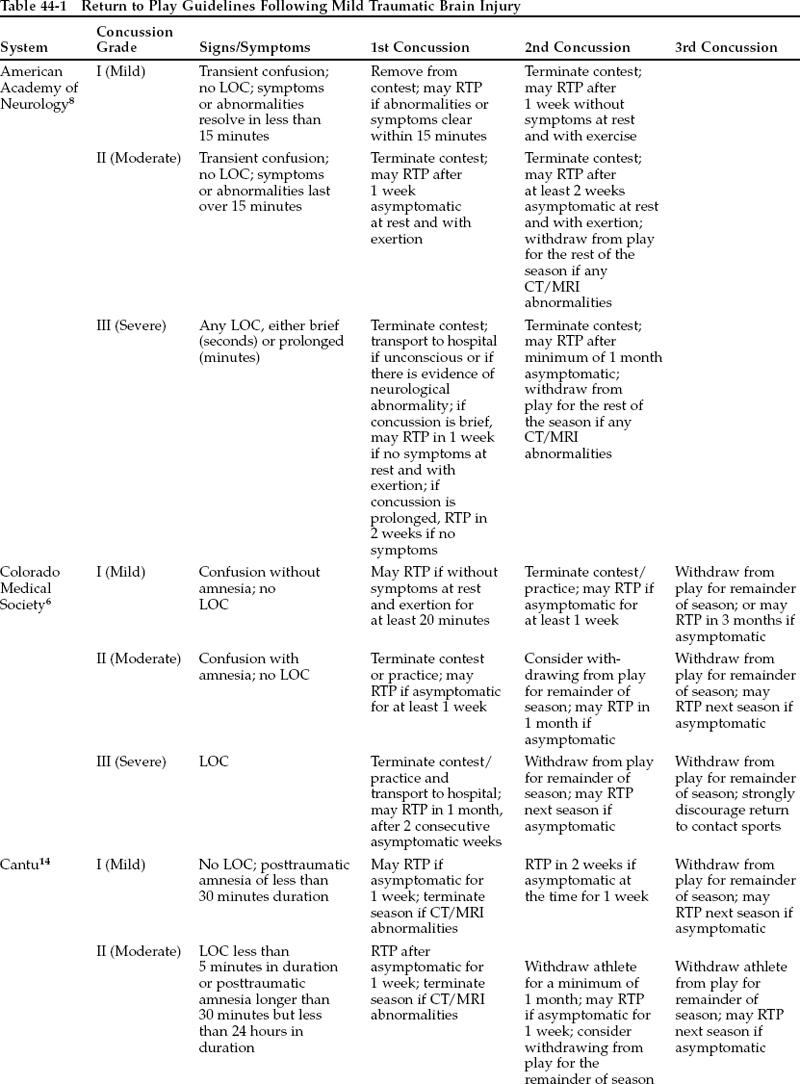

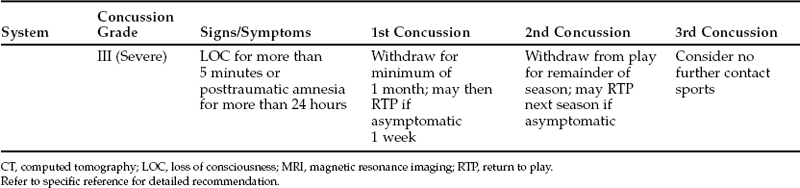

BRIEF ANSWER Currently accepted guidelines for return to play following a mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) may be classified as level III recommendations (Table 44-1). There exist only limited data comparing different return-to-play guidelines in terms of outcomes. Recommendations for return to play in athletes who have suffered life-threatening head injury (LTHI) or head injury requiring craniotomy (HIRC) are also classified as level III. Background It has been estimated that 750,000 Americans annually sustain injuries from participation in recreational activities; 82,000 (10.9%) sustain some form of head injury.1 The primary concern in these cases is the potential for an insult to the brain; when oculofacial and scalp injuries are excluded, concussion becomes the most frequently reported type of recreation-associated head injury. The annual number of sports-related concussions in the United States has been estimated to be as high as 300,000 (class III data).2 Among organized athletics in the United States, football ranks first in both the number of participants and the incidence of head injuries. Nearly 1.5 million individuals participate in contact football in the U.S. each year, and it has been variously estimated that 4 to 20% sustain an MTBI each season (class II and III data).3 Each year, a small number suffer either cumulative MTBI or serious head injury.3 Currently, there are approximately four deaths (range 0–7) annually in the U.S. from head injuries in organized football (class II data).4 At the high school level, as many as 20% of football players may suffer concussions of varying severity (class II and III data).5 Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Multiple recommendations have been made for allowing athletes to return to play after MTBI. These are based on expert opinion and on data of varying degrees of reliability. The time at which a player should be allowed to return to contact sports following a head injury depends on several factors. The severity of the injury, presence of residual neurologic deficits, and history of previous injuries must be taken into account. One problem with performing outcome studies for return-to-play guidelines is that there exists no universally accepted definition of concussion. This limitation substantially complicates the evaluation of epidemiologic data in the literature. Furthermore, MTBI may be classified according to the duration of loss of consciousness (LOC), persistence of retrograde/posttraumatic amnesia, or duration of neurologic/neuropsychological abnormalities. Numerous concussion classification schemes exist (Table 44-1). Potential issues that affect a return-to-play decision in a patient who has suffered MTBI include the risk of second impact syndrome (which is discussed in further detail below), increased vulnerability to subsequent early head injury, and the potential for long-term cumulative effects of repetitive mild injuries. It is inarguable that any athlete who remains symptomatic should be excluded from contact sports. Pearl Concussions usually (90%) occur without LOC. The signs and symptoms of concussion are often confusion and amnesia, not LOC. Life-Threatening Head Injury and Head Injury Requiring Craniotomy LTHI is defined as an injury that is acutely life-threatening, such as intracranial hemorrhage, malignant brain edema, or second impact syndrome. LTHIs characterized by lesions requiring craniotomy are described as HIRCs. In addition to the previously mentioned issues regarding return to play, several additional factors must be addressed in this population. It has been surmised that parenchymal injury may result in obliteration of the normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways through scarring. Theoretically, this could affect the brain’s buoyancy and result in a loss of cushioning effect, increasing susceptibility to subsequent injury. In patients who have had craniotomies, the craniotomy flap may also be vulnerable to recurrent bony injury, which may in turn cause additional brain injury. Literature Review Mild Traumatic Brain Injury In 1991, guidelines for return to competition were created by the Colorado Medical Society (CMS).6 These were reviewed and endorsed by several professional organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Sports Medicine, and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma.7 Partly because of a feeling among the experts that the scientific data available as a basis for constructing medical practice parameters were limited and partly because of a desire for a broader consensus of expert opinion, the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology revisited this project several years later.8,9 To aid in creating guidelines that were based more solidly on available evidence, this group reviewed the literature published from 1966 to 1996 and modified the guidelines based on these data and on a consensus of experts.8 No class I studies were available. The American Academy of Neurology guidelines were reviewed by several expert organizations, including the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, National Athletic Trainers Association, and the American Academy of Neurology Member Reviewer Network.8 Second-impact syndrome (SIS) is the most catastrophic potential sequela of an inappropriately early return to play by an athlete. It is believed to be the result of a second MTBI occurring while the athlete is still symptomatic from a previous concussion, before the brain has had a chance to recover fully from the first injury.10–12 Its etiology may be loss of autoregulation of the cerebral vasculature, with subsequent uncontrolled intracranial hypertension and cerebral edema. Although the evidence supporting the existence and occurrence of SIS is based only on case reports and expert opinion (class III), its existence has been widely accepted. Pearl

44

44

How Soon After Head Injury (With or Without Craniotomy) Can Patients Resume Contact Sports?

How Soon After Head Injury (With or Without Craniotomy) Can Patients Resume Contact Sports?

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree