Inositol in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders

Robert H. Belmaker

Joseph Levine

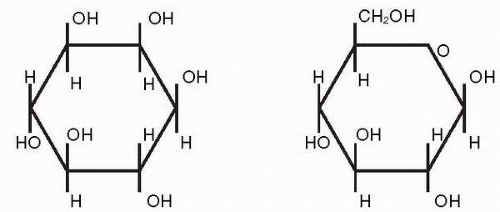

Inositol is a sugar alcohol and a structural isomer (although not stereo-isomer) of glucose (Fig. 7.1). It differs from glucose because all six carbon atoms are found within the ring of the molecule. Located primarily within cell membranes, inositol is ubiquitous in biologic organisms; the average adult human consumes about 1 g of inositol in the daily diet. It is regarded by some as a vitamin (1) and by European folk wisdom as a remedy for neurasthenia and mild depression.

Berridge et al. (2) suggested that lithium acts in bipolar disorder by inhibiting the enzyme inositol-1-monophosphatase and causing a relative inositol deficiency. A possible excess of inositol in mania suggested its possible deficit in depression. Barkai et al. (3) reported low levels of inositol in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed patients. The authors therefore performed a pilot study of 6 g per day of inositol in patients with resistant depression; this was in addition to ongoing medication (4). The trial results were positive, and the only side effect reported was occasional mild flatulence. The authors then proceeded to a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of inositol, 12 g per day, versus a placebo in depression (5).

DEPRESSION STUDY

Patients who were referred to the study and who gave informed consent had all failed antidepressant treatment or had dropped out because of side effects. No medications other than inositol or the placebo were permitted during the trial, except for oxazepam, up to 15 mg daily, or an equivalent benzodiazepine if the patient had been taking it before the study began.

Twenty-seven patients completed the trial. All patients were given inositol or glucose in identical containers according to a prearranged random code. The drug was in powder form, and patients were instructed to take 2 teaspoons dissolved in juice both in the morning and in the evening. A modified treatment emergent symptom scale was used to monitor side effects. Hematologic studies, blood chemistry, liver function, and kidney function were assessed at baseline and after 4 weeks of inositol treatment.

Scores on the Hamilton Depression (HAMD) scale declined from 32.9 ± 5 at baseline to 28.7 ± 7 at 2 weeks and to 28.9 ± 10 at 4 weeks in the placebo group, and from 33.4 ± 6 at baseline to 27.3 ± 8 at 2 weeks and to 21.7 ± 10 at 4 weeks in the inositol group. Analysis of variance of the final improvement scores (baseline minus week 4) for all subjects showed that inositol reduced the HAM-D significantly more than the placebo did (F1,26 = 4.48, P = 0.04). This difference was not yet apparent after 2 weeks of treatment.

PANIC DISORDER STUDY

Because some antidepressant agents are also effective against panic disorder, the authors decided on a trial of inositol treatment for panic disorder (6). Patients previously on medications withdrew from them at least 1 week before commencing a formal washout period; only two patients actually withdrew from medications this close to the study. Patients were prepared to go off conventional treatments in the hope of finding a new treatment without troubling side effects. The only medication allowed beside inositol and the placebo was oral lorazepam, 1 mg, as needed for anxiety.

The placebo was mannitol (number of subjects N = 10) or glucose (N = 11). The treatments were supplied in an identical-appearing white powder form with similar taste and solubility. Patients took 6 g of medication twice a day dissolved in juice. All subjects began with a 1-week run-in period on open placebo (N = 10) or no medication (N = 11). Thereafter, each patient was randomly assigned to double-blind placebo or inositol for 4 weeks; he or she then crossed over to the alternate substance for another 4 weeks. Patients completed daily panic diaries in which they recorded the occurrence of panic attacks, the number of symptoms (from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. [DSM-III-R] list) in each attack, and the subjective severity of each attack. Investigators reviewed the diaries at each weekly assessment and completed the Marks-Matthews Phobia Scale, HAMD, and the Hamilton rating scale for Anxiety (HAMA). A panic score was calculated by taking the mean of severity of attacks (range, 0 to 10) and the number of symptoms per attack and multiplying this average by the number of attacks per week. The results at the end of the run-in week were used as baseline measures.

Twenty-five patients were enrolled; 21 patients completed the study. Nine men and 12 women participated, with a mean age of 35.8 years (SD, 7 years). Five patients had panic disorder, and 16 had panic disorder with agoraphobia. The mean duration of illness was 3.9 years (SD, 3 years). Every outcome measure improved more on inositol than on the placebo. For a number of panic attacks, panic scores, and phobia scores, this difference was significant. The effect of inositol appeared to be clinically meaningful; the number of attacks per week fell from approximately 10 to approximately six on placebo and to approximately three and one-half on inositol. Ten of the 21 subjects were classified as true inositol responders, and three were placebo responders.

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER STUDY

The role of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is supported by the specific effectiveness of serotonin reuptake inhibition in this illness

and the ability of serotonin agonists to exacerbate the syndrome. Rahman and Neuman (7) reported that desensitization of 5-HT receptors is reversed by the addition of exogenous inositol. The authors therefore planned a trial of inositol in OCD. Since anti-OCD doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually higher than antidepressant doses, the authors chose to give 18 g per day of inositol in OCD (8).

and the ability of serotonin agonists to exacerbate the syndrome. Rahman and Neuman (7) reported that desensitization of 5-HT receptors is reversed by the addition of exogenous inositol. The authors therefore planned a trial of inositol in OCD. Since anti-OCD doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually higher than antidepressant doses, the authors chose to give 18 g per day of inositol in OCD (8).

Fifteen patients entered the trial; 13 completed the study and were included in data analysis. The trial was of crossover design, with 6 weeks in each phase. Six patients started the trial on the placebo and seven patients on inositol. Patients were drug free for at least 1 week before beginning the trial. No washout occurred between the phases of the crossover. The dose of inositol (18 g per day) was given as 2 teaspoons in juice three times daily; the placebo was glucose. OCD was assessed using the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). Ratings were performed at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 weeks. The mean age of the subjects was 33.7 years (23 to 56 years), and eight women and five men participated. Mean duration of illness was 8.1 ± 5 years (range, 1 to 17 years). Five patients had responded well in the past to SSRIs; five had had partial responses; three had had poor responses. None met the criteria for major depression. Only lorazepam, up to 2 mg daily, was allowed in addition to the study drug.

Mean improvement from baseline to 6 weeks in the Y-BOCS on inositol was 5.9 ± 5.0 and on placebo 3.5 ± 2.8 (P = 0.04, paired t-test). For the obsessions subscale, the mean improvement on inositol was 3.0 ± 2.8 versus placebo, 2.0 ± 1.6 (P = 0.12, NS). For the compulsions subscale, the mean improvement on inositol was 3.0 ± 2.8 and for the placebo 1.5 ± 1.4 (P = 0.03). Patients who had previously responded to SSRIs also responded to inositol; those who had been resistant in the past were resistant to inositol as well.

BULIMIA AND BINGE-EATING STUDY

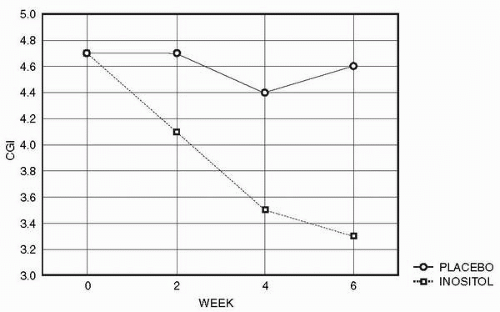

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a highly prevalent, but severe, eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by purging. Binge eating disorder (BED) is a related disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating without the excessive weight and shape concern of BN. Several studies have reported that SSRIs yield therapeutic benefits in BN (9) and BED (10). Because the indications of inositol so far appeared to parallel those of SSRIs, the authors performed a study of inositol in BN and BED (11). The dose of 12 to 18 g per day of inositol was of a caloric value that is equivalent to 2 teaspoons of table sugar and thus was of negligible dietary impact for eating disorder patients. Patients with anorexia nervosa or patients with a body mass index less than 18 were excluded. The trial was of double-blind crossover design. Additional psychoactive medication was not permitted. After 1 week of single-blind run-in placebo, patients were randomized to inositol or placebo for 6 weeks. At the end of 6 weeks, the patients were crossed over to the alternative treatment for an additional 6 weeks. Evaluations were based on those used in the fluoxetine multicenter bulimia study (12). Patients were evaluated at baseline and every 2 weeks thereafter with the Eating Attitude Test (EAT) (13), the Visual Analogue Scale (14) of severity of binge eating (VAS-B), the clinician-administered Clinical Global Impression (CGI) for severity, the Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI) (15), the HAMD, and the HAMA. Twelve patients completed the trial.

Results showed significant effects of inositol treatment on CGI (main effect of treatment: F1,11 = 6.8, P = 0.02, with a post-hoc effect at week 6, P = 0.046) (Fig. 7.2) and VAS (drugtime interaction F2,22 = 4.2, P = 0.03; main effect of treatment: F1,11 = 5.5, P = 0.04), a borderline significant effect on the EDI, and no effect on the EAT. Results in the subgroup of BN patients (N = 9) were similar, with VAS-B main effect of treatment F1,8 = 4.3, P = 0.07 and treatment by week interaction F2,16 = 3.7, P = 0.04. Using the VAS-B and a criterion of

at least 50% improvement from baseline, five patients improved to criterion on inositol and only one did so on the placebo (x2 = 3.6, P < 0.06).

at least 50% improvement from baseline, five patients improved to criterion on inositol and only one did so on the placebo (x2 = 3.6, P < 0.06).

COMBINATION AND AUGMENTATION STUDIES OF INOSITOL WITH OTHER ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS

Antidepressant pharmacotherapy is ineffective in about one-third of depressed patients, and antidepressant medications take several weeks to ameliorate symptoms. Since several classes of antidepressant treatments exist, testing whether combinations of effective treatment might yield higher response rates or more rapid response than monotherapy has seemed logical. However, most studies show no advantage for a combination strategy in depression. This contrasts with the augmentation strategy in resistant depression [i.e., the second agent is added after the failure of the first one (16, 17, 18)]. The failure of a second drug, which is effective by itself, to add benefit to a basic drug can possibly be taken as evidence that the two share a mechanism of action.

Inositol may act therapeutically in depression via the intracellular phosphatidyl inositol second messenger cycle, serving as a second messenger system for 5HT-2 receptors (see the following section). The SSRIs act via inhibition of serotonin reuptake within the synaptic cleft. The authors hypothesized that adding inositol to SSRIs might speed up the response to SSRIs or that it might significantly enhance the degree of patient response or the percentage of patients responding. Twenty-seven depressed patients completed a double-blind, controlled, 4-week trial of an SSRI plus a placebo or plus inositol (19). The HAMD was used as an assessment tool at baseline and at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks. No significant difference was found between the two treatment groups. No serious side effects were exhibited by this combination compared to those with SSRI alone.

Similarly, current SSRI treatments for OCD provide only partial benefit. Given the positive previous study of inositol alone in OCD, ten patients diagnosed with OCD by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) received 18 g of inositol for 6 weeks and a placebo for 6 weeks, in addition to ongoing SSRI treatment in a double-blind, randomized crossover design. Weekly assessments included the YBOCS, the HAMD, and the HAMA. No significant difference was found between the two treatment phases (20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree