OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Describe the current state of HIV among underserved and vulnerable populations in the United States.

Understand the importance of testing, diagnosing, linking to and retaining in care, and managing HIV along all stages of the HIV care continuum.

Review groups at highest risk for morbidity and mortality of HIV/AIDS.

Describe challenges to patient care including patient, provider, system, and disease factors.

Identify interventions to improve HIV prevention efforts.

Identify interventions to improve care for vulnerable patients with HIV or AIDS.

INTRODUCTION

Don Sloan is a 34-year-old recently unemployed truck driver who is brought to the emergency department following an alcohol-related automobile collision. No serious traumatic injuries are found and he is medically stable. Prior to discharge he is informed of the laboratory test results, including an HIV test he had been told would be done as part of routine testing unless he refused. The emergency department attending tells him his HIV test is positive, orders a confirmatory HIV test, and refers Mr. Sloan to the outpatient HIV clinic.

Major advances in treating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have shifted HIV from a terminal illness to a manageable chronic disease. The collaborative efforts of patients, advocates, and the medical community have rapidly advanced access to highly effective treatment. Consequently, individuals who learn they are HIV infected and take antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) daily have excellent health outcomes and a low risk of passing HIV to others. Globally, however, HIV is still the world’s leading killer due to an infection.

In the United States, HIV/AIDS is still found disproportionately among people of color, especially African Americans and Latinos, men who have sex with men (MSM), injection drug users (IDUs), those with mental illness, and the poor. New infections continue to occur at alarming rates, especially among young MSM of color. Disparities in new infections and in care characterize the global epidemic as well, with gender inequity driving the growth of infections in women and girls.

This chapter reviews critical elements of prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, including strategies for improving care for vulnerable populations with a focus on populations in the United States.

THE HIV CARE CONTINUUM

The causes of HIV infection have not changed significantly since it was first reported in the early 1980s. HIV is primarily transmitted through sexual exposure, injection drug use, and less commonly through mother-to-child transmission (especially in the United States). Persons with HIV infection may be asymptomatic and unaware of their infection for many years. However, a person infected with HIV can transmit the infection from the time he or she becomes infected. Medications that effectively suppress viral load (the amount of HIV virus circulating in the bloodstream) can significantly decrease and possibly eliminate infectivity.1 Suppressing the virus therefore both treats the disease in an individual and prevents disease transmission to others.

The global community proposed a series of goals and targets to achieve a vision of zero new HIV infections, zero AIDS-related deaths, and zero discrimination in a world where people living with HIV are able to live long, healthy lives. In 2010, for the first time, the US government developed a national HIV/AIDS strategy to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic and achieve an HIV-free future. The three primary goals include reducing the number of people who become infected with HIV, increasing access to care and improving health outcomes for people living with HIV, and reducing HIV-related health disparities.2 Those working on targets for the global HIV epidemic have similar goals. United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has proposed a 90/90/90 target by 2020, in which 90% of all people living with HIV know their diagnosis, 90% are in treatment, and 90% have viral suppression. Disease modeling predicts that if these goals were achieved, by 2030 HIV would no longer be an epidemic disease.3 The World Health Organization is also focusing on key marginalized and vulnerable populations at highest risk as an essential strategy to eradicate the disease.

Although the advances in HIV diagnosis and treatment over the past few decades have been spectacular, the reality of HIV care falls far short. Nineteen million of the 35 million people infected with HIV globally do not know they are infected.3 In the United States, only 28% of persons infected with HIV have an undetectable viral load, the gold standard of HIV care.4,5 In contrast, some countries with more limited resources have achieved higher rates of viral suppression through coordinated systems of care. Critical gaps in diagnosing, linking to care, and treating persons with HIV apply across all segments of the US population, not only the underserved and vulnerable. But there is no question the gaps apply disproportionately to those who are not consistently engaged with the health-care system. Substance use disorders, mental illness, poverty, stigma, and other barriers to accessing ongoing health-care contribute substantially to less than ideal care and perpetuate continued HIV transmission.

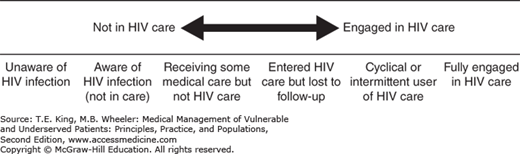

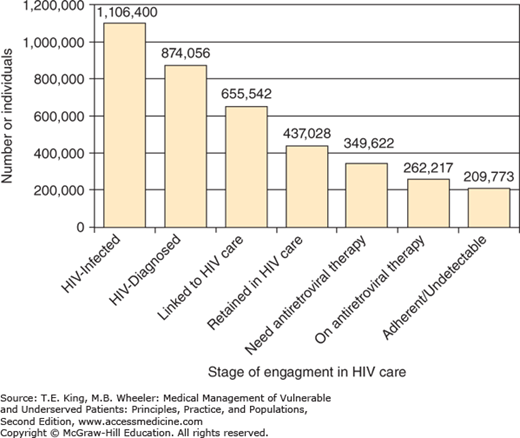

The representation of these successes and deficits in diagnosis, linkage, and retention in care and successful treatment is best described in the Gardner Cascade,4 also called the HIV care continuum (Figure 43-1). Used by health-care agencies throughout the world to monitor outcomes in HIV care initiatives, the HIV continuum recognizes that there are multiple stages during a person’s HIV diagnosis and treatment that provide opportunities and challenges to optimal care.

Figure 43-1.

The HIV Care Continuum in the United States. A: Description of the spectrum of engagement in HIV care (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA] continuum of HIV care). B: Quantification of the engagement in HIV care in the United States spanning from HIV acquisition to full engagement in care, receipt of antiretroviral therapy, and achievement of complete viral suppression. (From McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:793-800.)

The cascade defines five main steps to achieving optimal treatment: diagnosis, linkage to care, ongoing care, receipt of appropriate antiviral medications, and achieving viral suppression. At each of these stages, there is a decrement in those proceeding to the next step toward viral suppression. In the United States, only 80% of those with HIV know of their diagnosis, only 66% are linked with care, only 40% retained in care, only 30% start on ARVs, and only 28% achieve actual viral suppression. That Rwanda, Mexico, and Brazil have been able to achieve viral suppression in about 80% of those on medications proves better control is possible.3

Every interaction with clinicians, social services, community programs, and patients can be an opportunity to improve engagement in the continuum of care. Targeted interventions for persons at risk for or living with HIV/AIDS that provide housing, peer support, and culturally sensitive programs have been shown to bridge the linkage and retention gap.6 Once retained in care, most will receive antiretroviral therapy, but only a percentage of them will remain well controlled on treatment. The development of drug resistance, inconsistent access to medications, and poor adherence all contribute to lack of viral suppression.

Poor adherence in itself has a multitude of causes. For example, in some communities, HIV stigma and barriers to disclosing one’s HIV status to partners may decrease medication use. In a study reported at the 20th International AIDS Conference, providing counseling that supported disclosure within a person’s relationship led to improved adherence to medications and viral suppression rates.7

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HIV AND AIDS ALONG THE CONTINUUM OF CARE IN THE UNITED STATES

In 2011, approximately 1.2 million persons were living with HIV/AIDS in the United States, including 180,900 who were undiagnosed and unaware of their HIV infection. New infections occur in nearly 50,000 persons a year with 32,000 being diagnosed with advanced immune suppression or AIDS.8 Prevention of transmission and earlier diagnosis are imperative to achieving an HIV/AIDS-free future.

Gay, bisexual, transgender, and other MSM of all races and ethnicities remain the population most affected by HIV in the United States. The impact of HIV in the MSM population is underscored by reports that while 4% of the male population is MSM, more than 75% of new HIV infections among males were in MSM.8

Prevention of transmission in MSM is therefore key to eradicating HIV in the United States. The mainstay of prevention in this population has been sexual risk reduction. Though condom use remains key to stopping the spread of HIV in the United States, adjuvant measures such as techniques to recognize riskier situations and medications to reduce transmission are emerging. Condoms used consistently for anal sex can stop more than 70% of new HIV infections.9 While condom availability has increased significantly, access for some at-risk populations such as youth and incarcerated persons may still be a limiting factor. Many studies suggest 100% condom use is rare and rates of condom use, the most important prevention tool, are declining in this population. Fortunately, because large numbers of MSM are receiving effective antiretroviral therapy and therefore have low viral loads, transmission to their partners, even in the absence of effective barrier protection, is reduced.

Medical male circumcisions reduces the risk of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men by approximately 60% and is a key intervention globally in settings with high HIV prevalence and low male circumcision rates, but has not been shown to reduce MSM transmission.10

Home rapid testing also holds great promise for MSM. A study of high-risk MSM in New York showed that ready access to rapid test kits allowed introduction of testing to unknown partners before sexual activity, resulting in no episodes of high-risk sex with known HIV-infected partners.11

Another method of prevention is the use of postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) or a course of antiviral medication started within 72 hours after an exposure to HIV. First shown to significantly reduce HIV transmission in exposed health-care personnel, this strategy is now used for those with other exposures as well.12 In underserved communities, unfortunately, many people at risk of acquiring HIV are unaware of this method of risk reduction and may not recognize situations during which they are at high risk. Timely access to care, medication availability, cost, and adherence to the 28-day treatment course are other barriers to use of PEP in underserved patients.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is another powerful technique to prevent infection for HIV-negative persons at ongoing risk for HIV infection, MSM with multiple partners, and IDUs, for example. A daily dose of an ARV regimen in these high-risk patients may reduce the chance of acquiring HIV by up to 92%.13 Extensive counseling regarding prevention, adherence, and benefits and risks is critical, as effectiveness is closely tied to adherence.14 Treatment with a once daily single pill combination of two drugs, tenofovir and emtricitabine, should be considered for HIV-uninfected MSM, heterosexuals, and IDUs at risk for HIV infection, including those in serodiscordant relationships. Patients receiving PrEP must be HIV negative and hepatitis B status must be taken into consideration at the onset of care. Regular examinations for drug toxicity, sexually transmitted diseases, and careful surveillance for newly acquired HIV infection must follow. Daily PrEP is expensive but patient assistance programs for high deductible, low benefit, or uninsured persons are available.

The racial disparities in HIV infections continue to be glaring. Blacks account for 44% of new infections but are only 12% of the US population. Hispanic/Latino populations were diagnosed with 21% of new HIV infections, but are 16% of the population.15

The risk of HIV acquisition is higher for black MSM, despite studies reporting that they use condoms at similar rates as white MSM.16 Lack of access to care, incarceration, and selection of other black MSM as sexual partners have been demonstrated to contribute to this ongoing risk. With a higher prevalence of HIV infection in this community, the chance of HIV increases, even for those with lower risk behaviors.17

Among Latinos, MSM are also disproportionally affected. Language and immigration status may be additional barriers to linkage to care and successful treatment. A study of undocumented HIV-positive Latino immigrants in Texas found that they presented later to care than their White counterparts, though once engaged in care had similar outcomes.18

Recognition of HIV risk and disclosure of HIV status are major barriers to HIV prevention and care in minority communities. Effective prevention messaging must occur in community settings in order to reach individuals who may engage in high-risk behaviors, but do not identify as part of a high-risk group. Faith-based outreach programs that offer HIV testing in African American churches are one innovative outreach model.19 Interventions that are skill based (rather than didactic), culturally targeted, and use peers have been found to be most effective.20

Women now comprise about 20% of those diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in the United States (see Chapter 34). Black women accounted for 13% of all new HIV infections in the United States in 2010 and nearly two-thirds (64%) of all new infections among women.8

Women overwhelmingly are infected through heterosexual contact. Women often have limited knowledge about their partner’s risk factors for HIV/AIDS and often have the misperception that they are at low risk of contracting AIDS. This is especially true for minority women. Studies show that among MSM, African-American and Latino men are more likely to identify themselves as heterosexual and report having sex with women.15 Women may not feel empowered to insist on safe sex practices. Fear of emotional or physical abuse or the withdrawal of financial support, as well as substance use, prevents some women from consistently using condoms. Intimate partner violence also has been associated with increased HIV risk (see Chapter 35).21 A history of trauma and victimization is common in HIV-infected women (see Chapter 36).22 Minority women also face a number of structural factors that contribute to women’s vulnerability and place them at high risk for infection: high rates of incarceration among minority men, residential segregation and lack of medical services, and disapproval of homosexuality.

Women who desire pregnancy do not use condoms and may discover that they are infected only when they seek care for their pregnancy. Moreover, they are often unaware of measures to prevent HIV transmission despite insemination, especially sperm washing and PrEP. PrEP can be successful as a female-controlled prevention tool.14 Successful models such as the Bay Area Perinatal AIDS Center exist for counseling serodiscordant couples on risk reduction and empowering them to make healthy decisions around fertility (link: http://aidsetc.org/directory/local/bay-area-perinatal-aids-center).

Perinatal prevention of mother-to-child transmission has been the biggest success story in HIV prevention. HIV-positive women who receive successful antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy, antiretroviral medications in labor and delivery, and whose babies receive postpartum antiretroviral prophylaxis almost always have HIV-negative children. Globally, the goal of prevention of perinatal transmission seems achievable. In just 3 years, the numbers of infected women who were treated in lower- and middle-income countries jumped from 47% to 67%.23 In the United States, a large percentage of the fewer than 200 babies born with HIV annually are from racial/ethnic minority mothers.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree