except cluster headache, is higher in women. The frequency of chronic migraine, mixed migraine, and tension headache is lowest in children younger than 7 years and increases between the ages of 7 and 12. In children 12 to 18 years of age, chronic headaches are more common than acute episodic migraine alone. The overall prevalence of headache increases quite strikingly in the period from preschool to adolescence. Overall, headache prevalence by 7 years of age is 37% to 51% and at ages 7 to 15 years, from 57% to 82%. The incidence of migraine with

aura in boys is 6 per 1,000 and peaks at 5 to 6 years of age. The incidence of migraine without

aura in boys is 10 per 1,000 and peaks at 10 to 11 years of age. The incidence of migraine with

aura in girls is 14 per 1,000 and peaks at 12 to 13 years of age. The incidence of migraine without

aura in girls is 18 per 1,000 and peaks at 14 to 17 years of age.

Epidemiological studies in adults show an association between migraine and anxiety disorders (

14,

15). Most studies have found a bidirectional relationship, with migraine predicting subsequent depression and depression predicting migraine. The relationship between anxiety disorders and migraine is also bidirectional.

In addition, childhood- or adolescent-onset headaches are associated with depression and anxiety (

15). The weight of the evidence suggests that pediatric migraine is associated with depression and that the association is stronger in girls and adolescents. Similarly, the association between pediatric migraine and anxiety seems to be stronger for girls than boys. In boys, there is also some evidence of an association between headaches and disruptive behavior disorders. Although studies are fewer, there appears to be a relationship between chronic daily headaches and depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidal ideation (

16).

Classification

The “Second Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders” (ICHD), published in 2004, bases its classification on the presumed abnormality, its origin, and its pathophysiology or symptom complex. The criteria are neither specific nor sensitive to the issues of headache in children and adolescents (

17).

Authors have reviewed the initial classification and suggested modifications for the pediatric population (

18). For example, the duration of headaches in children is shorter than in adults, and many young children have bilateral as opposed to unilateral headaches.

Headache can also be classified as primary or secondary. Primary headaches, such as migraine and cluster, have no underlying pathology; however, migraines frequently have a genetic basis. Secondary headaches are those due to an underlying pathological condition, such as a tumor, hemorrhage, hypertension, collagen vascular disorders, infection,

hydrocephalus, trauma, or toxin.

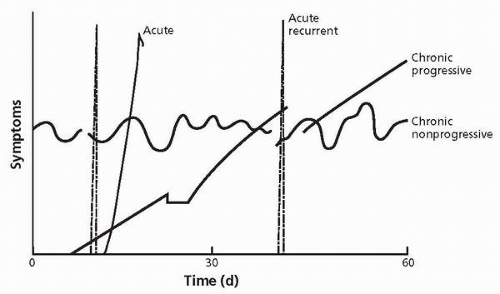

In addition to the ICHD, it is helpful to classify headaches using the temporal pattern of the headache plotted against its severity (

19). Four patterns can be identified:

1. Acute

2. Acute recurrent (migraine)

3. Chronic progressive (organic)

4. Chronic nonprogressive (

Fig. 7.1), which includes tension-type headaches, chronic daily headaches, mixed migraine, tension headache, and chronic or

transformed migraine

An acute headache is a single event with no history of a previous similar event. Most of these headaches are seen in the primary care setting. Many are associated with febrile illness or minor trauma. If the acute headache is associated with neurological symptoms or signs, an organic process should be suspected. The differential diagnosis of an acute headache, both generalized and localized, involves a wide variety of disorders (

Table 7.1).

Acute headaches can also be seen in the setting of an emergency room. A summary of four studies indicates that the overwhelming majority of children and adolescents presenting to the emergency room with acute headache do not have serious neurological problems but rather migraine, tension-type headache, non-central nervous system (CNS) infection, or posttraumatic headache (

Table 7.2) (

20).

Acute recurrent headaches are usually migraines. If a similar headache has occurred and resolved several times, migraine is the most likely diagnosis. These headaches are painful but not life threatening. However, if the migraine is associated with neurological

symptoms or signs, other potentially life-threatening causes must be considered (

Table 7.3).

As time passes, symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, progressive neurological disease, or focal or generalized neurological signs sometimes accompany the headache. As with acute recurrent headaches, if a progressive headache is associated with neurological symptoms or signs, potentially life-threatening causes must be considered (

Table 7.4). Although most evolve over time, they may present precipitously.

Chronic nonprogressive headaches are also known as tension-type headaches, muscle contraction headaches, mixed headaches, chronic migraine,

transformed migraine, or comorbid headache. The episodic variety occurs fewer than 10 to 15 days per month and children with it are seldom seen in consultation. If, however, the headaches occur more than 10 to 15 days per month, interfere with normal school and family function, or are associated with medication overuse or excessive school absences, then the patient needs to be evaluated. These headaches are not associated with symptoms of increased intracranial pressure or progressive neurologic disease. They often combine features of tension type and migraine. Examinations of patients are normal both during the headache and between headaches. Laboratory studies are generally nonrevealing. These headaches, although not life-threatening, are among the most refractory to treatment. They are often associated with psychological factors, lifestyle issues, overuse of medications, excessive school absences, and low socioeconomic status.

These headaches are also often associated with other somatic complaints, such as recurrent abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pains, fatigue, and dizziness, and may be the early symptoms of anxiety or depression. Pain symptoms are part of the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnostic criteria for separation anxiety disorder, pain disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and somatization disorder. Although not part of the diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode, headaches and other somatic complaints are frequent presenting symptoms of mood disturbance in childhood.

Pathophysiology

Both extracranial and intracranial structures may be sensitive to pain (

21,

22). Pain from extracranial and intracranial structures from the front half of the skull are mediated via the

fifth cranial nerve. Pain from the occipital half of the skull is mediated via the upper cervical nerves. Inflammation, irritation, displacement, traction, dilation, and invasion of any of these pain sensitive structures will cause headache or head pain. However, the child’s age, illness, fatigue, nutrition, psychological factors, ethnic factors, and previous experience with pain will modify the child’s perception of headache and other pain. The severity of the pain should

not be taken as an absolute indicator of the severity of the underlying process or even its organicity.

Biochemical, neurotransmitter, and regional cerebral blood flow studies have produced the trigeminal vascular hypothesis for the pathogenesis of migraine. This hypothesis considers migraine an inherited sensitivity of the trigeminal vascular system (

21). Cortical, thalamic, or hypothalamic mechanisms initiate an attack in individuals who are genetically predisposed to be sensitive to internal or external stimuli. Impulses spread to the cranial vasculature and brainstem nuclei and produce a cascade of neurogenic inflammation and secondary vascular reactivity. Vascular peptides are released and activate endothelial cells, mast cells, and platelets, which then increase extracellular amines, peptides, and other metabolites that result in sterile inflammation and pain transmitted centrally via the trigeminal nerve.

Spreading depression begins in the visual cortex and propagates to the periphery at a speed of 3mm per minute. The human

aura propagates in a similar fashion (

22).

Improved understanding of the relationship of headaches to serotonin has resulted in both improved acute and chronic treatments. Serotonin receptors are implicated in constriction of cerebral blood vessels. The antimigraine agents dihydroxy-ergotamine and the

triptans have potent activity at the 5HT1D and 5HT1B receptor sites. A number of potent 5HT1 antagonists, such as methysergide, cyproheptadine, amitriptyline, and verapamil, are effective in preventing migraine attacks. In addition, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) that involve both calcium and sodium channels, such as sodium valproate, topiramate, and gabapentin, are useful in prevention.

The reasons for the association between headaches and psychopathology remain unclear, but there are suggestions that dysregulation of the serotonergic and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic systems may be involved in migraine, depression, and anxiety. Neural pathways involving the periaqueductal gray have been implicated in pain regulation and receive input from limbic system pathways involved in emotion.

Evaluation

Evaluation of the child or adolescent with headaches is the key to appropriate treatment (

10,

24). A properly obtained history is necessary to differentiate the various headache types, their etiologies, and their

comorbidity. Physicians should conduct a private interview with adolescents regarding physical abuse, sexual activity, sexual abuse, substance abuse, and other personal aspects of their medical, social, and academic history.

The history begins with details of pregnancy, labor, delivery, early childhood development, school function, previous medical problems, previous medications for headache, and the use of medication on a chronic basis for other disorders. Physicians should inquire about over-the-counter as well as prescription medicines. Both the patient and the parent should be questioned regarding anxiety, tension, nervousness, depression, inappropriate behavior, sleep schedules, and school function and absences. The family history should detail any family members with migraine, tension-type headaches, and psychological or psychiatric disorders. A second set of questions deals with the headache itself (

Table 7.5).

The third set of questions should deal with symptoms, in addition to headache, of increased intracranial pressure or progressive neurological disease, including,

ataxia, other balance problems, excessive lethargy, seizures or loss of consciousness, visual disturbances, focal or generalized weakness, vertigo or dizziness, personality change, loss of abilities, or change in school performance. Physicians should consider potentially ominous etiologies if children have had a change in a previous headache pattern, the severity of the headaches has increased dramatically, or the headache pain awakens them from sleep.

A general physical examination is necessary. If the child psychiatrist does not perform this general examination, the patient should be referred to a primary care physician. Careful attention should be paid to the vital signs, and any abnormality of blood pressure or temperature should be recorded. The skin must be closely examined for striae, rashes, and bruising

or neurocutaneous abnormalities, such as café-au-lait spots. Looking for signs of sinusitis and temporal mandibular joint dysfunction, the physician should palpate and auscultate the skull, neck, and sinuses. In the overwhelming majority of patients with tension-type headaches and migraine, the general physical examination reveals no abnormality.

If the child psychiatrist does not perform a neurological examination, the patient should be referred to a pediatric neurologist. The pediatric neurologist must pay special attention to any signs of trauma or nuchal

rigidity. The head circumference, optic fundi, eye movements, strength, reflexes, and coordination should be recorded. Children and adolescents with tension headaches and migraine should always have a normal neurological as well as a general physical examination.