Health Outcomes in Epilepsy: The Influence of Psychiatric Comorbidity and Other Factors

Zarya A. Rubin

Frank Gilliam

Psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression, are known to negatively affect health outcomes and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in a variety of neurological and non-neurological conditions (1,2,3,4,5,6). Depression is extremely common among patients with concomitant medical illness, and ranks second only to hypertension as the most common chronic condition in medical outpatients (7). Despite this high prevalence and enormous impact on health and quality of life (QOL), depression is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated (6).

By looking at results from the general medical and neurological literature on the contribution of depression to health outcomes, we can situate epilepsy, a chronic medical and neurological condition with extremely high rates of depression, in the larger picture.

Depression and Health Outcomes in Medical Illness

The last decade has seen an emerging interest in the relationship between depression and overall HRQOL in the setting of medical illness.

Hays et al. evaluated 1,790 patients with depression and various chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease for functional status and overall well-being (3). After 2 years of follow-up, the depressed patients were found to have deficits in multiple functional domains and well-being, which equaled or exceeded those of the medical patients (3).

In a multicenter study by Wells et al. 11,242 patients with either depression, chronic illness, or no illness were compared and described in terms of functional status and overall well-being (4). Depressed patients fared far worse than patients suffering from eight major chronic medical conditions, and these effects were additive for patients with medical illness and comorbid depression (4).

A recent study in the American Heart Journal showed that depression was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and hospitalization in patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction (8). Additional studies have shown that depression not only affects morbidity and mortality among survivors of cardiac

events but also predicts diminished QOL, accounting for 49% of the variance in QOL scores after myocardial infarction (9,10).

events but also predicts diminished QOL, accounting for 49% of the variance in QOL scores after myocardial infarction (9,10).

In a smaller study conducted by Drent et al. in patients with sarcoidosis, the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) was used to assess the QOL (11); depressive symptoms were characterized by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Multivariate regression analysis showed that 86% of the variance on QOL scores could be explained by depressive symptoms (11).

Akashiba et al. evaluated the QOL of depressed patients with sleep apnea, compared with those with sleep apnea alone, using the SF-36 (Medical Outcomes Short Study Form) and Zung self-rated depression scale (SDS). Six of eight domains on the SF-36 were significantly lower in the patients with depression (12).

Depression and Health Outcomes in Neurological Illness

Depression and its impact on QOL measures have been studied in various neurological conditions, including migraine, multiple sclerosis, stroke, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

In a meta-analysis of factors influencing QOL after a stroke, the variables that were negatively associated with stroke survivors’ QOL included psychological impairment, severity of impairment, severity of aphasia, inappropriate reactions to illness and pessimism, and inability to return to work. Twenty-two percent of the variance in QOL scores was explained by depression, functional ability, and socialization (13).

In a nationwide study of patients with migraine in France, migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) score, SF-12 QOL scores, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) were determined in more than 10,000 subjects (migraine patients, 1,957; controls, 8,287) (14). It was found that 50.6% of migraine subjects were depressed or anxious, and the perceived treatment efficacy, treatment satisfaction, and overall QOL were lower in the group with these comorbid psychiatric illnesses (14).

In a small study of depression and QOL among patients with ALS, 43% of subjects were found to be depressed, and lower scores on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale corresponded to lower scores on the psychological well-being domains of the McGill QOL scale. Interestingly, disease severity did not correlate with QOL (15).

Janssens et al. examined the relationship between comorbid anxiety and depression and their influence on disability status and QOL in patients with MS. Disability was measured using Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores; anxiety and depression were assessed using the HADS, and the SF-36 was used to characterize overall QOL. Although the EDSS directly influenced SF-36 scores, when adjusted for depression and anxiety, disability no longer contributed to the scores on the mental health and general health scales (16).

The Concept of Health- Related Quality of Life in Epilepsy

Epilepsy affects more than two million people in the United States, with total annual estimated health care costs of US$12.5 billion (17,18). It is a complex disorder that may impact every aspect of a patient’s life, from physical and cognitive effects to social and vocational challenges, to personality and mood changes, and therefore is an ideal condition in which to study the impact of HRQOL measures.

Measures of success in treating medical illness have traditionally been thought of in terms of freedom from disease or other intermediate quantifiable endpoints such as reduction in systolic blood pressure, serum glucose, or seizures (19). However, in the last decade, the emergence of QOL as a valid and significant indicator of health in patients with epilepsy is beginning to change that perception.

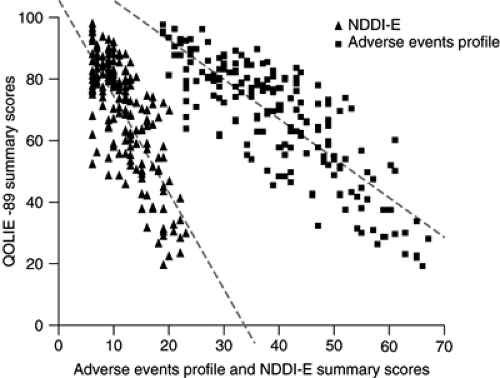

The first use of QOL in relation to health care was in 1948 with the development of the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale. The 100-point scale defined a patient’s ability to perform various activities of daily living, (where 100 is capable of performing all normal activities, and 0 is dead) (20,21). In 1995, Devinsky et al. developed the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-89), an 89-item disease-specific inventory to help characterize the impact of epilepsy on patients’ global functioning (22). Since then, a QOLIE-10 (23), has been developed in addition to other more specific inventories relating to aspects that contribute to overall QOL in patients with epilepsy, such as medication side-effects (adverse events profile [AEP]) (24) and the Neurologic Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) (25), a newly developed tool to differentiate depression in epilepsy from antiepileptic drug (AED) and cognitive effects (Fig. 29.1).

Recently, Gilliam et al. systematically assessed the specific concerns of patients with recurrent seizures in a study of 81 consecutive patients with epilepsy (26). The most frequently cited concern was driving, at nearly 70%, whereas other significant factors listed by more than one third of patients included independence, work and education, social embarrassment, medication dependence, mood/stress, and safety.

It appears that the complete picture of the experience of epilepsy is more complex and detailed than previously thought, reaching beyond the seizures themselves and extending into multiple aspects of patients’ overall health. Although patient-oriented outcome measures are not intended to replace traditional indicators of health status in epilepsy, such as seizure frequency or severity, they may offer additional information that allows us to expand our knowledge of the experience of epilepsy and treat our patients better.

This review will examine the contribution of mood status, medication effects, seizure frequency, and outcomes of epilepsy surgery to overall HRQOL in patients with epilepsy.

Depression and Health- Related Quality of Life

Epilepsy has extremely high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, with depression being the single most common illness, with a prevalence of up to 55% among patients with refractory epilepsy (27,28,29,30). Recent studies have consistently shown a negative correlation between mood status and overall QOL in patients with epilepsy, and depression alone often accounts for most of the variance in QOL scores (31,32,33).

In 1996, Perrine et al. examined the relationship between neuropsychological functioning, mood, and QOL in patients with epilepsy at 25 centers across the United States. Results demonstrated that mood had the highest correlation and explained the greatest amount of variance (46.7%) in validated QOL measures (QOLIE-89) (33).

Lehrner et al. studied patients with refractory epilepsy and measured degrees of depression and overall HRQOL using instruments validated for native German speakers (34). Forty-five percent of patients were found to have depression, and on multiple regression analysis depression scores proved to be the major predictor on all six HRQOL scales. This was a linear correlation, with more severe depression scores predicting a lower QOL. Seizure frequency was not found to predict either depressive mood or HRQOL score (34).

Cramer et al. studied the influence of comorbid depression on HRQOL for patients with epilepsy using a postal survey and the QOLIE-89 and CES-D scale (35). Other variables such as seizure frequency, medications, degree of disability, and economic factors were also incorporated into the analysis. Patients were categorized into one of three groups: no depression, moderate depression, or major depression, depending on CES-D scores. All QOLIE-89 subscales and total scores were determined by degree of depression but were not significantly influenced by seizure type. Total scores decreased by 17 to 23 points between major and moderate depression, by 8 to 13 points between moderate and no depression, and by 30 to 32 points between major and no depression (35) (Fig. 29.2, Table tab29.1).

In a recent study, Loring et al. examined the relative contribution of epilepsy-specific concerns, cognitive variables, and other clinical factors to overall HRQOL in patients undergoing evaluation for epilepsy surgery (31). Patients were evaluated with the QOLIE-89, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2 (MMPI-2), BDI, Epilepsy Foundation of America (EFA) Concerns Index, and various measures of general intelligence and cognitive function. Regression analysis revealed that the two most important factors associated with overall score on the QOLIE-89 were depressive symptomatology (accounting for 57% of the variance) and seizure worry (accounting for 42% of the variance) (31) (Figs. 29.3 and 29.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree