and Aditya G. Shivane1

(1)

Cellular and Anatomical Pathology Level 4, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK

Abstract

The nervous tissue is well protected by the bone, meningeal coverings and an immune system, from invasion by microbes. A breach in the protective barriers or a deficiency of the immune system may result in infection by various microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa. This chapter begins with the list of terms used to describe infections in different neuroanatomical locations. The microorganisms causing CNS infection may be confined to certain geographic locations, affect specific neuroanatomical compartments and specific age groups. This chapter discusses some of the more common infections affecting the CNS worldwide with an emphasis on the role of brain biopsy and other newer microbiological tests in diagnosing these infectious diseases.

Keywords

InfectionMicroorganismsMeningitisEncephalitisAbscessThe nervous system is protected by the skull and vertebral column, meninges, and blood–brain barrier, from a wide variety of infectious agents. When one or more of these protective barriers are breached, the infectious agents gain access to the CNS tissue and cause infections which have high mortality and morbidity. Infections are caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. The blood-borne route is the most common, but direct invasion and spread along the peripheral nerves can also occur.

Infections can affect different compartments within the nervous system. Some of the commonly used terms to describe the site and nature of an infectious process are listed below, along with their definitions.

Meningitis: Inflammation/infection confined to the leptomeninges with exudate in the subarachnoid space. Spread of infection into the parenchyma may follow. Long-term complications include obstruction of CSF flow resulting in hydrocephalus, and cranial nerve palsies from the thick basal exudate. Viral (lymphocytic) meningitis is more common than bacterial (purulent) meningitis.

Empyema: Collection of pus within the epidural or subdural space. Infection commonly results from local spread or direct contamination (sinusitis, otitis media, trauma or neurosurgery).

Abscess: Accumulation of pus and necrotic tissue within the parenchyma which is generally walled off by fibrovascular capsule and gliosis.

Cerebritis: A purulent non-encapsulated parenchymal infection, which is a stage before abscess formation, where the cerebral parenchyma is infiltrated by acute inflammatory cells.

Encephalitis: Inflammation/infection of the brain usually secondary to a viral infection. There will be necrosis, perivascular lymphocyte cuffing, microglial nodules, viral inclusions and gliosis.

Myelitis: Inflammation/infection of spinal cord parenchyma.

Radiculitis/neuritis: Inflammation/infection of nerve roots.

5.1 Bacterial Infections

5.1.1 Acute Bacterial Meningitis

This is the most common pyogenic infection of the CNS and carries high morbidity and mortality. The causative bacteria are different in different age groups (Table 5.1). The incidence of Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis has reduced drastically in nations which have introduced the conjugate vaccine. Infection most commonly occurs through the haematogenous route, but can also complicate trauma, neurosurgical operations and spread through contiguous foci of infection. Bacteria incite an inflammatory reaction by recruiting polymorphonuclear leucocytes/neutrophils to the site of infection, which then release an array of cytokines and chemokines which result in tissue injury.

Table 5.1

Aetiology of bacterial meningitis

Age | Common organisms |

|---|---|

Neonate (<1 month) | Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp., Citrobacter sp., Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus. |

Children (1 month- 16 years) | Haemophilus influenzae type b, Neisseria meningitidis (Meningococcus), Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B β–haemolytic Streptococci), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus). |

Adults & elderly | Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus), Neisseria meningitidis (Meningococcus), Gram–negative bacilli (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp., Pseudomonas sp.), Listeria monocytogenes. |

The typical CSF findings in bacterial meningitis include marked pleiocytosis, containing predominantly neutrophils, raised protein and reduced glucose. Gram staining may be useful in identifying bacteria. Macroscopic examination of the brain may reveal a purulent exudate in the subarachnoid space over the cerebral convexity (Fig. 5.1a). The exudate may be scanty in patients dying acutely or in those treated with antibiotics. The brain is usually swollen and oedematous. The ventricles may be compressed due to oedema or dilated due to obstruction. Histology shows large numbers of neutrophils within the subarachnoid space (Fig. 5.1b, c) and also along perivascular Virchow-Robin spaces. Intra- or extracellular bacteria may be identified with a Gram stain (Fig. 5.1d). With time, the neutrophils are replaced by chronic inflammatory cells and the exudate transforms into fibrous tissue. The inflammatory cells also invade blood vessels resulting in thrombosis and focal infarcts. Invasion of the ventricular wall results in purulent ventriculitis. The complications of acute bacterial meningitis include- cerebral infarction, obstructive or communicating hydrocephalus, subdural hygroma and subdural empyema.

Fig. 5.1

(a) Brain showing yellowish exudate in the leptomeninges, (b, c) showing dense infiltrate of neutrophils in the subarachnoid space and relatively unaffected cerebral cortex. H&E stain, (d) Gram stain showing positive cocci in pairs and small clusters (arrows)

5.1.2 Abscess

Epidural abscess is a collection of purulent exudate outside the dura mater. This is more common in the spine than the intracranial compartment. The infection is usually secondary to vertebral osteomyelitis, trauma, surgery or sinusitis. It extends along several vertebral levels. The intracranial epidural abscess appears bi-convex in shape and is bordered by skull and dura mater. Histology reveals neutrophils within the purulent exudate and granulation tissue.

Subdural abscess or empyema is a collection of purulent exudate underneath the dura mater and outside the leptomeninges. The infection does not cross the midline. The infection commonly results from local spread (sinusitis, otitis media, and osteomyelitis), trauma, and neurosurgery. Spread from adjacent purulent leptomeningitis may result in subdural empyema in infants. They can be difficult to diagnose on CT scan and therefore, contrast enhanced MRI scan is preferred.

Intraparenchymal/Brain abscess is the most frequent space-occupying infection and commonly occurs due to spread from a local septic focus (like sinusitis, otitis media, and tooth infection) or blood-borne (bacterial endocarditis, bronchiectasis). The various bacteria isolated from a brain abscess include- Streptococcus milleri, staphylococci, Bacteroides sp., Actinomyces sp., and gram-negative bacilli. Risk factors include trauma, neurosurgery and immunodeficiency states. Abscesses resulting from local septic focus are commonly localised to frontal/temporal lobes or cerebellum whereas those resulting from haematogenous spread are localised to the junction between grey and white matter and can be multiple. In the earlier stages, the gross examination of the brain may show only focal congestion surrounded by oedema. This will then progress to a well delineated abscess with outer capsule and necrotic centre (Fig. 5.2). Histologically, the evolution of an abscess can be divided into the following stages- focal cerebritis (days 1–3), late cerebritis (days 4–9), early abscess capsule (days 10–13) and well-formed abscess with firm capsule (from day 14). A well-formed abscess has the following four layers- central necrosis, granulation tissue infiltrated by acute and chronic inflammatory cells, fibrous capsule and reactive brain tissue with gliosis. Serious complications of brain abscess include raised intracranial pressure/herniation and purulent ventriculitis.

Fig. 5.2

Coronal slice of anterior frontal lobe showing an abscess filled with pus and surrounded by hyperaemia and oedema

5.1.3 Chronic Bacterial Infections

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis can involve different compartments within the CNS and can present as epidural/subdural or parenchymal abscesses, tuberculous meningitis and tuberculomas.

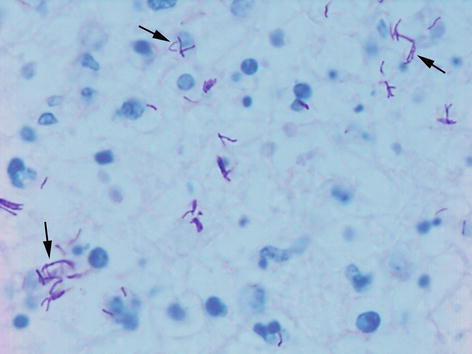

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most common form of CNS TB which occurs either through haematogenous spread from a primary (usually pulmonary) infection or reactivation of latent infection elsewhere in the body. TBM is more common in developing nations, particularly Asia and Africa. In TBM, a thick exudate accumulates over the base of the brain covering the basal cisterns, brainstem and rarely the spinal cord. In advanced infection, the exudate may extend to involve the cerebral convexities also. With time, the basal exudate becomes more fibrous and cause CSF obstruction resulting in hydrocephalus or cranial nerve palsies. The CSF analysis reveals pleiocytosis containing predominantly lymphocytes, raised protein and reduced glucose. Histologically, there is a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells forming granulomas. The granulomas or tubercles may contain central area of necrosis. Ziehl-Neelsen stain may show variable numbers of acid-fast bacilli (Fig. 5.3). The inflammation can also affect the arterial walls (endarteritis obliterans) resulting in ischaemic complications. Confirmation is either by culture (which takes around 6–8 weeks) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing based on amplification of rRNA derived from M. tuberculosis (takes approximately 6–8 h) [1, 2].

Fig. 5.3

Ziehl-Neelsen stain showing numerous acid fast bacilli (arrows) in a case of CNS tuberculosis

Tuberculomas are rounded or multilobular lesions containing a central area of caseous necrosis surrounded by granulomatous reaction composed of lymphocytes, occasional plasma cells, epithelioid macrophages, multinucleated giant cells and variable fibrosis. Tubercle bacilli can be difficult to detect in these lesions. Tuberculomas present clinically as mass lesions and can become cystic, calcified or rupture into the meninges causing meningitis.

TB of the spine (Pott’s disease) which involves the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs commonly results in epidural or subdural abscess. Parenchymal tubercular abscesses have been reported in immunosuppressed and AIDS patients and are histologically similar to pyogenic abscess. The granulomatous reaction is less prominent as a result of reduced cell-mediated immunity and numerous tubercle bacilli are present in the necrotic pus. Infections by non-tuberculous mycobacteria also termed ‘atypical mycobacteria’ (Mycobacterium avium–intracellulare complex, M. fortuitum, M. kansasii) are one of the common causes of opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS.

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum and presents initially as a chancre at the site of inoculation (primary syphilis). The spirochetes then disseminate through blood and manifests as lymphadenopathy, rash, or mucous patches (secondary syphilis). Patients may then progress to latent stage (latent syphilis) which may last for months or years, or develop cardiovascular, ocular, neuroparenchymal and gummatous lesions (tertiary syphilis). Maternal infection can give rise to congenital neurosyphilis in the foetus. The discovery of penicillin saw a dramatic reduction in syphilis cases, but the disease is re-emerging since the advent of HIV infection.

CNS lesions can manifest within a few years after the initial infection as syphilitic meningitis, meningovascular syphilis, or after the latency of decades as parenchymatous (general paresis of the insane and tabes dorsalis) and gummatous neurosyphilis. Syphilitic meningitis is a chronic meningitis composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells. In meningovascular syphilis the inflammation involves arteries (Heubner arteritis) and result in ischaemic lesions in the brain or spinal cord. General paresis of the insane presents with cognitive and motor disturbances and leads to death. The brain appears atrophic and firm with opaque leptomeninges. Microscopic examination shows cortical neuronal loss, gliosis and proliferation of microglia (rod cells). The spirochetes may occasionally be demonstrated using silver stain. Tabes dorsalis is due to degeneration of posterior columns secondary to chronic inflammation within the dorsal nerve roots and dorsal root ganglia. The spirochetes are absent in these lesions. A gumma is a round, firm, rubbery lesion with central necrosis and surrounded by a granulomatous reaction, similar to those seen in tuberculomas.

Borreliosis is a spirochetal infection transmitted by tick and louse bites and includes relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis and other Borrelia sp.) and Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi). Lyme disease is a multisystem disorder common in northern temperate regions and involves the skin, cardiovascular system, joints, and peripheral and central nervous systems. The typical initial skin lesion which appears as maculopapular rash is referred to as ‘erythema chronicum migrans’. The nervous system lesions include chronic meningitis, parenchymal chronic inflammatory infiltrates, cranial nerve palsies (commonly facial nerve), and polyradiculitis. Late complications include axonal neuropathies and encephalopathy.

Leptospirosis is caused by the spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. The infection is transmitted by water contaminated with rat’s urine. CNS lesions include lymphocytic meningitis, subarachnoid and intracerebral haemorrhage and occasionally encephalitis or myelitis.

Brucellosis (Malta fever) is caused by aerobic Gram-negative bacteria Brucella sp., which is transmitted by raw dairy products and by direct contact with animal products such as the placenta. Neurobrucellosis can manifest as diffuse chronic meningitis, encephalomyelitis, radiculitis and neuritis (particularly acoustic nerves) and vasculitis.

Actinomycosis is caused by anaerobic, filamentous, Gram-positive bacteria, Actinomyces israeli and Actinomyces bovis. They are commonly found in the oral cavity or in the large intestine as commensals and enter tissues through breaks in the mucosa. CNS lesions are uncommon and occur through either direct extension or via the bloodstream from a focus elsewhere in the body. In brain, they present as multilocular abscesses with central necrosis, acute or chronic inflammatory cells, granulation tissue and filamentous bacteria forming yellowish-brown sulphur granules. Other lesions include meningitis, meningoencephalitis, subdural empyema and epidural abscess.

Nocardiosis is caused mainly by Nocardia asteroides, a ubiquitous filamentous aerobic organism. They cause brain abscess or meningitis in debilitated or immunosuppressed patients. Haematogenous spread from a primary pulmonary infection is the commonest route. The spinal cord may be occasionally affected. The abscesses contain thick fibrous walls and acute inflammatory exudate. The organism can be identified using Grocott’s silver stain.

Whipple’s disease is a multisystem disorder first described by George H. Whipple in 1907, later discovered to be caused by a Gram-positive actinomycete Tropheryma whippleii. The disease is common in men between fourth and seventh decades and predominantly involves the intestinal tract. The neurological disease develops in a minority of patients and includes dementia, ophthalmoplegia, hypothalmo-pituitary dysfunction and myoclonus. The lesions are present throughout the CNS and microscopically show accumulation of bacteria-laden macrophages around blood vessels, variable lympho-plasmacytic response, and gliosis. The bacteria are PAS-, Gram- and methanamine silver positive and appear as sickle-shaped inclusions within the macrophages or extracellular tissue. The diagnosis can readily be made by small intestinal biopsy or by PCR testing for specific bacterial 16S rRNA [3].

Rickettsia and Mycoplasma infections of the CNS are relatively rare. Rickettsiae have staining characteristics similar to Gram-negative coccobacilli and cause typhus group infections, spotted fever and Q fever. They are transmitted by ticks or mites, fleas, or lice. Rickettsiae organisms cause damage to blood vessels. The brain in fatal cases may show oedema, perivascular lymphocytes and macrophages, microinfarcts, or haemorrhages. Mycoplasma are organisms which lack cell wall. Mycoplasma pneumoniae cause pneumonia in children and young adults. Neurological complications are seen in less than 5 % of cases and include meningitis, encephalomyelitis, cerebral infarction, and polyradiculitis. Diagnosis is usually confirmed by serology and PCR testing.

5.2 Viral Infections

5.2.1 Aseptic Meningitis

Aseptic meningitis can be caused by a wide range of viruses (echovirus, coxsackie virus, herpes simplex virus 2, mumps virus, HIV, lymphochoriomeningitis virus, arboviruses, measles virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus), non-viral infections (e.g. partially-treated bacterial meningitis, syphilis), inflammatory diseases (e.g. Behcet’s disease), tumours (e.g. dermoid and epidermoid cysts) and adverse reaction to drugs (e.g. ibuprofen, antibiotics). The CSF analysis reveals pleiocytosis containing predominantly lymphocytes, mildly raised protein and usually a normal glucose. This is usually a benign self-limited condition characterised by a scanty infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells within the leptomeninges, around superficial cortical vessels and choroid plexus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree