As shown in Table 6.1, there have been five reports of the efficacy of intensive speech restructuring with school-age children. Thus far, the most promising evidence for the efficacy of intensive speech restructuring with children has come from Craig et al.’s (1996) Phase II non-randomised controlled clinical trial. In this trial, participants were assigned to one of either a standard or parent-focused speech restructuring programme or a no-treatment control group (an EMG biofeedback group was also used but is not discussed here). Both speech restructuring treatment formats provided positive and similar stuttering reductions.

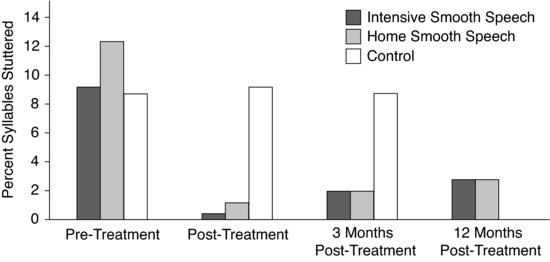

These outcomes are shown in Figure 6.1. A limitation of Figure 6.1 is that it contains data for children 7–14 years old, and may not be representative of the school-age group 7–12 years. However, assuming that it is representative, immediately post-treatment the children showed significant reductions in stuttering, with a mean percent improvement in fluency of 95% across conversation, telephone and home measures. Percent improvement reduced to 72% at 1 year post-treatment, with approximately one-third stuttering in the range of 5–18 percent syllables stuttered (%SS), indicating significant relapse (Hancock and Craig, 1998). Nonetheless, measures of speech naturalness and state and trait anxiety improved post-treatment and those gains were reasonably well maintained at 1 year post-treatment. At 5 years follow-up, percent improvement was 76% and parent reports indicated that approximately one-third of children had shown no relapse (Hancock et al., 1998). However, around 13% of children had relapsed back to pre-treatment levels of stuttering (Craig, 2010).

Figure 6.1 %SS for children in the Craig et al. (1996) trial treated with speech restructuring, and corresponding scores for a control group. Adapted by permission of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Boberg and Kully (1994) reported marked reductions in stuttering for the six 11–12-year-old participants in their study, which also included adolescents and adults undergoing the same treatment. Prior to treatment, the mean stuttering levels for the six children were 12.9 %SS, which reduced to 1.2 %SS immediately post-treatment. At 4 months post-treatment, levels remained low at 1.8 %SS, and at 1 year post-treatment, the mean level was 2.8 %SS.

Budd et al.’s (1986) intensive programme, which incorporated DAF to train the new speech pattern, also demonstrated positive treatment effects for all the children in the study, some of which were school age. Again assuming these trends represent those for the school-age participants, the pre-treatment stuttering mean was 9.0 percent of total words spoken when talking to parents, reducing to 5.0 percent immediately post-treatment and 5.9 percent at 6 months post-treatment. Druce et al. (1997) reported a marked mean drop of stuttering to 1.8 %SS immediately post-treatment, rising 3.8 %SS at 18 months post-treatment (data specifically for two school-age children).

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

Intensive speech restructuring treatment has some advantages. The intensive training model ensures constant and intentional use of the speech restructuring techniques to promote acquisition of improved fluency, and constant and repetitive practice in theory facilitates change in neural circuitry (Maas et al., 2008). Many clinicians report that it is highly motivating for children and parents to see the rapid change in fluency that intensive programmes usually bring, and this gives them a sense of control and hope.

Intensive speech restructuring programmes can be convenient for children, especially when conducted in a blocked week in school holiday times. Indeed, attrition rates reported in the studies reviewed have been low. Therapy within a group context is a further strength. For the school-age child, group learning is cognitively, behaviourally, socially and educationally salient and promotes naturalistic communication opportunities. Importantly, the group setting can offer a powerful support network and, as such, can facilitate vicarious motor and cognitive learning, as well as desensitisation and disclosure, self-awareness and emotional resilience. Indeed, the emotional support that the group setting offers is valuable at this age, when stuttering-related fears, anxieties and avoidances may have emerged (Guitar, 2006; Murphy et al., 2007).

Disadvantages

However, there are a number of potential shortcomings with using intensive speech restructuring with the school-age child. Our lack of knowledge about what represents the optimal method of intensive speech restructuring means that some programmes (Boberg and Kully, 1994; Craig et al., 1996) generically modify many parameters of the speech process; however, not all children might need all parameters to achieve fluency. Indeed, in Druce’s et al. (1997), therapy was delivered with clinician models with no explicit targets being taught, but it must be remembered that this programme was for younger 6–8-year-old children and the results many not necessarily be generalisable to older children.

The permanency of and neural change and automaticity of the new techniques following a 1-week or 3-week programme has to be questioned, because relapse rates for children following a 1-week programmes can be quite high, as previously discussed (see Craig et al., 1996; Hancock et al., 1998). Possibly, based on the results of (Boberg and Kully, 1994), this may be less of a problem following a 3-week programme.

Another issue is that the cognitive load to learn the complex multi-component processes of restructured speech is very high, as is the demand to summon newly instated fluency techniques in everyday situations. As such, the programmes necessitate high levels of concentration, motivation and commitment in an age group where attentional control and some aspects of insight are not yet fully developed (Weyandt, 2006).

A further barrier is that if a child’s post-treatment speech sounds unnatural, or they perceive it to be unnatural, they will be less likely to use their fluency enhancing speech pattern. Unfortunately, despite the best endeavours with naturalness training and rating scales (Ingham and Onslow, 1985), there is no evidence that children feel that speech with high levels of naturalness does not feel ‘different’ to them.

Intensive speech restructuring programmes for children require clinicians with quite specialised expertise, as well as organisational systems and service providers that support intensive treatment models. Currently, in Australia, there are limited public resources for such programmes in education and child health settings. Added to this, some people might argue that the large number of clinical hours per child is neither time nor cost effective.

From a research perspective, it has been 15 years since the publication of Craig et al.’s (1996) study, and yet there has been no replication of this study for school-age children, either with randomised or non-randomised methods. Gaining a clear understanding of speech restructuring effectiveness with the school-age child has been difficult by the inclusion of unidentified children older than 12 years in studies.

Conclusions and future directions

There is evidence to suggest that intensive speech restructuring programmes have merit for school-age children who stutter. However, stronger and clearer evidence is needed through well-controlled studies that specifically target the 7–12-year-old age group. In addition to addressing issues of how best to facilitate acceptance of a new speech pattern and how best to prevent and manage relapse, further research is required to determine guidelines for using speech restructuring rather than simple operant methods with this age group.

In addition, further exploration is required into the issue of treatment dosage and how intensive does speech-restructuring treatment need to be for children. For example, Craig et al.’s (1996) study involved a semi-intensive arm, and yielded comparable, if not superior, outcomes to the fully intensive programme. Also, we need to understand more about how explicit the restructured treatment targets need to be and how best to teach these. Interestingly, similar to the Camperdown Program, the Druce et al. (1997) treatment entailed no explicit training of multi-component speech targets. Further, it is not clear whether all children need to be taught all parameters of the speech restructuring technique during treatment. Finally, as the difficulties with using brain imaging with children begin to be resolved, research here would be helpful to increase our understanding of how intensive speech restructuring, and other treatments, affect the child’s brain and its structure and function. This could lead to new therapy perspectives and refinements of existing treatments.

Discussion

Ann Packman

One of the pressing things that came up during our discussion was the treatment process. How do you instate the speech pattern, how do you shape, generalise and maintain it? Is a treatment manual available so the current Mater Hospital and University of Queensland3 treatment could be replicated in clinical practice and clinical trials?

Libby Cardell

The manual for the treatment is available and can be purchased from the Mater Hospital in Brisbane.4 Instatement with the speech pattern occurs individually so when children enter the Intensive Phase they can speak stutter-free at 50 SPM or less. I am currently in the process of developing a slightly different manual as well. Our manual continually evolves.

Sheena Reilly

The first thing we would like to ask you about is parent involvement. In the Craig et al. (1996) trial you mentioned two speech-restructuring arms: a 5-day intensive, and a 1 day per week treatment involving parents. We were intrigued that the parent-based programme is not the treatment that you presently give at the University of Queensland, since it had equivalent, if not better, outcomes to the 5-day intensive.

Libby Cardell

Instead of a fully home-based programme, what we do at present is to get the parents more involved than occurs with the more traditional types of speech restructuring programmes. We train the parents as well as the children to do the speech pattern and they are required to practice regularly with their children. Some kind of home component is essential for speech restructuring treatment to work with school-age children.

Joseph Attanasio

You raised the theoretical prospect that the reported success of this treatment with some children is connected with synaptic pruning. We would like to know how you might test any hypotheses that might derive from that position.

Libby Cardell

I am thinking it through now, actually. The manual that I mentioned that I am currently developing is based on motor learning principles.

Joseph Attanasio

But that is programme development. I meant are you planning any research, or can you suggest any research, that would confirm or refute the underlying causes you propose for the effects of this treatment with school-age children.

Libby Cardell

I am thinking a lot about that. I am interested in looking at stuttering during this age range in terms of speech motor development. With a child who is 7 or 8, one assumes that they have developed general motor plans for speech, but there are these little parameters of force, timing and space, perhaps, that are dissociable from that that are somehow being disrupted. I am interested in exploring force, timing and space; those dissociable parameters of generalised motor plans. I am not sure yet how that exploration will occur. I am currently discussing the matter with a colleague at the University of Queensland. Perhaps those who stutter do not always do the same stutter. It may well be that for some, the parameter of force is more of an issue. Perhaps there is a timing versus a space issue. Of course, these are only speech motor concerns. Other points of vulnerability, which I am researching, deal with lexical access using event-related potential. So I am trying to understand the underpinnings at multiple levels. I am just identifying my research areas at present, but am excited about all that potential.

Ann Packman

We were interested that you have such an intensive stage of treatment and whether that is actually necessary. And we were also interested to know how you endeavour to ensure that children continue, during their everyday lives, to use the speech pattern they have learned.

Libby Cardell

Obviously, it comes down much to individual choice with how much children use the speech technique, how much they feel they need to use it and how much they are prepared to use it. But the whole issue of intensity fascinates me, and I am really keen to explore differences between a multiday intensive and an intensive 12-hour day. We need to optimise the acquisition of clinical skills and the use of clinical resources. Additionally, there are models of human learning that would suggest the need for a period to consolidate. Perhaps it would be better to have 2 days, then a break to allow for memory consolidation and whatever, and then maybe another couple of days. Clearly, internalisation for internal control is an important facet of encouraging acquisition and retention in learning. Currently I am discussing this issue with another colleague at the University of Queensland, not just in relation to stuttering, but for dysarthria and apraxia as well.

Ann Packman

Do you have a systematic maintenance programme with regular visits, and do you measure or assess the children’s use of the requisite speech pattern during that period?

Libby Cardell

Yes, definitely. Children and parents can attend for weekly individual sessions or group sessions. With the individual maintenance sessions, they have to bring in recorded evidence of their use of the speech pattern and self-ratings of their stuttering severity in various situations.

Ann Packman

How long is the maintenance programme?

Libby Cardell

We don’t do the performance-contingent type of maintenance that others do. Essentially, as long as the child and parent need external support, we have a policy that ‘the door is never closed’.

Sheena Reilly

I want to go back to the theory issue again. We talked a lot about this and what you described as theory of the treatment mechanism. We wanted to ask you this. Given the rates of relapse of this population in clinical trials – similar to that occurring for adults – could you not simply be teaching compensation methods rather producing motor re-learning?

Libby Cardell

I think that is a fair comment. I described imaging changes in the brains of people who stutter. In one of those studies (Neumann et al., 2005) there was increased left-sided activity immediately after the intensive programme. So is that the effects of compensation or motor learning? The right hemisphere has been found to be more under-activated after these sorts of therapies (Neumann et al., 2003) and so it may be not so much compensation but more motor learning. I think evidence from brain imaging supports that to an extent.

Joseph Attanasio

What is the aim of the programme? Is it to have children become fluent to the point where they don’t depend on a speech technique? Or is it that they must remain somewhat vigilant in order to not stutter?

Libby Cardell

It would be wonderful if there were some way that we could use therapy with this age group while their brains are still plastic so that the amount of attention and vigilance that they have to put into speech, ultimately, is diminished to extremely low levels. Once you get to adulthood or adolescence, really that vigilance never seems to leave the person who stutters. I don’t know the answer to this, so what I will say is that if there is a way, and if it is related to treatment intensity and neurobiology, I think, at least, we have to start to think about that. Being able to rewire the brain in a positive way at a younger age will mean less of that vigilance later during life. That whole area needs research.

Ann Packman

Our group was interested to find out what you think are the active components of the treatment, because there seem to be many components.

Libby Cardell

I think that obviously the slowed rate is a key factor. I believe that what we call ‘chunking’ is a big factor too because that allows children to plan what to say next and to keep their thoughts a lot more organised, and possibly to settle the brain back to a resting level before speaking again. ‘Blending’, as we call it, is very important but probably one of its most important aspects are gentle onsets and easing into phrases.

Ann Packman

And how do you think the anxiolytic component of the treatment contributes?

Libby Cardell

This is of course a critical research area. For now, however, I have an intuitive clinical belief that the anxiolytic procedures and cognitive restructuring contributes to anxiety reduction and avoidance reduction. But the contribution of these features to documented treatment effects in children is yet to be known.

Sheena Reilly

Can all 7–12-year olds cope with 5 days of 8-hour treatment per day?

Libby Cardell

It does require a certain degree of readiness and aptitude from the children and there are some for whom this treatment is not appropriate.

Sheena Reilly

So who are the children for whom you would not recommend it? That is the critical issue.

Libby Cardell

Children who have significant language or speech problems as well as stuttering. Also, children who have hyperactivity deficits. But not necessarily children who are slower to learn because what we have found is that the initial learning of the speech technique can occur individually in our programmes so they can have the time to take longer to learn. We have flexibility with the programme as well where the children with other issues might attend for perhaps 3 days for shorter hours with fewer demands in terms of the transfer tasks and possibly more time spent on the actual instatement. We don’t want to exclude any child.

References

Andrews, G., Guitar, B., & Howie, P. (1980) Meta-analysis of the effects of stuttering treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 45, 287–307.

Andrews, G., Craig, A., Feyer, A.-M., Hoddinot, S., Howie, P., & Neilson, M. (1983) Stuttering: a review of research findings and theories circa 1982. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48, 226–246.

Bakhtiar, M., & Packman, A. (2009) Intervention with the Lidcombe Program for a bilingual school-age child who stutters in Iran. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 61, 300–304.

Bernstein-Ratner, N. (2010) Translating recent research into meaningful clinical practice. Seminars in Speech and Language, 31, 236–249.

Block, S., Onslow, M., Packman, A., Gray, B., & Dacakis, G. (2005) Treatment of chronic stuttering: outcomes from a student training clinic. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 40, 455–466.

Boberg, E., & Kully, D. (1994) Long-term results of an intensive program for adults and adolescents who stutter. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 1050–1059.

Bothe, A. K., Davidow, J. H., Bramlett, R. E., & Ingham R. J. (2006) Stuttering treatment research 1970–2005: I. Systematic review incorporating trial quality assessment of behavioral, cognitive, and related approaches. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 321–341.

Braun, A. R., Varga, M., Stager, S., Schultz, G., Selbie, S., Maisog, J. M., & Ludlow, C. L. (1997) Altered patterns of cerebral activity during speech and language production in developmental stuttering. An H2(15)O positron emission tomography study. Brain, 120, 761–784.

Budd, K. S., Madison, L. S., Itzkowitz, J. S., George, C. H., & Price, H. A. (1986) Parents and therapists as allies in behavioural treatment of children’s stuttering. Behaviour Therapy, 17, 538–553.

Carey, B., O’Brian, S., Onslow, M., Block, S., Packman, A., & Jones, M. (2010) Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial of a telehealth treatment for chronic stuttering: the Camperdown Program. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 45, 108–120.

Chang, S. E., Erickson, K. I., Ambrose, N. G., Hasegawa-Johnson, M. A., & Ludlow, C. L. (2008) Brain anatomy differences in childhood stuttering. Neuroimage, 39, 1333–1344.

Chechik, C., Meliljson, I., & Ruppin, E. (1998) Synaptic pruning in development: a computational account. Neural Computation, 10, 1759–1777.

Couperus, J. W., & Nelson, C. A. (2006) Early brain development and plasticity. In: K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development (pp. 85–105). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Craig, A. (2010) Smooth speech and cognitive behavioural therapy. In: B. Guitar & R. McCauley (Eds.), Treatment of Stuttering: Established and Emerging Interventions (pp. 188–214). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Craig, A., Feyer, A. M., & Andrews, G. (1987) An overview of a behavioral treatment for stuttering. Australian Psychologist, 22, 53–62.

Craig, A., Hancock, K., Chang, E., McCready, C., Shepley, A., McCaul, A., & Reilly, K. (1996) A controlled clinical trial for stuttering persons aged 9 to 14 years. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 808–826.

De Nil, L. F. (1999) Stuttering: a neurophysiological perspective. In: N. Bernstein-Ratner & C. Healey (Eds.), Stuttering Research and Practice: Bridging the Gap (pp. 85–102). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

De Nil, L. F., Kroll, R. M., Lafaille, S. J., & Houle, S. (2003) A positron emission study of short- and long-term treatment effects on functional brain activation in adults who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 28, 357–380.

Druce, T., Debney, S., & Byrt, T. (1997) Evaluation of an intensive treatment program for stuttering in young children. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 22, 169–186.

Fox, P. T., Ingham, R. J., Ingham, J. C., Hirsch, T. B., Downs, J. H., Martin, C., & Lancaster, J. L. (1996) A PET study of the neural systems of stuttering. Nature, 382, 158–162.

Goldiamond, I. (1965) Stuttering and fluency as manipulatable operant treatment classes. In: L. Krasner & L. Ullmann (Eds.), Research in Behavior Modification (pp. 106–156). New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Guitar, B. (2006) Stuttering: An Integrated Approach to its Nature and Treatment (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Guitar, B., & McCauley, R. (2010) Treatment of Stuttering: Established and Emerging Interventions. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Hancock, K., & Craig, A. (1998) Predictors of stuttering relapse one year following treatment for children aged 9 to 14 years. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 23, 31–48.

Hancock, K., Craig, A., Campbell, K., Costello, D., Gilmore, G., McCaul, A., & McCready, C. (1998) Two to six year controlled trial stuttering outcomes for children and adolescents. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 41, 1242–1252.

Harrison, E., Onslow, M., Andrews, G., Packman, A., & Webber, M. (1998) Control of stuttering with prolonged speech: development of a one-day instatement program. In: A. Cordes and R. Ingham (Eds.), Treatment Efficacy in Stuttering (pp. 191–212). San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group.

Ingham, R. J. (1984) Stuttering and Behavior Therapy. San Diego, CA: College Hill.

Ingham, R. J., & Andrews, G. (1973) Details of a token economy stuttering therapy for adults. Australian Journal of Human Communication Disorders, 1, 13–20.

Ingham, R. J., & Onslow, M. (1985) Measurement and modification of speech naturalness during stuttering therapy. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 50, 261–281.

Kleim, J. A., & Jones, T. A. (2008) Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: Implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51, S225–S239.

Kolb, B. (1995) Brain Plasticity and Behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Koushik, S., Shenker, R., & Onslow, M. (2009) Follow-up of 6–10-year old stuttering children after Lidcombe Program treatment: a Phase 1 trial. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 34, 279–290.

Lincoln, M., Onslow, M., Lewis, C., & Wilson, L. (1996) A clinical trial of an operant treatment for school-age children who stutter. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 5, 73–85.

Ludlow, C. L., Hoit, J., Kent, R., Ramig, L. O., Shrivastav, R., Strand, E., & Sapienza, C. M. (2008) Translating principles of neuroplasticity on speech motor control and recovery. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51, S240–S258.

Maas, E., Robin, D. A., Austerman Hula, S. N., Freedma, S. K., Wulf, G., Ballard, K. J., & Schmidt, R. A. (2008) Principles of motor learning in treatment of motor speech disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 277–298.

Menzies, R., Onslow, M., Packman, A., & O’Brian, S. (2009) Cognitive behavior therapy for adults who stutter: a tutorial for speech-language pathologists. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 34, 187–200.

Murphy, W. P., Yaruss, J. S., & Quesal, R. W. (2007) Enhancing treatment for school-age children who stutter I. Reducing negative reactions through desensitization and cognitive restructuring. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 32, 121–138.

Neumann, K., Euler, H. A., Wolff von Gudenberg, A., Giraud, A. L., Lanfermann, H., Gall, V., & Prebisch, C. (2003) The nature and treatment of stuttering as revealed by fMRI: A within- and between group comparison. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 28, 381–410.

Neumann, K., Prebisch, C., Euler, H. A., Wolff von Gudenberg, A., Lanfermann, H., Gall, V., & Giraud, A. L. (2005) Cortical plasticity associated with stuttering therapy. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 30, 23–39.

Nippold, M. A. (2011) Stuttering in school-age children: a call for treatment research. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 99–101.

O’Brian, S., Onslow, M., Cream, A., & Packman, A. (2003) Camperdown Program: outcomes of a new prolonged speech treatment model. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 46, 933–946.

Onslow, M., Costa, L., Andrews, C., & Harrison, E. (1996) Speech outcomes of a prolonged speech treatment for stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 734–739.

Onslow, M., Jones, M., O’Brian, S., Menzies, R., & Packman, A. (2008) Defining, identifying, and evaluating clinical trials of stuttering treatments: a tutorial for clinicians. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 401–415.

Schmidt, R. A. (1975) A schema theory of discrete motor skill learning. Psychological Review, 82, 225–260.

Sowell, E. R., Thompson, P. M., Leonard, C. M., Welcome, S. E., Kan, E., & Toga, A. W. (2004) Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 8223–8231.

Watkins, K. E., Smith, S. M., Davis, S., & Howell, P. (2008) Structural and functional abnormalities of the motor system in developmental stuttering. Brain, 131, 50–59.

Webster, R. L. (1980) Evolution of a target-based behavioral therapy for stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 5, 303–320.

Weyandt, L. N. (2006) The Physiological Bases for Cognitive and Behavioural Disorders. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Wingate, M. E. (1975) Stuttering: Theory and Treatment. New York: Irvington.

1 The Onslow et al. report included two school-age children but it is not possible to identify their data in the report.

2 One was almost 7 years, at 6 years 9 months.

3 Associate Professor Cardell currently conducts the treatment at, and in conjunction with, the University of Queensland. She will be conducting this treatment through Griffith University, as well.

4 Readers wishing to do so can contact Associate Professor Cardell at e.cardell@griffith.edu.au.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree