20 Induced Normothermia and Hypothermia Katja E. Wartenberg and Stephan A. Mayer Fever is very common among critically ill neurologic patients, occurring in 23 to 47% in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Ischemic stroke is complicated by fever in 43% of patients during the first week, and 33 to 42% of patients with intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), 40 to 68% with traumatic brain injury (TBI), and 41 to 70% with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) develop fever. Fever is associated with worse neurologic outcome in these patient populations. Therefore, maintaining normothermia (37°C) has become an essential part of ICU management of cerebrovascular disease and brain trauma. Temperature is tightly regulated within one-tenth of a degree by the anterior nucleus of the hypothalamus, particularly the preoptic nuclei. Prostaglandin E2 is the common mediator affecting the temperature set point. Induced mild hypothermia (32 to 34°C) has neuroprotective effects and has been used in patients with elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and anoxic brain injury postcardiac arrest, as well as in other select patient groups. The neuroprotective effects are listed in Table 20.1.

| Early: 0–30 minutes | Lowers metabolic demand Slows O2 consumption, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) stores preserved Every 1°C reduction in body temperature reduces cerebral metabolic rate of O2(CMRO2) by 6–7% |

| Intermediate: Hours | Inhibition of glutamate release, less excitotoxicity Suppression of oxygen-free radicals |

| Late: up to 24 hours | Decreased blood-brain barrier breakdown Less edema and hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke |

History and Examination

History

- Inquire regarding sources of infection, including diarrhea, sputum production, sinus/nasal discharge, discharge from wound sites, indwelling catheter infections and/or decubitus ulcers.

- Inquire regarding recent transfusions or rashes.

- Look at the timing of the fever and the duration of fever.

Physical Examination

- Vitals signs, including core temperature (bladder, pulmonary artery, or other central catheter; airway; rectal; tympanic)

- Examination of the skin and mucous membranes for rashes, secretions, and fluid status

- Look for an infectious focus: Erythema, discharge around lines and tubes, appearance of urine or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), auscultation of the lungs, auscultation and palpation of the abdomen.

- Examine upper and lower extremities for signs of swelling or DVT.

Neurologic Examination

- Assess for signs of meningismus or Kernig’s and Brudzinski signs (see Chapter 10).

Differential Diagnosis

- Infection should always be assumed and thoroughly assessed. The overall frequency of nosocomial infection in neuro-intensive care units ranges from 14 to 36 per 100 patients. The most commonly documented infections are pneumonia (3 to 12 per 100 patients), urinary tract infection (UTI; 3 to 9 per 100 patients), bloodstream infection (1 to 2 per 100 patients), and meningitis or ventriculitis (1 to 9 per 100 patients).1,2,3,4

- Drug-induced fever. Phenytoin, carbamazepine, Β–lactamase-antibiotics, sulfa drugs, etc.

- Transfusion reaction

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Central fever. Clues include very high fever >40 to 42°C, earlyonset fever and fever refractory to antibiotics. Central fever remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and 15 to 28% of fever episodes remain unexplained after an extensive fever work-up. Risk factors include intraventricular hemorrhage, SAH, placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD), and length of stay.5

- Malignant hyperthermia. Syndrome presenting with muscular rigidity, hypermetabolic state with increased oxygen consumption, increased carbon dioxide production (hypercarbia), metabolic acidosis, tachycardia, hyperthermia (with temperatures increasing at a rate of up to 2°C per hour) and rhabdomyolysis (increase in myoglobin and creatinine kinase/creatinine phosphokinase [CK/CPK]). It can be triggered by exposure to halogenated volatile anesthetics and succinylcholine. Treatment includes IV dantrolene and correction of metabolic derangements. An episode of malignant hyperthermia can be delayed up to 24 hours after exposure to offensive medications. It is related to a defect in ryanodine receptors of the sarcoplasmic reticulum which affects intracellular calcium levels. Malignant hyperthermia is genetically and phenotypically related to central core disease (central core myopathy).

- Serotonin syndrome. Spontaneous drug reaction as a consequence of excess serotonergic activity at central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral serotonin receptors. Potential triggers include: monoamine oxidase [MAO] B inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], tricyclic antidepressants, mirtazapine, venlafaxine, yohimbine, St. John’s wort, clonazepam, methylphenidate, lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and cocaine, etc. Presents with a clinical triad of:

- Cognitive effects: Confusion, hypomania, hallucinations, agitation, headache, coma

- Autonomic effects: Shivering, sweating, fever, hypertension, tachycardia, nausea, diarrhea

- Somatic effects: Myoclonus, clonus, hyperreflexia, tremor

Treatment includes discontinuation of the offending medication and administration of serotonin antagonists (cyproheptadine or methysergide) and benzodiazepines.

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Presents with muscular rigidity, high fever, alteration of mental status, autonomic instability, confusion, coma, delirium, tremor along with elevated CPK, leukocytosis, elevated liver function tests, and metabolic acidosis. It is due to alteration of central dopamine neurotransmission and can be caused by dopamine agonists such as Haldol (Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Raritan, NJ) (all neuroleptics, though Clozaril [Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ] has the least potential), and antiemetics such as promethazine, metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and droperidol. Therapy consists of discontinuation of the offensive agent, supportive care, and dantrolene, bromocriptine, and/or benzodiazepines.

- Heat stroke. Body heat production or absorption is greater than the capacity for dissipation, usually due to excessive exposure to heat. Bringing the body temperature down and hydration are of utmost importance.

- Delirium tremens. An acute episode of delirium caused by withdrawal or abstinence from alcohol, typically occurs within 48 to 72 hours from cessation of drinking or benzodiazepine use. Typical presentation includes fever, tremor, confusion, disorientation, agitation, hallucinations, tachycardia, hypertension, and tachypnea. Treatment options include benzodiazepines (lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, etc.).

- Serotonin syndrome. Spontaneous drug reaction as a consequence of excess serotonergic activity at central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral serotonin receptors. Potential triggers include: monoamine oxidase [MAO] B inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], tricyclic antidepressants, mirtazapine, venlafaxine, yohimbine, St. John’s wort, clonazepam, methylphenidate, lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and cocaine, etc. Presents with a clinical triad of:

Diagnostic Evaluation

- Laboratories: As above

- Consider evaluation of CSF (always measure opening and closing pressure).

- Consider evaluation for DVT with upper and lower extremity Doppler ultrasound, or pulmonary embolus with computed tomography (CT) angiography.

- Consider CXR or chest CT for interstitial pneumonia or bronchoscopy for bronchoalveolar lavage.

- Consider checking Clostridium difficile toxin for patients with diarrhea.

- Consider sinus CT to rule out sinusitis.

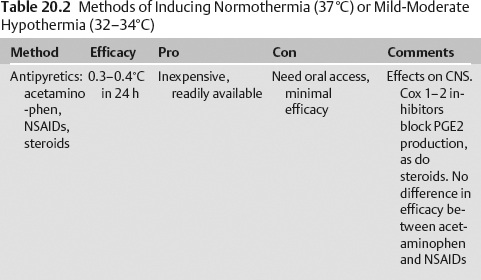

Treatment of Fever, Induced Normothermia (37°C) and Mild-Moderate Therapeutic Hypothermia (32–34°C) (Table 20.2)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree