CHAPTER 13 Health promotion

Introduction

Health promotion consists of a set of activities and programs that aim to facilitate wellness, prevent illness and foster recovery for individuals, communities and wider society. It is a relatively new endeavour in the health field and ‘continues to develop, drawing on the knowledge and methods of diverse disciplines and being informed by new evidence about health needs and their underlying determinants’ (Smith et al 2006 p 340). This chapter will examine the development of the health promotion movement from its emergence in the 1970s as a specific intervention to change individual health behaviours through to its evolution to the social determinants approach of the 21st century.

What is health promotion?

Health promotion consists of a range of strategies and activities that are designed to facilitate health and wellbeing and to prevent illness. Definitions of health promotion range from those that focus more on the individual and their personal responsibility for their health outcomes (O’Donnell 2008) to definitions that take account of the wider social, political and economic forces which influence the health of individuals, communities and wider society (World Health Organization 1998). The editor of the American Journal of Health Promotion, for example, defines health promotion as:

Whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health promotion more broadly as:

Protective and risk factors

Rickwood (2006), in distinguishing protective and risk factors for the development of and recovery from mental illness, states that protective factors for mental illness reduce the likelihood that a disorder will develop by reducing the exposure to risk, and by reducing the effect of risk factors for individuals exposed to risk. Protective factors also foster resilience in the face of adversity and moderate against the effects of stress; whereas, risk factors increase the likelihood that a disorder will develop, exacerbate the burden of an existing disorder and can indicate a person’s vulnerability. Both protective and risk factors include genetic, biological, behavioural, socio-cultural and demographic conditions and characteristics (Rickwood 2006) with some factors being internal to the person while others are external. Internal factors include genetics, disposition and intelligence while external drivers comprise the social determinants of health related to social, economic, political and environmental factors including the availability of opportunities in life and access to health services (CDH&A 2000a).

Protective factors assist the individual to maintain emotional and social wellbeing and to cope with life experiences including adversity. They can provide a buffer against stress as well as be a set of resources to draw upon to deal with stress (CDH&A 2000a p 53). Factors that have been identified as protective against mental illness in children, for example, include ‘family harmony; positive school environment; school achievement; a sense of self-worth; self-efficacy; coping skills; social skills; having a personal confidante; belonging to a positive peer group; and leading an active lifestyle’ (CDH&A 2000b p 118).

Risk factors increase vulnerability to mental illness and mitigate against recovery from mental illness. Risk factors for mental illness in children have been identified as: ‘family discord and violence; low family income; parental unemployment; parental substance misuse and mental health problems; coercive parenting style; poor monitoring and supervision at home and school; inconsistent behaviour management; poor peer relations and school alienation’ (CDH&A 2000b p 118).

History of health promotion

Health promotion commenced in the 1970s following the identification of lifestyle as being a major contributor to health and illness (Baum 2008) and the development of psychological models for understanding and changing health behaviours. The health belief model (see Ch 7) was especially influential in early health promotion campaigns and was viewed as the way forward in changing unhealthy lifestyle practices, particularly in relation to diet, physical activity, tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. Health promotion initiatives, at this time, mainly consisted of health education and counselling regarding lifestyle, illness prevention initiatives like mass vaccination and screening initiatives, and lifestyle education programs such as stress management.

Psychology and health promotion

Contributions to the field of health promotion by the discipline of psychology have been significant since the 1970s when psychological theories like the health belief model, transtheoretical model and health action process approach were first used in health education and counselling to bring about targeted individual behaviour and lifestyle changes. In later years, with the rise in the prevalence and burden of chronic illnesses in Western countries, the focus of health promotion efforts shifted from reducing mortality to reducing morbidity or the burden of disease (Taylor 2009). Additionally, psychological research that had initially focused on identifying risk factors shifted to understanding and facilitating ‘protective’ factors for health like resilience (Garmezy 1991).

In contemporary health promotion, psychological theory contributes to an interdisciplinary approach across the range of activities at all levels of intervention from that of the individual to that of wider population. Motivational interviewing, for example, is a psychologically based counselling intervention aimed at changing unhealthy behaviours. It utilises a client-centred, semi-directed approach and focuses on reasons for and against the change to motivate the person to change to a healthier lifestyle. In larger scale health promotion interventions behavioural and cognitive principles that are derived from psychological theory are incorporated in mass media health education campaigns, particularly those targeting lifestyle.

Primary health care movement and health promotion

During the 1980s it became apparent that health education and counselling approaches, on their own, were insufficient to bring about the required changes in many instances because people’s behaviour is also shaped by the social, political and economic environments in which they live (Raphael et al 2003). It was at this time that WHO (1986) released its seminal document – the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, which subsequently became the cornerstone of the health promotion movement (see Ch 4). The charter shifted the emphasis of health promotion from the individual and called on governments and health services to address the wider social, political and economic drivers of health. As a consequence health promotion became located in, and was central to, the emerging primary health care movement.

The shift from an individual to a societal and population focus precipitated a change in perceptions of responsibility for health away from the individual to wider society and the environments in which people live. While both individual and population-focused approaches have a role to play in contemporary health promotion practice, a population approach that addresses the determinants of health offers greater opportunity to influence health outcomes for a greater number of people. Nevertheless, individual approaches do continue to play a role in assisting an individual to engage in healthy lifestyle practices and can facilitate the utilisation of strategies of the Ottawa Charter in health care practice, for example, the development of personal skills through health education and counselling. Despite originating in the 1980s the Ottawa Charter remains relevant in the 21st century as a framework for health promotion, as evidenced by its frequent citing in the literature and its widespread utilisation in healthcare practice and programs (McQueen 2008).

Levels of intervention

The upstream/midstream/downstream distinction is best illustrated by the allegory popularised by John McKinlay, a medical sociologist. McKinlay’s story tells of a physician who was standing by a swiftly flowing river when a drowning man floated past. The physician jumped in the water and rescued the man. However, no sooner had the physician rescued him when another drowning person came by. Repeatedly, the physician rescued and resuscitated drowning people as they floated past. In fact the physician was so busy rescuing the drowning people that he did not have time to go upstream to see who was pushing them in (McKinlay 1974). This frequently repeated scenario is now an enduring primary health care metaphor that illustrates that while downstream interventions are effective in responding to a health problem they do nothing to address the actual upstream cause of the problem.

The medical model operates primarily as a downstream approach in which individuals with health problems seek assistance from their general practitioner or the healthcare system. An exception is mass immunisation programs, which are a biomedical intervention with an illness prevention focus. Downstream approaches occur mainly at the individual level. Psychosocial models, including primary health care, operate at all three levels. Table 13.1 summarises potential upstream, midstream and downstream approaches to reducing the dietary intake of saturated fats as suggested by Lytle & Fulkerson (2002).

Table 13.1 Reducing dietary intake of saturated fats

| UPSTREAM | MIDSTREAM | DOWNSTREAM |

|---|---|---|

| Tax foods high in saturated fats | Increase availability and access to foods low in saturated fats | Dietary advice to assist individuals to reduce their intake of saturated fats |

| Create price incentives for buying low saturated fat foods | Adapt recipes to reduce saturated fat content and consumption |

Primary, secondary and tertiary interventions

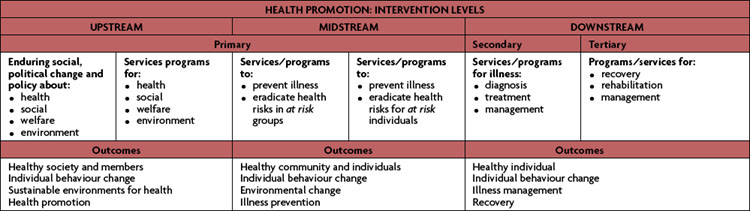

The terms primary, secondary and tertiary prevention are used to distinguish between levels of intervention that foster wellness, treat illness and restore function following illness (McMurray 2007). According to Kaplan (2000) primary prevention is distinct from healthcare service delivery which is the provision of treatment for health problems. At each level of intervention the goal of health promotion is to ensure that public policy is healthy, environments are supportive of health, community action is strengthened, personal skills are developed and that health services are re-oriented. In other words, that the strategies for health promotion as articulated in the Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) are implemented.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention refers to interventions that are, in the main, delivered downstream when symptoms, injury or illness are identified and treated as early as possible to restore health. It includes the range of health services that the general public will be most familiar with, for example, attending an accident and emergency department when injured or visiting a general practitioner when symptoms are present.

In addition to treating illness and health problems a further goal of secondary prevention is early intervention. Hence, some interventions will occur midstream, such as health screening like mammograms or hearing tests for infants. In this instance the purpose of early intervention is to identify and address health issues before they become a problem or to minimise the impact of an illness on the individual. An example of the effectiveness of early intervention was demonstrated by Hakama et al (2008) whose research found that the incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer was significantly reduced by population screening by undertaking cytological smears.

Tertiary prevention

Recovery, which is a goal of tertiary prevention, is a concept that evolved as part of the reform of mental health services that has occurred in Western countries over recent decades. A recovery approach has subsequently become an integral component of mental health clinical practice (Rickwood 2006). Recovery for the client refers to living well with a chronic illness or disability. It may include learning about the condition and what triggers episodes, and making lifestyle changes. For the health professional it means not only working with the client to manage the symptoms of the health problem, but also to work with the client to manage a life lived with disability. The approach acknowledges that lifestyle can positively or negatively influence the chronic illness. Hence, a recovery approach encompasses more than merely treating or managing the symptoms of the illness. It includes recognition of and attention to social economic and political aspects of people’s lives as well as their illness or disability. In a recovery-focused model the health professional and the client work together in partnership to maximise the quality of life for the person living with chronic illness or disability.

While, to date, the recovery model has mainly focused on minimising the disability from mental illness to enable people with mental illness to live well despite their condition, the approach does have wider applicability for people who live with other chronic illness and for those health professionals who work with people living with chronic illness or disability. An example of a recovery-focused tertiary intervention that has a broad application is the ‘Flinders model’ of chronic disease self-management developed by health professionals and researchers at Flinders University, Adelaide. The model is underpinned by cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles. It utilises a partnership approach in which the health professional and client collaborate on problem identification, goal setting and developing an individualised care plan. The model has proved to be effective in facilitating self-management by people with chronic health conditions and improves health-related behaviour and health outcomes (Harvey et al 2008).

In summary, health promotion can be implemented at primary, secondary or tertiary levels to target individual, community or population health needs. Secondary and tertiary approaches are effective in diagnosing, treating and managing illness. However, as McKinlay’s primary health care metaphor tells us, responding to health problems with a treatment response will deal with the symptoms but not necessarily the cause of the health problem. Therefore, in order to address the cause of a health problem, it is evident that primary intervention, alongside treatment and recovery models, is required. Table 13.2 summarises the health promotion levels of intervention.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree