- Accurately defining chronic insomnia as a sleep disorder is problematic since it is so common and widely heterogeneous in its nature

- Primary chronic insomnia almost certainly has long-term health consequences and is strongly associated with depression, hypertension and a variety of physical or somatic symptoms

- Chronic insomnia is most commonly precipitated by a trigger or life event in predisposed subjects and is subsequently fuelled over months or years by maladaptive thoughts and habits

- Psychophysiological insomnia accounts for most cases of primary insomnia and is thought primarily to reflect excessive cognitive arousal

- Mild insomnia may respond to simple advice on sleep hygiene together with relaxation therapy

- Structured cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) tailored for insomnia is a the best proven treatment for severe or resistant cases

- Pharmacological treatment for chronic primary insomnia is controversial although it has a role in selected cases, possibly in combination with other strategies

- A number of sedative drugs are used as surrogate hypnotic agents even though overall sleep quality is often not improved due to their adverse or inhibitory effects on deep non-REM sleep

Dissatisfaction with overnight sleep is such a common complaint that it is often overlooked or, at best, incompletely assessed. Indeed, if specifically asked about sleep quality, approximately one-third of those visiting a general practitioner will report problems, a proportion that rises to two-thirds of those attending psychiatry services. Insomnia is reported more in females and generally increases with age.

Transient or short-term insomnia, usually triggered by a recognisable life event or stressor, is a universally recognised phenomenon. However, the underlying mechanisms or causes of chronic insomnia are often more obscure. Furthermore, the pathways for managing significant insomnia presenting to primary care are generally very poorly developed, creating frustration for patients and physicians alike.

Defining chronic insomnia as a formal sleep disorder is challenging, especially as it is a heterogeneous complaint. Broadly, subjects can report difficulty with any aspect of sleep, whether it is initiation, duration, consolidation or quality. The problem persists despite a desire to sleep normally with adequate time and opportunity for satisfactory sleep.

Most authorities would suggest an approximate benchmark of 30 minutes either trying to achieve sleep or a similar time spent awake after sleep onset as reflecting significant insomnia. The problem needs to have been present most nights of the week for over one month and, importantly, to have resulted in a degree of daytime impairment. Typical daytime symptoms include lethargy, malaise and cognitive blunting, especially in tasks involving attention or concentration. In severe cases, the problem completely dominates a subject’s life such that vocational, social or school performance is severely compromised.

Importantly, insomnia is recognised as a reliable independent risk factor for developing depression and hypertension. Furthermore, numerous somatic symptoms, such as increased muscle tension, gastrointestinal upset and headache, are often intimately associated with insomnia.

Although the distinction may often be blurred, it is useful to consider insomnia either as a primary phenomenon, reflecting an intrinsic sleep disorder, or as having an extrinsic cause largely due to factors such as the environment, drugs or other medical conditions. Broadly speaking, an important clue that insomnia is a primary rather than a co-morbid phenomenon is that subjects report a complete inability to nap under any circumstances during the day, despite persistently restricted or poor quality nocturnal sleep. At its simplest, a subject with primary insomnia can be considered ‘tired but wired’.

Mechanisms of insomnia

There are at least four interacting factors that can contribute to insomnia in clinical practice.

Homeostatic factors

It should be emphasised that normal sleepiness is a true drive state that builds exponentially with prolonged wakefulness and which can only be satiated by sleep itself. If the sleep drive is ‘weak’ for some reason or, perhaps more commonly, if someone is overly aroused or ‘wakeful’, insomnia may result. Although the neurochemistry of arousal and sleep onset systems in the brain is increasingly understood, consistent or objective abnormalities in insomniacs are difficult to demonstrate with current technology, even in severe cases. This may partly be due to the heterogeneous nature of the condition.

Inhospitable environment

A large number of adverse environmental factors may interfere with sleep and might not be readily recognised by an insomniac (Box 5.1). Alternatively, it is not uncommon for a person to recognise a possible cause for their insomnia but be unaware that there may be a potential remedy. Successful treatment of a bed partner’s severe snoring is a relatively common example.

| Loud noises | Bed partner (snoring, coughing, sleep-talking) or pets (e.g. barking); music, television, telephone; traffic, trains, mechanical sounds (e.g. a lift) |

| Extreme temperature | Heat (no air conditioning in hot climates); cold (insufficient bedcovers or their removal during night) |

| Bedding materials | Bed or pillow uncomfortable; Allergy to washing powder or feathers in pillow |

| Light | Bright light during summer in high latitudes; Normal sunlight during the day if working night shifts |

| Body positioning | Seated position (e.g. when using public transport); Cramped bed if subject or partner significantly obese |

| Movement | Vibration or turbulence if sleeping on public transport; Body movements (e.g. leg kicks from partner) |

Up to 20% of people are aware there may be excessive noise in the sleeping environment. This may not be enough to fully wake subjects but might produce lighter and less refreshing sleep. Almost certainly, subjects vary in their ability to ‘gate’ extrinsic predictable noises at night, explaining why many find it possible to sleep peacefully next to train lines.

Maladaptive coping mechanisms and behaviours

Many potentially reversible behaviours, habits or beliefs exist to promote or worsen insomnia (Box 5.2).

- Engaging in stimulating activities up to the point of bedtime

- Using the bedroom for activities other than sleep

- Inconsistent sleep–wake rhythm through the week

- Excessive checking of the clock during the night

- Consuming foods before bed that might promote acid reflux and heartburn

- Inappropriate caffeine intake

- Using alcohol habitually as a sleep aid

- Inadequate physical activity or exercise during the day

It is obvious that both the body and mind need to be in a relaxed state before sleep can be initiated. This can often be overlooked with increasing trends for people to engage in work or other arousing activities right up to the intended time of sleep onset. The consequent inability to suddenly fall asleep then creates frustration and fuels further problems.

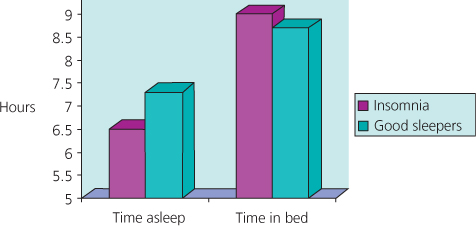

Insomniacs will often lose confidence that they can fall asleep in their bedrooms by a process of negative conditioning. Such patients will report significant sleepiness late evening whilst relaxing in the living room which disappears immediately they enter the bedroom. The failure of the bedroom to cue sleep occurs particularly in those who habitually use the room for activities such as studying or paying bills, for example. Paradoxically, compared to good sleepers, subjects with this type of insomnia generally spend an inordinate large amount of time in the bedroom across 24 hours but a much smaller proportion of it actually asleep (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Graph demonstrating the average time a group of typical insomniacs spends in bed (around nine hours) compared to time asleep (6.5 hours). This contrasts with good sleepers who spend 8.5 hours in bed, 7.5 hours of which are estimated asleep.