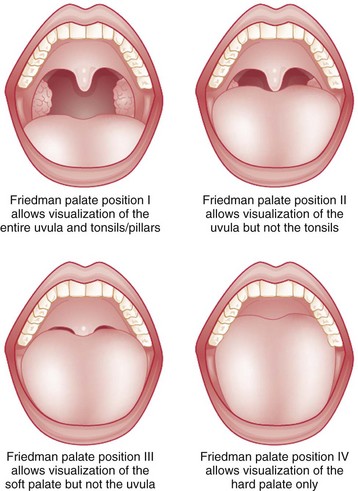

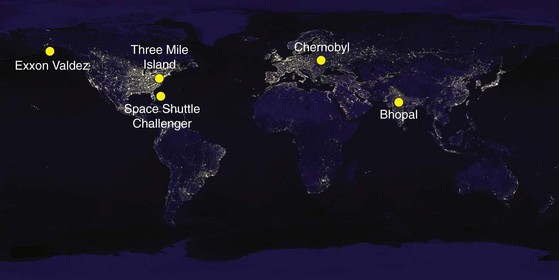

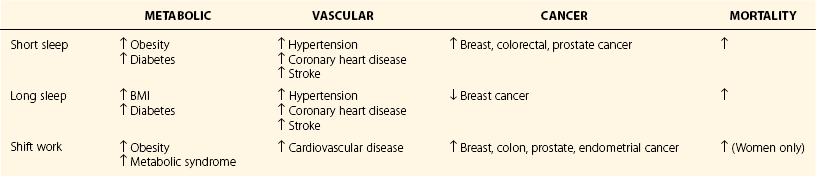

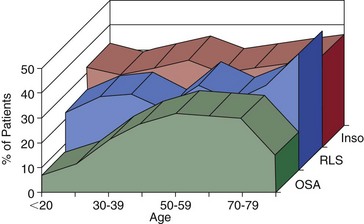

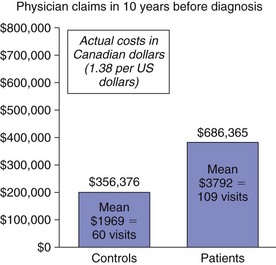

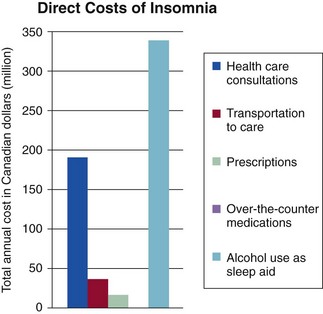

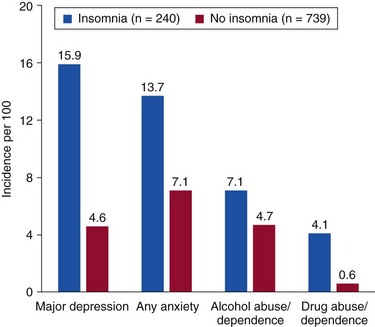

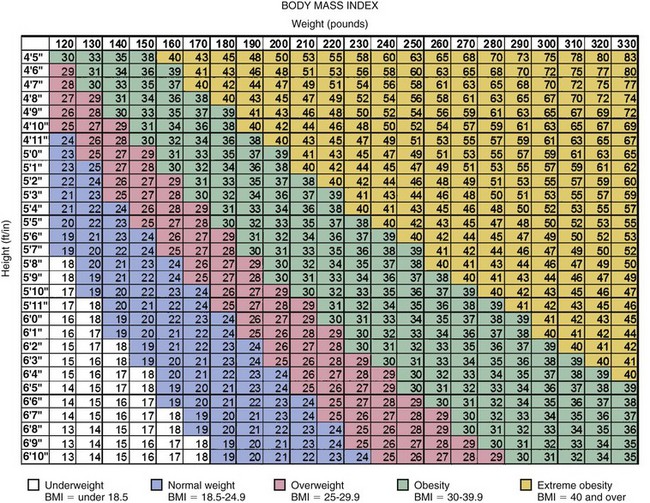

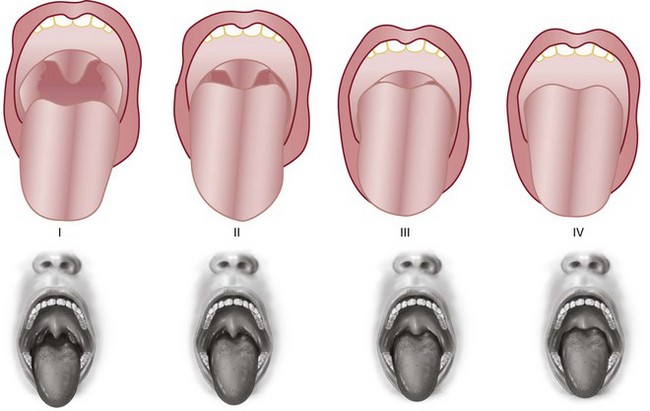

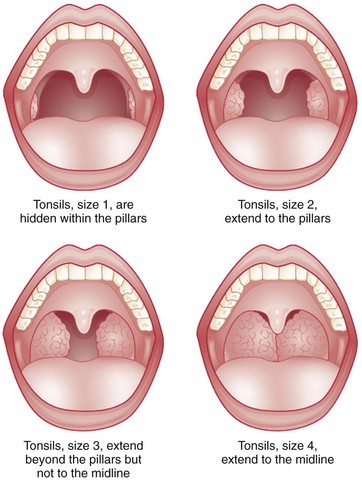

Chapter 8 Disordered sleep is common, and its effect on health and well-being has become increasingly recognized over the past several decades. Unfortunately, the public, patients, and health care professionals often fail to recognize and diagnose these common, treatable disorders. Many catastrophic disasters with devastating effects have been attributed to disordered sleep or sleepiness (Fig. 8-1). Figure 8-1 Disasters in which sleepiness has been implicated. In our busy, 24-hour society, chronic sleep deprivation is ubiquitous. Across the life span, external factors encroach on sleep time. For example, adolescents have a circadian tendency for later sleep and wake times. However, early school schedules truncate the sleep period and cause sleep deprivation, with significant consequences (Box 8-1). For adults in the workforce, increased commute times, long workdays, and nontraditional shifts in combination with social and family obligations restrict available time for sleep. Almost one half of surveyed workers report sleep times less than 7 hours per night on workdays. When individuals curtail sleep, they experience daytime sleepiness that affects their productivity, quality of life, and safety (Box 8-2). National surveys have shown that one third of drivers in the United States have fallen asleep at the wheel (Box 8-3). Furthermore, sleep duration and timing may have an impact on health outside of accidents (Table 8-1). Table 8-1 Health Risks Associated with Short and Long Sleep and Shift Work* *Sleep duration of 7-8 hours in most studies. From Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA: Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J 2011;32[12]:1484–1492; Calhoun DA, Harding SM: Sleep and hypertension. Chest 2010;138[2]:434–443; Knutson KL: Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;24[5]:731–743; Costa G, Haus E, Stevens R: Shift work and cancer—considerations on rationale, mechanisms, and epidemiology. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36[2]:163–179; Tucker P, Marquie J, Folkard S, Ansiau D, Esquirol Y: Shiftwork and metabolic dysfunction. Chronobiol Int 2010;29(5):549–555; and Luyster FS, Strollo PJ, Zee PC, Walsh JK: Sleep: a health imperative. Sleep 2012;33[6]:727–734. Although numerous population-based surveys have shown that sleep disorders are common, they often remain undiagnosed (Fig. 8-2). Failure to recognize, evaluate, and treat someone with a sleep disorder increases health care costs, and sleep disorders are likely to cause or worsen other medical disorders. For example, untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) promotes hypertension. Sleep disorder symptoms are sometimes incorrectly diagnosed as another disorder, such as a mood disorder, with a consequent delay in appropriate therapeutic intervention. As illustrated in Figure 8-3, a Canadian study showed that, compared with matched controls, 181 patients with untreated OSA sought heath care more frequently and spent nearly twice as many nights in the hospital during the 10 years before diagnosis with OSA, resulting in higher costs. Care for insomnia and losses that stem from it also accrue substantial costs (Fig. 8-4). In addition, a longitudinal study of adults showed that a history of insomnia was associated with an increased risk for the development of several psychiatric conditions (Fig. 8-5). Figure 8-2 The percentage of patients in a primary practice with symptoms of sleep disorders. Figure 8-3 Use of health care is high in the decade before the diagnosis of sleep apnea. (Ronald J, Delaive K, Roos L, Manfreda J, et al: Health care utilization in the 10 years prior to diagnosis in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients. Sleep 1999;22[2]:225–229.) Figure 8-4 A questionnaire survey of a community sample of 948 adults from Quebec estimates the total annual cost of insomnia at $6.6 billion. Figure 8-5 Incidence rates (per 100) of new-onset psychiatric disorders during a 3.5-year follow-up period for adults with and without a history of insomnia. (Modified from Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P: Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry 1996;39:411–418.) Accurate and detailed clinical histories and physical exams of patients with disordered sleep are the cornerstones to proper evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Patients’ complaints typically fall into one of the following categories: symptoms suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB; snoring, witnessed apnea); difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep (insomnia); excessive sleepiness; or abnormal behaviors, movements, and sensations before sleep onset, while sleeping, or during awakenings from sleep. In fact, the second edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) has categorized sleep diagnoses in line with the presenting symptoms (Box 8-4). SDB is highly prevalent and can worsen many other sleep disorders. Every patient should be asked about its symptoms (Box 8-5). Assessment of body mass index (Fig. 8-6), Mallampti score (Fig. 8-7), tonsillar size (Fig. 8-8) and Friedman classification (Fig. 8-9) should be done for all patients visiting a sleep clinic. Figure 8-6 Body mass index. (Data from NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: Clinical Guidelines: The Evidence Report. NIH Publication No. 98-4083, September 1998, pp 139-140. National Institutes of Health.) Figure 8-7 Mallampati classification. Figure 8-8 Tonsil size grading. (From Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002:127:13–21.) In the evaluation of a patient with insomnia, it is critical to clarify the specific nature of insomnia symptoms (difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, waking too early in the morning, consistently waking feeling unrefreshed); their frequency, severity, and duration; daytime consequences; and any potential triggers for the current episode (Box 8-6). The answers to these simple questions are often clues to the practitioner about the possible causes of insomnia, which are many and varied (Box 8-7). In particular, these inquiries may differentiate specific insomnia diagnoses from disorders of sleep timing (circadian rhythm sleep disorders [CRSDs], Chapter 9.1) or decreased sleep requirement (short sleeper). For example, an individual with a delayed sleep phase may report difficulties with sleep onset when sleep is attempted at a conventional bedtime but may have no problem with sleep onset at the preferred, later time on the weekends. Conversely, a patient with an advanced sleep phase may chronically experience early morning awakenings but may sleep well from 8 pm to 4 am (Fig. 8-10). In these settings, a diagnosis of CRSD, rather than insomnia, would lead to more effective medical management. Furthermore, the practitioner must investigate whether adequate opportunity for sleep is allowed by the patient’s schedule.

Impact, Presentation, and Diagnostic Considerations

Impact

Sleepiness has been indicated as a contributing factor in the Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown (March 28, 1979), Bhopal pesticide release disaster (December 3, 1984), space shuttle disaster (January 28, 1986), Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion (April 26, 1986), and Exxon Valdez oil spill (March 24, 1989).

Most were undiagnosed. Inso, insomnia; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; RLS, restless legs syndrome. (Modified from Kushida CA, Nichols DA, Simon RD, et al: Symptom-based prevalence of sleep disorders in an adult primary care population. Sleep Breath 2000;4[1]:9–14.)

The above chart depicts direct costs. Indirect costs, absenteeism, and productivity loss (not shown) were estimated at $970.6 million and $5 billion respectively. (Modified from Daley M, Morin C, LeBlanc M, Grégoire J, Savard J: The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep 2009;32[1]:55–64.)

Presentation and Diagnostic Considerations

Clinical Evaluation

History of the Present Illness

Sleep-Disordered Breathing.

Class is determined by looking at the anatomy of the oral cavity as the patient protrudes the tongue. It describes tongue size relative to oropharyngeal size. The test is conducted with the patient in the sitting position, the head held in a neutral position, the mouth wide open and relaxed, and the tongue protruding to maximum. The subsequent classification is assigned based on the pharyngeal structures that are visible. Scoring is as follows: Class 1, full visibility of tonsils, uvula, and soft palate; class 2, visibility of hard and soft palate, upper portion of tonsils and uvula; class 3, soft and hard palate and base of the uvula are visible; class 4, only hard palate visible. (Modified from Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anesth Soc J 1985;32:429–434.)

Insomnia.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree