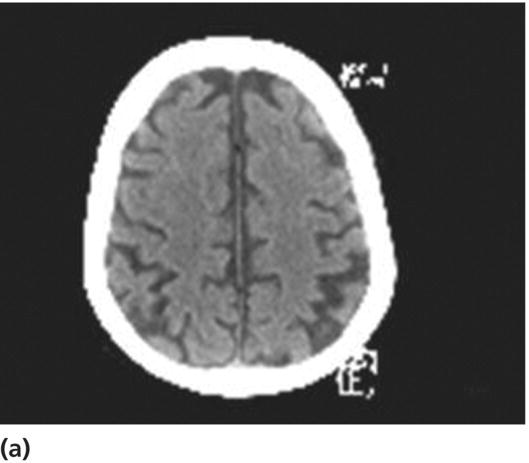

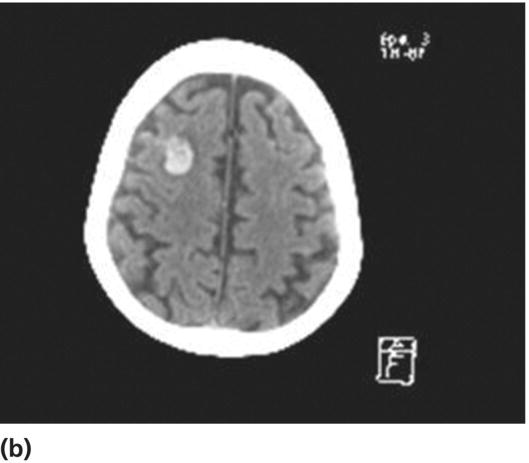

Chapter 5 Pieter E. Vos1 and Dafin F. Muresanu2 1 Department of Neurology, Slingeland Hospital, Doetinchem the Netherlands 2 Department of Neurology, University CFR Hospital, University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Iuliu Hatieganu,”, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Admission to hospital for MTBI depends on clinical and imaging findings. In general, patients with abnormal imaging results will be always admitted to the hospital. When imaging of the head is normal, it is usually safe to conclude that the risk of clinically important brain injury is very low (as long as coagulopathy is ruled out). The majority of all MTBI patients (>90%) show normal CT scan findings [1, 2]. In moderate TBI, lesions are more frequent (20%). Patients with a normal neurological examination and no risk factors (coagulopathy, drug or alcohol intoxication, other injuries, suspected nonaccidental injury, cerebrospinal fluid leak) and a normal CT can be safely discharged home from the ED. Well-done studies indicate that they are at very low risk of secondary deterioration due to delayed intracranial hematoma [3–5]. However, discharge instructions should provide counsel about the risk of persistent postconcussive syndrome, the need for physical and cognitive rest, graded resumption of activities and instructions for follow-up evaluation should postconcussive symptoms persist for longer than 1 week. Even when imaging results are negative, other indications exist to observe patients including prolonged posttraumatic amnesia (PTA), drug or alcohol intoxication, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, and systemic injuries (see Box 5.1). Patients with abnormal CT results that do not require surgery or those with unresolved neurological signs usually require admission to the hospital for observation. Patients in coma (usually GCS ≤ 8) and those requiring immediate craniectomy for life-threatening hematoma will usually be admitted to the ICU of a neurosurgical center (see Chapter 6). Observation of mild and moderate TBI patients should occur until consciousness and anterograde memory are restored. In the UK, National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines have extensively described standardized and protocolized procedures in observing patients with MTBI [3]. Implementation of these guidelines has resulted in improved patient care in the UK. Since the introduction of the guidelines, the number of CTs has increased but fewer patients require admission, because patients with normal imaging results, a normal consciousness, and no other signs and symptoms of concern to the clinician are discharged [4]. Adherence to these guidelines reserves in-hospital observation after TBI for patients with a more severe profile. Comparison of mortality following hospitalization for isolated head injury demonstrates significant differences among countries, depending on the level of organization of trauma services and whether patients are referred to a neurosurgical center. In the UK, a higher rate of mortality was found in severe TBI patients managed in nonneurosurgical centers compared to patients admitted to neurosurgical centers [5]. In a study of TBI admissions, 50–60 % were MTBI patients and risk-adjusted odds of mortality was higher in England/Wales than in Victoria, Australia [7]. A lower percentage of cases managed at neurosurgical centers in England and Wales has been suggested as an explanatory factor in this respect. These findings confirmed an earlier study that only 67% of British severe TBI patients were admitted to a neurosurgical center and only 53% of those initially arriving at a nonneurosurgical center were later transferred to a neurosurgical center [5]. Based on these findings, the NICE guidelines were changed and now recommend transfer of all severe TBI patients to hospitals with 24 h availability of neurosurgical services. As the frequency of life-threatening hematoma in MTBI is low (<1%) and mortality is very low (<1%), transferral of patients from nonneurosurgical centers to neurosurgical centers is probably neither indicated nor feasible. The growing capacity in many hospitals to consult with neurosurgical experts by means of teleradiology further reduces the need for transfer. Because of concerns in the UK about the experience and skills of staff on general and orthopedic acute wards in TBI care, the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1999 recommended that general and orthopedic surgeons should generally no longer be involved in the care of patients requiring a short period of observation for an isolated head injury (http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/report_head_injuries.html). In addition, the NICE guidelines (which first appeared in 2003 and were revised in 2007) cite evidence from a retrospective historical study involving medical and surgical (including head injury) patients that accident and emergency observation wards are more efficient and more cost-effective than general medical or surgical wards for managing short stay observation [3, 8] after trauma. Because patients’ outcomes were not considered, in our opinion, no firm conclusion can be drawn regarding safety issues in relation to where to admit the patient. The indications for admitting patients who did not require initial neurosurgical intervention after mild-to-moderate TBI to a neurosurgical center have also been investigated in Italy. Observation in a neurosurgical unit was compared with observation in a peripheral hospital where a neurosurgeon could be consulted through teleradiology. In the peripheral hospital, 6% of 715 mild-to-moderate severe TBI patients required neurosurgical intervention during observation. Outcome was not different from 47/117 patients who were observed at a neurosurgical unit and subsequently required neurosurgical intervention. Hence, a model of care with observation in a peripheral hospital with neurosurgical consults by teleradiology, repeat CT scanning, and transfer times of 30–60 min to a neurosurgical center was not detrimental for subjects with initial nonneurosurgical lesions after mild-to-moderate head injury [9]. This study also indicates that direct assessment of the CT by a neurosurgeon via teleradiology reduces unnecessary transferrals [10, 11]. Irrespective of the type of hospital, alternatives exist for acute observation of mild and moderate TBI patients. These include accident and emergency ward, surgical ward, orthopedic ward, neurological ward, and neurosurgical ward. The choice of hospital service depends highly on country-specific resources, and the specific UK Royal College recommendations discussed here are probably difficult to generalize to other countries. Development of local protocols based on the organization of trauma systems and resources in each is essential (see also Chapter 3 on prehospital care). The NICE recommendation defines in general terms the criteria for observation “in circumstances where a patient with a head injury requires hospital admission, the patient only be admitted under the care of a consultant who has been trained in the management of this condition during his/her higher specialist training. It is recommended that in-hospital observation of patients with a head injury, including all accident and emergency observation, should only be conducted by professionals competent in the assessment of head injury” [3]. Dutch guidelines, which were in part derived from NICE guidelines, advise to admit the patient at the ward where specialists are available with knowledge on the most vital threats to the patient. Interdisciplinary collaboration is of importance in this respect and sufficient education and skills for the minimal observations is required. In conclusion, it is not possible to generalize recommendations as to where to admit the MTBI patient. Rather, the use of local (defining also interdisciplinary collaboration within hospitals) and regional protocols for observation procedures of MTBI patients is necessary. The main purpose of observation is to detect secondary complications at an early stage. The probability of serious secondary complications, such as result from delayed hematoma, meningitis in patients with skull base fractures, and arterial dissection, is very low but finite. Given the large annual incidence of MTBI, secondary complications are regularly encountered. During hospitalization, general measures can be undertaken to treat or prevent behavioral disturbances after TBI. Promoting the presence of family members, minimizing exposure to external stimuli (such as sounds and light) in the environment, clear communication, and a structured day program may all have a beneficial influence on the patient’s behavior [12, 13]. Also pain and urinary retention can promote agitation after TBI, and adequate treatment of pain with analgesics is as effective as sedative treatment with hypnotics [14]. Specific medical and nursing expertise also has positive effects in the acute phase on the agitated/aggressive patient, reduces the incidence of delirium, and shortens the duration of hospitalization [15]. Based on a few studies of adequate methodological quality, Dutch guidelines recommend that haloperidol is probably effective in treating delirium caused by a general medical condition [15–18]. However, there are considerations based on animal studies that indicate that antipsychotics impair the recovery process and exacerbate TBI-induced behavioral deficits [19, 20]. When treatment is deemed necessary, see in the following for a treatment scheme that can be followed when a prompt result is required. Specific observation measures consist of scheduled assessments of the patient aiming to detect complications at an earliest stage. See Table 5.1 for overview. Table 5.1 In-hospital observation schedule and indications for repeat CT in mild and moderate TBI patients. Modified from Refs. [3, 6]. * In general these observations will occur at the ED. Observations must be carried out by qualified personnel. NICE guidelines advice a second member of staff competent to perform observation to confirm deterioration before involving the supervising doctor. Every deterioration in neurological parameters should be discussed with the medical specialist and causes for deterioration explored. The use of anticoagulation in MTBI has been associated with increased mortality, in particular when the history of head injury is missed (see Figure 5.1). The international normalized ratio (INR) is positively correlated to mortality particularly in the setting of an intracranial hematoma [21]. Retrospective evidence in patients on anticoagulation with head trauma and a normal CT suggest that there is no increased risk for (delayed) intracranial hematoma [22]. A practical approach is then to question every patient with head injury about the use of anticoagulation therapy. All patients on anticoagulation therapy should have their INR checked and the indication for anticoagulation reviewed. These patients should be admitted for neurological observation. If CT demonstrates an intracranial hematoma, the INR should be corrected immediately [23]. Over-anticoagulation can be best corrected with fresh frozen plasma and vitamin K. If spontaneous coagulation disorders or additional injuries with bleeding exist, the decision to transfuse is complex, and consultation with a coagulation specialist should be considered. Transfusions are associated with well-recognized risks, and a recent retrospective study [24] indicates that in patients with moderate coagulopathy (INR 1.4–2.0) not resulting from anticoagulant therapy, transfusion with fresh frozen plasma was associated with worse neurologic outcome. In patients without any abnormalities on the CT and an INR in the therapeutic range, wait and see management under close clinical observation can be carried out. In case of a normal CT and an INR outside the therapeutic range, discontinuation of anticoagulants and vitamin K for several days until normalization of the INR seems rational [6]. The new oral anticoagulant medications including direct thrombin antagonists and factor Xa inhibitors work via different mechanisms and lack reliable laboratory tests to measure levels of anticoagulation. As long as no pharmacological antidote exists and there is no evidence how to best counteract intracranial hemorrhage, the care for patients taking these newer anticoagulants who experience intracranial hemorrhage remains difficult [25]. Figure 5.1 Delayed intracerebral hematoma in an 80-year-old MTBI patient on oral anticoagulation. CT on day 1 is normal (a); CT on day 2 shows intracerebral hematoma (b). After TBI certain stages are recognized [26]. The first stage consists of loss of consciousness or coma, although this is not an obligatory phenomenon for MTBI. By definition, loss of consciousness, if present, lasts shorter than 30 min [27]. The second phase is characterized by a period of disorientation, memory disorders, and behavioral disturbances, also referred to as PTA. By (arbitrary) definition, PTA is under 24 h in MTBI, but can persist for days or weeks in moderate and severe TBI. The third phase is characterized by recovery of motor, cognitive, and behavioral disturbances. Particularly after moderate and severe TBI, where recovery can be incomplete, a fourth stage can be recognized that consists of acceptation of and compensation for the permanent sequelae.

In-hospital observation for mild traumatic brain injury

Which patients should be admitted to the hospital?

Patients with normal intracranial CT findings

Patients with abnormal intracranial CT findings

Role of specialized neurosurgical centers

Observation of patients with mild and moderate TBI: Where to admit at which ward?

Observation in the hospital: Goals and procedures

General measures

Observation

Modality

Frequency

Consider repeat CT

General

GCS = 15

1. Drop of one point in GCS level

2. Severe headache/vomiting

3. Agitation or abnormal behavior

Respiratory rate

0–2 h: every 30 min*

Heart rate/blood pressure

2–6 h: every h

Temperature

>6 h: every 2 h

Blood oxygen saturation

Neurological

GCS < 15

4. Any drop ≥ 2 points in GCS level

GCS

0–2 h: every 30 min*, hereafter every hour until GCS = 15

Pupil size, reactivity

5.Symptoms or signs pupil inequality or asymmetry of limb or facial movement

Limb movements

Tendon reflexes

Anterograde memory

6. GCS = 15 not reached after 24 h

Complications

Anticoagulation

Behavioral complications in the acute phase

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree