Idiopathic Myoclonic Epilepsy in Infancy

Charlotte Dravet

Federico Vigevano

Introduction

The syndrome of benign myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (BMEI) was not clearly identified before its first description in seven infants in 1981.10 These authors defined it as the occurrence of myoclonic seizures (MS) without other seizure types, except rare simple febrile seizures (FS), in the first 3 years of life in otherwise normal infants. These myoclonic seizures were easily controlled and remitted during childhood. Psychomotor development remained normal, and no severe psychological consequences were observed. Many other cases have been published since. BMEI was classified among the generalized idiopathic epilepsies in the 1989 international classification.4 Some authors have described cases with reflex myoclonic seizures, triggered by noise or contact, and have proposed to distinguish two separate entities, the second one being named “reflex myoclonic epilepsy in infancy.”24 We do not think this distinction is necessary,11 and we will describe all cases as BMEI.

As of 2006, there were 155 cases published in the literature, of which 123 corresponded to the classical description and 32 were reported as “reflex BMEI” (for a review, see Auvin et al.2 and Dravet and Bureau11). The 22 cases reported by Darra et al.6 are not counted because it is not known how many were already included in other reports. In the first description, onset was before 3 years of age, whereas in subsequent reports, some cases had a later onset, up to 4 years 8 months.17 This means that the same type of epilepsy may appear at different ages but tends to be more frequent in some periods.18 The adjective “benign” is considered problematic, because some patients do not have an actually benign evolution, particularly from the neuropsychological point of view.2,22 For this reason, the name “myoclonic epilepsy in infancy” has been proposed, but it is ambiguous. This BMEI is idiopathic, and to distinguish this syndrome from other myoclonic epilepsies, we propose replacing the benign by idiopathic. Thus, the condition should be termed “idiopathic myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (IMEI),” but, in this chapter, we continue to use BMEI, which is the designation best known to epileptologists.

General Considerations

Epidemiology

According to the few available epidemiologic data, BMEI seems to represent <1% of all epilepsies20 (unpublished data from the Centre Saint-Paul, 1999), 2% of all idiopathic generalized epilepsies (unpublished data from the Centre Saint-Paul, 1997), and around 2% of epilepsies that begin in the first 3 years of life.5

Gender Distribution

There is a prevalence of male patients, with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1.

Genetics

The genetics of BMEI are unknown. Cases are rare, and no family cases of BMEI have been described. A family history of epilepsy or FS is present in 50.5% of cases. Epilepsy types found in relatives are difficult to assess. In one case, the mother presented with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME).6 In another case, the mother had a myoclonic-astatic epilepsy (EMAS). In the case described by Arzimanoglou et al.,1 the proband was the second of two brothers, and the oldest was affected by typical EMAS. A similar situation was reported in 2006 by Darra et al.6

Personal History

Most patients do not have any relevant history prior to the onset of the myoclonic seizures. Only two (1.9%) had an associated disease: Down syndrome13 and hyperinsulinic diabetes.3 However, the occurrence of FS is not uncommon (28%). They are always simple, usually rare (one or two), and are observed before the onset of myclonus and before initiation of treatment. In one patient, two isolated nocturnal orofacial seizures occurred 6 months before appearance of myoclonic seizures.6

Clinical and Electroencephalographic Manifestations

The age at onset is usually between 4 months and 3 years; earlier onset is uncommon. Rarely, later onset, between 3 and 5 years, is reported.17,18

Initially, the myoclonic seizures are brief, often rare, and involve the upper limbs and the head, rarely the lower limbs. In infants, they may be barely noticeable, and the parents sometimes have difficulty determining their exact onset and their frequency. They often speak of “spasms” or “head nodding.” Later, the frequency increases.

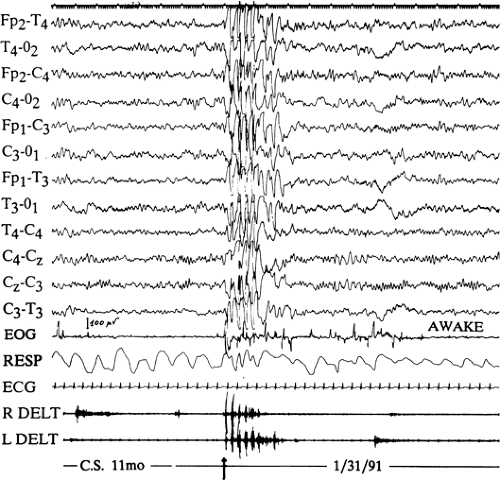

Video-electroencephalographic (EEG) and polygraphic recordings have facilitated precise analysis of these seizures. They are more or less massive myoclonic jerks, involving the axis of the body and the limbs, provoking a head drop and an upward-outward movement of the upper limbs, with

flexion of the lower limbs, and sometimes a rolling of the eyes. Their intensity varies from one child to another and from one attack to another in the same child. The most severe forms cause a sudden projection of objects held in the hands and sometimes a fall. The mildest forms provoke only brief forward movement of the head or even a simple closure of the eyes. As a rule, seizures are very brief (1–3 seconds), although they may be longer, especially in older children, consisting of pseudo-rhythmically repeated jerks lasting no more than 5 to 10 seconds. They occur several times a day at irregular and unpredictable times. Unlike infantile spasms, they do not occur in long series. They are not activated by awakening, but rather by drowsiness, except in some cases. In some patients, they can be triggered by intermittent photic stimulation (IPS). In patients with the reflex BMEI, myclonus is triggered by a sudden noise, more often by a sudden contact. The state of consciousness is difficult to assess in isolated seizures. Only when seizures are repeated is there slight impairment of consciousness without interruption of activity. In reflex myoclonic seizures, the myoclonus is elicitable both in wakefulness and in sleep, with a threshold lower in stage I and increasing gradually during the slower stages.24 No rapid eye movement (REM) sleep has been recorded and tested in patient with reflex myoclonic seizures.

flexion of the lower limbs, and sometimes a rolling of the eyes. Their intensity varies from one child to another and from one attack to another in the same child. The most severe forms cause a sudden projection of objects held in the hands and sometimes a fall. The mildest forms provoke only brief forward movement of the head or even a simple closure of the eyes. As a rule, seizures are very brief (1–3 seconds), although they may be longer, especially in older children, consisting of pseudo-rhythmically repeated jerks lasting no more than 5 to 10 seconds. They occur several times a day at irregular and unpredictable times. Unlike infantile spasms, they do not occur in long series. They are not activated by awakening, but rather by drowsiness, except in some cases. In some patients, they can be triggered by intermittent photic stimulation (IPS). In patients with the reflex BMEI, myclonus is triggered by a sudden noise, more often by a sudden contact. The state of consciousness is difficult to assess in isolated seizures. Only when seizures are repeated is there slight impairment of consciousness without interruption of activity. In reflex myoclonic seizures, the myoclonus is elicitable both in wakefulness and in sleep, with a threshold lower in stage I and increasing gradually during the slower stages.24 No rapid eye movement (REM) sleep has been recorded and tested in patient with reflex myoclonic seizures.

As development continues normally, parents and pediatricians tend not to consider these movements as pathologic events.

When an EEG is performed, it can be normal during the awake state if no myoclonic fits are recorded.

However, myoclonias are always associated with an EEG discharge. Polygraphic recordings demonstrate that myclonic are accompanied by a discharge of fast generalized spike-waves (SW) or polyspike-waves (PSW) at >3 Hz, lasting for the same time as the myoclonia (Figs. 1 and 2). This discharge is more or less regular and can start in the two frontal areas and the vertex. Myoclonias are brief (1–3 seconds) and usually isolated. Each myoclonic jerk may be followed by a brief loss of time. Sometimes, after the attack, there is a voluntary movement, visible as a normal muscular contraction. In only one patient did we observe the association of myclonus in the deltoid muscle with pure atonia in the neck muscles. During drowsiness, there is enhancement of the myclonic jerks; they usually, but not always, disappear during slow sleep. The myoclonic seizures triggered by tactile and acoustic stimuli have the same characteristics (Fig. 2). Ricci et al.24 noted that the initial manifestation generally, but not always, consisted of a blink, followed 40 to 80 msec later by the first myoclonic arm jerk. After a myoclonic attack, there was a refractory period, lasting 20 to 30 seconds to 1 to 2 minutes, during which sudden stimuli did not provoke attacks, even when the startle reaction was easily elicitable. IPS can also provoke myoclonic seizures.

The interictal EEG is normal. Spontaneous SW discharges are rare; some slow waves may be found over the central areas. Darra et al.6 described rhythmic, 4- to 5-Hz theta activity over the rolandic regions and the vertex in 4 of 22 children. IPS does not provoke SW without concomitant myclonus at the onset. Nap sleep recordings have shown a normal organization of sleep; generalized SW discharges may occur during REM sleep.

Evolution and Treatment

No other type of seizure is observed in children with BMEI, even if they are left untreated (for up to 8.5 years in one of our patients). In particular absence or tonic seizures do not

occur. Clinical examination is normal. Interictal myoclonus was described only by Giovanardi-Rossi et al.,17 in 6 patients. In reviewing our patients, we found mild interictal myoclonus in 2 patients, revealed by polygraphic recordings. Many patients were not investigated, but when computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed, they were normal (46 patients).

occur. Clinical examination is normal. Interictal myoclonus was described only by Giovanardi-Rossi et al.,17 in 6 patients. In reviewing our patients, we found mild interictal myoclonus in 2 patients, revealed by polygraphic recordings. Many patients were not investigated, but when computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed, they were normal (46 patients).

The outcome seems to depend on an early diagnosis and treatment. Myoclonic jerks are easily controlled by valproate (VPA), and the child may then develop normally. If left untreated, patients continues to experience myoclonic attacks, and this may lead to impaired psychomotor development and behavioral disturbances.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree