OBJECTIVES

Review health issues faced by immigrants.

Discuss a framework for understanding the health risks of immigrants.

Describe demographics and other characteristics of immigrants to the United States.

Review determinants of legal immigrant status in the United States.

Discuss interventions to improve care.

Review patient, provider, and system challenges in the care of immigrants.

INTRODUCTION

Mr. Moraga fled political persecution in Guatemala. He is undocumented, speaks little English, and has been working as a janitor. Many people assume, because he is undocumented, poor, and Latino, that he is also uneducated. He holds a PhD.

Multiple waves of immigration, including the prolonged importation of African slaves, account for the fact that 99% of all US residents are either immigrants or their descendants. Immigrants everywhere in the world are a diverse group, differing in everything from their backgrounds to reasons for immigration. People have migrated to the United States, as they have other places in the world, searching for economic and educational opportunity and fleeing religious persecution, political and social unrest, and personal danger. Consequently, political, economic, geographic, and cultural stimuli and barriers to immigration have shaped the character and experiences of immigrant communities in the United States and globally. Immigrants face increased risks of many illnesses, poor health-care access, and lower-quality health. This chapter reviews these risks and the ways to help mitigate them.

IMMIGRATION: DEMOGRAPHICS

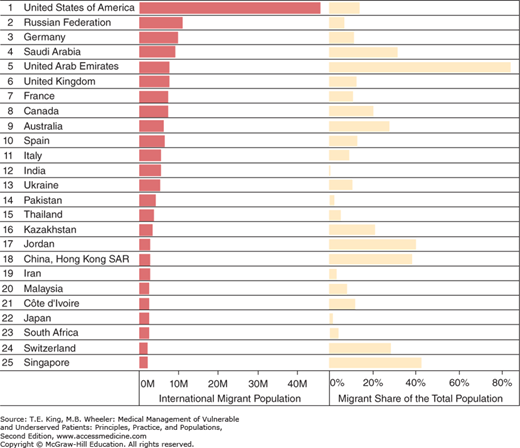

Immigration is defined as resettlement in a country to which one is not native. Immigration is a potent global force (Figure 29-1).1 Indeed, according to the US census, in 2010 almost 13% of the population was foreign born (Table 29-1).2

Figure 29-1.

Top 25 destination countries, 2013: International migrant population and migrant share of total population. Source: Migration Policy Institute tabulation of data from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2013). Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2013 revision (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2013). Available at http://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/international-migration-statistics.

| Region of Birth | Population | Margin of Errora (±) | Percent | Margin of Errora (±) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalb | 39,956 | 115 | 100.0 | (X) |

| Africa | 1607 | 33 | 4.0 | 0.1 |

| Asia | 11,284 | 47 | 28.2 | 0.1 |

| Europe | 4817 | 44 | 12.1 | 0.1 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 21,224 | 90 | 53.1 | 0.1 |

| Mexico | 11,711 | 83 | 29.3 | 0.2 |

| Other Central America | 3053 | 46 | 7.6 | 0.1 |

| South America | 2730 | 42 | 6.8 | 0.1 |

| Caribbean | 3731 | 42 | 9.3 | 0.1 |

| Northern America | 807 | 16 | 2.0 | – |

| Oceania | 217 | 10 | 0.5 | – |

Immigration into the US during the 1990s reached a historic high, with approximately 1 million persons entering the United States legally per year. Immigration rates have remained high, with one-third of all foreign-born residents arriving in the United States after 2000. All told, there are about 11.7 million undocumented immigrants in the United States.3 In contrast, the number of refugees (i.e., somebody who is seeking or taking refuge, especially from war or persecution, by going to a foreign country) entering the United States has been going up very slowly despite burgeoning numbers of refugees globally.4

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE IMMIGRATION EXPERIENCE

Mrs. Rosas left her children with her mother when she immigrated to the United States. Eventually, her mother and the children are able to come to visit on a tourist visa. While in the United States, her mother suffers a debilitating stroke.

Although recent immigrants have always been a large part of the US population, in the past most came from Europe. Today’s immigrants are increasingly diverse, coming mostly from Latin America and Asia. Latin Americans make up 53% of the foreign born, Asians 28%, and Europeans 12%, with the remaining from other regions (link to maps of where immigrants to the United States come from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/09/28/from-ireland-to-germany-to-italy-to-mexico-how-americas-source-of-immigrants-has-changed-in-the-states-1850-to-2013/). These categories are so broad that they hide a rich diversity of nationalities, ethnicities, cultures, languages, migration histories, socioeconomic classes, and racial admixtures.5 This diversity of factors, however, profoundly affects people’s experience of immigration and the characters of the communities they form. These communities change with each wave of immigration and each generation of children.

Reviewing a patient’s immigration history may help the clinician understand their patients’ experience and its possible impact on health. These experiences, as in the case of Mrs. Rosas’ family, may be very different for each member. Where someone comes from, the reason for migration, whether they come alone or with family, who and what are left behind, and whether they join an immigrant community are all important. Age, culture, language, education, and legal status are also significant factors to consider (see “Core Competency”).

IMPACT OF IMMIGRANTS’ LEGAL STATUS

A person’s documentation status has a profound effect on access to opportunities and services that affect health. Inquiring about a patient’s legal status can help clinicians understand the services their patients are entitled to and the hurdles they must face in everyday life, but must be done with sensitivity. Some patients question the clinician’s motives, fearing denial of care, or, even worse, that the health-care provider might turn them into the immigration service. In addition, access issues are complicated when the US-born children of undocumented immigrants are granted citizenship. For example, restricted parental access to public benefits might prevent undocumented parents from seeking help for their legally entitled children.

Legal immigrants are those who have obtained citizenship, have permanent residency status (possess a green card), temporary residency status (are part of an amnesty program), have been granted temporary protected status because of a natural disaster or civil conflict in their country, or are asylees or refugees.

Asylees are those who have been granted political asylum from fear of prosecution once they have already entered the United States, and they are typically eligible for citizenship within a year.

Refugees, on the other hand, apply to come to the United States from a country to which they have fled, fearing persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion in their own country.6 After a year of entering the United States, refugees are eligible for permanent resident status and after 5 years for citizenship. Victims of “severe trafficking,” that is, those coerced into sexual or other servitude, are also eligible for refugee status.

Nonimmigrant foreign nationals are those here on visas allowing them to work or study. They must demonstrate an ability to support themselves and claim they do not intend to stay in the United States permanently.

IMPACT OF IMMIGRATION POLICIES

Immigration issues have always been controversial: who and how people are allowed to enter legally, the causes and consequences of entering illegally, and who is eligible for refugee status are political matters. National policies determine who is legally allowed to enter the country and have a powerful influence on their experiences once here.

Before 1980, US refugee policy was heavily influenced by the Cold War. Leaving a communist state was usually sufficient justification for refugee eligibility. The Refugee Act of 1980 based refugee status less on ideology and more on evidence of persecution. Nevertheless, the president can make exceptions to the definition and allow easier access for some. The president and Congress determine the total number of refugees who may be admitted to the United States each year from each of five regions, with separate quotas for each.

The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act significantly tightened border restrictions, changed rules on asylum, and restricted immigrant access to public benefits, including for legal immigrants.7 This act also legislated specific vaccination and medical examination requirements for immigrants and those seeking permanent residency status. Physicians certified as Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (BCIS) Designated Civil Surgeons must perform these examinations.

IMPACT OF EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES

Many of those coming to this country, legally and illegally, have come to work. Indeed, new immigrants formed about 50% of the new labor force growth in the country in the last decades, and are thought to have provided a net economic gain for the US economy and for nonimmigrant workers. Approximately 26 million immigrants are in the labor force, accounting for 16% of the civilian workforce in 2014. This represents threefold increase since 1970. As in all other domains, the work immigrants do is very diverse. Thirty percent of immigrants worked in professional or managerial occupations; 25% percent in service occupations; and 30% in transportation, production, natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations.8 Twenty-five percent of all physicians,9 27% of science and engineering professionals,10 and 72% of all farm workers in the United States are foreign born.11 Work in agriculture, meat packing, restaurant industry, and construction, particularly if the worker is undocumented, often places many immigrants at high risk for occupational injury and illness (see Chapter 25).

IMPACT OF OTHER SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS

The diversity of immigrants is so great that it is impossible to generalize from population statistics to any one individual. The United States attracts both highly educated and wealthy immigrants, and those who have had few educational or economic opportunities in their own countries. Statistically speaking, immigrants are more likely to be employed, reside in larger multigenerational households, have more children, live in poverty, and lack a high school diploma than native-born Americans. Revealing the diversity of this population, immigrants are also more likely to have a PhD than native-born Americans.10 Immigrants without a high school diploma from their native lands are especially likely to have severely poor literacy in English.9

ISSUES AFFECTING HEALTH-CARE ACCESS AND DELIVERY

There is a misperception that immigrants overburden the health-care system.10 Immigrants use public resources at lower rates than native-born populations and have significantly poorer access to health care. For example, prior to health-care reform, 34% of immigrants lacked health insurance, whereas only 12% of native-born US residents were uninsured.5 Noncitizens receive much lower rates of medical and dental care, and go the emergency room less often. Noncitizen children in non–English-speaking families were much less likely to see a doctor than children who are English-speaking citizens.12 When they do access medical care, immigrants are also at risk of receiving inadequate care.12,13,14,15,16 Moreover, it is an underappreciated fact that immigrants, including unauthorized immigrants, contribute significantly to tax revenues supporting services that they often do not use.16,17

The cultural diversity of immigrants may affect health-care delivery. Immigrants may have culturally based health beliefs that may affect trust and adherence to provider recommendations (see Chapter 14). As with all patients, it is important for the health-care providers to understand the immigrant patient’s spiritual beliefs. Immigrants come from many different religious backgrounds, and religious communities are important sources of emotional and social support. Religious values influence health beliefs and values, for example, about modesty, reproductive and sexual matters, and end-of-life care. For example, Muslim women may prefer a female provider, and in fact be unwilling to be examined by a male provider.

Immigrant patients often use alternative or complementary medications, although they may be uncomfortable about revealing this to providers. Latinos are more likely than other ethnic groups to use alternative methods because they are cheaper.18 Use of home remedies, expectations of medical treatment, and health-care delivery also are often based on patients’ experiences in their home countries. For example, some immigrants may expect parenteral treatments such as injections to be administered.

In many countries, medications may be obtained without a prescription, even those considered dangerous or banned in the United States. Medications may be outdated or adulterated. In one study of Asian patent medications available in California, 32% were found to have unlabeled medications, 14% mercury, 14% arsenic, and 10% lead.19 Immigrants residing in the United States may use some of these medications.20

Immigrants may be wary of the health-care system and its personnel. They may fear being asked about their documentation status, being misunderstood (particularly if they do not speak English), not being able to pay for care, or outright discrimination. Studies have shown that minority patients are less likely to find doctors and health systems trustworthy than white patients. Minority patients report feeling they would receive better care if they were of a different race or ethnicity, feeling they are treated with disrespect, looked down on, and that their providers do not understand their cultural origins and beliefs.21 Not being able to speak the same language as the health-care provider is also an important impediment to both trust and the receipt of high-quality medical care (see Chapter 31).22

HEALTH ISSUES FACING IMMIGRANTS

The health issues facing immigrants are complicated because people are exposed to a many risks (Box 29-1). There is the risk of the diseases and exposures that are prevalent in the country of origin; migration and travel back and forth to the native country itself may pose health risks; and there is the risk of the illnesses prevalent in the adopted country. The communities in which immigrants often live also have health risks of their own: more environmental risks and higher prevalence of some infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, for example. With greater barriers to medical care, the opportunity to mitigate these risks through health care may also be diminished.

Box 29-1. Health Risks of Immigrants

Risks of home country:

Health care or lack of it

Political climate

Trauma

Persecution

Environmental exposure (wood smoke, pollutants, lead)

Infectious disease

Genetic susceptibilities

Different cancer incidence: gastric, hepatocellular, nasopharyngeal

Risks of travel:

Initial immigration

Travel back and forth

Legal, medical, psychosocial risks

Returning home for medical and dental care

Risks of new country:

New exposures

Lifestyles

Cultural and linguistic differences

Minority status

Legal and health systems

Living in community of immigrants

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree