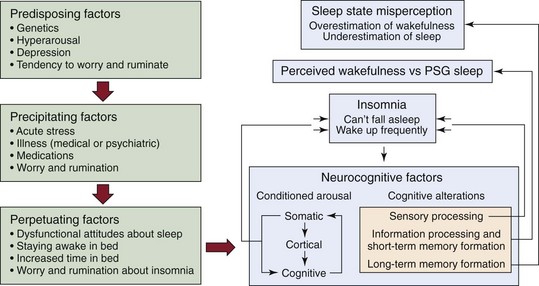

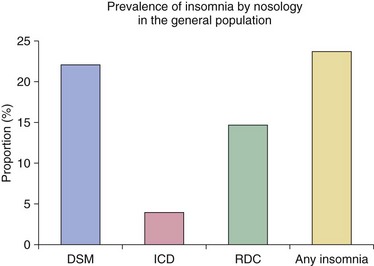

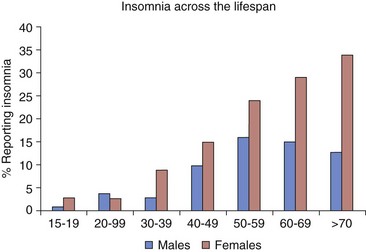

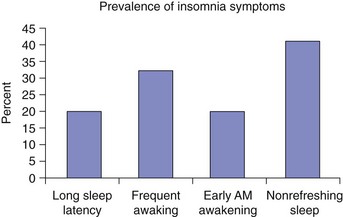

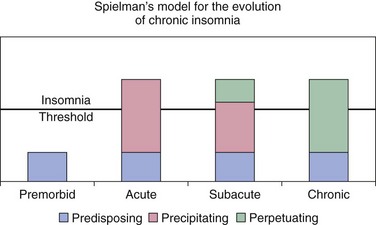

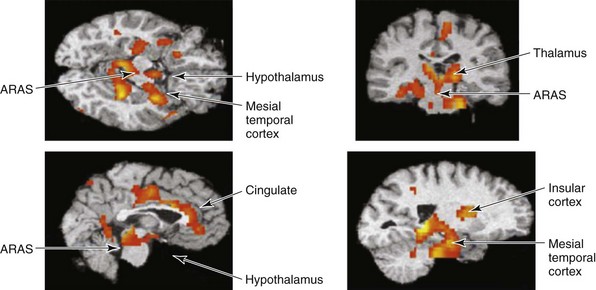

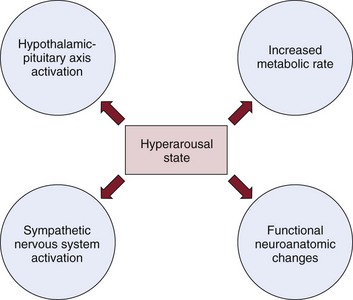

Chapter 10 Approximately 30% to 40% of adults have some degree of disturbed sleep during any given year. Estimates of the prevalence of those who meet formal criteria for an insomnia diagnosis vary from between 4% and 22%, depending upon the specific diagnostic criteria used (Fig. 10-1). Insomnia is more prevalent in women than in men, but the propensity to develop insomnia increases in both genders with advancing age, largely because of the increased occurrence of sleep-disruptive comorbidities that comes with aging (Fig. 10-2). Isolated sleep maintenance complaints are more common than isolated sleep onset complaints, although a sizeable percentage of insomnia sufferers have mixed complaints (Fig. 10-3). Insomnia symptoms may vary over time, but a substantial proportion of those who develop insomnia have persistent sleep difficulties that fail to remit without intervention. Figure 10-1 Prevalence of insomnia by diagnostic nosology. Figure 10-2 Percentages of men and women who report insomnia. Figure 10-3 Of the main insomnia symptoms, the most common is sleep maintenance difficulties. Much about the etiology and pathophysiology of insomnia remains unknown. However, it is recognized that various factors may contribute to the development of insomnia, including comorbid sleep disorders, psychiatric and medical illnesses, certain medications and illicit substances, sleep-disruptive environmental circumstances, and a range of psychologic and behavioral factors. Although no single model explains all forms of insomnia, some theories and models are helpful. Spielman’s 3-P model highlights the roles of predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors and is useful in helping understand the evolution of insomnia. According to this model, insomnia propensity may exist as a latent trait in predisposed or vulnerable individuals but typically does not become manifest until precipitating circumstances, such as a serious illness or stressful life event, push the individual over the insomnia threshold. Once the insomnia is present, it evolves from an acute to a more chronic problem, as the individual develops maladaptive responses to the sleep-wake disturbance that only serve to perpetuate it (Fig. 10-4). This model serves as a useful heuristic for understanding the evolution of chronic insomnia and has served as the basis for more complex theoretic models proposed for explaining the development and nature of insomnia complaints (Fig. 10-5). Figure 10-4 Spielman’s 3-P model for insomnia. One of the underlying assumptions of current theories is that insomnia patients are in a state of hyperarousal over the 24-hour period and that this propensity toward hyperarousal leads patients to develop sleep disturbances when stressed. This hyperarousal can be viewed as a predisposing factor for insomnia and may be the basis for some individuals’ development of insomnia in response to certain medical conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, hyperarousal may also serve a perpetuating role that makes sleep difficult throughout the 24-hour day. Numerous studies have supported the presence of physiologic hyperarousal among insomnia sufferers. For example, imaging studies conducted with positron emission tomography show that various brain areas of insomnia patients show less deactivation during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep than do similar brain areas in normal sleepers (Fig. 10-6). Other research also supports the notion that the hyperarousal state results in measurable changes in physiologic systems other than the central nervous system (Fig. 10-7). Figure 10-6 Hyperarousal in insomnia. Figure 10-7 Studies have documented a hyperarousal state in insomnia patients. The insomnia features described in Box 10-1 are found in three groups of patients (Fig. 10-8): 1) patients in whom a medical or psychiatric condition coexists with the insomnia (comorbid insomnia); 2) patients in whom the primary sleep disorder may include symptoms of insomnia (primary sleep disorders); and 3) patients in whom insomnia exists in the absence of a psychiatric, medical, or other primary sleep disorder (isolated insomnia disorder).

Insomnia

Epidemiology

Prevalence estimates of insomnia diagnoses in the general population vary as a function of the diagnostic criteria and nosology used for ascertainment. DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; ICD, International Classification of Diseases (version 9); RDC, research diagnostic criteria. (Mofidied from Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al: Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, rev 10; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, ed 2 criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biol Psychiatry 2011;69[6]:592–600.)

Insomnia is more common in women than in men in all age groups. (Data from Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Guilleminault C: How a general population perceives its sleep and how this relates to the complaint of insomnia. Sleep 1997;20[9]:715–723.)

Note that the prevalences add up to more than 100%; therefore many patients have more than one insomnia symptom. (Data from Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey: I. Sleep 22[suppl 2]:S347-S353.)

Pathophysiology of Insomnia

Insomnia develops and is a function of predisposing and precipitating factors and is sustained over time by perpetuating factors.

The red and yellow areas show that regions of the brain that are normally wakefulness-promoting areas do not decrease their metabolic rate with sleep. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography was used to evaluate regional glucose metabolism in the brain. This suggests that the brains of patients with insomnia are hyperaroused. ARAS, ascending reticular activating system. (From Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, et al: Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161[11]:2126–2128.)

Increases in cortisol (hypothalamic-pituitary activation), increases in heart rate response (sympathetic nervous system activation), an increased 24-hour metabolic rate, and changes that indicate increased metabolic rate are seen in regions of the brain that promote wakefulness.

Types of Insomnia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine