Human Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunctions

17.1 Normal Sexuality

17.1 Normal Sexuality

Sexuality has always been an area of interest to the medical community. In the classical era, Hippocrates cited the clitoris as the site of female sexual arousal, the first physician historically recorded to have made that assessment. In the middle ages, Islamic physicians recommended coitus interruptus as a form of birth control. At the end of the Renaissance and the beginning of the Reformation, a linen sheath was devised as a condom, not for purposes of birth control, but as protection against syphilis. During the Victorian era, sexologists such as Havelock Ellis (Fig. 17.1-1) and Richard von Krafft-Ebing (Fig. 17.1-2) presented diverging perspectives on sexual behavior. During that same period, Sigmund Freud developed his innovative theories on libido, childhood sexuality, and the effects of the sexual impulse on human behavior. In the modern era, the research of Alfred Kinsey, the work of William Masters and Virginia Johnson, and the development of drugs that prevent contraception, aid erection, and replace hormones that decrease with menopause and aging contributed to the development of an era of sexual liberality. Sex has also been a consistent focus of curiosity and interest to humankind in general. Depictions of sexual behavior have existed from the time of prehistoric cave drawings through Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical illustrations of intercourse to current pornographic sites on the Internet.

FIGURE 17.1-1

Havelock Ellis. (Courtesy of NYU School of Medicine.)

FIGURE 17.1-2

Richard von Krafft-Ebing. (Courtesy of NYU School of Medicine.)

Sexuality is determined by anatomy, physiology, the culture in which a person lives, relationships with others, and developmental experiences throughout the life cycle. It includes the perception of being male or female and private thoughts and fantasies as well as behavior. To the average person, sexual attraction to another person and the passion and love that follow are deeply associated with feelings of intimate happiness.

Normal sexual behavior brings pleasure to oneself and one’s partner and involves stimulation of the primary sex organs including coitus; it is devoid of inappropriate feelings of guilt or anxiety and is not compulsive. Societal understanding of what defines normal sexual behavior is inconstant and varies from era to era, reflecting the cultural mores of the time.

TERMS

Sexuality and total personality are so entwined that to speak of sexuality as a separate entity is virtually impossible. The term psychosexual, therefore, is used to describe personality development and functioning as these are affected by sexuality. The term psychosexual applies to more than sexual feelings and behavior, and it is not synonymous with libido in the broad Freudian sense.

Freud’s generalization that all pleasurable impulses and activities are originally sexual has given laypersons a somewhat distorted view of sexual concepts and has presented psychiatrists with a confused picture of motivation. For example, some oral activities are directed toward obtaining food, and others are directed toward achieving sexual gratification. Both activities are pleasure seeking and use the same organ, but they are not, as Freud contended, both necessarily sexual. Labeling of all pleasure-seeking behaviors as sexual makes it impossible to specify precise motivations. Persons may also use sexual activities for gratification of nonsexual needs, such as dependency, aggression, power, and status. Although sexual and nonsexual impulses can jointly motivate behavior, the analysis of behavior depends on understanding the underlying individual motivations and their interactions.

CHILDHOOD SEXUALITY

Before Freud described the effects of childhood experiences on personalities of adults, the universality of sexual activity and sexual learning in children was unrecognized. Most sexual learning experiences in childhood occur without the parents’ knowledge, but awareness of a child’s sex does influence parental behavior. Male infants, for instance, tend to be handled more vigorously and female infants tend to be cuddled more. Fathers spend more time with their infant sons than with their daughters, and they also tend to be more aware of their sons’ adolescent concerns than of their daughters’ anxieties. Boys are more likely than girls to be physically disciplined. A child’s sex affects parental tolerance for aggression and reinforcement or extinction of activity and of intellectual, aesthetic, and athletic interests.

Observation of children reveals that genital play in infants is part of normal development. According to Harry Harlow, interaction with mothers and peers is necessary for the development of effective adult sexual behavior in monkeys, a finding that has relevance to the normal socialization of children. During a critical period in development, infants are especially susceptible to certain stimuli; later, they may be immune to these stimuli. The detailed relation of critical periods to psychosexual development has yet to be established; Freud’s stages of psychosexual development—oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital—presumably provide a broad framework.

PSYCHOSEXUAL FACTORS

Sexuality depends on four interrelated psychosexual factors: sexual identity, gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual behavior. These factors affect personality, growth, development, and functioning. Sexuality is something more than physical sex, coital or noncoital, and something less than all behaviors directed toward attaining pleasure.

Sexual Identity and Gender Identity

Sexual identity is the pattern of a person’s biological sexual characteristics: chromosomes, external genitalia, internal genitalia, hormonal composition, gonads, and secondary sex characteristics. In normal development, these characteristics form a cohesive pattern that leaves a person in no doubt about his or her sex. Gender identity is a person’s sense of maleness or femaleness. Sexual identity and gender identity are interactive. Genetic influences and hormones affect behavior, and the environment affects hormonal production and gene expression (Table 17.1-1).

Table 17.1-1

Table 17.1-1

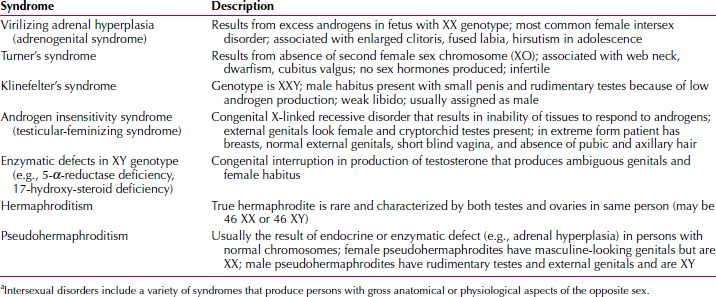

Classification of Intersexual Disordersa

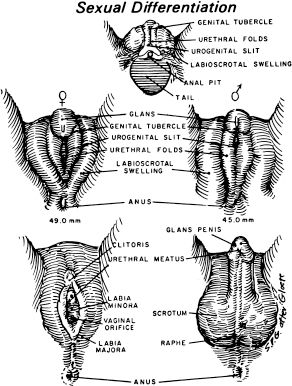

Sexual Identity. Modern embryological studies have shown that all mammalian embryos, whether genetically male (XY genotype) or genetically female (XX genotype), are anatomically female during the early stages of fetal life. Differentiation of the male from the female results from the action of fetal androgens; the action begins about the sixth week of embryonic life and is completed by the end of the third month (Fig. 17.1-3). Recent research has focused on the possible roles of key genes in fetal sexual development. A testis develops as a result of SRY and SOX9 action, and an ovary develops in the absence of such action. DAX1 plays a part in the fetal development of both sexes and WNT4 action is needed for the development of the mullerian ducts in the female fetus. Other studies have explained the effects of fetal hormones on the masculinization or feminization of the brain. In animals, prenatal hormonal stimulation of the brain is necessary for male and female reproductive and copulatory behavior. The fetus is also vulnerable to exogenously administered androgens during that period. For instance, if a pregnant woman receives sufficient exogenous androgens, her female fetus that possesses ovaries can develop external genitalia resembling those of a male fetus (Fig. 17.1-4).

FIGURE 17.1-3

Differentiation of male and female external genitalia from indifferent primordia. Male differentiation occurs only in the presence of androgenic stimulation during the first 12 weeks of fetal life.

(Redrawn from van Wyk and Grumbach, 1968; from Brobeck JR, ed. Best & Taylor’s Physiological Basis of Medical Practice. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1973, with permission.)

FIGURE 17.1-4

Twins born to a mother who received testosterone during pregnancy. Note the enlarged clitoris in each child. (Courtesy of Robert B. Greenblatt, M.D., and Virginia McNamarra, M.D.)

In the past, newborns with ambiguous genitalia were assigned their sexual identity at birth. The theory underlying this action was that parents and child would feel less confusion, and that the child would accept the assigned sex and more easily develop a stable sense of being male or female. Although this worked for some children, others developed a gender identity at odds with their assigned sex. For example, an infant designated female at birth could feel itself to be male throughout childhood, and more emphatically at puberty. In some cases, this conflict led to depression and even suicide. Current practice usually allows the child to develop with the ambiguity, which permits a sense of gender identity to evolve as the child grows. The gender identity is then more congruent with the child’s emotional sense of maleness or femaleness. Ideally, the family receives support from a medical team composed of a pediatrician, an endocrinologist, and a psychiatrist throughout this developmental process.

Gender Identity. In infants with an unambiguous sexual identity, almost everyone has a firm conviction that “I am male” or “I am female” by 2 to 3 years of age. Yet, even if maleness and femaleness develop normally, persons must still develop a sense of masculinity or femininity.

Gender identity, according to Robert Stoller, “connotes psychological aspects of behavior related to masculinity and femininity.” Stoller considers gender social and sex biological: “Most often the two are relatively congruent, that is, males tend to be manly and females womanly.” But sex and gender can develop in conflicting or even opposite ways. Gender identity results from an almost infinite series of cues derived from experiences with family members, teachers, friends, and coworkers, and from cultural phenomena. Physical characteristics derived from a person’s biological sex—such as physique, body shape, and physical dimensions—interrelate with an intricate system of stimuli, including rewards and punishment and parental gender labels, to establish gender identity.

Thus, formation of gender identity arises from parental and cultural attitudes, the infant’s external genitalia, and a genetic influence, which is physiologically active by the sixth week of fetal life. Although family, cultural, and biological influences may complicate establishment of a sense of masculinity or femininity, persons usually develop a relatively secure sense of identification with their biological sex—a stable gender identity.

GENDER ROLE. Related to, and in part derived from, gender identity is gender role behavior. John Money and Anke Ehrhardt described gender role behavior as all those things that a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of boy or man, girl or woman, respectively. A gender role is not established at birth but is built up cumulatively through (1) experiences encountered and transacted through casual and unplanned learning, (2) explicit instruction and inculcation, and (3) spontaneously putting two and two together to make sometimes four and sometimes five. The usual outcome is a congruence of gender identity and gender role. Although biological attributes are significant, the major factor in achieving the role appropriate to a person’s sex is learning.

Research on sex differences in children’s behavior reveals more psychological similarities than differences. Girls, however, are found to be less susceptible to tantrums after the age of 18 months than are boys, and boys generally are more physically and verbally aggressive than are girls from age 2 onward. Little girls and little boys are similarly active, but boys are more easily stimulated to sudden bursts of activity when they are in groups. Some researchers speculate that, although aggression is a learned behavior, male hormones may have sensitized boys’ neural organizations to absorb these lessons more easily than do girls.

Persons’ gender roles can seem to be opposed to their gender identities. Persons may identify with their own sex and yet adopt the dress, hairstyle, or other characteristics of the opposite sex. Or, they may identify with the opposite sex and yet for expediency adopt many behavioral characteristics of their own sex. A further discussion of gender issues appears in Chapter 18.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation describes the object of a person’s sexual impulses: heterosexual (opposite sex), homosexual (same sex), or bisexual (both sexes). A group of people have defined themselves as “asexual” and assert this as a positive identity. Some researchers believe this lack of attraction to any object is a manifestation of a desire disorder. Other people wish not to define their sexual orientation at all and avoid labels. Still others describe themselves as polysexual or pansexual.

Sexual Behavior

The Central Nervous System and Sexual Behavior

THE BRAIN

Cortex. The cortex is involved both in controlling sexual impulses and in processing sexual stimuli that may lead to sexual activity. In studies of young men, some areas of the brain have been found to be more active during sexual stimulation than others. These include the orbitofrontal cortex, which is involved in emotions; the left anterior cingulate cortex, which is involved in hormone control and sexual arousal; and the right caudate nucleus, whose activity is a factor in whether sexual activity follows arousal.

Limbic System. In all mammals, the limbic system is directly involved with elements of sexual functioning. Chemical or electrical stimulation of the lower part of the septum and the contiguous preoptic area, the fimbria of the hippocampus, the mammillary bodies, and the anterior thalamic nuclei have all elicited penile erections.

Studies of the brain in women have revealed that those areas activated by emotions of fear or anxiety are notably quiescent when the woman experiences an orgasm.

Brainstem. Brainstem sites exert inhibitory and excitatory control over spinal sexual reflexes. The nucleus paragigantocellularis projects directly to pelvic efferent neurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord, apparently causing them to secrete serotonin, which is known to inhibit orgasms. The lumbosacral cord also receives projections from other serotonergic nuclei in the brainstem.

Brain Neurotransmitters. Many neurotransmitters, including dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, are produced in the brain and affect sexual function. For example, an increase in dopamine is presumed to increase libido. Serotonin, produced in the upper pons and midbrain, exerts an inhibitory effect on sexual function. Oxytocin is released with orgasm and is believed to reinforce pleasurable activities.

SPINAL CORD. Sexual arousal and climax are ultimately organized at the spinal level. Sensory stimuli related to sexual function are conveyed via afferents from the pudendal, pelvic, and hypogastric nerves. Several separate experiments suggest that sexual reflexes are mediated by spinal neurons in the central gray region of the lumbosacral segments.

Physiological Responses. Sexual response is a true psychophysiological experience. Arousal is triggered by both psychological and physical stimuli; levels of tension are experienced both physiologically and emotionally; and, with orgasm, normally a subjective perception of a peak of physical reaction and release occurs along with a feeling of well-being. Psychosexual development, psychological attitudes toward sexuality, and attitudes toward one’s sexual partner are directly involved with, and affect, the physiology of human sexual response.

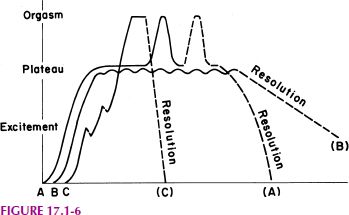

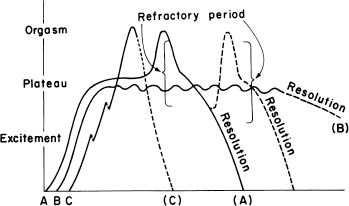

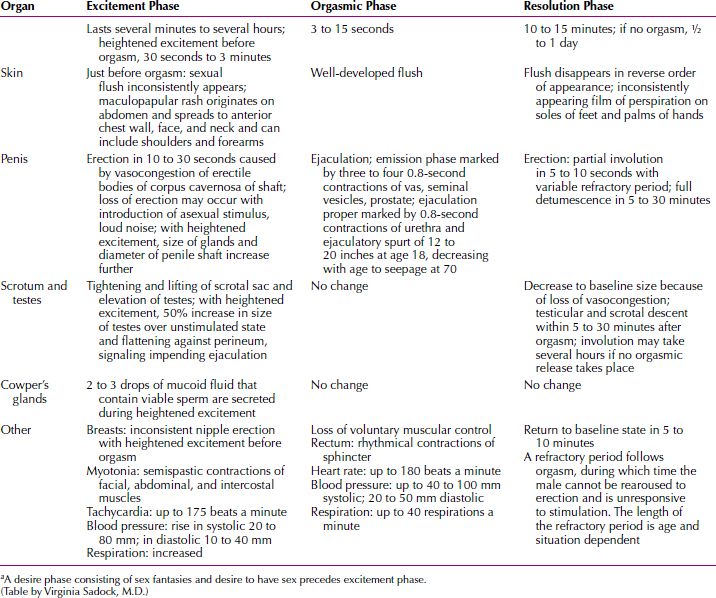

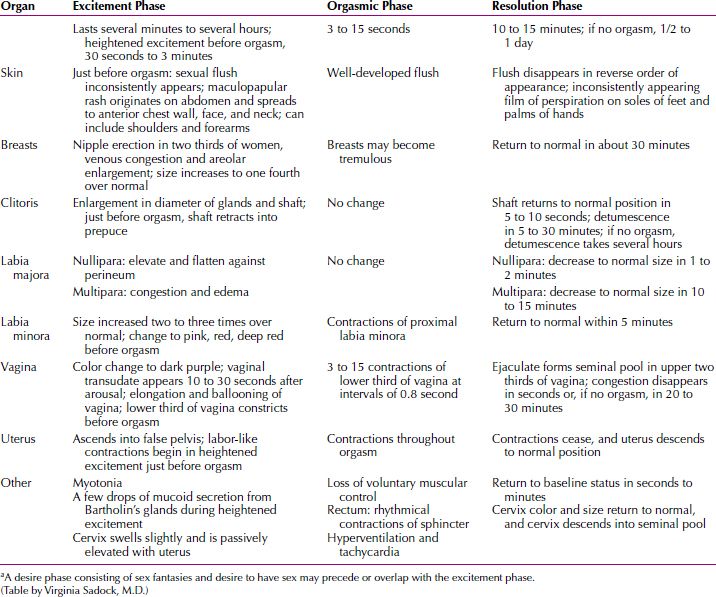

Normally, men and women experience a sequence of physiological responses to sexual stimulation. In the first detailed description of these responses, Masters and Johnson observed that the physiological process involves increasing levels of vasocongestion and myotonia (tumescence) and the subsequent release of the vascular activity and muscle tone as a result of orgasm (detumescence). Tables 17.1-2 and 17.1-3 describe the physiologic male and female sexual response cycles. It is important to remember that the sequence of responses can overlap and fluctuate. A sexual fantasy or the desire to have sex frequently precedes the physiological responses of excitement, orgasm and resolution, particularly in the male. In addition, a person’s subjective experiences are as important to sexual satisfaction as the objective physiologic response. Figures 17.1-5 and 17.1-6 illustrate several possible patterns in the phases of the male sexual response and female sexual response, respectively.

FIGURE 17.1-6

Female sexual response. An individual woman may experience any of these three patterns (A, B, or C) during a particular sexual experience. (From Walker JI, ed. Essentials of Clinical Psychiatry, Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1985:276. with permission.)

FIGURE 17.1-5

Male sexual response. An individual man may experience any of these three patterns (A, B, or C) during a particular sexual experience. (From Walker JI, ed. Essentials of Clinical Psychiatry. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1985:276, with permission.)

Table 17.1-2

Table 17.1-2

Male Sexual Response Cyclea

Table 17.1-3

Table 17.1-3

Female Sexual Response Cyclea

HORMONES AND SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

In general, substances that increase dopamine levels in the brain increase desire, whereas substances that augment serotonin decrease desire. Testosterone increases libido in both men and women, although estrogen is a key factor in the lubrication involved in female arousal and may increase sensitivity in the woman to stimulation. Recent studies indicate that estrogen is also a factor in the male sexual response and that a decrease in estrogen in the middle-aged male results in greater fat accumulation just as it does in women. Progesterone mildly depresses desire in men and women as do excessive prolactin and cortisol. Oxytocin is involved in pleasurable sensations during sex and is found in higher levels in men and women following orgasm.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN DESIRE AND EROTIC STIMULI

Sexual impulses and desire exist in men and women. In measuring desire by the frequency of spontaneous sexual thoughts, interest in participating in sexual activity, and alertness to sexual cues, males generally possess a higher baseline level of desire than do women, which may be biologically determined. Motivations for having sex, other than desire, exist in both men and women, but seem to be more varied and prevalent in women. In women they may include a wish to reinforce the pair bond, the need for a feeling of closeness, a way of preventing the man from straying, or a desire to please the partner.

Although explicit sexual fantasies are common to both sexes, the external stimuli for the fantasies frequently differ for men and women. Many men respond sexually to visual stimuli of nude or barely dressed women. Women report responding sexually to romantic stories such as a demonstrative hero whose passion for the heroine impels him toward a lifetime commitment to her. A complicating factor is that a woman’s subjective sense of arousal is not always congruent with her physiological state of arousal. Specifically, her sense of excitement may reflect a readiness to be aroused rather than physiological lubrication. Conversely, she may experience signs of arousal, including vaginal lubrication, without being aware of them. This situation rarely occurs in men.

MASTURBATION

Masturbation is usually a normal precursor of object-related sexual behavior. No other form of sexual activity has been more frequently discussed, more roundly condemned, and more universally practiced than masturbation. Research by Kinsey into the prevalence of masturbation indicated that nearly all men and three fourths of all women masturbate sometime during their lives.

Longitudinal studies of development show that sexual self-stimulation is common in infancy and childhood. Just as infants learn to explore the functions of their fingers and mouths, they learn to do the same with their genitalia. At about 15 to 19 months of age, both sexes begin genital self-stimulation. Pleasurable sensations result from any gentle touch to the genital region. Those sensations, coupled with the ordinary desire for exploration of the body, produce a normal interest in masturbatory pleasure at that time. Children also develop an increased interest in the genitalia of others—parents, children, and even animals. As youngsters acquire playmates, the curiosity about their own and others’ genitalia motivates episodes of exhibitionism or genital exploration. Such experiences, unless blocked by guilty fear, contribute to continued pleasure from sexual stimulation.

With the approach of puberty, the upsurge of sex hormones, and the development of secondary sex characteristics, sexual curiosity intensifies, and masturbation increases. Adolescents are physically capable of coitus and orgasm, but are usually inhibited by social restraints. The dual and often conflicting pressures of establishing their sexual identities and controlling their sexual impulses produce a strong physiological sexual tension in teenagers that demands release, and masturbation is a normal way to reduce sexual tensions. In general, males learn to masturbate to orgasm earlier than females and masturbate more frequently. An important emotional difference between the adolescent and the youngster of earlier years is the presence of coital fantasies during masturbation in the adolescent. These fantasies are an important adjunct to the development of sexual identity; in the comparative safety of the imagination, the adolescent learns to perform the adult sex role. This autoerotic activity is usually maintained into the young adult years, when it is normally replaced by coitus.

Couples in a sexual relationship do not abandon masturbation entirely. When coitus is unsatisfactory or is unavailable because of illness or the absence of the partner, self-stimulation often serves an adaptive purpose, combining sensual pleasure and tension release.

Kinsey reported that when women masturbate, most prefer clitoral stimulation. Masters and Johnson stated that women prefer the shaft of the clitoris to the glans because the glans is hypersensitive to intense stimulation. Most men masturbate by vigorously stroking the penile shaft and glans.

Several studies found that in men, orgasm from masturbation raised the serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) significantly. Male patients scheduled for PSA tests should be advised not to masturbate (or have coitus) for at least 7 days prior to the examination.

Moral taboos against masturbation have generated myths that masturbation causes mental illness or decreased sexual potency. No scientific evidence supports such claims. Masturbation is a psychopathological symptom only when it becomes a compulsion beyond a person’s willful control. Then, it is a symptom of emotional disturbance, not because it is sexual but because it is compulsive. Masturbation is probably a universal aspect of psychosexual development and, in most cases, it is adaptive.

COITUS

The first coitus is a rite of passage for both men and women. In the United Sates the overwhelming majority of people have experienced coitus by young adulthood, by their early 20s. In a study of persons ages 18 to 59, over 95 percent had included coitus in their last sexual interaction.

The young man experiencing intercourse for the first time is vulnerable in his pride and self-esteem. Cultural myths still perpetuate the idea that he should be able to have an erection with no, or little, stimulation, and that he should have an easy mastery over the situation, even though it is an act that he has never before experienced. Cultural pressure on the woman with her first coitus reflects remaining cultural ambivalence about her loss of virginity, despite the current era of sexual liberality. This is demonstrated in the statistic that only 50 percent of young women use contraception during their first coitus, and of that 50 percent, an even smaller number use it consistently thereafter. Young women with a history of masturbation are more likely to approach intercourse with positive anticipation and confidence.

In the last decade, coitus has also been part of the sexual repertoire of elderly adults, due to the development of sildenafil type drugs, which facilitate erections in men, and hormonally enhanced creams or hormonal pills, which counteract vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Prior to the development of these drugs, many elderly adults enjoyed gratifying sex play, exclusive of coitus.

HOMOSEXUALITY

In 1973 homosexuality was eliminated as a diagnostic category by the American Psychiatric Association, and in 1980, it was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) states: “Sexual orientation alone is not to be regarded as a disorder.” This change reflects a change in the understanding of homosexuality, which is now considered to occur with some regularity as a variant of human sexuality, not as a pathological disorder. As David Hawkins wrote, “The presence of homosexuality does not appear to be a matter of choice; the expression of it is a matter of choice.”

Definition

The term homosexuality often describes a person’s overt behavior, sexual orientation, and sense of personal or social identity. Many persons prefer to identify sexual orientation by using terms such as lesbians and gay men, rather than homosexual, which may imply pathology and etiology based on its origin as a medical term, and refer to sexual behavior with terms such as same sex and male–female. Hawkins wrote that the terms gay and lesbian refer to a combination of self-perceived identity and social identity; they reflect a person’s sense of belonging to a social group that is similarly labeled. Homophobia is a negative attitude toward, or fear of, homosexuality or homosexuals. Heterosexism is the belief that a heterosexual relationship is preferable to all others; it implies discrimination against those practicing other forms of sexuality.

Prevalence

Recent research reports rates of homosexuality in 2 to 4 percent of the population. A 1994 survey by the US Bureau of the Census concluded that the male prevalence rate for homosexuality is 2 to 3 percent. A 1989 University of Chicago study showed that less than 1 percent of both sexes are exclusively homosexual. The Alan Guttmacher Institute found in 1993 that 1 percent of men reported exclusively same-sex activity in the previous year and that 2 percent reported a lifetime history of homosexual experiences.

Some lesbians and gay men, particularly the latter, report being aware of same-sex romantic attractions before puberty. According to Kinsey’s data, about half of all prepubertal boys have had some genital experience with a male partner. These experiences are often exploratory, particularly when shared with a peer, not an adult, and typically lack a strong affective component. Most gay men recall the onset of romantic and erotic attractions to same-sex partners during early adolescence. For women, the onset of romantic feelings toward same-sex partners may also be in preadolescence, but the clear recognition of a same-sex partner preference typically occurs in middle to late adolescence or in young adulthood. More lesbians than gay men appear to have engaged in heterosexual experiences. In one study, 56 percent of lesbians had experienced heterosexual intercourse before their first genital homosexual experience, compared with 19 percent of gay men who had sampled heterosexual intercourse first. Nearly 40 percent of the lesbians had had heterosexual intercourse during the year preceding the survey.

Theoretical Issues

Psychological Factors. The determinants of homosexual behavior are enigmatic. Freud viewed homosexuality as an arrest of psychosexual development and mentioned castration fears and fears of maternal engulfment in the preoedipal phase of psychosexual development. According to psychodynamic theory, early life situations that can result in male homosexual behavior include a strong fixation on the mother; lack of effective fathering; inhibition of masculine development by the parents; fixation at, or regression to, the narcissistic stage of development; and losses when competing with brothers and sisters. Freud’s views on the causes of female homosexuality included a lack of resolution of penis envy in association with unresolved oedipal conflicts.

Freud did not consider homosexuality a mental illness. In “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality,” he wrote that homosexuality “is found in persons who exhibit no other serious deviations from normal whose efficiency is unimpaired and who are indeed distinguished by especially high intellectual development and ethical culture.” In “Letter to an American Mother,” Freud wrote, “Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual functions produced by a certain arrest of sexual development.”

New Concepts of Psychoanalytic Factors. Some psychoanalysts have advanced new psychodynamic formulations that contrast with classic psychoanalytic theory. According to Richard Isay, gay men have described same-sex fantasies that occurred when they were 3 to 5 years of age, at about the same age that heterosexuals have male–female fantasies. Isay wrote that same-sex erotic fantasies in gay men center on the father or the father surrogate.

The child’s perception of, and exposure to, these erotic feelings may account for such “atypical” behavior as greater secretiveness than other boys, self-isolation, and excessive emotionality. Some “feminine” traits may also be caused by identification with the mother or a mother surrogate. Such characteristics usually develop as a way of attracting the father’s love and attention in a manner similar to the way the heterosexual boy may pattern himself after his father to gain his mother’s attention.

The psychodynamics of homosexuality in women may be similar. The little girl does not give up her original fixation on the mother as a love object and continues to seek it in adulthood.

Biological Factors. Recent studies indicate that genetic and biological components may contribute to sexual orientation. Gay men reportedly exhibit lower levels of circulatory androgens than do heterosexual men. Prenatal hormones appear to play a role in the organization of the central nervous system: The effective presence of androgens in prenatal life is purported to contribute to a sexual orientation toward females, and a deficiency of prenatal androgens (or tissue insensitivity to them) may lead to a sexual orientation toward males. Preadolescent girls exposed to large amounts of androgens before birth are uncharacteristically aggressive, and boys exposed to excessive female hormones in utero are less athletic, less assertive, and less aggressive than other boys. Women with hyperadrenocorticalism are lesbian and bisexual in greater proportion than women in the general population.

Genetic studies have shown a higher incidence of homosexual concordance among monozygotic twins than among dizygotic twins; these results suggest a genetic predisposition, but chromosome studies have been unable to differentiate homosexuals from heterosexuals. Gay men show a familial distribution; they have more brothers who are gay than do heterosexual men. One study found that 33 of 40 pairs of gay brothers shared a genetic marker on the bottom half of the X chromosome. Another study found that a group of cells in the hypothalamus was smaller in women and in gay men than in heterosexual men. Neither of these studies has been replicated.

Sexual Behavior Patterns. The behavioral features of gay men and lesbian women are as varied as those of heterosexuals. Gay men and lesbians engage in the same sexual practices as heterosexuals, with the obvious differences imposed by anatomy.

Many ongoing relationship patterns occur among gay men and lesbians. Some same-sex pairs live in a common household in either a monogamous or a primary relationship for decades; other gay men and lesbians typically have only fleeting sexual contacts. Although many gay men form stable relationships, male–male relationships appear to be less stable and more fleeting than female–female relationships. Gay-male couples are subjected to civil and social discrimination and do not have the legal social support system of marriage or the biological capacity for childbearing that bonds some otherwise incompatible heterosexual couples. Lesbian couples appear to experience less social stigmatization and to have more enduring monogamous or primary relationships. However, opinion polls have found changes in American attitudes toward homosexuality, indicating a greater acceptance of homosexuals than in the past. This acceptance is reflected in laws in several states extending civil privileges routinely accorded to heterosexual spouses to homosexual partners, such as hospital visiting privileges or the ability to adopt children. As of 2014, eighteen states legalized marriage between homosexuals. A greater number of states recognize as legal a marriage performed in those eighteen states even if homosexual marriage is not legal in the partners’ state of residence.

Psychopathology. The range of psychopathology that may be found among distressed lesbians and gay men parallels that found among heterosexuals; some studies have reported a high suicide rate, however. Distress resulting only from conflict between gay men or lesbians and the societal value structure is not classifiable as a disorder. If the distress is sufficiently severe to warrant a diagnosis, adjustment disorder or a depressive disorder should be considered. Some gay men and lesbians with major depressive disorder may experience guilt and self-hatred that become directed toward their sexual orientation; then the desire for sexual reorientation is only a symptom of the depressive disorder.

Coming Out. According to Rochelle Klinger and Robert Cabaj, coming out is a “process by which an individual acknowledges his or her sexual orientation in the face of societal stigma and with successful resolution accepts himself or herself.” The authors wrote:

Successful coming out involves the individual accepting his or her sexual orientation and integrating it into all spheres (e.g., social, vocational, and familial). Another milestone that individuals and couples must eventually confront is the degree of disclosure of sexual orientation to the external world. Some degree of disclosure is probably necessary for successful coming out.

Difficulty negotiating coming out and disclosure is a common cause of relationship difficulties. For each person, problems resolving the coming out process can contribute to poor self-esteem caused by internalized homophobia and lead to deleterious effects on the person’s ability to function in the relationship. Conflict can also arise within a relationship when partners disagree on the degree of disclosure.

LOVE AND INTIMACY

Freud postulated that psychological health could be determined by a person’s ability to function well in two spheres, work and love. A person able to give and receive love with a minimum of fear and conflict has the capacity to develop genuinely intimate relationships with others. A desire to maintain closeness to the love object typifies being in love. Mature love is marked by the intimacy that is a special attribute of the relationship between two persons. When involved in an intimate relationship, the person actively strives for the growth and happiness of the loved person. Sex frequently acts as a catalyst in forming and maintaining intimate relationships. The quality of intimacy in a mature sexual relationship is what Rollo May called “active receiving,” in which a person, while loving, permits himself or herself to be loved. May describes the value of sexual love as an expansion of self-awareness, the experience of tenderness, an increase of self-affirmation and pride, and sometimes, at the moment of orgasm, loss of feeling of separateness. In that setting, sex and love are reciprocally enhancing and healthily fused.

Some persons experience conflicts that prevent them from fusing tender and passionate impulses. This can inhibit the expression of sexuality in a relationship, interfere with feelings of closeness to another person, and diminish a person’s sense of adequacy and self-esteem. When these problems are severe, they may prevent the formation of, or commitment to, an intimate relationship.

SEX AND THE LAW

Medicine and the law both assess the impact of sexuality on the individual and society and determine what is healthy or legal behavior. Appropriateness or legality of sexual behavior, however, is not always viewed the same way by professionals in both disciplines. The issues at the interface of sexual science and the law often are emotionally charged and reflect cultural divisions about acceptable sexual mores. They include abortion, pornography, prostitution, sex education, the treatment of sex offenders, and the right to sexual privacy, among other issues. Laws regarding these issues (e.g., criminalization of oral or anal sex by consenting adults, or the need for parental permission by minors who are requesting an abortion) vary from state to state.

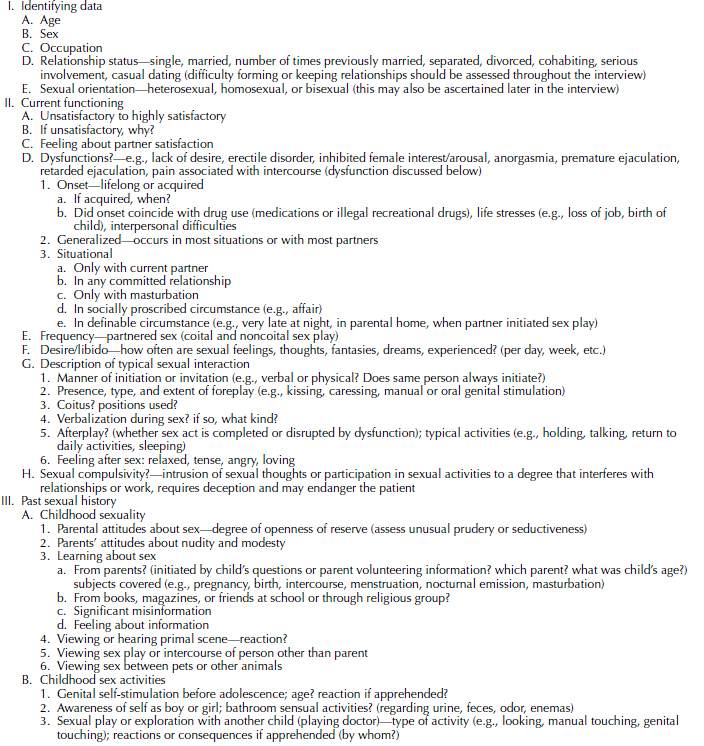

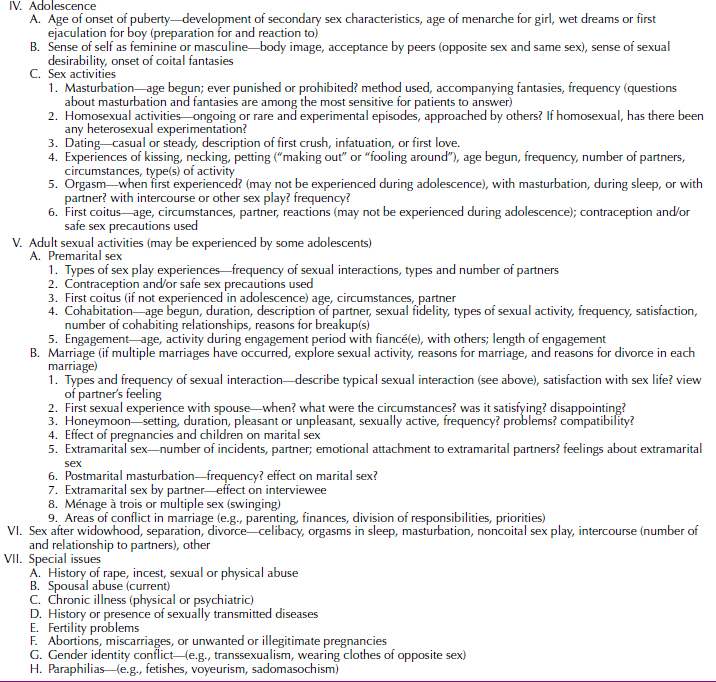

TAKING A SEX HISTORY

A sex history provides important information about patients, regardless of the presence of a sexual disorder or whether that is the patient’s chief complaint. The information can be obtained gradually, through open-ended questions. The outline in Table 17.1-4 provides a guide to the topics to be covered and a structure that can be used when time is limited.

Table 17.1-4

Table 17.1-4

Taking a Sex History

REFERENCES

Arnold P, Agate RJ, Carruth LL. Hormonal and nonhormonal mechanisms of sexual differentiation of the brain. In: Legato M, ed. Principles of Gender Specific Medicine. San Diego: Elsevier Science; 2004:84.

Bancroft J. Alfred C. Kinsey and the politics of sex research. Ann Rev Sex Res. 2004;15:1–39.

Drescher J, Stein TS, Byne WM. Homosexuality, gay and lesbian identities and homosexual behavior. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:2060.

Federman DD. Current concepts: The biology of human sex differences. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(14):1507.

Freud S. Letter to an American mother. Am J Psychiatry. 1951;102:786.

Freud S. General theory of the neuroses. In: Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 16. London: Hogarth Press; 1966:241.

Gutmann P. About confusions of the mind due to abnormal conditions to the sexual organs. Hist Psychiatry. 2006;17:107–111.

Hines M. Brain Gender. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Humphreys TP. Cognitive frameworks of virginity and first intercourse. J Sex Res. 2013;50:664–675.

Kristen PN, Kristen NJ. The mediating role of sexual and nonsexual communication between relationship and sexual satisfaction in a sample of college age heterosexual couples. J Sex Marital Ther. 2013;39:410–427

Lowenstein L, Mustafa S, Burke Y. Pregnancy and normal sexual function. Are they compatible? J Sex Med. 2013;10(3):621–622.

Melby T. Asexuality: Is it a sexual orientation? Contemporary Sexuality. 2005;39(11):1.

Patrick K, Heywood W, Simpson JM, Pitts MK, Richters J, Shelley JM, Smith AM. Demographic predictors of consistency and change in heterosexuals’ attitudes toward homosexual behavior over a two-year period. J Sex Res. 2013;50:611–619.

Person E. As the wheel turns: A centennial reflection on Freud’s three essays on the theory of sexuality. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2005;53:1257–1282.

Puppo, V. Comment on ‘New findings and concepts about the G-spot in normal and absent vagina: Precautions possibly needed for preservation of the G-spot and sexuality during surgery’. J Obstet Gynaecol Res . 2014; 40(2):639–640.

Sadock VA. Normal human sexuality and sexual dysfunctions. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:2027.

van Lankveld J. Does “normal” sexual functioning exist? INTRODUCTION. J Sex Res. 2013;50(3–4):205–206.

17.2 Sexual Dysfunctions

17.2 Sexual Dysfunctions

The essential features of sexual dysfunctions are an inability to respond to sexual stimulation, or the experience of pain during the sexual act. Dysfunction can be defined by disturbance in the subjective sense of pleasure or desire usually associated with sex, or by the objective performance. According to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), sexual dysfunction refers to a person’s inability “to participate in a sexual relationship as he or she would wish.”

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), the sexual dysfunctions include male hypoactive sexual desire disorder, female sexual interest/arousal disorder, erectile disorder, female orgasmic disorder, delayed ejaculation, premature (early) ejaculation, genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder, substance/medication induced sexual dysfunction, other specified sexual dysfunction, and unspecified sexual dysfunction. Sexual dysfunctions are diagnosed only when they are a major part of the clinical picture. If more than one dysfunction exists, they should all be diagnosed. Sexual dysfunctions can be lifelong or acquired, generalized or situational, and result from psychological factors, physiological factors, combined factors, and numerous stressors including prohibitive cultural mores, health and partner issues, and relationship conflicts. If the dysfunction is attributable entirely to a general medical condition, substance use, or adverse effects of medication, then sexual dysfunction due to a general medical condition or substance-induced sexual dysfunction is diagnosed. In DSM-5, specification of the severity of the dysfunction is indicated by noting whether the patient’s distress is mild, moderate, or severe.

Sexual dysfunctions are frequently associated with other mental disorders, such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia. In many instances, a sexual dysfunction may be diagnosed in conjunction with another psychiatric disorder. If the dysfunction is largely attributable to an underlying psychiatric disorder, only the underlying disorder should be diagnosed. Sexual dysfunctions are usually self-perpetuating, with the patients increasingly subjected to ongoing performance anxiety and a concomitant inability to experience pleasure. In relationships, the sexually functional partner often reacts with distress or anger due to feelings of deprivation or a sense that he or she is an insufficiently attractive or adequate sexual partner. In such cases, the clinician must consider whether the sexual problem preceded or arose from relationship difficulties and weigh whether a diagnosis of sexual dysfunction relevant to relationship issues is more appropriate.

DESIRE, INTEREST, AND AROUSAL DISORDERS

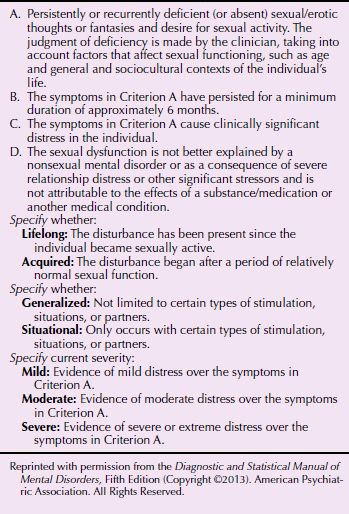

Male Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

This dysfunction is characterized by a deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity for a minimum duration of approximately 6 months (Table 17.2-1). Men for whom this is a lifelong condition have never experienced many spontaneous erotic/sexual thoughts. Minimal spontaneous sexual thinking or minimal desire for sex ahead of sexual experiences is not considered a diagnosable disorder in women, particularly if desire is triggered during the sexual encounter. The reported prevalence of low desire is greatest at the younger and older ends of the age spectrum, with only 2 percent of men ages 16 to 44 affected by this disorder. A reported 6 percent of men ages 18 to 24, and 40 percent of men ages 66 to 74, have problems with sexual desire. Some men may confuse decreased desire with decreased activity. Their erotic thoughts and fantasies are undiminished, but they no longer act on them due to health issues, unavailability of a partner, or another sexual dysfunction such as erectile disorder.

Table 17.2-1

Table 17.2-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Male Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

A variety of causative factors are associated with low sexual desire. Patients with desire problems often use inhibition of desire defensively, to protect against unconscious fears about sex. Sigmund Freud conceptualized low sexual desire as the result of inhibition during the phallic psychosexual phase of development and of unresolved oedipal conflicts. Some men, fixated at the phallic state of development, are fearful of the vagina and believe that they will be castrated if they approach it. Freud called this concept vagina dentata; he theorized that men avoid contact with the vagina when they unconsciously believe that the vagina has teeth. Lack of desire can also result from chronic stress, anxiety, or depression.

Abstinence from sex for a prolonged period sometimes results in suppression of sexual impulses. Loss of desire may also be an expression of hostility to a partner or the sign of a deteriorating relationship. The presence of desire depends on several factors: biological drive, adequate self-esteem, the ability to accept oneself as a sexual person, the availability of an appropriate partner, and a good relationship in nonsexual areas with a partner. Damage to, or absence of, any of these factors can diminish desire.

In making the diagnosis, clinicians must evaluate a patient’s age, general health, any medication regimen, and life stresses. The clinician must attempt to establish a baseline of sexual interest before the disorder began. The need for sexual contact and satisfaction varies among persons and over time in any given person. The diagnosis should not be made unless the lack of desire is a source of distress to a patient.

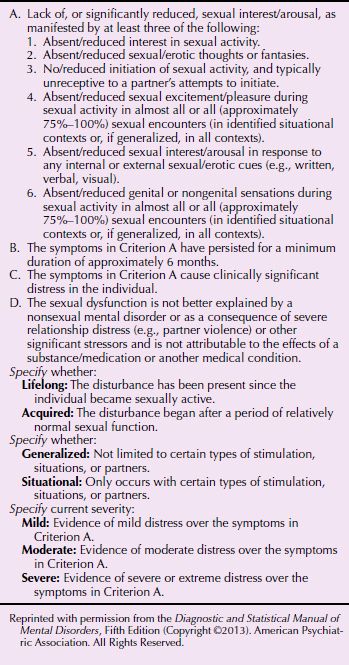

Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder

The combination of interest (or desire) and arousal into one dysfunction category reflects the recognition that women do not necessarily move stepwise from desire to arousal, but often experience desire synchronously with, or even following, beginning feelings of arousal. This is particularly true for women in long-term relationships. As a corollary, women experiencing sexual dysfunction may experience either/or both inability to feel interest or arousal, and they may often have difficulty achieving orgasm or experience pain in addition. Some may experience dysfunction across the entire range of sexual response/pleasure. Complaints in this dysfunction category present variously as a decrease or paucity of erotic feelings, thoughts, or fantasies; a decreased impulse to initiate sex; a decreased or absent receptivity to partner overtures; or an inability to respond to partner stimulation (Table 17.2-2).

Table 17.2-2

Table 17.2-2

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder

A complicating factor in this diagnosis is that a subjective sense of arousal is often poorly correlated with genital lubrication in both normal and dysfunctional women. Therefore, complaints of lack of pleasure are sufficient for this diagnosis even when vaginal lubrication and congestion are present. A woman complaining of lack of arousal may lubricate vaginally, but may not experience a subjective sense of excitement. Some studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have revealed a low correlation between brain activation in areas controlling genital response and simultaneous ratings of subjective arousal. Physiological studies of sexual dysfunctions indicate that a hormonal pattern may contribute to responsiveness in women who have arousal dysfunction. William Masters and Virginia Johnson found that women are particularly desirous of sex before the onset of the menses. Other women report feeling the greatest sexual excitement immediately after the menses or at the time of ovulation. Alterations in testosterone, estrogen, prolactin, and thyroxin levels have been implicated in female sexual arousal disorder. In addition, medications with antihistaminic or anticholinergic properties cause a decrease in vaginal lubrication.

Factors such as life stresses, aging, menopause, adequate sexual stimulation, general health, and medication regimen must be evaluated before making this diagnosis. Relationship problems are particularly relevant to acquired interest/arousal disorder. In one study of couples with markedly decreased sexual interaction, the most prevalent etiology was marital discord.

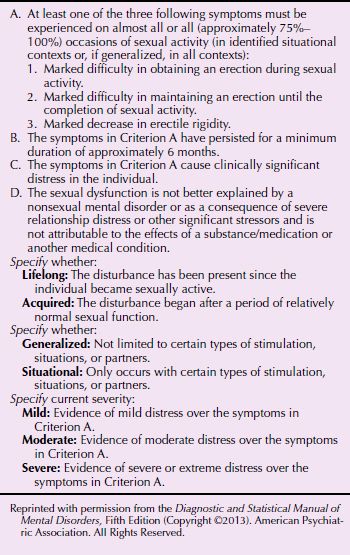

Male Erectile Disorder

Male erectile disorder was historically called impotence. The term was dropped for a more medical designation, but also because it was considered derogatory and had negative connotations for the man with the problem. However, it describes with accuracy the feelings of powerlessness, helplessness, and resultant low self-esteem men with this dysfunction frequently suffer (Table 17.2-3). A man with lifelong male erectile disorder has never been able to obtain an erection sufficient for insertion. In acquired male erectile disorder, a man has successfully achieved penetration at some time in his sexual life but is later unable to do so. In situational male erectile disorder, a man is able to have coitus in certain circumstances but not in others; for example, he may function effectively with a prostitute but be unable to have an erection when with his partner.

Table 17.2-3

Table 17.2-3

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Male Erectile Disorder

Acquired male erectile disorder has been reported in 10 to 20 percent of all men. Freud declared it common among his patients. Erectile disorder is the chief complaint of more than 50 percent of all men treated for sexual disorders. Lifelong male erectile disorder is rare; it occurs in about 1 percent of men younger than age 35. The incidence of erectile disorder increases with age. It has been reported variously as 2 to 8 percent of the young adult population. Alfred Kinsey reported that 75 percent of all men were impotent at age 80. There is a reported incidence of 40 to 50 percent in men between ages of 60 and 70. All men older than 40, Masters and Johnson claimed, have a fear of impotence, which the researchers believed reflected the masculine fear of loss of virility with advancing age. Male erectile disorder, however, is not universal in aging men; having an available sex partner is related to continuing potency, as is a history of consistent sexual activity and the absence of vascular, neurologic, or endocrine disease. Twenty percent of men fear erectile dysfunction prior to their first coitus; the reported incidence of actual erectile dysfunction during first coitus is 8 percent. As Stephen Levine has stated, the first sexual encounter “is a horse race between excitement and anxiety.”

Male erectile disorder can be organic or psychological, or a combination of both, but in young and middle-aged men the cause is usually psychological. A good history is of primary importance in determining the cause of the dysfunction. If a man reports having spontaneous erections at times when he does not plan to have intercourse, having morning erections, or having good erections with masturbation or with partners other than his usual one, the organic causes of his erectile disorder can be considered negligible, and costly diagnostic procedures can be avoided. Male erectile disorder caused by a general medical condition or a pharmacological substance is discussed later in this section.

Freud ascribed one type of erectile disorder to an inability to reconcile feelings of affection toward a woman with feelings of desire for her. Men with such conflicting feelings can function only with women whom they see as degraded (Madonna–Putana complex). Other factors that have been cited as contributing to impotence include a punitive superego, an inability to trust, and feelings of inadequacy or a sense of being undesirable as a partner. A man may be unable to express a sexual impulse because of fear, anxiety, anger, or moral prohibition. In an ongoing relationship, the disorder may reflect difficulties between the partners, particularly when a man cannot communicate his needs or his anger in a direct and constructive way. In addition, episodes of erectile disorder are reinforcing, with the man becoming increasingly anxious before each sexual encounter.

Mr. Y came for therapy after his wife complained about their lack of sexual interaction. The patient avoided sex because of his frequent erectile dysfunction and the painful feelings of inadequacy he suffered after his “failures.” He presented as an articulate, gentle, and self-blaming man.

He was faithful to his wife but masturbated frequently. His fantasies involved explicit sadistic components, including hanging and biting women. The contrast between his angry, aggressive fantasies and his loving, considerate behavior toward his wife symbolized his conflicts about his sexuality, his masculinity, and his mixed feelings about women. He was diagnosed with erectile disorder, situational type.

ORGASM DISORDERS

Female Orgasmic Disorder

Female orgasmic disorder, sometimes called inhibited female orgasm or anorgasmia, is defined as the recurrent or persistent inhibition of female orgasm, as manifested by the recurrent delay in, or absence of orgasm after a normal sexual excitement phase that a clinician judges to be adequate in focus, intensity, and duration—in short, a woman’s inability to achieve orgasm by masturbation or coitus (Table 17.2-4). Women who can achieve orgasm by one of these methods are not necessarily categorized as anorgasmic, although some sexual inhibition may be postulated. The complaint is reported by the woman, herself. However, some anorgasmic women are not distressed by the lack of climax and derive pleasure from sexual activity. In the latter instance, a woman may present with this complaint because her partner is troubled by her lack of orgasm.

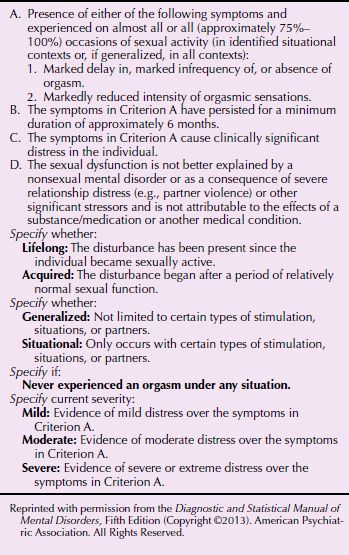

Table 17.2-4

Table 17.2-4

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Female Orgasmic Disorder

Research on the physiology of the female sexual response has shown that orgasms caused by clitoral stimulation and those caused by vaginal stimulation are physiologically identical. Freud’s theory that women must give up clitoral sensitivity for vaginal sensitivity to achieve sexual maturity is now considered misleading, but some women report that they gain a special sense of satisfaction from an orgasm precipitated by coitus. Some researchers attribute this satisfaction to the psychological feeling of closeness engendered by the act of coitus, but others maintain that the coital orgasm is a physiologically different experience. Many women achieve orgasm during coitus by a combination of manual clitoral stimulation and penile vaginal stimulation.

A woman with lifelong female orgasmic disorder has never experienced orgasm by any kind of stimulation. A woman with acquired orgasmic disorder has previously experienced at least one orgasm, regardless of the circumstances or means of stimulation, whether by masturbation or while dreaming during sleep. Studies have shown that women achieve orgasm more consistently with masturbation than with partnered sex. Kinsey found that 5 percent of married women older than age 35 years had never achieved orgasm by any means. The incidence of never having experienced orgasm is reported as 10 percent among all women. The incidence of orgasm increases with age. According to Kinsey, the first orgasm occurs during adolescence in about 50 percent of women as a result of masturbation or genital caressing with a partner; the rest usually experience orgasm as they get older. Lifelong female orgasmic disorder is more common among unmarried women than married women. Increased orgasmic potential in women older than 35 years of age has been explained on the basis of less psychological inhibition, greater sexual experience, or both.

Acquired female orgasmic disorder is a common complaint in clinical populations. One clinical treatment facility reported having about four times as many nonorgasmic women in its practice as female patients with all other sexual disorders. In another study, 46 percent of women complained of difficulty reaching orgasm. Inhibition of arousal and orgasmic problems often occur together. The overall prevalence of female orgasmic disorder from all causes is estimated to be 30 percent. A recent twin study suggests that orgasmic dysfunction in some females has a genetic basis and cannot be attributed solely to psychological differences. That study demonstrated an estimated heritability for difficulty reaching orgasm with intercourse of 34 percent and an estimated heritability in women who could not climax with masturbation of 45 percent.

Numerous psychological factors are associated with female orgasmic disorder. They include fears of impregnation, rejection by a sex partner, and damage to the vagina; hostility toward men; poor body image; and feelings of guilt about sexual impulses. Some women equate orgasm with loss of control or with aggressive, destructive, or violent impulses; their fear of these impulses may be expressed through inhibition of arousal or orgasm. Cultural expectations and social restrictions on women are also relevant. Many women have grown up to believe that sexual pleasure is not a natural entitlement for so-called decent women. Nonorgasmic women may be otherwise symptom free or may experience frustration in a variety of ways; they may have such pelvic complaints as lower abdominal pain, itching, and vaginal discharge, as well as increased tension, irritability, and fatigue.

Delayed Ejaculation

In male delayed ejaculation, sometimes called retarded ejaculation,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree