16

16

How Soon Should Patients Receive Nutrition? How Much, Which Formulation, and by Which Route?

BRIEF ANSWER

Nutritional management of patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) may be important in determining overall outcome by minimizing mortality and morbidity from infectious complications, thereby allowing earlier and potentially greater neurologic improvement. As long as adequate early caloric and nitrogen intake can be achieved via enteral nutrition (EN), this is the preferred route of administration. In some patients who are unable to tolerate EN, parenteral nutrition (PN) is an acceptable means of providing support in the early postinjury phase.

Pearl

Patients with severe brain injuries exhibit metabolic responses similar to those of patients with 20 to 40% of body surface area burns.

Background

In considering appropriate nutrition for patients with TBI, one must address the timing of initiation of nutritional therapy, the route of delivery, and the formulation to be given. For brain-injured patients who are unable to eat due to depressed level of consciousness, endotracheal intubation, or alimentary tract dysfunction (depressed gag reflex, delayed gastric emptying, ileus, dysphagia), EN and PN nutrition provide excellent opportunities for temporary nutritional support. Indeed, alternative means of nutrition are necessary adjuncts to the treatment of severely brain-injured patients who experience prolonged coma and mechanical ventilation. This patient population often has concurrent major injuries of other body systems, putting them at further risk of nutritional depletion and infectious complications in the acute postinjury period.

It has long been recognized that injured patients enter hypermetabolic hypercatabolic states, suffer derangements in glucose metabolism, and experience other metabolic changes such as increased catecholamine release. However, it has only been in the past two decades that specific attention has been given to the study of nutritional and metabolic considerations in brain-injured patients. Relatively few randomized prospective studies have been done to address the optimal timing and route of nutritional support, especially with regard to neurologic outcome.

Pearl

Resting metabolic expenditure has been shown to be as high as 168%±53% of expected levels in the most severely brain-injured patients [Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 4-5].1

There has been some controversy about the ideal route of administration of nutritional formulations. Studies from the 1980s focused on differences between PN and EN with regard to their respective abilities to provide adequate caloric and nitrogen intake and positive nitrogen balance. Somewhat concurrently, techniques were evolving for various means of providing EN and for assessing nutritional status. Early investigators were also confronted with the variable use of steroid therapy in brain-injured patients. Accepted forms of treatment for elevations in intracranial pressure (ICP) have also changed over this time period. Finally, published studies on nutritional supplementation differed significantly in their design and goals. For these reasons, the results described in the existing literature can seem conflicting.

The enteral route is thought to be preferable because EN preserves mucosal integrity, minimizes bacterial translocation, and better preserves intestinal immunocompetence. However, in this patient population, gastrointestinal problems can lead to intolerance of enteral feedings, putting the patient at risk for aspiration-related pulmonary complications.2–4

Literature Review

Timing of Administration of Nutrition

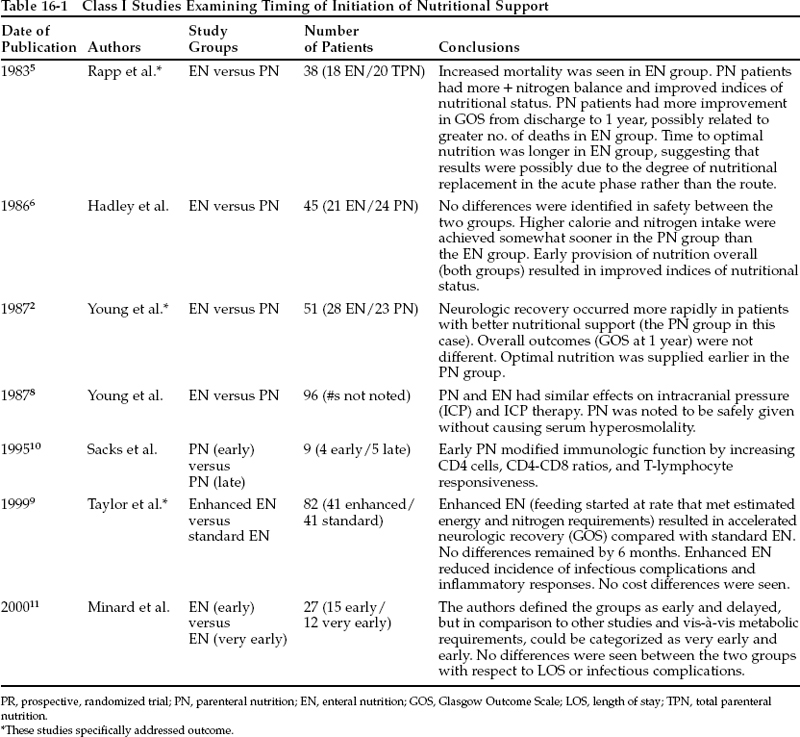

Seven prospective randomized trials have specifically addressed the issue of timing of administration of nutrition in TBI patients (Table 16-1). The majority of these studies were designed to compare routes of administration, but because of the time period necessary to achieve adequate calorie and protein intake in the enteral groups, differences in timing may be at the root of differences in results. Rapp et al5 investigated the differences between traditional delayed EN and early PN in 38 TBI patients with GCS scores of 3 to 10 (class I data). EN was begun when resumption of gastrointestinal tract function was identified. They found significant differences in peak temperature during the first 24 hours of hospitalization (higher in PN), in-hospital deaths (higher in EN), nitrogen and caloric intake (both greater in PN), and loss of triceps skinfold thickness (greater in EN). Importantly, there was notable improvement in Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score at 1 year compared with discharge for the PN group, suggesting that, by diminishing early deaths, PN provided the opportunity for improved long-term neurologic outcome. [The EN group had fewer long-term survivors (eight out of 18 patients compared with 16 out of 19 PN patients), but their outcomes as a group also improved between discharge and 1-year follow-up.] Both PN and EN groups experienced negative nitrogen balance through day 16, providing confirmation of the profound catabolic state of brain-injured patients. Other authors have reported the same finding (in class I studies).3,6,7

Young and coworkers2 (the same group of investigators) studied 51 TBI patients with GCS scores of 4 to 10 (class I data). They again demonstrated higher cumulative caloric and protein intake in a PN group compared with an EN group. EN feedings were administered via nasogastric or nasoduodenal routes. They noted no significant differences in infections or traditional tests of nutritional status in the first 2 weeks after injury. In this study, neurologic recovery occurred more rapidly in the PN group, though 1-year GOS scores were not significantly different from those of the EN group.

When these investigators looked at ICP data in 96 patients in the two treatment groups, they noted no significant differences in ICP, treatment for elevated ICP, or serum osmolality measurements (class I data).8 The latter finding is important because some have suggested that the fluid composition of PN formulas may exacerbate cerebral edema to a greater degree than EN formulas and thereby lead to ICP elevations, with resultant negative effects on outcome.

Taylor et al9 examined the effects of standard EN versus ” enhanced“ EN, in which the feedings were started at rates that approximated estimated caloric and nitrogen requirements (class I data). The standard treatment arm consisted of gradually increased enteral feedings. Each group consisted of 41 patients with severe TBI. They demonstrated fewer infectious complications, fewer overall complications, and a reduced inflammatory response (as shown by the ratio of concentrations of serum C-reactive protein to albumin) in the enhanced EN group. They also showed faster neurologic recovery in the enhanced EN group. These results lend further credence to the idea that the route of nutrition administration is not as important as the time until adequate intake is achieved, as suggested by the Rapp and Young papers.

This idea is further supported by the work of Hadley et al,6 who compared PN to EN in 45 TBI patients (mean admission GCS = 5.8) (class I data). Both routes were used early (nutritional support initiated within 48 hours), and treatment was tailored to individual needs as estimated by resting energy expenditure and indirect calorimetry measurements. No differences were discovered with respect to maintenance of serum albumin, weight loss, incidence of infection, nitrogen balance, or final outcome as assessed by GCS.

The decrease in bacterial infections seen when caloric and protein needs are met earlier in the course of treatment supports the concept that adequate nutrition promotes immunocompetence. Sacks et al10 noted that early aggressive nutritional support of TBI patients (GCS 3–12) resulted in increased CD4 cell counts, CD4/CD8 ratios, and T-lymphocyte responsiveness to certain stimuli (class I data). Their experimental groups consisted of patients given early PN at day 1 or delayed PN at day 5, and though sample sizes were small (n = 4 and 5, respectively), statistical significance was achieved for the above findings.

Minard et al11 investigated the timing of EN in two groups of TBI patients (GCS 3–11; n = 27) (class I data). Both groups were given an immune-enhancing formula via endoscopically placed nasoenteric tubes (early) or nasogastric tube after resolution of ileus (delayed). The early group had feedings initiated within 33±15 hours, and the delayed group within 84±41 hours. In view of the rapidity with which support was provided overall, these treatment arms could easily be considered as ” very early“ versus ” early“ groups, rather than ” early“ and ” delayed“ groups. For this reason, it is not surprising that no differences were seen in infectious complication rates or hospital lengths of stay between the two groups.

In summary, patients appear to have fewer infectious complications and improved outcomes when feedings are begun early in the therapeutic course. The actual route of administration may play a less important role.

Route of Nutrition

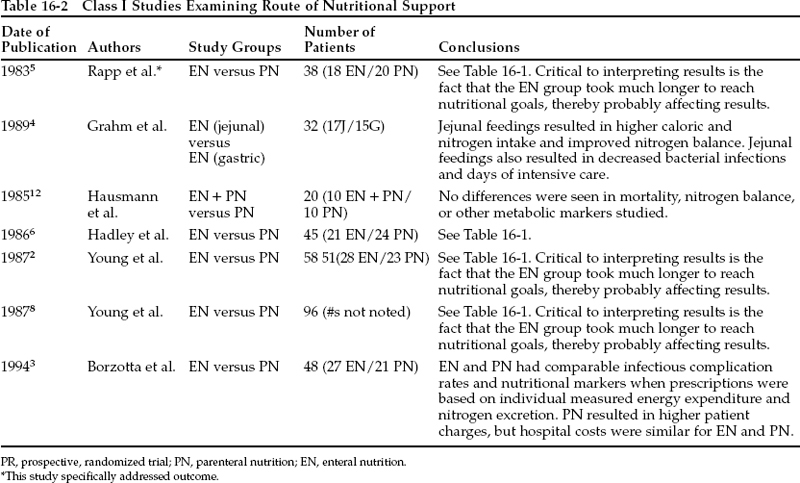

In addition to the four studies cited above, which involved differences between EN and PN, three other prospective, randomized studies of this question have been published (Table 16-2).

Thirty-two head-injured patients with GCS <10 were studied by Grahm and coworkers4 (class I data). They were able to achieve early EN via nasojejunal tubes placed with fluoroscopic guidance. Th eir EN patient group was able to receive support equal to measured resting energy expenditures within 36 hours of injury. A control group underwent gastric feeding when bowel sounds returned. Although no significant differences were seen in standard nutritional indices, the early jejunally fed group had improved daily caloric and nitrogen intake and nitrogen balance, a lower incidence of bacterial infections, and shorter intensive care unit stay.

Pearl