(Modified from Wansink 2004)

Although the environmental factors outlined in Figure 6-1 will be discussed individually, it is important to realize that they operate simultaneously. Consider the end-of-the-year weight gain that many experience over the holidays (14, 15). For most, this weight gain is a result of both the eating environment and the food environment. The holiday eating environment directly encourages over-consumption because it involves parties (long eating durations), convenient leftovers (low eating effort), friends and relatives (eating with others), and a multitude of distractions. At the same time, the food environment—the salience, structure, size, shape, and stockpiles of food—simultaneously facilitates over-consumption.

Why Do Environmental Cues Make Us Overeat?

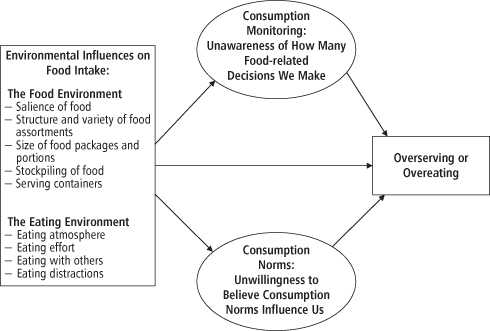

It has often been suggested that we overeat from larger portions because we have a tendency to “clean our plate” (6). While this may describe why many people eat what they are served, it does not explain why they do so or why they may over-serve themselves to begin with. Figure 6-1 suggests two reasons why portion size may have a ubiquitous, almost automatic influence on how much we eat: first, portion sizes create our consumption norms; second, we underestimate the calories in large portions.

Environmental Cues Bias Consumption Norms

People can be very impressionable when it comes to how much they eat. There is a flexible range as to how much food an individual can eat (16) and one can often “make room for more” (17). For this reason, a person may be quite content eating from 170 g to 285 g of pasta for dinner without feeling overly hungry or over-full.

A key part of Figure 6-1 is the role of consumption norms (18). For many individuals, determining how many grams of pasta to serve themselves for dinner is a relatively low-involvement behavior and is a difficult nuisance to continually and accurately monitor. Sometimes, people rely on consumption norms to help them determine how much they should consume. Food-related estimation and consumption behavior can be based on how much one normally buys or normally consumes. Yet consumption can also be unknowingly influenced by other norms or cues that are present in the environment. An important theme of this commentary is that larger packages in grocery stores, larger portions in restaurants, and larger kitchenware in homes all suggest a consumption norm that very subtly influences how much people believe is appropriate to eat.

In one series of studies we are currently conducting, we ask people to serve the amount of four different foods (ice cream, popcorn, soup, and M&Ms) they thought would be typical, reasonable, and normal to consume. However, we vary the size of the bowls (medium vs. large) we give them. Regardless of the food and regardless of the person, the larger the bowl people are given, the larger the consumption norm they believe is normal.

Large-size packages, large-size restaurant portions, and large-size dinnerware all have one thing in common—they suggest that it is appropriate, typical, reasonable, and normal to serve larger servings. These all influence our personal consumption norm for that situation, implicitly or at least perceptually suggesting that it is more appropriate to eat more food than smaller plates or smaller packages would suggest. The use of consumption norms, as with normative benchmarks in other situations, may be relatively automatic and may often occur outside of conscious awareness (19). This is what makes these norms so powerful.

Even when made aware of it, most people are unwilling to acknowledge that they could be influenced by anything as seemingly innocuous as the size of a package or plate. Even when shown that larger packages and plates lead them to serve an average of 31% more food than matched control groups, 98% of the diners in these field studies resolutely maintained that they were not influenced the size of package or plate they were given (20).

We Underestimate the Calories in Large Portions

The second key part of Figure 6-1 is the role of consumption monitoring. Not surprisingly, a major determinant of how much people eat is often whether they deliberately monitor or even pay attention to how much they eat (21, 22). When people pay close attention to what they eat, they tend to eat less. Our ability to monitor our consumption can help reduce discrepancies between how much we eat and how much we believe we eat. Our environment can have an exaggerated influence on consumption because it can bias or confound estimates of how much one has eaten or how often one has been actively making decisions about starting or stopping an eating episode.

In lieu of monitoring how much they are eating, people can use cues or rules of thumb (such as eating until a bowl is empty) to gauge the amount of food consumed. Unfortunately, using such cues and rules of thumb can yield inaccurate estimates. In one study, unknowing diners were served tomato soup in bowls that were refilled through concealed tubing that ran through the table and into the bottom of the bowls. People eating from these “bottomless” bowls consumed 73% more soup than those eating from normal bowls, but estimated that they ate only 4.8 kcal more (23).

Our ability to monitor or estimate how many calories we eat becomes increasingly less accurate as portion size increases. It used to be believed that obese people had a greater tendency to underestimate the calories in their meals than people of normal weight (24). This was even believed to be a contributing cause of their obesity (25). Recent studies have shown that this apparent effect is due to the size of the meals (the calorie content), not the size of people (26). People of all sizes—even registered nurses and dieticians—are equally inaccurate in their estimations of calories from large portions (27). While it initially appears that heavier people are worse estimators of what they eat, a person of normal weight is just as inaccurate at estimating a 2,000 kcal lunch as a heavy-set person. It is just that obese people eat a lot more 2,000 kcal lunches. With any large-sized portion of food, a lot of calories can be eaten before there is any noticeable sign that the supply has decreased. It does not matter how accurate or how diligent a person is at estimating calories; larger portions obscure any such changes until it is almost too late.

Are We Aware of the Consumption Norms that Have Led Us to Overeat?

People can often “make room for more” (28) and be influenced by consumption norms around them (see Figure 6-1), possibly because determining how much to eat or drink is a mundane and relatively low-involvement behavior that is a nuisance to monitor (29). Many seemingly isolated influences on consumption, such as package size, variety, plate size, or the presence of other, may suggest how much is typical, appropriate, or reasonable to eat or drink.

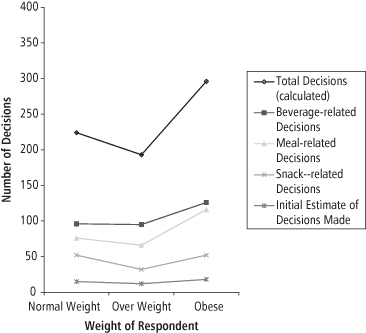

As with normative benchmarks in other situations, benchmarks when eating may often be relatively automatic and occur outside of conscious awareness. Indeed, when asked how many food-related decisions they make in a particular day, the average person estimates between 15 and 30. In reality, a number of different studies have shown that the typical person makes between 200 and 300 food-related decisions a day (20). Moreover, this appears to vary by BMI. Those who are obese (BMI >30) make the most decisions, but estimate themselves as making the fewest (see Figure 6-2).

Even when consumption norms do influence us, some evidence suggests that people are generally either unware of their influence or that they are unwilling to acknowledge it (30). Past evidence of the presence or absence of this awareness has sometimes been suggested in the context of laboratory experiments (31). The problem with trying to generalize from such artificial contexts is that people are generally aware that some manipulation has occurred and they may be reluctant to acknowledge any influence, primarily because they react against it. This phenomenon can best be observed in the context of controlled field studies conducted in natural environments (2).

The basic organizing framework for such studies is that both the food environment and the eating environment directly contribute to consumption volume. Importantly, however, they also contribute to consumption volume indirectly through the mediated impact they have on consumption norms and on perceived consumption volume. For instance, while having dinner with a friend can have a direct impact on consumption (because of the longer duration of the meal), it can also have an indirect influence. This can be due to people following the consumption norms set by their friend or because their enjoyment distracts them from monitoring how much they consume. Although these factors will be discussed individually, they often operate simultaneously. For instance, the usual holiday weight gain of 0.37 kg (15) is probably a combined result of consumption norms, food salience and availability, group sizes, and other factors.

How the Food Environment Encourages Mindless Eating

When a craving for one of our favorite foods sets in, we often find it difficult to resist that temptation. Food consumption can often be related to the perceived taste or cravings associated with foods (32, 33), and such cravings can differ among sex and age groups (33).

Despite this link between palatability and consumption, people don’t gorge exclusively on the tastiest, most appealing foods (34). Indeed, people can unknowingly over-eat unfavored foods as much as they do their favorites. This section examines the food-related environmental factors that influence consumption volume but which are unrelated to palatability. They can be characterized as the “Five S’s” of the food environment because they refer to a food’s 1) salience, 2) structure, and 3) size, and also 4) whether it is stockpiled, and 5) how it is served.

Salient Food Promotes Salient Hunger

Food has a powerful effect on our visual and olfactory senses, and the mere presence of food can prompt unplanned consumption even when we are not hungry (35–36). For instance, when 30 Chocolate Kisses were placed on the desks of secretaries, 46% more were consumed from the clear candy dishes than the opaque ones (37). Similarly, people given sandwich quarters wrapped in transparent wrap were found to eat more than those who were given sandwiches in nontransparent wrap (38).

It had been believed that such increased intake of visible foods occurred because their salience served as a constant consumption reminder. While part of this may be cognitively based, part of it is psychologically based. Simply seeing or smelling a favorable food can increase reported hunger (39–42) and can stimulate salivation (43, 44), which is correlated with greater consumption (45). Recent physiological evidence suggests that the visibility of a tempting food can enhance actual hunger by increasing the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward (46). The effect of these cues can be particularly strong with unrestrained eaters (47).

Although the sight and smell of a food may be the most prominent reminders of its presence, salience can also be prompted by internal stimuli, like memories or other psychological connections (48). One food-recall study even suggested that eating episodes associated with internally generated salience may ultimately lead to greater consumption than those associated with externally generated salience (49). Another study manipulated the salience of canned soup by asking people to write a detailed description of the last time they ate soup, the idea being that those who hadn’t eaten soup in a long time would be internally prompted to consume more. Those who increased the salience of soup in this way tended to consume 2.4 times as much canned soup over the next two weeks as did their counterparts in the control condition (50).

Structure and Perceived Variety Can Drive Consumption

Rolls and her colleagues have shown that if consumers are offered a plate with three different flavors of yoghurt, they are likely to consume an average of 23% more yoghurt than if offered only one flavor (51). The trend of greater consumption as prompted by a greater variety of a food (52, 53) has been found across a wide range of ages (54) and in both sexes (55, 56).

Recently, however, Kahn and Wansink have shown that simply increasing the perceived variety of an assortment also can increase consumption (11). In one study they gave people an assortment of 300 chocolate-covered M&M candies which were presented in either seven or 10 different colors. Although the candies were identical in taste, people who had each been given a bowl with 10 different colors ate 43% more (91 vs. 64 candies) over the course of an hour than those who were given bowls with seven different colors. Interestingly, 10 colors is 43% more colors than seven. In another study, participants were offered two different assortments of six flavors of jelly beans, one arranged by color and the other mixed together. Those offered the disorganized assortment rated the assortment as having more variety, and they ate 69% more (22 vs. 13) than those offered the organized assortment (11).

Thus, simply changing the arrangement of a food (such as the organization, duplication, and symmetry) without an actual increase in variety can increase consumption. One reason this occurs is because increases in perceived variety make a person believe he or she will enjoy the assortment more. A second reason this occurs is because increasing the perceived variety can concurrently suggest an appropriate amount to consume (the consumption norm) in a particular situation (11).

For researchers, it is important to know that perceptions of variety (45–47) —and not just actual variety—can influence consumption. For consumers, it is more important to keep in mind that our immediate food environments are malleable and can be adjusted and designed to better control intake (see Table 6-1).

Table 6-1 Changing Our Environment Changes Our Consumption

Adapted from ref. (18).

| How Environmental Factors Influence Consumption | How Environmental Changes Can Help Reduce Consumption |

| The Eating Environment | |

| Eating Atmospherics: Atmospherics Influence Eating Duration |

|

| Eating Effort: Increased Effort Decreases Consumption |

|

| Eating with Others: Socializing Influences Meal Duration and Consumption Norms |

|

| Eating Distractions: Distractions Initiate, Obscure, and Extend Consumption |

|

| The Food Environment | |

| Salience of Food: Salient Food Promotes Salient Hunger |

|

| Structure and Variety of Food Assortments: perceived variety drives consumption |

|

| Size of Food Packages and Portions: packages and portion size suggest consumption norms |

|

| Stockpiling of Food: stockpiled food is quickly consumed |

|

| Serving Containers: serving containers that are wide or large create consumption illusions |

|

The Size of Packages and Portions Suggest Consumption Norms

There is overwhelming evidence that the size of food packaging and portions has steadily increased over the past 30 years (57, 58). While this is a trend in much of the developed world, it is particularly true in the US and may help explain the greater obesity rate in that country (4, 59, 60). Rozin and his colleagues have shown that the size of packages and portions in restaurants, supermarkets, and even in recipes is much larger in the US than in France, which is often considered to be a more food-centric country (61).

The implications that this trend has for consumption are myriad, as it is well known that the size of a package can increase consumption (62), as can the size of portion servings in kitchens (63, 64) and restaurants (65). Interestingly, package and portion size have also been shown to increase consumption of unfavorable foods. For instance, when movie-goers in a Philadelphia suburb were given either medium- or large-sized containers of 14-day-old popcorn, individuals provided large-sized containers ate 38% more despite its quality (11). An important program of child development research by Birch and Fisher has shown that portion size first begins to influence children between 3 and 5 years of age (6, 66). Because of its developmental indications, the tendency for children to let portion size influence their consumption volume has been referred to as the “clean-your-plate” phenomenon or the completion principle (67). However, neither of these psychological driver theories explains why large packages also increase the pouring of less-edible products such as shampoo, cooking oil, detergent, dog food, and plant food. Nor do they explain why large packages of M&Ms, chips, and spaghetti increase consumption in studies where even the smaller portions were too large to eat in one sitting (62, 68). In both situations, people poured or consumed more even though there was no possibility of “cleaning one’s plate.”

A more likely explanation of why large packages and portions increase consumption may be because they suggest larger consumption norms (recall Figure 6-1). These norms implicitly suggest what might be construed as a “normal” or “appropriate” amount to consume. Even if one does not clear the plate or finish the contents of a package, the amount of the food presented gives one liberty to consume past the point where he might have stopped with a smaller, but still unconstrained, supply.

Stockpiled Food Is Quickly Consumed

The presence of large stockpiles of food products at home (such as multi-unit packages purchased at wholesale club stores) can make those products more visible and salient than those contained in one-unit or smaller packages. Not only are stockpiled products by their very nature visually conspicuous, they are often stored in salient locations until they are depleted to more manageable levels (69). Because visibility and salience can stimulate consumption frequency, it is often alleged that bulk-buying or stockpiling causes over-consumption and may promote obesity.

To investigate this, Chandon and Wansink directly stockpiled people’s homes with either large or moderate quantities of eight different foods. They then monitored each family’s consumption of these foods for two weeks. It was found that when convenient, ready-to-eat foods were initially stockpiled, they were eaten at nearly twice the rate as non-stockpiled foods (an average of 112% faster) (69). After the eighth day, however, the consumption of these stockpiled foods was similar to that of the less stockpiled foods, even though plenty of both remained in stock. Part of this eventual decrease was due to “burn-out” or taste satiation (70), but another factor was that the inventory level of these foods dropped to the point where they became much less visually salient (50).

To investigate the link between the visibility of stockpiled food and obesity, Terry and Beck (71) compared food storage habits in homes of obese and non-obese families. Curiously, while their first study showed that stockpiled food tended to be visible in the homes of obese families, their second study showed the opposite. In general, however, more studies have demonstrated that stockpiled products tend to be visually salient, and this is one important reason why they are frequently consumed.

Serving Containers that Are Wide or Large Create Consumption Illusions

Nearly 72% of a person’s calorie intake is comprised of foods dished out from serving aids such as bowls, plates, glasses, or spoons (72). Consider drinking glasses and the vertical–horizontal illusion. Piaget and others have shown that when people observe a cylindrical object (e.g., a drinking glass), they tend to focus on its vertical dimension at the expense of its horizontal dimension (73–75). Even if the vertical dimension is identical to that of the horizontal dimension, people still tend to overestimate the height by 18–21%. This general principle explains why many people marvel at the height of the St Louis Arch, but not at its identical width.

In the context of drinking glasses, when people examine how much soda they have poured, there is a fundamental tendency to focus on the height of the liquid that has been poured and to downplay its width. To prove this, Wansink and van Ittersum conducted a study with teenagers at weight-loss camps (as well as a subsequent study with non-dieting adults) and showed that this basic visual bias caused teenagers to pour 88% more juice or soda (and subsequently consume more) into short, wide glasses than into tall, narrow glasses that held the same volume (76). These teenagers believed, however, that they poured half as much as much as they actually did.

This tendency held true in a study conducted with veteran Philadelphia bartenders. When asked to pour 1.5 oz of gin, whisky, rum, and vodka into short, wide (tumbler) glasses, these bartenders poured 26% more than when pouring into tall, narrow (highball) glasses (76). Experience or confidence in one’s estimations (the bartenders had both) cannot supersede the fundamental susceptibility to the vertical/horizontal illusion.

What about the size of plates and bowls? The size-contrast illusion suggests that if we spoon 100 g of mashed potatoes onto a 12-inch plate and 100 g onto an 8-inch plate, we will underestimate the total amount spooned onto the larger plate because of its greater negative space, even though they contain exactly the same amount (76). That is, the size-contrast between the potatoes and the plate is greater when the plate is 30 cm in diameter than when it is 20 cm.

A study at an ice cream social showed similar results. People who were randomly given 680 g bowls dished out and consumed 15–38% more ice cream than those who were given 450 g bowls (77). If a person intending to cut back on consumption decides to eat half a bowl of cereal, he had better pay attention to the size of the bowl. “Half a bowl” only gains meaning when it is put into the context of the serving bowl being used, the size of which acts as a perceptual cue influencing how much is served and consumed. Even if these perceptual cues are inaccurate, they offer cognitive shortcuts that can allow better serving behaviors with minimal cognitive effort.

The effect of spoon size on the amount taken appears to be similar. When cough medicine was given to health center patients, the size of the spoon they were given increased the dosage they poured by 41% over the recommended dosage level (78).

How the Eating Environment Stimulates Consumption

What causes us to begin eating and finally decide to stop? One study asked restrained dieters to maintain a consumption diary and to indicate what caused them to begin and stop eating (79). Aside from hunger, people claimed they started eating because of the salience of food (“I saw the food”), the social aspects of eating (“I wanted to be with other people”), or simply because eating provided them with something to do (“I wanted something to do while watching TV or reading”). When asked why they stopped eating, some of them pointed to environmental cues (such as the time or the completion of the meal by others), which served as external signals that the meal should be over (80). Others stopped eating when they ran out of food, and still others stopped because the television program they were watching ended or because they were at a stopping point in their reading.

These findings are consistent with other research (81) that suggests people may have continued to eat had they been given more food, more time to eat, or more television to watch. These responses relating to consumption start and stop times illustrate four important consumption drivers in the eating environment: 1) eating atmospherics; 2) eating effort; 3) eating with others; and 4) eating distractions. These will each be discussed in turn.

Atmospherics Influence Eating Duration

Atmospherics refer to ambient characteristic, such as temperature, lighting, odor, and noise, that characterize the immediate eating environment. Consider the direct physiological influence that temperature has on consumption. People tend to consume more during periods of prolonged cold temperatures than during periods of hot temperatures (82) because the brain sends signals to the body to eat or drink something in order to either raise body temperature or lower it. People eat more in prolonged cold temperatures precisely because the body needs more energy to warm itself and maintain its core temperature (83). In prolonged hot temperatures, the body needs more liquid to cool and maintain its core temperature (84), so the brain sends signals for the consumption of more liquids.

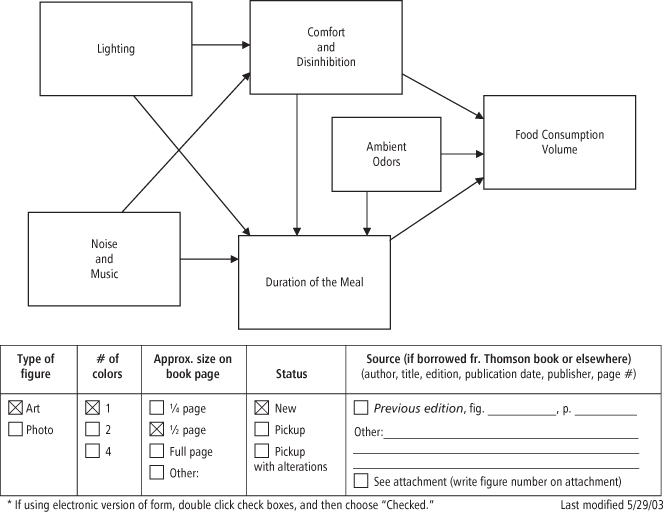

While temperature has direct physiological influences on consumption, other atmospherics, such as lighting, odor, and noise, have a more indirect or mediated effect on consumption. These atmospherics are thought to influence consumption volume partly because, when favorable, they provide a more comfortable environment for consumption, increasing the time dedicated to eating (see Figure 6-3).

Figure 6-3 How Atmospherics Influence Food Consumption Volume

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree