CHAPTER 4 Health and health psychology

The material in this chapter will help you to:

Introduction

Psychological theories offer complementary and, at times, competing views of human behaviour that reflect different assumptions about the nature of individuals and how they should be studied. These varying theoretical perspectives include bioscience, psychoanalytic, behaviourist (or learning), cognitive and humanistic theories. These explanations are described in detail in Chapter 1 and underpin the approaches used in health psychology. You will discover that each theoretical position offers a different perspective on human behaviour and each may provide useful explanations in specific situations. Nevertheless, none provide a universal explanation of behaviour that is applicable to all people in all situations.

What is health?

Health is a construct that can be defined in both broad and narrow terms. Narrow interpretations are provided by the biomedical model, which emphasises the presence or absence of disease, pathogens and/or symptoms. A broader interpretation is provided by the biopsychosocial approach that posits that health is influenced by a complex interaction of biological, psychological and social factors. See Table 4.1 for sociological, psychological and biomedical factors that influence health.

Table 4.1 Models of health and their influences

| MODELS OF HEALTH | ||

|---|---|---|

| Biomedical | Psychological | Sociological |

Additionally, health can be examined both objectively and subjectively. Objective measures such as an X-ray or scan can indicate health or illness, while an individual’s subjective interpretation will report whether he or she feels healthy or ill – but there may be no correlation between the two. For example, a person may report feeing healthy but have dangerously high blood pressure, or another person may report pain for which physical pathology cannot be identified. Therefore, given the range of criteria and the different perceptions that can influence a definition of health, it is not surprising that many interpretations exist and that debate surrounds an agreed definition of the concept (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2007, Jormfeldt et al 2007).

Furthermore, health can have different meanings for the general public or lay people than it does for health professionals. Three consistent themes arise in research into lay people’s understanding of the concept of health. They are: health is not being ill; health is a prerequisite for life’s functions; and health involves both physical and mental wellbeing (Baum 2008 p 7). Baum suggests that these lay definitions have more in common with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of health than biomedical interpretations do.

Biomedical model

However, by the latter half of the 20th century it became apparent that the treatment era of the previous decades did not live up to the expectations of the scientific or wider community. In Western countries, for example, diseases related to lifestyle now pose a greater threat to health than that of infectious diseases. Also, with regard to the treatment of infectious diseases, some bacterial strains have developed resistance to antibiotics and for most cancers neither a cure, nor preventive vaccination has been discovered. In the main, cancer prevention and chronic illness management strategies are related to lifestyle and the environment, such as cease cigarette smoking, use sun protection, be physically active, eat a healthy diet and maintain weight within the healthy range.

In the mental illness field the unwanted side effects of antipsychotic drugs are often problematic and can contribute to non-adherence to treatment, for example, the rapid and sustained weight gain and iatrogenic diabetes mellitus experienced by some patients taking atypical antipsychotic medication to treat schizophrenia (Bai et al 2006). Such consequences of treatment present a challenge to both patients and health professionals with regard to the relative cost–benefit of the treatment. For patients, the unwanted social and health consequences may interfere with adherence to the recommended treatment. For the health professional, there is the ethical dilemma of encouraging adherence to a treatment for one health condition such as schizophrenia that carries a high risk that the patient will develop another serious health condition such as diabetes mellitus.

CHALLENGES TO AN EXCLUSIVE BIOMEDICAL APPROACH

Initially, the biomedical model held great promise to improve the health of individuals and communities. Scientific research in the 20th century led to the discovery of medications that could cure, or eliminate, many diseases. Sulphur drugs – developed in the 1930s – and, later, other antibiotics revolutionised the treatment of infection. In the mental health field the first antipsychotic medication (chlorpromazine) was introduced in 1950. At the time it was lauded as a breakthrough in the treatment of schizophrenia because of its ability to reduce disruptive behaviour (Meadows at al 2007). Patients who would have been in straitjackets and lived out their life in a mental institution now were able to be discharged and returned to live in the community.

However, by the middle of the 20th century concerns were mounting regarding the cost escalation of scientific, technological medicine and worldwide there was recognition of the need for sustainable environments. It was also evident, particularly in Western countries, that the diseases that threatened communities were no longer infectious and acute but were chronic and related to lifestyle. For example, the health conditions that now carry the greatest burden of disease are mental illness, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, substance abuse and interpersonal violence (Marmot & Wilkinson 2006).

Challenges to the biomedical model as the exclusive framework for understanding health and to structure the delivery of healthcare services began to emerge from the middle of the 20th century, the major criticism being that an exclusive biomedical approach fails to take into account the contribution of broader psychological, sociological, political, economic and environmental factors that influence health and illness. A further criticism of an exclusive biomedical approach is that health resources are directed to costly curative services rather than to health promotion or illness prevention. Baum argues that ‘there needs to be more research on the ways in which social and economic factors affect health and what social, educational, housing and health interventions most improve health and health equity’ (Baum 2008 p 145).

And finally, while 86% of increased longevity in Western countries can be attributed to the public health initiatives of the 19th and early 20th century (i.e. clean water, suitable housing and sanitation) only 4% of increased longevity can be attributed to sophisticated medical interventions of the 20th century (New Internationalist 2001). Given that up to 75% of governments’ health budgets are allocated to acute hospital services there seems to be a disparity between resource expenditure and health outcomes (Government of South Australia 2003). Hence, the question arises: Is the allocation of the bulk of health funding to acute treatment services the most effective allocation of financial resources to achieve the best health outcomes for individuals and communities?

Biopsychosocial model

The notion of an alternative to the biomedical model was first proposed by Engel (1977) and quickly gained momentum among health professionals and policymakers. The biopsychosocial model is holistic in approach and thereby avoids the mind–body split inherent in the biomedical model. A further outcome of this approach is the recognition of the contribution made by allied health professionals to healthcare and the emergence of the multidisciplinary team as a mechanism for providing health services.

HEALTH PRIORITIES

Australia’s National Health Priority Areas (Australian Government DH&A 2005) are health issues identified by the federal Department of Health and Ageing for focused attention because they contribute significantly to the burden of illness and injury in Australia. The seven priority areas are: cancer control; injury prevention and control; cardiovascular health; diabetes mellitus; mental health; asthma; and arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions – all of which have complex aetiology including lifestyle, biological, psychological and social factors. In addressing these health problems the holistic nature of the biopsychosocial model offers greater opportunity to improve health outcomes than a biomedical approach alone because the biopsychosocial approach addresses more than just the symptoms of the condition.

Nevertheless, despite the intrinsic appeal of the biopsychosocial model some critics argue that, generally, social issues are not sufficiently addressed in practice (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006 p 12). Utilising another approach – primary health care/new public health that operates from a biopsychosocial framework and has a strong emphasis on social and political issues that impact health – is a way to overcome this shortcoming.

Primary health care/new public health

Worldwide policymakers, health professionals and communities were increasingly looking beyond the biomedical model for answers to health problems (Baum 2005). In 1981 LaLonde, the Canadian Minister of National Health and Welfare, described four general determinants of health that he called human biology, environment, lifestyle and healthcare organisation. Supporting a shift from a biomedical approach to a broader approach acknowledging biopsychosocial factors Lalonde stated:

In 1986, eight years after the Alma-Ata declaration, the first WHO International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa, Canada. Conference participants developed an action framework of five strategies (the Ottawa Charter) to achieve Health for All. These five strategies have become the cornerstone of the primary health care/new public health movement.

Table 4.2 Actions of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

| OTTAWA CHARTER STRATEGY | ACTION |

|---|---|

| Build healthy public policy | Direct policymakers to be aware of the health consequences of their decisions and to develop socially responsible policy |

| Create supportive environments | Generate living and working conditions that are safe, stimulating, satisfying and enjoyable |

| Strengthen community action | Empower communities, enable ownership and control of their own endeavours and destinies |

| Develop personal skills | Support personal and social development through providing information, education for health and enhancing life skills |

| Reorient health services | Share responsibility for health promotion in health services amongst individuals, community groups, health professionals health service institutions and government |

Health of Australians and New Zealanders

When compared with other countries in the world, the health of Australians and New Zealanders ranks highly. It is rated among the top 10 developed countries in the world across a range of significant indicators. Life expectancy is ranked among that of the top nations in the world. See Table 4.3 for life expectancies for selected countries.

Table 4.3 Life expectancy in selected countries

| SELECTED COUNTRIES | LIFE EXPECTANCY AT BIRTH |

|---|---|

| Singapore | 81.71 |

| Hong Kong | 81.59 |

| Japan | 81.25 |

| Australia | 80.5 |

| Indigenous Australians | 62.0 |

| Norway | 79.54 |

| New Zealand | 78.81 |

| Māori | 71.1 |

| United Kingdom | 78.54 |

| United States | 77.85 |

| China | 72.58 |

| Indonesia | 69.87 |

| Papua New Guinea | 65.28 |

| India | 64.71 |

| Botswana | 33.74 |

Source AIHW 2007, Nationmaster 2007, NZ Ministry of Social Development 2004

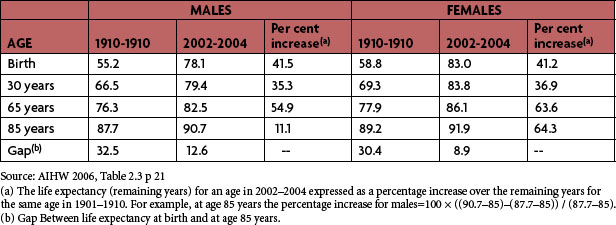

In addition, Australians born in the 21st century can expect to live 20–25 years longer than their ancestors born at the commencement of the 20th century. That is, a male born in 1901 had a life expectancy of 55.2 years, whereas a male born in 2002 has a life expectancy of 78.1 years. See Table 4.4.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree