(1)

Hospital Authority, 5/F, Hospital Authority Building 147B Argyle Street, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China

6.1 Kyphosis in Ankylosing Spondylitis

Kyphosis may affect the cervical and thoracolumbar spine. This chapter only discusses kyphosis affecting the thoracic and lumbar spine. There are two subtypes (1) thoracic kyphosis with preservation of the physiological lumbar lordosis and (2) thoracic kyphosis with loss of the lumbar lordosis, forming a long C flexion deformity of the whole trunk.

6.2 Thoracic Kyphosis with Preservation of the Normal Lumbar Lordosis

Pulmonary function restriction occurs as part and parcel of the calcification or ossification process of the costovertebral joints. Thoracic kyphosis itself will not significantly affect pulmonary function. Therefore, the deformity is mainly a cosmetic issue and the amount of correction obtained is somewhat restricted, because of attachment to the stiff rib cage. The preferred method of correction is by a combined anteroposterior approach. Multiple anterior osteotomies should be performed at 6–8 levels, followed by multiple posterior osteotomies at comparable levels, with removal of small posterior wedges. Compression instrumentation of the posterior elements will result in opening of the anterior osteotomy sites, achieving a fair degree of correction.

6.3 Thoracic Kyphosis with Loss of the Normal Lumbar Lordosis

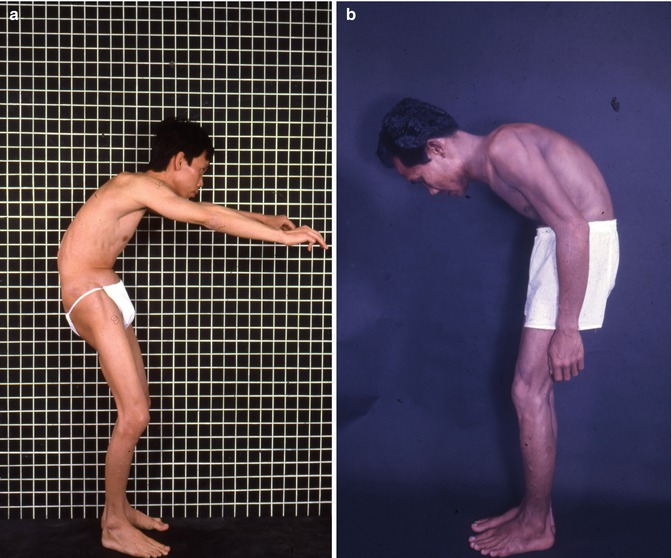

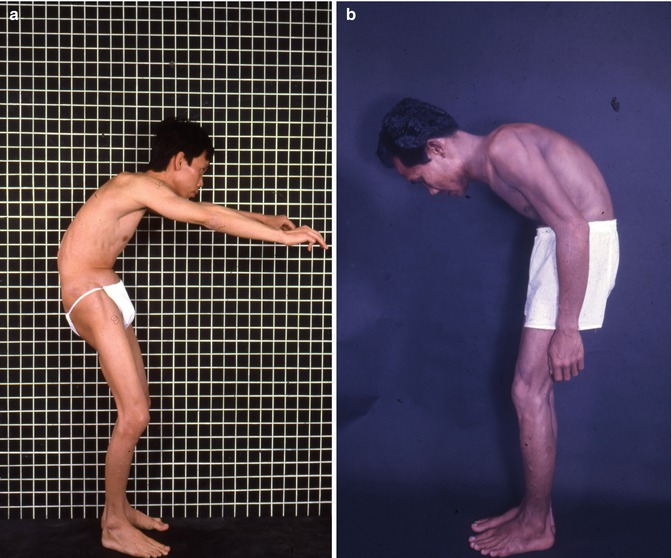

The whole trunk becomes a long C curve with the normal lumbar lordosis being converted into a kyphosis. There are two main problems in such patients. The first is the posture adopted by the patient, and the second is the forward visual arc. In order to stand reasonably upright and to maintain a good forward visual arc, the knees have to be flexed, thus resulting in a very tiring posture (Fig. 6.1a). When the patient stands with the knees extended, because of the truncal flexion deformity, and particularly when the neck is stiff as well, the forward visual arc will be limited to only a few feet in front (Fig. 6.1b). Such patients have great difficulty looking at near objects in front of them, or when observing oncoming traffic to safely cross the road.

Fig. 6.1

(a) Patient needs to flex knees to achieve forward vision. (b) With knees extended, posture very tiring, and cannot see forwards

Another factor that may cause a flexion deformity of the trunk is the presence of fixed flexion deformity of the hips. When the latter is significant, it should be corrected either by soft tissue releases or total joint replacement before considering an osteotomy of the lumbar spine.

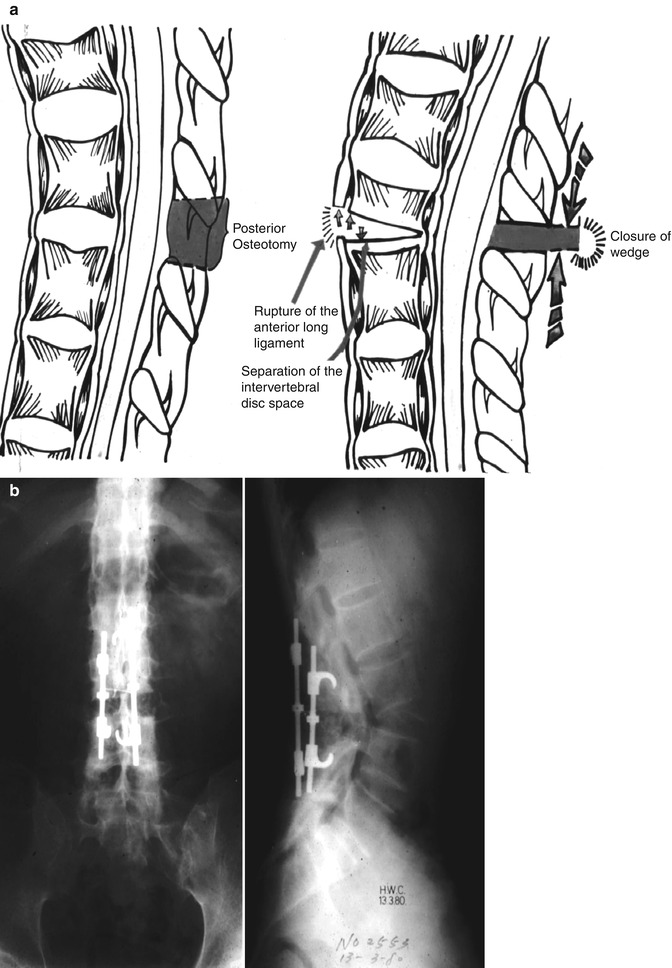

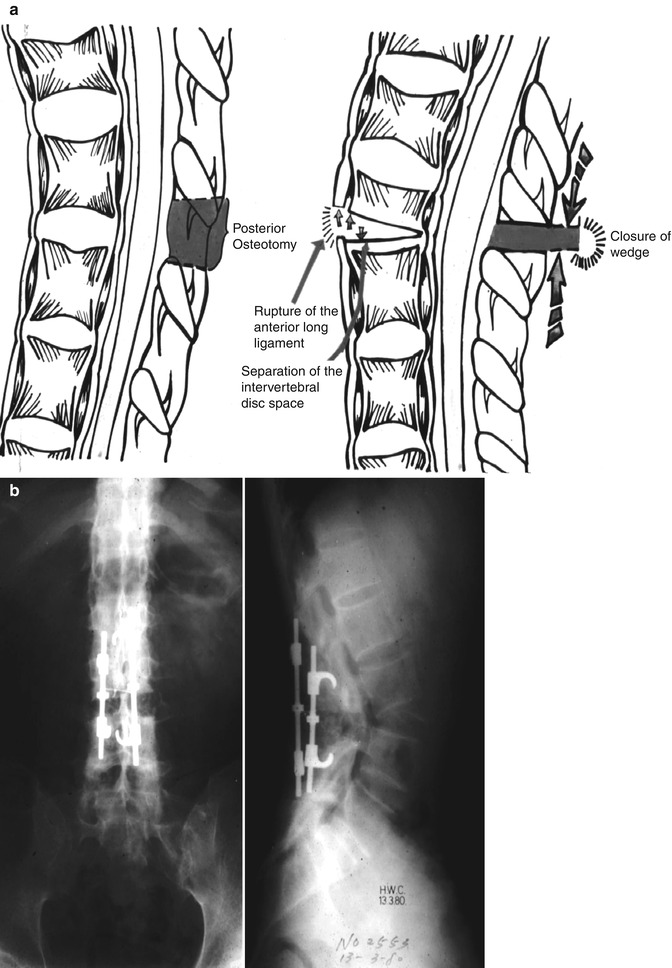

Lumbar osteotomy for lumbar kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis was pioneered by Smith-Petersen et al [1] (Fig. 6.2a, b) in 1945. He removed small wedges of posterior elements through single or multiple inverted V-shaped posterior osteotomies. The osteotomies were closed by extending the spine, which requires manipulative fracturing (rupture) of the anterior longitudinal ligament in one level and opening of the anterior aspect of the intervertebral disc space at that level. There are distinct disadvantages of this method:

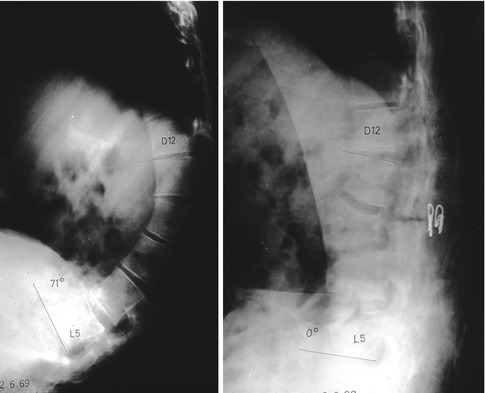

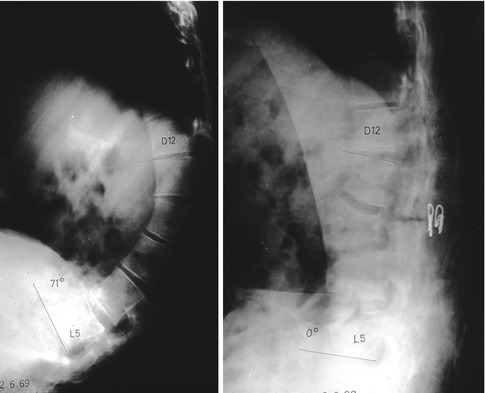

Fig. 6.2

(a) Diagrammatic representation of Smith-Petersen Osteotomy. (b) Patient with such a procedure. Note acute anterior angulation of spine

(a)

The anterior column of the spine is lengthened.

(c)

The fracturing of the anterior longitudinal ligament cannot be well controlled, and may occur at the vertebral body rather than at the preferred intervertebral disc level.

At the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, we had experimented with different types of spinal osteotomies in the 1970s to treat patients who have thoracic kyphosis with loss of the normal lumbar lordosis by the following methods. These methods had not been described in the literature before.

1.

Type 1: A posterior wedge osteotomy, followed by osteotomy of the vertebral body in front. This produces crushing of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body, whereas the anterior body surface separates. The ossified anterior ligament remains intact (Fig. 6.3).

Fig. 6.3

Type 1: posterior wedge osteotomy followed by osteotomy of vertebral body, producing crushing of the posterior aspect of body and separation of anterior body surface giving increased anterior height

2.

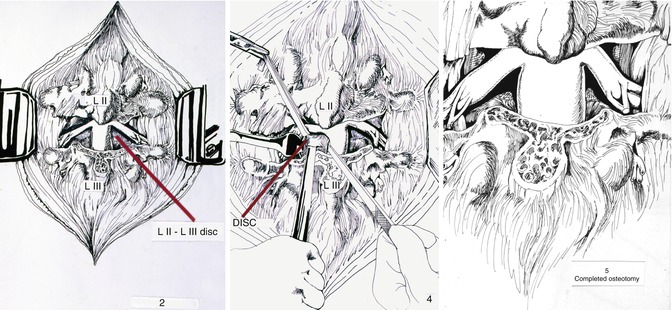

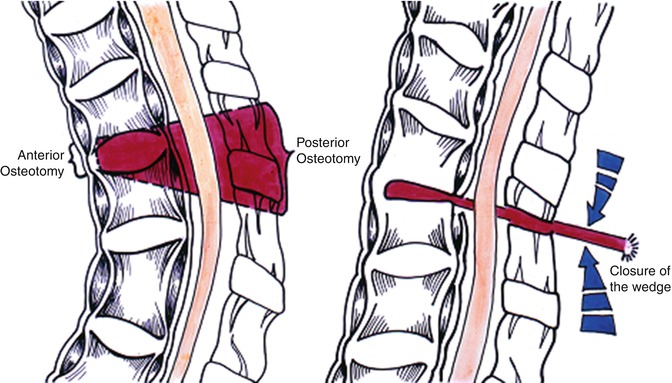

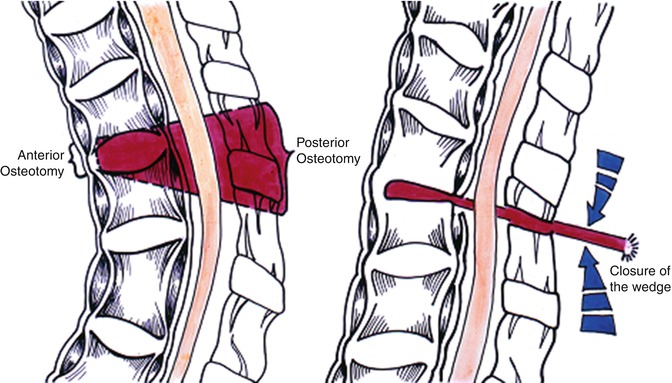

Type 2: A circumferential wedge osteotomy consisting of the intervertebral disc with its adjacent cartilage endplates and subchondral bone, and the posterior elements. The wedge is then closed (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.4

Type 2: removal of wedge including posterior elements and intervertebral disc (with end plates)

3.

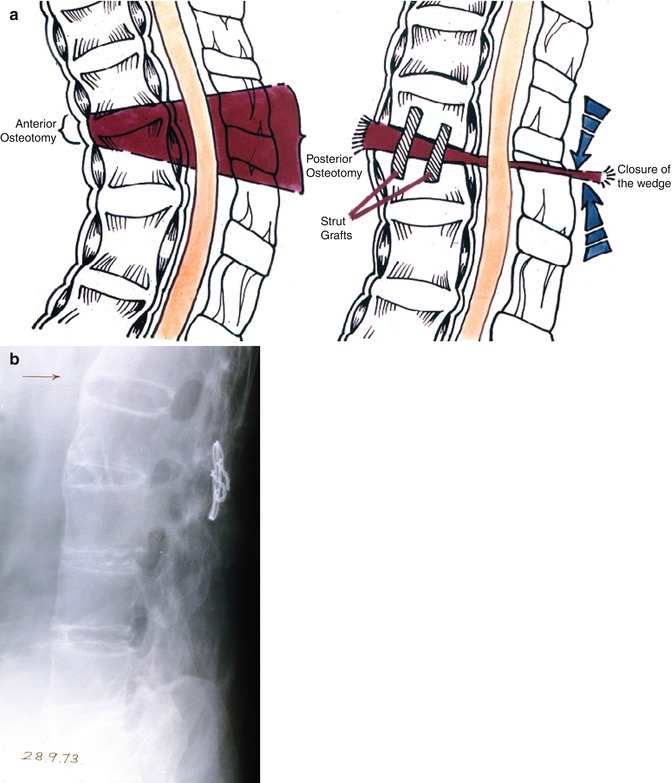

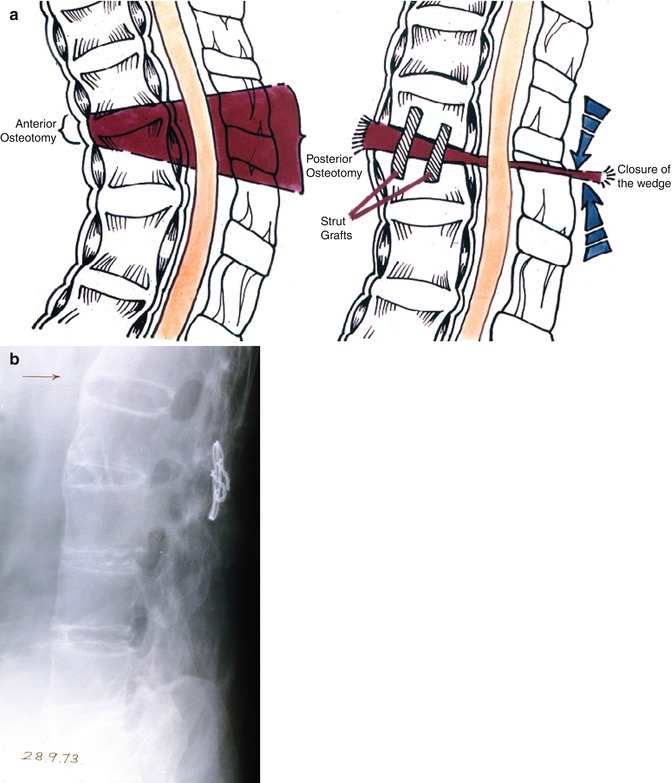

Type 3: A wedge osteotomy similar to the second method, but the disc space is opened by anterior strut grafts (Fig. 6.5a, b).

Fig. 6.5

(a) Type 3: wedge removal similar to type 2, but disc space opened by strut grafts. (b) Patient with type 3 procedure

All the procedures were done in one stage. We have used both

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

(b)

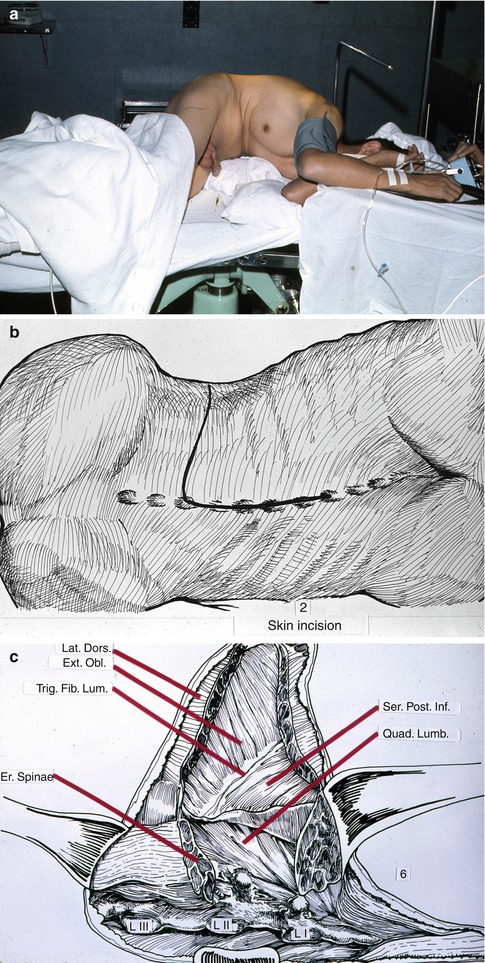

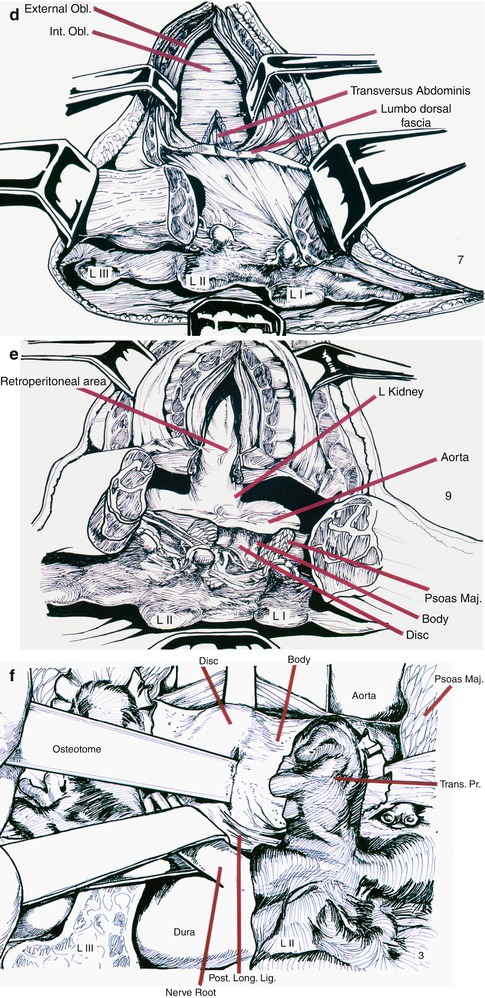

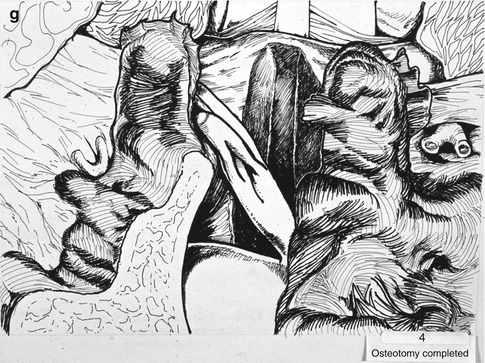

Combined anterior extraperitoneal and posterior approach. This had been used in patients who had so severe a deformity that placing the patient in the prone position will be difficult. It was also used where better visualization of the vertebral body was required for the circumferential osteotomy as described above (Fig. 6.7a–g).