OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Define the term health-care disparities.

Describe the patient and provider factors that influence access to and the use of health-care services.

Review the characteristics of patients who are at increased risk for health-care disparities.

Identify actions health professionals can take to promote equity in health care.

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter defined health disparities as systematic, yet potentially modifiable, differences in health between more and less privileged social groups. This chapter focuses more narrowly on health-care disparities. After defining this term, the factors that contribute to health-care disparities, the patients affected by these inequities in access to and quality of care, and strategies to eliminate health-care disparities are discussed focusing on these issues in the US health-care setting.

QUALITY OF CARE AND HEALTH-CARE DISPARITIES

The Institute of Medicine has defined quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1 Quality can be impaired in different ways, such as overuse, underuse, and misuse. There are major deficiencies on all of these accounts in the quality of care provided by the US health-care system. For example, there are major deficiencies in the quality of care provided to patients with common chronic diseases: two-thirds of patients with high blood pressure are inadequately treated; the majority of patients with diabetes have glycohemoglobin (A1C) levels >7%; and half of the patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure are readmitted within 90 days of discharge.

Furthermore, many studies have shown that social status can contribute to the quality of care a patient receives. Social status may alter health-care professionals’ perceptions of patients’ needs or the way in which patients interact with health services and this in turn may influence the quality of care that is received. In the United States, for example, patients from racial and ethnic minority groups as compared with white patients experience more frequent barriers to care, more limited treatment options when presenting for care, and greater deficits in the quality of care. Such health-care disparities are seen in association with measures of social status throughout the world. For example, in the United Kingdom, quality of care for patients with diabetes is positively associated with income.2

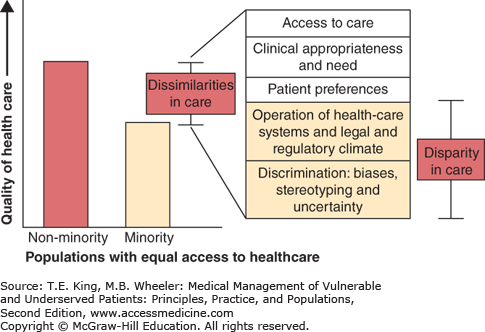

These health-care inequities reflect systematic differences in access to or quality of care between more and less privileged groups that cannot be explained by the differences in the need for care or preference for care among the individuals in these groups (Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1.

Model of health-care disparities. The Gomes and McGuire model views health-care disparities as resulting from characteristics of the health-care system, the society’s legal and regulatory climate, discrimination, bias, stereotyping, and uncertainty. Not all dissimilarities in care are considered a disparity in care. (Adapted from Gomes C, McGuire T. Identifying the sources of racial and ethnic disparities in health-care use. Boston, MA: Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 2001. Cited in Smedley BA, Stith A, Nelson A, eds. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; LaVeist TA, Isaac L. Examples of Racial Disparities in Health Care. Baltimore, MD, 2005.)

MEASURES OF QUALITY: PROCESSES OR OUTCOMES OF CARE

William Mason and Peter Dixon are admitted to the same hospital on the same day with the same diagnosis: ST wave elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Mr. Mason, a white business executive, is promptly rushed to the cardiac catheterization suite where he receives coronary angioplasty and stenting. He is discharged home on aspirin, clopidogrel, a statin, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Three months later, he is able to garden without experiencing angina. Mr. Dixon, an African American who is an intermittently employed construction worker, is admitted to the coronary care unit but does not receive a coronary arteriogram during his hospital stay. He is discharged home on a statin and calcium channel blocker. Two weeks later, he is readmitted with unstable angina.

Applying a quality-of-care framework developed by Donabedian, health-care disparities can be observed to occur in the processes or outcomes of care.3 Processes of care are the actions health-care providers take to diagnose, treat, and manage patients’ health-care needs. Health outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, are, in part, consequences of these health-care actions.

Mr. Mason had a process of care that was more consistent with evidence-based guidelines than the care received by Mr. Dixon. The inferior process of care received by Mr. Dixon contributed to him having a worse clinical outcome (recurrence of symptomatic coronary heart disease) than Mr. Mason. Of particular concern are the types of health-care disparities illustrated in this case that contribute to inequities in health outcomes (health disparities).

Most investigators agree that health-care processes have a relatively modest role in explaining health disparities—perhaps explaining only 10–20% of the variation in health outcomes among different groups.4 On the other hand, health disparities resulting from health-care disparities clearly are in the purview of the people working in the health-care system and are amenable to change. Health professionals have a particular obligation to eliminate disparities in access to and quality of care that contribute to health inequity for vulnerable populations.

BEHAVIORAL MODEL APPLIED TO HEALTH-CARE DISPARITIES

Why is a patient like Mr. Dixon less likely than a patient like Mr. Mason to receive high-quality care? One of the most frequently used models for conceptualizing access to care is the behavioral model developed to explain differences in care received by different people or groups of people.5 The behavioral model proposes analyzing the care people receive by looking at three fundamental categories of factors: need, predisposing characteristics, and enabling resources. Gelberg and colleagues have revised the model based on their work with homeless populations, proposing a behavioral model for vulnerable populations that includes both traditional categories and vulnerable domains (Table 2-1).6

| Need | |

|---|---|

Traditional Domains Perceived health • General population health conditions Evaluated health • General population health conditions | Vulnerable Domains Perceived health • Vulnerable population health conditions Evaluated health • Vulnerable population health conditions |

| Predisposing Characteristics | |

Traditional Domains Demographics • Age • Gender • Marital status • Veteran status Health beliefs • Values concerning health and illness • Attitudes toward health services • Knowledge about disease Social structure • Ethnicity • Education • Employment • Social networks • Occupation • Family size • Religion | Vulnerable Domains Social structure • Country of birth • Acculturation/Immigration/Literacy • Sexual orientation • Childhood characteristics • Residential history/Homelessness • Living conditions • Mobility • Length of time in the community • Criminal behavior/Prison history • Victimization • Mental illness • Psychological resources • Substance abuse |

| Enabling Resources | |

Traditional Domains Personal/Family resources • Regular source of care • Insurance • Income • Social support • Perceived barriers to care Community resources • Residence • Region • Health services resources | Vulnerable Domains Personal/Family Resources • Competing needs • Hunger • Public benefits • Self-help skills • Ability to negotiate system • Case manager/Conservator • Transportation • Telephone • Information sources Community resources • Crime rates • Social services resources |

It is axiomatic that people with a greater need for health care, all other things being equal, make greater use of health-care services. For example, a patient with diabetes has a greater than average need for health care. How much need depends on the severity of the diabetes, and whether there are complications or other chronic conditions. Having diabetes per se does not necessarily constitute a disparities-related vulnerability (although it is certainly a risk factor for adverse health outcomes such as heart disease and kidney failure). On the other hand, some clinical conditions may in and of themselves confer a social vulnerability. Prime examples are the socially stigmatizing conditions of learning disabilities, mental illness, and substance use, where the conditions themselves can alter the presentation of illness and where health professionals’ perceptions can contribute to inadequate care.

In the preceding case, might there have been some difference between Mr. Dixon’s clinical presentation that made it appear that Mr. Dixon had less clinical need for urgent coronary stenting?

Predisposing characteristics refer to health beliefs and culture, care-seeking behaviors, trust in health care and other social institutions, and related characteristics that may influence whether, when, and from whom an individual decides to obtain health care when needed. Health education may assist individuals to make well-informed decisions about using health-care services.

Patients from vulnerable groups such as ethnic minorities may understandably be less trusting of the health-care system because of personal or collective experiences of social injustice in that setting. One glaring example of this is the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.7 Between 1932 and 1972, the US Public Health Service conducted an unethical study at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in which African-American patients with syphilis were left untreated in order to observe the “natural” progression of syphilis—despite the discovery in the 1940s of penicillin as a highly effective treatment for this infection. African Americans cite the Tuskegee experiment as one reason for concern that medical research may exploit rather than aid them.8 Personal experience of racism contributes even more significantly to mistrust of medical care.9

The human resources deployed in the health-care system also may contribute to vulnerable patients’ mistrust of the health-care system and predisposition against using health-care services. Physicians tend to come from backgrounds that are more privileged and, by virtue of their occupation and income, have a socioeconomic status that on average is higher than that of the population of patients they serve. In the United Kingdom, nearly 60% of medical students come from families in the top 20% of income distribution.10 This can contribute to a sense of social distance between physicians and patients. In addition, the ethnic and cultural backgrounds of many health professionals are different from the characteristics of patients who seek their services. African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans are underrepresented within the health professional workforce. These three minority groups comprised 26.6% of the US population 16 years and older during 2008–2010, but contributed only 11.3% of the physicians, 17.2% of physician assistants, 15.1% of the registered nurses, 9.0% of the dentists, and 9.8% of pharmacists in the United States.11 African-American patients cared for by African-American physicians report that their physicians include them more in medical decision making and that they are more satisfied with their care than those who are cared for by non–African-American physicians.12 Similarly, Spanish-speaking patients are more satisfied with the care they receive from Spanish-speaking physicians.13 In the United Kingdom, South Asian patients report higher enablement after consultations with physicians with whom they share a language.14

Is it possible that both Mr. Mason and Mr. Dixon were offered urgent cardiac catheterization by their physicians, but Mr. Dixon might have declined to have the procedure performed because of less trust in his physicians and nurses?

Enabling resources are factors that promote access to effective health care. These resources may be at the community or personal level. Community-level enabling resources are the assets of the local health-care system and other social services. The presence of a community clinic that provides financial assistance for low-income patients or has interpreters on site are enabling resources that contribute to improving access to care, particularly in low-income and minority communities where private physicians are less likely to practice.15 The access to care barriers associated with the scarcity of physicians in certain communities can be compounded by the lack of another community “enabler,” reliable transportation.

Among the most obvious and fundamental resources that make care easier for a person to access are financial resources: health insurance and the financial means to pay for those health-care costs not covered by insurance. Lack of health insurance is the single greatest impediment to access to care in the United States and results in unnecessary morbidity for affected individuals and inefficient use of health-care resources.16 Numerous studies have demonstrated that the uninsured are less likely than those with health insurance to have a regular source of health care, have fewer physician visits, are less likely to receive appropriate preventive services, and are more likely to delay receiving needed medical care. The uninsured are 30% to 50% more likely than privately insured persons to have some deterioration in their health resulting from a chronic condition such as diabetes or asthma that ultimately necessitates a hospitalization that could have been prevented with timely ambulatory care.17

Other research has demonstrated that the uninsured present for care with more advanced stages of cancer, including breast, colorectal, prostate, and skin cancers. Delay in diagnosis is one of the reasons that the uninsured have shorter life expectancies than insured persons. The Institute of Medicine estimates that the age-specific mortality rate is 25% higher in the uninsured than in the privately insured population.18

Not surprisingly, socioeconomic class is a strong predictor of health insurance status. Although 80% of the uninsured live in families with a working adult, the majority of uninsured persons have family incomes falling at the lower end of the income scale. Without financial assistance, these individuals have a limited ability to purchase health insurance coverage and few personal financial resources to allow them to overcome barriers to care associated with the lack of health insurance.

Until the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 and its implementation in 2014, many low-income individuals were eligible only for public coverage on an emergency basis through Medicaid when they became so ill that they required hospitalization. Patients with a chronic disease who only have episodic health insurance coverage for hospitalizations are less likely than those with continuous coverage to receive appropriate treatment in the ambulatory setting that could prevent the pain and suffering associated with complications of their illness.19 The impact of this is apparent in cross-national comparisons with countries that have universal health insurance coverage. For example, the United States has greater disparities in hypertension control across socioeconomic groups than the United Kingdom where health insurance coverage is universal.20

Individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely than whites to be uninsured, a situation that contributes to racial and ethnic disparities in health care. In 2012, prior to the full implementation of the ACA in the United States, 29% of Latinos, 19% of African Americans, 15% of Asians, and 11% of non-Latino whites were uninsured.21 Variations in average income between racial and ethnic groups explain much, but not all, of the differences in rates of health insurance by race and ethnicity.

Might it have been the case that Mr. Dixon was uninsured, and that is why his physicians did not provide the same resource-intensive care received by Mr. Mason?

HEALTH-CARE DISPARITIES: THE EVIDENCE

As discussed in Chapter 1, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status are powerful predictors of a person’s health status. These same factors are also strongly associated with access to health care and quality of care. There is ample evidence indicating that the differences in care received by Mr. Mason, a high-income white man, and Mr. Dixon, a working-class African-American man, are indicative of pervasive differences in processes of care in the United States based on race/ethnicity and class. Reported disparities in care related to income are worse in the United States than in countries that provide universal health insurance coverage.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree