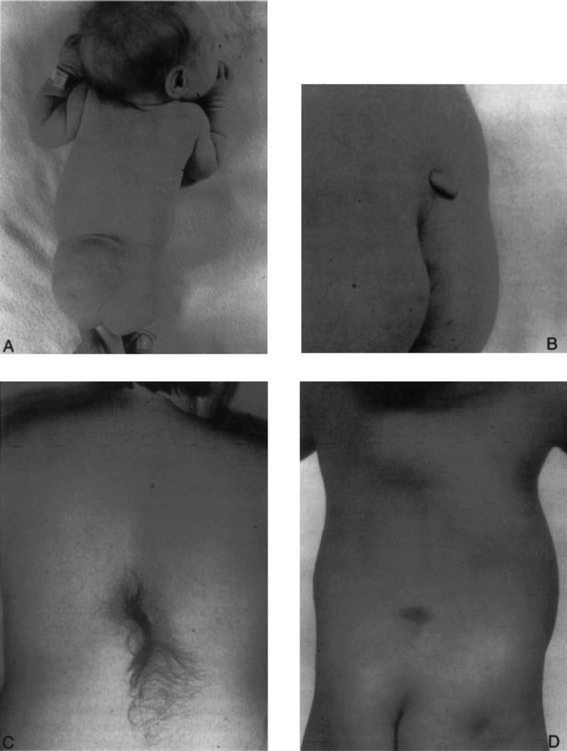

10 Indication and Treatment of Tethered Spinal Cord James M. Drake and Harold J. Hoffman Tethered spinal cord syndrome consists of a group of dysraphic conditions in which the conus medullaris is located in an abnormally low position and is fixed there in a relatively immobile state. Many of these conditions are seen in association with spina bifida occulta, whereas others are seen secondary to repair of a myelomeningocele or lipomyelomeningocele. During fetal life, the spinal cord grows much more slowly than the vertebral column. This leads to a progressive disparity between the termination of the spinal cord and that of the spine; in effect, there is a progressive ascent of the conus medullaris. The most distal part of the spinal cord forms through the process of secondary neurulation or canalization from day 28 to day 48 of the gestational period. Through this process, the caudal cell mass becomes canalized and forms the terminal neural tube, which eventually becomes the conus medullaris. Through the process of regression, the most caudal portion of the neural tube atrophies and forms a fibrous band (called the filum terminale). The band is initially identifiable at day 52. The conus medullaris then ascends within the spinal canal largely through the disproportionate growth of the vertebral column relative to that of the neural tube. At 20 weeks’ gestation, the termination of the conus medullaris is at the level of the space between the L4 and L5 vertebrae. By 40 weeks’ gestation or at term, the conus is at the L3 level and, by age 2 months, has reached the adult L1–2 level.1 Studies by Yamada et al2 show that if stretch is placed on the conus medullaris, progressive ischemia can occur, leading inevitably to neurological sequelae. Anatomical studies by Breig3 have shown that as the normal spine flexes, the spinal cord moves toward the C4 level. This upward movement during flexion is not possible in a conus medullaris that remains tethered. A sudden flexion movement of the spine in the patient with a tethered cord can produce further traction on the conus and lead to symptomatic onset of tethered cord syndrome, even after cessation of growth in adult life. Johnson4 first described the entity of lipomyelomeningocele in 1857. However, it was not until 1950 that Bassett5 emphasized the progressive deterioration in function in patients with a lipomyelomeningocele and stressed the value of early prophylactic surgery. Despite this, management of these lesions remained controversial until relatively recent years. Matson6 believed that surgical management should consist of a cosmetic repair. With the development of prophylactic surgery in cases of occult spinal dysraphism, lipomyelomeningoceles were excluded from consideration because of their complex anatomy and the difficulty of assessing the value of surgery. However, in recent years, the value of carrying out such early surgery has been stressed.7 In 1953 Garceau8 described the filum terminale syndrome in three patients who had a thick filum terminale discovered at laminectomy and who improved following section of the filum terminale. Jones and Love9 reported a further six patients in 1956. In 1976 the author and colleagues reviewed their experience with patients who had a thick filum or spinal cord tethering.10 Cutaneous manifestations in patients with a tethered spinal cord are common. Patients with a lipomyelomeningocele will almost always have a fatty mass visible in the lumbosacral region, which can vary from a large expansive mass to a small lipoma to a caudal tail-like appendage (Fig. 10.1A,B). In addition, other cutaneous manifestations such as hemangioma or dimple may be present. Patients with a diastematomyelia typically have a large hairy patch in the region of the dysraphic spine (Fig. 10.1C). About one third of patients with simple tethering show some form of cutaneous lesion (such as a hairy patch, hemangioma, dimple, or area of thin atrophic skin) or a subcutaneous lipoma (Fig.10.1D). In patients who develop secondary tethering following repair of a myelomeningocele or lipomyelomeningocele, an obvious incision is visible on their backs. Patients with a tethered spinal cord present with a progressive motor or sensory deficit in the lower limbs. Many are seen in the orthopedic surgeon’s office because of a gait disturbance. They can display foot deformities such as pes cavus or an equines deformity (Fig. 10.2). The plastic surgeon may see these patients because of trophic ulceration of the foot due to sensory loss. Scoliosis alone or in combination with other problems is common in patients with a tethered spinal cord. If a spine-straightening procedure is performed with the cord still tethered, sudden and precipitous deterioration in neurological function can occur. Untethering the spinal cord in a patient with a mild scoliosis can frequently prevent progression of or even improve the scoliosis and thus avoid the need for instrumentation. A neurogenic bladder is a common event in patients with a tethered spinal cord, and in many of these patients, signs of a neurogenic bladder are their major manifestation. Back pain and root pain may occur in patients with a tethered cord. The pain is typically intractable and aggravated by movement. It is rarely seen in patients with diastematomyelia or lipomyelomeningocele; however, it may be seen in patients with secondary tethering after repair of a lipomyelomeningocele or myelomeningocele. The pain may radiate along dermatomes and may mimic pain due to other causes. Patients with a tethered spinal cord tend to deteriorate in their function with growth spurts during childhood but also in adult life as a result of trauma and flexion movements of the spine. Sudden and irreversible deterioration in neurological function is possible. Although treatment at first diagnosis has been recommended, recent reports question the effectiveness of prophylactic surgery in lipomyelomeningocele in preventing subsequent deterioration.11,12 All patients with a tethered spinal cord should undergo careful evaluation and documentation of motor and sensory function. Plain x-rays of the spine may show evidence of spina bifida occulta in patients with a tethered spinal cord. The bifid spine is usually below L3 and frequently involves several segments. Ultrasonography helps delineate the level of the conus in the infant. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the investigative tool of choice. It shows the low-lying cord and the conus fixed posteriorly (if it is tethered at the site of a myelomeningocele repair) (Fig. 10.3). Several series of patients have been reported who had clinical features of a tethered spinal cord with normal imaging, or a normal level conus medullaris, and a portion of which improved following division of the filum terminale.13–16

Embryology

Pathophysiology

Historical Background

Clinical Presentation

Patient Evaluation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree