How to Use Medication to Manage Depression

GRAHAM J. EMSLIE

RONGRONG TAO

PAUL CROARKIN

TARYN L. MAYES

KEY POINTS

In treating depression, medications can target depressive symptoms, augument partial response, or treat associated symptoms.

Fluoxetine, citalopram, and sertraline are recommended for the initial treatment of depression, with fluoxetine having the strongest evidence.

Given the high rate of comorbidity, initiating antidepressant medication is based on the judgment that the depression is primary (meaning it is the most disabling or not a consequence of another disorder).

Response or nonresponse or adverse effects of treatment during a previous episode will influence the choice of medication for the current episode. Also, patients’ previous experience with medication will influence adherence.

Prior to initiating treatment with antidepressants, patients must be screened for suicidal behavior. Suicidality should be monitored carefully during treatment.

It is important to monitor changes in depressive symptoms using standardized forms such as the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS) rather than global judgment.

Patients are often undertreated (e.g., remain at a low dose for too long or continue on an ineffective medication with only partial improvement). An adequate trial may last up to 12 weeks because of decisions to increase the dose or initial difficulties with tolerance. A review of the treatment plan is essential if patients continue to have symptoms after 3 months of treatment.

An alternative selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is recommended as the second line of treatment (fluoxetine, citalopram, sertraline, escitalopram, or paroxetine—in adolescents only).

Although to date none of the non-SSRI drugs have been shown to be effective in acute treatment, this would not preclude use of these medications (e.g., venlafaxine, bupropion, mirtazapine, or duloxetine). At this time, these agents are generally recommended in patients who have failed to respond to adequate SSRI treatments.

Information to guide augmenting strategies in treating children and adolescents is very limited, and recommendations are generally based on adult data. Medications for augmentation include lithium, triiodothyronine (T3), bupropion, atypical antipsychotics, buspirone, and psychostimulants.

Introduction

Like many advances in medicine, discovery of antidepressants occurred serendipitously when, in 1954, Bloch and colleagues reported improved mood in patients treated with iproniazid for tuberculosis.1 Kuhn also reported decreased depressed mood with imipramine, which was being studied as a tranquilizer.2 Subsequently, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclics (TCAs) began to be used as antidepressants.

In 1973, Weinberg and colleagues presented data on diagnosis of depression in a cohort of 72 children with learning difficulties in the Journal of Pediatrics.3 In the article, he also described treatment of 19 children with antidepressants. The editor felt compelled to add, “the Editor feels it is necessary to stress extreme caution (1) in identifying any child as having a depressive illness, and (2) in prescribing any medication for such a disorder.” The editor also recommended future research directions for pediatric depression, including randomized, placebo-controlled trials.3

Over the next 20 years, research into antidepressant treatment for pediatric depression increased, but only about 250 children were involved in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) worldwide during that period. The inability to demonstrate efficacy of TCAs in pediatric populations suggested that extrapolating from adult data was problematic, so additional studies specific to children and adolescents with depression were needed. The first positive trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents (8 to 18 years of age) with MDD was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).4 In 1997, the FDA Modernization Act made it mandatory that all new compounds with potential use in the pediatric age group be studied in children and adolescents. Furthermore, the act encouraged pediatric research on medications approved for adults that were also being used in children and adolescents.5 This was followed by the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act in 2002, which established a process for studying medications in pediatric populations to improve clinical trial investigations (e.g., clinical study design, weight of evidence, ethical and labeling issues, etc.). However, even with these acts, there were problems with new pediatric data, including lack of research infrastructure and methodologic flaws in study design, and design of optimal trials was still undetermined. Regardless of these limitations, these studies have provided substantial information in the use of antidepressants in the pediatric population, with over a 200% increase in children and adolescents enrolled in RCTs in the past 10 years. Increasing data on both pharmalogic and nonpharmalogic treatments resulted in guidelines for treating depression in the pediatric population that parallel adult depression treatment.6,7,8 Contrary to these guidelines, the recommendation in European countries has been not to use antidepressants in children and adolescents except for their approved indication (only obsessive compulsive disorder) or in conjunction with psychotherapy following nonresponse to psychotherapy alone.9,10

The increased pediatric data also suggested that treatment of antidepressants caused increased suicidality (suicidal behavior and ideation), with 4% of subjects on active treatment and 2% of subjects on placebo reporting increased suicidality. There were no completed suicides in any of these trials.11 These findings resulted in an advisory from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and “black box” warnings for all antidepressants. A recent meta-analysis on antidepressant RCTs in children and adolescents, in contrast, reported that benefits outweigh risks in SSRIs and novel antidepressants.12

Based on the available empirical data, antidepressants continue to be an effective treatment for pediatric depression, and SSRIs are considered the first-line medication for this population.6,7,8 In this chapter, we review rational approaches to medication management in children and adolescents with depression. Specifically, we discuss (1) general management issues, (2) acute medication management (including dosing, pharmacokinetics, and safety), (3) use of adjunctive and augmenting agents, and (4) continuation and maintenance treatment.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

General issues to consider prior to initiating medication treatment include diagnosis, previous treatments, safety assessment, measurement of outcomes, and psychoeducation.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is based on an interview with the child and parent separately (as well as other available sources, such as teachers) to establish the presence of a current MDD episode (see Chapter 3). Currently, information on medication management is only available for MDD; however, clinicians often extrapolate from MDD data and adult data to consider medication treatment for dysthymic disorder and depressive disorder not otherwise specified. As part of the diagnostic evaluation, assessment of comorbid conditions is important. Given the high rate of comorbidity, initiating antidepressant

medication is based on the judgment that the depression is primary (in this context, meaning it is the most disabling or not a consequence of another disorder).

medication is based on the judgment that the depression is primary (in this context, meaning it is the most disabling or not a consequence of another disorder).

Because depression is an episodic disorder, assessment includes past history of the illness, as well as the phase of current treatment (if applicable). Treatment for depression involves three phases: acute, continuation, and maintenance (see Table 4.1 for definitions). Acute treatment refers to initial treatment designed to achieve response (significant reduction in depressive symptoms) and ultimately remission (minimal or no symptoms). The goal of treatment is remission, although most RCTs include response as the primary aim. Continuation treatment follows acute treatment, with the goal of preventing relapse of symptoms of the treated episode and consolidating symptom improvement for a longer duration (recovery). Continuation treatment generally lasts 4 to 9 months following remission. Maintenance treatment, which lasts 1 to 3 years, is aimed at preventing new episodes, or recurrences, of depression in participants who have recovered from their index episode.13,14,15

PREVIOUS TREATMENT

Consideration of treatment history addresses three areas: current episode, past episodes, and nonpharmacologic interventions. In evaluating patients who have already had treatment for this episode, clinicians must consider whether previous medication trials have been optimal. This involves assessing the dose administered, duration of treatment, and compliance. The Antidepressant Treatment History Form is an instrument that quantifies the adequacy of prior treatments with antidepressants. This has been used extensively in adults; however, few guidelines are available for child and adolescent patients.16 Obviously, response or nonresponse or adverse effects of treatment during a previous episode will influence medication choice for the current episode. Also, patients’ previous experience with medication will influence adherence.

Assessment of the quality and quantity of specific psychotherapy is a consideration prior to initiating medication. Specific psychotherapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) significantly reduce depression when compared with control groups (reviewed in Chapters 8 and 9). Most guidelines suggest using either a specific therapy or medication for youth who do not respond to nonspecific interventions;6,7 however, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for pediatric depression do not recommend antidepressant treatment in this age group until after specific psychotherapy has failed (and then only during ongoing psychotherapy).10 This stance is not supported by empirical data, and in fact it may be unethical to delay medication treatment for 6 to 8 weeks in severely depressed adolescents.

The current evidence suggests that options include integration of medication and psychotherapy, sequencing of treatment, or combination treatment. A trial of psychotherapy could precede a medication trial (as recommended by the NICE guidelines) or follow response to medication.17,18,19,20,21,22 Alternatively, both medication and psychotherapy could be initiated together. Data from the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) trial suggest some advantage of combined treatment;23 however, combination treatment following a brief psychosocial intervention was not superior to medication alone in a second study.24 Two smaller studies also failed to demonstrate greater efficacy with combination treatment over monotherapy in reducing depression.25,26 Sequencing of treatment can be considered depending on patient preference, severity of depression, or availability of treatments.

SAFETY ASSESSMENT

Prior to initiating medication treatments, two important areas need to be addressed: history of suicidal behavior and family psychiatric history. In the general population, studies have found that up to 5% of 14- to 18-year-olds report having suicidal thoughts.27 Another study reports that as many as 19% of teenagers (15 to 19 years of age) in the general population have suicidal ideation, and nearly 9% make an actual suicide attempt over a 12-month period.28 The rates of suicidal thinking and suicide attempts are even more frequent in youth receiving care for depression. In all, 35% to 50% of them have made, or will make, a suicide attempt.29,30 Thus assessment of suicidal thinking and behaviors (including examination of suicidal behavior versus nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior) prior to initiating treatment, as well as ongoing assessment throughout treatment, is important.31 Managing suicidal behavior during treatment is discussed in Chapter 15. In addition, the

FDA also recommended monitoring for symptoms of anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility (aggressiveness), impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania because these symptoms have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants.

FDA also recommended monitoring for symptoms of anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility (aggressiveness), impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), hypomania, and mania because these symptoms have been reported in adult and pediatric patients being treated with antidepressants.

Family history of suicides and of bipolar disorder is also important to assess. Although family history of bipolar disorder would not preclude antidepressant treatment, it would indicate that antidepressant medication should be initiated cautiously.

MEASUREMENT OF OUTCOMES

The goal of depression treatment is full remission of symptoms15 and restoration of functioning, not simply response to treatment. Implementation of evidence-based guidelines improves outcome in adults32 and children.33 However, even when following guidelines, clinicians frequently underdose or change treatment too quickly, vary substantially in visit frequency, and vary in how they assess outcome.34 Often, global judgment is used instead of specific symptom assessment, even though global judgment is less accurate.35 Severity of depression and functioning need to be assessed at baseline and throughout treatment using standardized measures. This process of measurement-based care was used successfully in real-world clinic settings in the 2006 NIMH-funded adult Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial.36

In assessing depression severity in children and adolescents, several instruments are available, including clinician-rated, self-report, and parent report. One option is the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms,37 which has a clinician, parent, and child rating, assesses all nine criteria of depressive symptoms, and correlates with the CDRS-R.38 A recent review provides details about various rating scales for depression in the pediatric age group;39 their characteristics and usefulness are also described in Chapter 3.

PSYCHOEDUCATION

As noted earlier, parents and families participate in treatment decisions. As such, they need to have sufficient information about the benefits and risks of medication treatment (as well as other treatment interventions) (see Chapter 4). A parent medication guide endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry is an excellent resource for parents (see Resources for Patients and Families). This guide includes information about depression, treatment interventions, and risks associated with antidepressant treatment, including an explanation of the “black box” warning and the concerns about suicidality with antidepressants. Although such a handout is helpful, it is equally important to review the information with families verbally, allowing adequate time to answer all their questions.

MEDICATION TREATMENT STRATEGIES

Medications for depression are used for a variety of reasons: to treat depressive symptoms, to augment in partial response, and to treat associated symptoms. Empirical evidence of medications used to treat these problems is provided later. In addition, the pharmacologic aspects of these treatments are detailed. Table 6.1 provides practical implications of the pharmacologic aspects of medications that are considered when choosing an antidepressant.

TABLE 6.1 PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF PHARMACOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF TREATMENT | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ACUTE TREATMENT

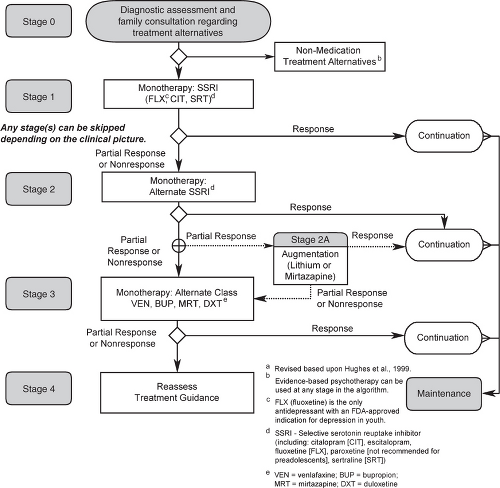

Figure 6.1 shows the updated algorithm developed for the Texas Childhood Medication Algorithm Project (CMAP) for depression.8 It is important to understand that these recommendations are a guide—not a mandate—to clinicians and are based on a synthesis of available data. Clinicians are free to deviate but, ideally, would have a good clinical reason (e.g., previous family member response, side-effect profile, opinion related to a specific profile of the patient, etc.). Data on which medications work for which patients is not yet available, and therefore clinical judgment for individual patients is critically important.

Stage 1

Based on results of published and unpublished trials, recommendations were to initiate treatment with one of three SSRIs: fluoxetine, citalopram, or sertraline, each having at least one positive RCT, with the strongest evidence for fluoxetine. Either there is inadequate data to warrant a recommendation for other SSRIs (e.g., escitalopram) or reasons to limit their use (e.g., paroxetine). Table 6.2 lists the pharmacokinetic and efficacy data for SSRIs in pediatric populations. Generally, adolescents showed greater drug/placebo differences than children in all SSRIs, with the exception of fluoxetine.12,40

TABLE 6.2 EFFICACY, PHARMACODYNAMICS, AND PHARMACOKINETICS OF SSRIs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree