and Héctor H. García3, 4

(1)

School of Medicine, Universidad Espíritu Santo, Santo, Ecuador

(2)

Department of Neurological Sciences, Hospital-Clinica Kennedy, Guayaquil, Ecuador

(3)

Cysticercosis Unit, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas, Lima, Peru

(4)

School of Sciences, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru

Abstract

The history of parasitic diseases—including taeniasis—is as old as that of humanity (Cox 2004), but it has been only in the past few centuries that enough knowledge has been accumulated to proper characterize the disease complex taeniasis/cysticercosis as a major infection of human beings (Fig. 1.1).

The history of parasitic diseases—including taeniasis—is as old as that of humanity (Cox 2004), but it has been only in the past few centuries that enough knowledge has been accumulated to proper characterize the disease complex taeniasis/cysticercosis as a major infection of human beings (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1

Timeline of major events in the history of Taenia solium taeniasis and cysticercosis

1.1 Ancient Knowledge

The Ebers Papyrus (1500 BC) includes descriptions of tapeworms and both Taenia sp. eggs, and Taenia solium cysticerci have been found in the intestine and stomach of mummies from the ancient Egypt (Bruschi et al. 2006; Le Bailly et al. 2010). Intestinal tapeworms were familiar among physicians of different ancient civilizations, who treated them with pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita pepo), a herbal medicine that it is still used nowadays (Li et al. 2012). Also, the occurrence of swine cysticercosis (measly pork) was a common knowledge among the ancient Greeks. Aristophanes (c. 448–385 BC) in his comedy “The Knights” (424 BC) has one of the slaves inspecting someone’s tongue “to see if he is measled.” Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC) in his book History of Animals described the presence of muscle bladders or cysts in pig muscles that were compared with hailstones. Interestingly, Aristotle recognized that nursing pigs do not suffer from the disease (Nieto 1982). The fact that swine was considered impure in the ancient Greece probably inclined Muhammad (570–632 AD), the Islam founder, to prohibit the consumption of pork when he wrote the Koran.

While the association between taeniasis, human cysticercosis, and epilepsy was far to be even considered in ancient times, there is some indirect evidence suggesting that cysticercus-related epilepsy may have been present in ancient Greece and Rome. The concept that epilepsy starting in adults could be related to a structural disease of the nervous system may be traced back to the Hippocratic treatise “On the Sacred Disease” (Daras et al. 2008), and there is some evidence supporting the cysticercotic origin of the epilepsy that afflicted the Roman dictator Gaius Julius Cesar (100–44 BC), as it started to happen 1 year after one of his visits to Egypt (Bruschi 2011; McLachlan 2010).

1.2 Unraveling Taenia solium

While human taeniasis and swine cysticercosis were well known in ancient civilizations, proper identification of the causal agent, and the fact that both conditions are related to the same helminth, was not recognized for centuries. Theophrastus (c. 372–287 BC) and Pliny (25–79 AD) have been credited for coining the term Taenia (from the Greek, ribbon or band). However, the name solium was used centuries later by Arnaldo de Villanueva (c. 1300 AD) to indicate that humans usually host a single tapeworm. Indeed, the denomination of Taenia solium—meaning in Latin “the lonely worm”—reflects this traditional, though erroneous, view (Del Brutto et al. 1998). There was a long-lasting confusion between the different tapeworms affecting humans, including T. saginata, T. solium, and Diphyllobothrium latum. In 1683, the discovery of the scolex by Tyson provided the first solid element for the separation of these species, and during the second half of the eighteenth century, T. solium was finally introduced into the modern zoological classification as a distinct helminth (Nieto 1982).

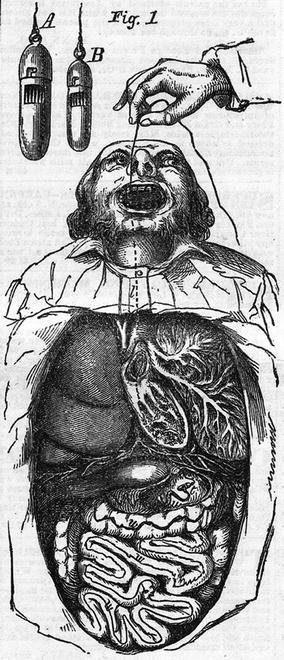

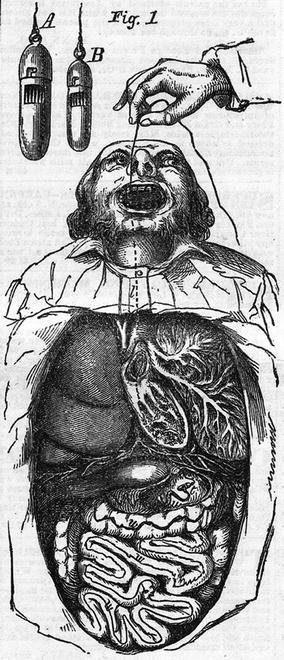

Despite this knowledge, there were a lot of inaccurate thoughts on the behavior of T. solium, like that of Alpheus Myer, an American physician who, as late as 1854, designed and patented a trap for the tapeworm (Fig. 1.2). According to his beliefs, if the patient is starved for several days, the worm will move up to the stomach looking for food and may be trapped with a device embedded in cheese that has been previously introduced into the patient’s stomach and secured with a silk thread that will be used to pull out the parasite through the mouth (de Souza 2009).

Fig. 1.2

Diagram of the Myers tapeworm trap (From de Souza N. Ingestion/The beast within). Cabinet Magazine 2009 (© Cabinet Magazine, with permission)

1.3 First Descriptions of Human Cysticercosis

Several writers concur that the first recorded case of human neurocysticercosis was probably that described by Rumler in 1558, during the autopsy of a patient with epilepsy who had liquid-filled vesicles adherent to the meninges. In the seventeenth century, Paranolus found similar vesicles in the corpus callosum of a priest who had suffered from seizures, and Wharton found cysts in the muscles of a soldier (Del Brutto et al. 1998; Nieto 1982; Wadia and Singh 2002). However, the correct parasitic nature of these vesicles was not recognized by that time, and it was Malpighi, in 1697, who described the head of the T. solium inside them. During those years, Gmelin coined the term Taenia cellulosae for the vesicles, and Zeder included them in a new genus, Cysticercus (from the Greek, bladder and tail). It was believed that cysticercus constituted a separate species of parasite, and it was classified as Cysticercus cellulosae due to its tendency to develop in connective tissue; this incorrect term is still widely used nowadays (Del Brutto et al. 1998).

1.4 Taeniasis and Cysticercosis Were Caused by the Same Parasite

The occurrence of taeniasis and neurocysticercosis in the same person was probably first recognized by the Peruvian physician, journalist, and politician Hipólito Unanue (Fig. 1.3) in 1792, as he wrote in the journal El Mercurio the case of a soldier with taeniasis who died following a generalized seizure (Deza 1987). Some years later, German pathologists confirmed the morphological similarities between the head of the adult T. solium and the scolex of cysticercus, and Küchenmeister (1855) demonstrated that oral consumption of cysticercus from pork resulted in human intestinal taeniasis by feeding convicted men with a soup containing cysticerci obtained from a recently slaughtered pig. At autopsy, Küchenmeister found “a small Taenia that was tightly attached with its proboscis to a piece of duodenal mucosa,” as well as other nine taenias, one of them with the complete crown of 22 hooklets in two rows typical of the rostellum of T. solium. The definition of the life cycle of T. solium was completed during the second half of the nineteenth century by experiments in Belgium and Germany, demonstrating that when Taenia eggs obtained from proglottids passed by infected humans were fed to pigs, the animals develop cysticercosis; failed attempts to infect other animals demonstrated that the main hosts of T. solium are humans and swine (Del Brutto et al. 1998; Nieto 1982). These findings were confirmed later by the work of Yoshino (1933a, b, c) who infected himself with T. solium cysticerci to study the life cycle of the cestode.

Fig. 1.3

(Left) Postage stamp honoring the Peruvian physician and journalist Hipólito Unanue (1755–1833), probably the first person who recognized the coexistence of Taenia solium taeniasis and neurocysticercosis in the same person, and (Right) original publication of the journal El Mercurio, dating from February 1792, where it was described such association (downloaded from http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/mercurio-peruano–18/html/027f5ec8-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_129.htm and http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/mercurio-peruano–18/html/027f5ec8-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_136.htm, last accessed April 15, 2013, documents in the open domain)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree