Chapter 10 International and intercultural aspects of voice and voice disorders

Background

During the period of July to December 2009, 60 questionnaires were electronically sent out to voice specialists all over the world to survey voice assessment and diagnosis, voice education and training, and voice clinic practice profiles. The rate of return was 76.6% sampled over 26 countries. The goal was to obtain data on the variety of approaches to the training of voice therapists and the manner in which they offer assessment and treatment of voice disorders. The questionnaire and results are given in Appendix 10-1 at the end this chapter. The information from the survey is used throughout this chapter to show the international and cultural issues in understanding voice and its disorders.

Beginning of an intercultural relationship

The information in this chapter evolved through multiple streams. One stream, the visual stream, was initiated by Moore and Von Leden, who sought to understand the diagnosis of voice problems in more detail and to identify methods that may be used to treat the problems (Cooper & Von Leden, 1996; Moore, 1998). Their work in the 1940s and 1950s remains a guide to the importance of a team approach.

As speech pathologists, we have traditionally used the auditory sense to provide treatment. We have learned the importance of listening because the visual information is not always present and was rarely present when the field of speech pathology was in its infancy. Moreover, voice therapy involves a strong auditory-perceptual basis for changing vocal behavior. As listeners, we have learned to pay attention initially to the articulation, accent, or speed of a talker rather than his or her voice. Only when the voice falls out of the range that we consider normal do we focus on the vocal characteristics of the speaker. For that reason, the early work of Shipp and associates must be acknowledged. They began to examine the characteristics of normal voices in the late 1960s (Shipp & Hollien, 1969). They were interested in identifying the healthy voice and in how healthy voices vary with age. They found that listeners had little difficulty categorizing age simply by listening to a sample of the voice. Later, they pointed out the importance of the fundamental frequency as an indicator of age (Hollien & Shipp, 1972), with a gap of 5 years of certainty. Thus, the voice gives us much more information than simply a message. The message is steeped with information about the speaker as well as the context of the message. We are well aware of the need to understand the normal voice and its multiple messages. Germinal work, such as the studies by Hollien and Shipp, has propelled clinicians and scientists all over the world to search for a better understanding of vocal fold vibration, of the characteristics of the normal voice, and of the degree to which the voice can be developed, trained, and improved.

The second stream of knowledge independently evolved from the work of individuals such as Black and Tosi, which has culminated in a seminal work on voice identification (Tosi, 1979). Their interests, along with determining how to assess normal from abnormal, were focused on how the ear perceives severity and what instruments besides the ear can best measure the changes in severity of the pathologic voice. Thus, the two areas of laryngeal visualization and psychoacoustics have brought together the modern voice specialist’s approach to voice disorders. This chapter updates the degree to which those two streams of evidence have evolved over the years and throughout many countries.

Dimensions of voice production

Traditional definition of the normal voice

In the narrowest sense, a normal voice is the result of an air stream driving the vocal folds into vibration through a series of resonance chambers. Conversely, in a broader sense, voice is one of the most important expressions of a human being and his or her culture. It is very difficult to draw a definite boundary to classify normal and abnormal samples because voice is not a descriptive category (like male and female). Instead, it is a series of measures (like weight and height) that can vary from more to less, depending on the subject characteristics, spoken language, occupational demands, and environmental factors. A voice is usually considered normal when it properly represents a person; corresponds to the expectations of the person’s gender, age, group, occupation, society, and community; and does not call attention to itself. An abnormal voice is one that impairs communication or reduces voice-related quality of life (Schwartz et al., 2009). Therefore, the social and professional aspects of someone’s life may be vocally at risk because of the way he or she sounds or the effort needed to produce sound.

Range of abnormal or dysphonic voice

A voice can be considered dysphonic when an alteration in its production impairs social and professional communication (Schwartz et al., 2009). Some patients can have complaints of vocal quality (hoarseness, breathiness, or tension), some others can have pitch deviations (too high, too low, or monotone voice), whereas some others do not have clear auditory deviations but a sense of effortful phonation, which can clearly limit communication performance. A diagnostic assessment is performed, preferably with information from the physician and speech-language pathologist (SLP). Therefore, this label of abnormal or dysphonic should only be used after a proper medical evaluation.

The disordered voice may be an exclusive result of vocal behavior or a partial result of that behavior. If vocal behavior is abusive, overly driven, or combined with injuries to other systems (pulmonary, neurologic, digestive), lesions, usually benign in nature, may result. In some situations, the relationship between the use of voice and the voice disorder is evident both to the clinician and to the patient. In other circumstances, this relationship is not very straightforward. The patient and the clinician must understand the importance of the vocal behavior as a contributor to the genesis of the dysphonia. Designing a therapeutic program to define the intervention options and also to reestablish an acceptable voice is an educational and therapeutic contract between the clinician and the patient. Stress related to communication in different cultural settings can play a major role in the development of a vocal problem; thus, the reduction of stress may help in rehabilitation of the voice problem.

The artistic voice

Singing is one of the best expressions of a culture. The artistic voice serves both to represent a culture and to convey the singer’s personality. Some cultural expressions may amplify certain vocal traits. For example, Hamdan and colleagues (2008) studied 78 Middle Eastern singers and concluded that this specific and very admired singing style, with a rich musical mode (Maqam system), is characterized by moderate tension, hypernasality, and thoracic breathing. This combination of features is different from Western singing, which is characterized by balanced tension, oral resonance, and abdominal breathing, particularly for the operatic singers. So, even if the Arabic singing voices are somehow displaced toward the region of deviated voices, it does not reflect pathology but rather expresses different vocal characteristics valued differently in the culture.

Voice as a cultural construct

Only recently, specific books produced by SLPs have addressed the issue of voice as a contributor to reduce accent in English and produce a better interaction between articulation and phonation (Menon, 2007). Although this work often goes undocumented, there are many anecdotal reports of the changes in voice following singing in the Russian opera literature, singing in the Indian movie industry (Bollywood), and acting in roles requiring the use of Asian cultural intonation. Not only are these cultural differences important in the acting world, they also reflect how the average listener perceives normal and dysphonic voices of various cultures.

Prevalence of voice disorders

General findings

Prevalence data on voice disorders are difficult to obtain. Demographic variation is largely due to country (even regions), age, gender, ethnicity, and occupation. Even where prevalence data are available, comparisons among studies are difficult owing to different sampling techniques, tools for assessment, and statistical power. Many issues are related to this difficulty. Normal voice is a negotiable concept, and there is no clear indication to establish what is a voice problem. Moreover, vocal style and vocal behavior may vary, largely owing to cultural expression, and this can interfere with a vocal screening program. Above all, well-designed prevalence studies are still limited in our specialty. The belief is that prevalence of voice disorders appears to vary widely across the spectrum of countries. Several studies have reported the prevalence of voice disorders in various countries and cultures, but most of the data come from evaluation of school-aged children.

According to two recent epidemiologic studies done in the United States, nearly one third of the population may experience impaired voice production at some point in their lives (Roy, 2004a; Roy et al., 2005). Data from the United Kingdom obtained during the past 20 years (Carding & Hillman, 2001) indicate prevalence ranging from 28 per 100,000 population in 1986 (Enderby & Phillipp, 1986), to 89 per 100,000 population in 1995 (Enderby & Emerson, 1995), to 121 per 100,000 population in 2001 (Mathieson, 2001). Although this trend suggests an increase of voice disorders during the past 25 years, it may simply represent more accurate sampling and reporting from a broader-based network.

In the United States, the general prevalence of a vocal problem has been estimated to be about 6.6% in adults (Roy et al., 2005), with a high lifetime prevalence of voice complaints of 28.8% in the general population (Roy et al., 2004a). Some professionals worldwide, such as teachers, are recognized as having the highest prevalence rates of vocal problems, reaching up to 57% and 3.87 new cases per year per 1000 teachers (Preciado-Lopez et al., 2007). Telemarketers, aerobic instructors, sport coaches, military personnel, and ministers generally have the highest prevalence of voice disorders after teachers. In addition, older adults are also at particular risk, with a prevalence of 29% (Roy et al., 2007), and a lifetime incidence of up to 47% (Roy et al., 2007) was found in groups of patients older than 55 years.

Women are more frequently affected by voice disorders than men, with a 6:4 female-to-male ratio (Coyle et al., 2001; Roy et al., 2005; Titze et al., 1997). Among children, prevalence rates vary from 3.9% to 23.4% (Duff et al., 2004; Silverman & Zimmer 1975), with the most affected age range being 8 to 14 years (Angelillo et al., 2008). This large range may be due to the screening protocol, to the type of testing used for the analysis (perceptual analysis only, visual inspection of the larynx, patient complaints), and to the threshold level set for failing. Data show that African American and European American students present similar rates of dysphonia (Duff et al., 2004).

Specific findings

Children with voice disorders

The prevalence of voice disorders in children has been estimated to be between 6% and 9% during the past 25 years. Results of studies vary, but in children up to the age of 14 years, the prevalence is about 6 in 100, or 6% (Leske, 1981). This apparently decreases during adulthood, ages 15 to 44 years, when the incidence is reported to be as low as 1% of the population, and then increases to 6.5% in those 45 to 70 years old. Although these numbers may be low, they reflect reporting in medical settings, and one should consider that many voice disorders, such as mild hoarseness or breathiness, go untreated or even unnoticed for years. This is especially true in countries where the health care is limited to serious, life-threatening illnesses.

Senturia and Wilson (1968) reported that 6% of school-aged children in a Midwest city in the United States had a voice disorder. Others have reported the prevalence to be more in the range of 6% to 9%, with one study (Silverman & Zimmer, 1975) reporting 4% of school-aged children with a voice disorder. Duff and colleagues (2004), in a study of 2445 African American and European American preschool children (1246 males and 1199 females, aged 2 to 6 years), found that only 3.9% of African American and European American preschoolers interviewed by SLPs had a voice disorder. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences for age, gender, or race.

Adults with voice disorders

Prevalence of voice disorders in the adult population appears to vary based on the presence of other diseases. According to a study by Verdolini and Ramig, about 30% of working adults will experience a voice disorder during some time in their lives (Verdolini & Ramig, 2001).

The most common group of individuals who experience voice disorders consists of teachers (Roy et al., 2005). Roy reported that more than 3 million teachers in the United States use their voice as a primary tool of trade and are thought to be at higher risk for occupation-related voice disorders than the general population. However, estimates regarding the prevalence of voice disorders in teachers and the general population vary considerably. Roy and associates (2004b) found that the prevalence of teachers reporting a current voice problem was significantly greater compared with nonteachers. In their study, 11% of the teachers had a current voice problem, and 57% of the teachers indicated that they had a voice problem at some time in their lives. That is compared with only 28% of nonteachers reporting a voice problem at some time in their lives. Compared with men, women not only had a higher lifetime prevalence of voice disorders (46.3% vs. 36.9%) but also had a higher prevalence of chronic voice disorders (>4 weeks in duration), compared with acute voice disorders (20.9% vs. 13.3%). The same Roy study was replicated in Brazil (Behlau et al., 2011), in which data from 26 Brazilian states were gathered and analyzed including 3265 individuals consisting of 1651 teachers and 1614 nonteachers. Several similarities were found, despite deep economic, social, and cultural differences between the two countries. The Brazilian teachers reported a higher number of current (3.7) and past (3.6) voice symptoms when compared with nonteachers (1.7 present, 2.3 past) and attributed these to their occupation (P < .001). Sixty-three percent of teachers (1041) and 35.3% of nonteachers (569) reported having suffered a voice problem at some time in their life. Teachers missed more work days than nonteachers (4.9 days for voice problems). Teachers indicated the possibility of changing their occupation in the future because of their voice more than nonteachers (276, or 16.7%, and 14, or 0.9%; P < .001). Regional characteristics were not significantly different, with the two exceptions of more symptoms in dry regions than in humid areas and more access to medical and rehabilitative services in rich states than in poor regions. This disturbing panorama was consistent all over Brazil and similar to the United States, which reveals the strength and uniformity of data.

Laryngeal cancer: a special case

Although few prevalence data exist for specific voice problems, the best available data are on the incidence of laryngeal cancer. In 2009, the American Cancer Society reported 12,290 new cases of laryngeal cancer, 3660 deaths from laryngeal cancer, and 2850 new cases of hypopharyngeal cancer (American Cancer Society, 2010). The agency indicated that these numbers are decreasing in the United States owing to the reduction in smoking. Conversely, it suggests these numbers are increasing in countries where smoking is stable or increasing, such as Russia, China, and Greece.

The International Agency of Research on Cancer (Parkin, 2004) recently reported an estimated 161,000 new cases of laryngeal cancer per year, which can lead to a severe vocal limitation, particularly when diagnosis is delayed and treatment requires total ablation of the larynx (including the vocal folds). Laryngeal cancer is a predominantly male cancer, and it represents 2.7% of all cancer cases. The sex ratio (more than 7:1 male-to-female ratio) is greater than for any other site. For men, the high-risk world areas are Europe (East, South, and West), South America, and Western Asia. In Western Asia, larynx cancer accounts for more than 5% of cancers in men. Tobacco smoking is estimated to cause two thirds of all cancer cases in men. The risk for cancer development is the combined results of the relative contributions of “environment” and “genetics,” which can at least partially explain some prevalence peaks in certain countries or areas of the globe, such as India and Brazil. The variation in exposure to carcinogens, pollution in the external environment, and lifestyle choices (tobacco and alcohol consumption) are the three factors contributing to cancer in the head and neck areas. This so-called triangular hypothesis plays a major role in countries where tobacco restriction laws are not reinforced. The Brazilian Academy of Laryngology and Voice (http://www.ablv.com.br) states that Brazil (São Paulo city) occupies the second worldwide position on laryngeal cancer, after India (Mumbai), and reinforces the need to consider hoarseness as a threatening symptom. The World Voice Day, an initiative that started in Brazil in 1999 and has quickly spread internationally, has one of its main goals to reduce this alarming trend (Švec & Behlau, 2007).

Laryngeal cancer is not the only form of cancer that impairs normal voice communication. Oral cavity cancer accounted for 267,000 cases in 2000 in the United States (Parkin, 2004). Almost two thirds of those cases were in men. The geographic area with the highest incidence is Melanesia (36.3 per 105 in men and 23.6 per 105 in women). Similar to laryngeal cancer, rates of oral cancer in men are higher than in women in most regions, such as Western (12.5 per 105) and Southern Europe (9.2 per 105), South Asia (13.0 per 105), Southern Africa (12.4 per 105), and Australia and New Zealand (12.1 per 105). However, in females, the incidence is relatively high in Southern Asia (8.6 per 105).

Prevalence summary

The issue of prevalence is highly variable across cultures. To some extent, it is based on the manner in which prevalence is identified. Several studies have focused on voice qualities and how they affect the presence or absence of a voice disorder. The incidence of voice disorders increases when one considers the effects of conditions such as cerebral vascular accidents, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurologic and neuromuscular diseases, primarily in aging adults, that often bring on changes in the voice that affect one’s ability to communicate. The most studied and treated neuromuscular disorder with vocal impairment is surely Parkinson’s disease (Sapir et al., 2009), affecting an estimated 8 million individuals in the world; of these, 80% to 90% are likely to develop speech disorders (dysarthria), in which reduced voice loudness and monotone are the primary voice characteristics.

Assessment of voice disorders

Self-assessment tools

The World Health Organization Quality-of-Life (WHO QOL) assessment group proposed that the perceptions and interpretations of an individual’s QOL are rooted in that person’s culture (Skevington, 2002). The cultural background of an individual may influence the manner in which a person experiences a voice disorder (Krischke et al., 2005). These cultural constraints, coupled with limited social interactions, can produce different strategies in interpreting and coping with a voice problem.

Traditionally, assessment of voice disorders has focused on attempts to measure the vocal output. This assessment strategy remains prominent to this day. In the early 1980s and 1990s, the main efforts for assessment of the voice-related outcomes were directed to the development and improvement of computerized objective analysis of acoustic and aerodynamic measures. However, these objective measures did not consider the patient’s perspective regarding his or her vocal function. Similarly, improved and magnified endoscopic images of the larynx, including stroboscopic images, have been used to diagnose and assess vocal function in diseased and post-treatment states (Woo, 1996). However, neither objective voice measures nor video endoscopic measures have been shown to be useful in assessing the patient’s feelings about the severity of either their voice problem or their satisfaction with the outcomes of their treatments (Jacobson et al., 1997).

Voice handicap index

Several self-evaluation protocols have been developed and disseminated worldwide for understanding the patient’s perception of the impairment, disability, and handicap. In 1997, a group from the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit developed an assessment tool to focus on the patient’s perception of the severity of his or her voice: the Voice Handicap Index (VHI; Jacobson et al., 1997). The VHI is a patient self-administered assessment of voice handicap. It has been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument for assessing patients’ self-perceived voice handicap. A handicap, as described by the WHO, is a social, economic, or environmental disadvantage (WHO, 1980). This is the result of an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfillment of one or several roles regarded as normal, depending on age, sex, and social and cultural factors (Barbotte et al., 2001). The term disability refers to a restriction or lack of ability to perform a daily task. Therefore, the handicap associated with a voice disorder cannot be fully assessed by either objective voice measurements or videoendo- scopic measurements. Rather, the measurement of a patient’s handicap due to a voice disorder must take into account social and cultural factors, such as whether a teacher can teach all day and throughout the week or whether a factory foreman can talk loudly enough to be heard over the noise of factory machines.

The VHI was acknowledged by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) as a reliable and valid diagnostic tool. Since then, the VHI has been translated and adapted to many different languages. Table 10-1 lists current references to the adapted and validated VHI.

TABLE 10-1 Countries where the Voice Handicap Index Is Used as a Valid and Reliable Tool for Self-Assessment of the Severity of the Voice Disorder

| Country | Study Authors, Year |

|---|---|

| United States | Jacobson, Johnson, Grywalsky, Silbergleit, Jacobson, Benninger, Newman, 1997 |

| Germany | Nawka, Wiesmann, Gonnermann, 2003 |

| Taiwan | Hsiung, Lu, Kang, Wang, 2003 |

| Portugal | Guimarães, Aberton, 2004 |

| France | Woisard, Bodin, Puech, 2004 |

| Poland | Pruszewicz, Obrebowski, Wiskirska-Woznica, Wojnowski, 2004 |

| United Kingdom | Franic, Bramlett, Bothe, 2005 |

| Germany | Günther, Rasch, Klotz, Hoppe, Eysholdt, Rosanowski, 2005 |

| The Netherlands | Hakkesteegt, Wieringa, Gerritsma, Feenstra, 2006 |

| Israel | Amir, Ashkenazi, Leibovitzh, Michael, Tavor, Wolf, 2006 |

| Scotland | Webb AL, Carding PN, Deary IJ, MacKenzie K, Steen IN, Wilson, 2007 |

| Spain | Núñez-Batalla, Corte-Santos, Señaris-González, Llorente-Pendás, Górriz-Gil, Suárez-Nieto, 2007 |

| Turkey | Kiliç, Okur, Yildirim, Ogˇüt, Denizogˇlu, Kizilay, Ogˇuz, Kandogˇan, Dogˇan, Akdogˇan, Bekirogˇlu, Oztarakçi, 2008 |

| Sweden | Ohlsson, Dotevall 2009 |

| Italy | Schindler, Ottaviani, Mozzanica, Bachmann, Favero, Schettino, Ruoppolo, 2010 |

| Greece | Helidoni, Murry, Moschandreas, Lionis, Printza, Velegrakis, 2010 |

| Saudi Arabia | Malki, Mesallam, Farahat, Bukhari, Murry, 2010 |

| Brazil | Behlau, Alves dos Santos, Oliveira, 2011 |

It is interesting to note that there are only five comments on validation particularities. The Brazilian group mentions that the VHI presented a higher linguistic challenge because of similarities in some of the sentences (Behlau et al., 2009). In European Portuguese, one word did not achieve direct translation and had to be adapted (Guimarães & Aberton, 2004). The French version was appointed as deserving a review in translation (Woisard et al., 2004). The German modification may not represent all statements equally (Günther et al., 2005); and the Polish version has suffered modifications as well (Pruszewicz et al., 2004).

Despite its wide clinical and research application, the reliability of the VHI was questioned when being correlated with objective voice laboratory measurements (Hsiung et al., 2002). Hsiung and coworkers (2002) reported a large discrepancy between the results of VHI and voice laboratory measurements testing. Accordingly, they concluded that no objective parameter can yet be regarded as a definitive prognostic factor in a subjective evaluation of dysphonic patients.

A recent study showing the strength of the VHI was published by Verdonck-de Leeuw and colleagues (2008) using confirmatory factor analysis to assess equivalence of the American version and several translations, including Dutch, Flemish Dutch (Belgium), Great Britain English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Swedish. VHI questionnaires were gathered from a cohort of 1052 patients from eight countries. They found that the internal consistency of the VHI proved to be good. Confirmatory factor analysis across countries revealed that a three-factor fixed-measurement model was the best fit for the data. The three subscales appeared to be highly intercorrelated, especially in the American data. The underlying structure of the VHI was also equivalent regarding various voice lesions. Distinct groups were recognized according to the severity of the VHI scores, indicating that various voice lesions lead to a diversity of voice problems in daily life. Verdonck-de Leeuw and colleagues concluded that the American Voice Handicap Index and the translations studied appeared to be equivalent. This would suggest that results from studies from the various countries included can be compared.

Although the VHI may be the only reliable and valid assessment tool used worldwide, investigators have found some discrepancies in the country-to-country data. Thus, whereas the internal consistency appears to be high from country to country, terminology across certain questions may reflect some of the difficulties that persist when trying to validate any test across countries and cultures. Cultural variations exist in every language and in the interpretation of specific words. For example, the terms handicap and creaky proved difficult to translate into the Greek version of the VHI (Helidoni et al., 2010). The Arabic version from Saudi Arabia went through an exhaustive review before publication because many Arabic countries use some modification of the Arabic language of Saudi Arabia (Malki et al., 2010). Nonetheless, the Arabic VHI has been shown to be highly reliable and related to the original VHI for the Saudi Arabian population.

One problem that may arise with the use of the VHI is due to its length. In routine diagnostics, voice patients may need to undergo several measurements. Therefore, the 30 items of the VHI might require too much time (about 10 to 15 minutes). For this reason, two shortened versions of the VHI have been proposed: the VHI-10 (Lam et al. 2006; Rosen et al., 2004) and the VHI-12 (Nawka et al., 2009). The VHI-10 has been constructed by selecting those items that have the largest differences between patients and a control group as well as between pretreatment and post-treatment (Rosen et al., 2000; 2004). The VHI-12 is based on factors with test-retest validation. Both scales have already been applied in numerous clinical studies around the world. However, each of these short scales was only constructed on the basis of data from the United States and using American English. The VHI-12 was from a subject sample from Germany using the German language.

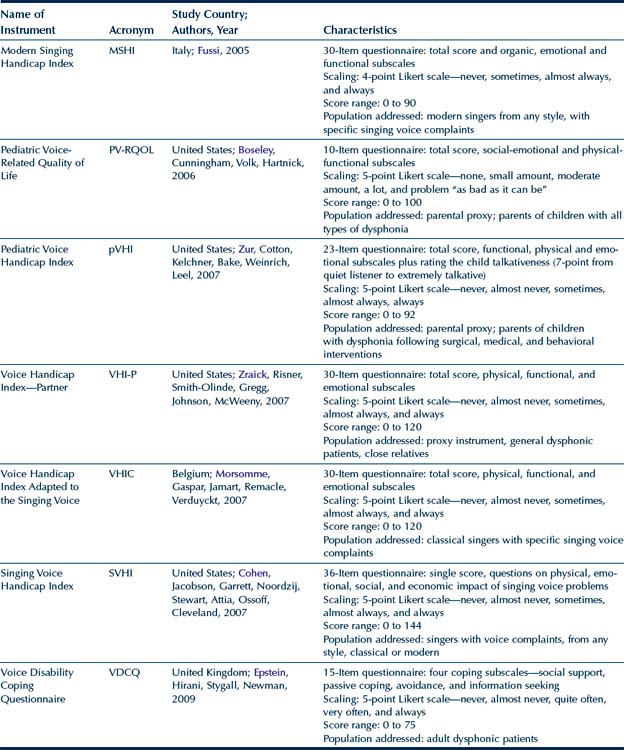

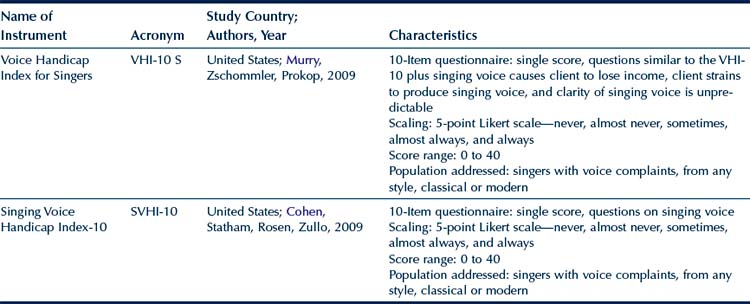

To address the population of professional singers, VHI adaptations for assessing singing voice were proposed (Cohen et al., 2007; Morsomme et al., 2007), including a short version, the SVHI-10 (Cohen et al., 2009). An Italian phoniatrician, Franco Fussi, proposed two versions after analyzing more than 400 singers, called the Modern Singing Handicap Index (MSHI) for popular singers and the Classical Singing Handicap Index (CSHI) for classical singers (Fussi, 2005). Fussi showed that singers do respond to specific questions related to their vocal health and work status. These protocols have been used in the United States (Cohen et al., 2007), Belgium (Morsomme et al., 2007), Italy (Fussi, 2005), Spain (García-López et al., 2010), and Brazil (Moreti et al., 2010), with benefits to both the singer and the SLP. Results are comparable among the cultures, despite different singing styles. The Fussi modern and classical singing versions have been translated and adapted in Brazil (Moreti et al., 2010) after analyzing data from 229 singers (170 popular and 59 classical). Classical singers with voice complaint had higher scores than the popular singers. Classical singers with voice complaint seem to perceive a higher impact on quality of life due to their problem, reflecting a greater sensitivity to the dysphonic condition. The organic aspects showed the greatest deviations for the popular singers. The classical singers with and without vocal complaint had greater deviations than the popular singers on both the organic and functional aspects. Both protocols proved to be a useful tool for helping SLPs, singing teachers, and conductors to map voice problems of popular and classical singers. These data suggest that modern and classical singers deserve to be evaluated with specific protocols. Although there are currently no data to compare singers from all over the world, one might hypothesize that differences between classical and modern seem to follow a general trend and are not culturally bound.

Recently, the VHI-10 was adapted to the professional singer (Murry et al., 2009). Data from singers and nonsingers were analyzed in terms of overall subject self-rating of voice handicap and then rank-ordered from least to most important. The overall difference between the mean VHI-10s for the singers and nonsingers was not statistically significant, thus supporting the validity of the VHI-10. However, the 10 statements were ranked differently in terms of their importance by both groups. In addition, when three statements related specifically to the singing voice were substituted in the original VHI-10, the singers judged their voice problem to be more severe than when using the original VHI-10. Thus, the type of statements used to assess self-perception of voice handicap may be related to the subject population. Singers with voice problems do not rate their voices to be more handicapped than nonsingers unless statements related specifically to singing are included.

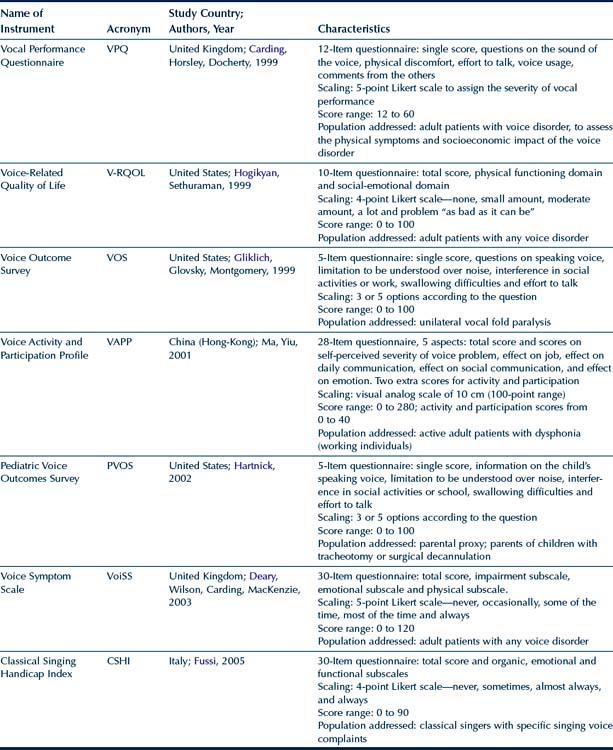

Other assessment tools

Other self-assessment tools have been developed recently. Most of these came from the initial American efforts in trying to quantify vocal handicap or quality of life, such as the specific Italian protocols to assess modern and classical singers (MSHI and CSHI; Fussi, 2005), and some others are country based, such as the Hong Kong protocol to assess voice activity and participation (VAPP; Ma & Yiu 2001). Others focus on specific aspects, such as the British protocol to evaluate vocal performance (VPQ; Carding et al., 1999) and the British coping questionnaire to assess the strategies used to deal with a voice problem (VDCQ; Epstein et al., 2009). Table 10-2 summarizes the major instruments to address self-perceived voice handicap and voice-related quality of life.

Most of the tools in Table 10-2 are less widely used than the VHI. The V-RQOL measure is a 10-item, disease-specific outcome instrument for voice disorders. All items are straightforward and easily translated and were validated in Brazilian Portuguese (Gasparini et al., 2009). The V-RQOL has a physical functioning domain, a social-emotional domain, and a total score. The VAPP (Ma & Yiu, 2001), originally written in English with data from a Hong Kong population, is a 28-item assessment tool that evaluates the perception of a voice problem, activity limitation, and participation restriction based on the International Classification of Functioning concept of WHO. It consists of five sections: self-perceived severity of voice problem, effect on job, effect on daily communication, effect on social communication, and effect on emotion. The VAAP is a valid tool available in Finnish (Sukanen et al., 2007) and Brazilian Portuguese (Behlau et al., 2009). Because of this specific configuration, the VAPP helps to obtain a map on the scenario where the voice problem interferes the most (on the job, daily communication, social communication, and effect on emotion).

Each protocol to assess the impact of a voice problem in the individual’s life has its peculiarities, advantages, and limitations. The many validation processes undertaken by several clinicians and researchers all over the world occurred in a quasi-steady fashion. Nonetheless, minimum adaptations were needed, and not a single item had to be withdrawn owing to lack of cultural representation. Recently, an Indian study has proposed a self-assessment protocol to be used in India (Konnai et al., 2010). This tool considers some prominent aspects of the environment and culture, such as noise and dust pollution, lack of acoustic amplification, lifestyle (spicy foods, excessive consumption of coffee, tea, and carbonated soft drinks), the tropical climate, and excessive voice use. The Voice-DOP is the only culture-specific QOL assessment tool developed for individuals with voice disorders and was created for the Kannada-speaking population in India. There are 21 different languages and many dialects spoken in India, suggesting that assessment tools may have to be developed for different languages despite occurrence in the same country (Konnai et al., 2010).

Specific cultural examples appropriate to India have been highlighted in the literature. For example, a street merchant selling food in a public railway station has to increase his vocal intensity above the noise of the loud trains and the congested crowd, in the dusty environment for long hours. A full-time teacher is likely to teach an average of about 30 classes per week, the duration of each class being about 40 minutes (Prakash, 2008). Moreover, in India most women have no paid employment, so questions related to the need for changing jobs because of a voice problem or to risk earning less money because of vocal difficulties may not be not applicable to females. Undoubtedly, other countries also retain certain cultural situations that are not readily addressed by the VHI or any self-assessment tool.

Auditory perceptual assessment of voice

Perceptual assessment and tools

The SLP’s clinical tradition is to describe numerous vocal parameters related to vocal quality, such as type of voice, glottal attack, resonance, pitch, loudness, respiratory dynamics, and vocal registers. It is known that the type of voice assessment protocol has a direct relation to the vocal physiology and an indirect relation to the acoustic analysis. It is well known that poor breath control and pulmonary pathologies may contribute to dysphonia; thus, it is necessary to develop a good respiratory pattern and coordination when treating dysphonia. It is also known that resonance, pitch, and loudness are more likely the genesis of a voice problem, which produces a negative psychodynamic impact. However, voice endurance to continuous speech, a central and vital use of voice-related aspect particularly for professional voice users, has been clinically underevaluated. Recent studies have superficially understood the impact of either the intensive voice use or the use of voice in adverse environmental conditions. There is not a screening or evaluation test that can be used in the clinic to characterize such parameters that is a frequent complaint of the dysphonic patient. Except for singers and actors, who represent the vocal elite, a voice produced with effort and fatigue should be more carefully considered than vocal quality deviations such as hoarseness and breathiness.

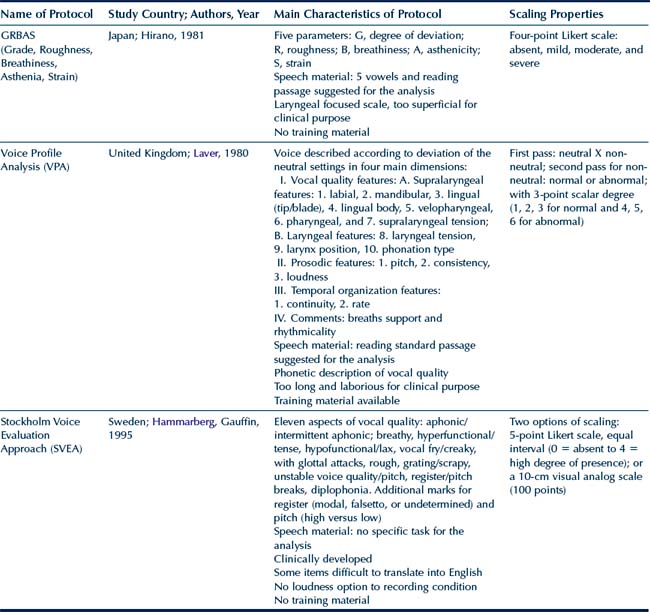

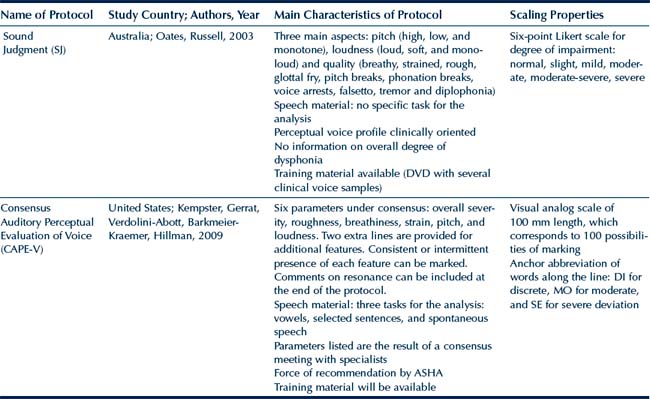

The worldwide basis of the clinical evaluation of the voice is still the auditory perceptual analysis that is performed by means of standardized protocols. Such an option allows information exchange between different centers. However, as the voice is multidimensional, its variables are numerous and they usually represent a specific center, country, and professional category profile. There are a wide range of perceptual protocols available, from which we can highlight: the Grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia, Strain (GRBAS) scale (Hirano, 1981), Voice Profile Analysis (VPA) (Laver, 1980), Stockholm Voice Evaluation Approach (SVEA) (Hammarberg & Gauffin, 1995), Sound Judgment (SJ) (Oates & Russell, 2003), and Consensus Auditory Perceptual Evaluation of Voice (CAPE-V) (Kempster et al., 2009). The CAPE-V was designed to analyze a minimum set of perceptual parameters that specialists agreed on, and also to have the possibility of including additional parameters in the analysis. The CAPE-V seems to offer an interesting solution that can be internationally employed; however, particular aspects of clinical needs must be considered. The main information in these five protocols is organized in Table 10-3.

The scale most widely used worldwide for perceptual auditory analysis is the GRBAS system, developed by the Japanese Committee of Phonatory Functions (Hirano, 1981). This system is composed by five parameters (G, overall deviation; R, degree of roughness; B, degree of breathiness; A, degree of asthenicity; and S, degree of strain) evaluated by a four-point Likert scale (0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe). Despite lack of clear definition of parameters and training material, this scale was disseminated all over the world. Some evident problems such as concentration on laryngeal contribution of the vocal quality and the fact that asthenicity and strain are the opposite of each other (therefore, one single parameter), the system appears in international publications in numerous countries. Recently, the CAPE-V protocol, proposed by the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association Special Interest Group 3 (Kepmster et al., 2009) has produced a change in the paradigm of vocal analysis. The strength of the consensus protocol relates to a clear definition of six vocal parameters (overall severity, roughness, breathiness, tension, pitch, and loudness) and the fact that it was designed after a task force project to understand trends in psychoacoustic analysis and after considering all available protocols (such as GRBAS, John Laver, and SVEA protocols). The protocol is short, is specific to voice, and offers the possibility of marking two extra parameters, if needed, plus the use of resonance. Moreover, this protocol is assessed by means of a visual analog scale with 100 points, which offers a more precise and detailed analysis.

The perceptual threshold for considering a voice normal is an interesting question for research. The worldwide singing expression is a live example of vocal variety, in which some cultures and musical styles clearly present certain preferences. For example, an opera singer must present a clear tone, with powerful projection, without any sign of roughness or breathiness. The rock singer’s production can be characterized by roughness and strain and still be acceptable. Another interesting example is the degree of breathiness welcomed in bossa nova singing, a traditional Brazilian music now embraced worldwide. The difficult task is to differentiate a personal and culturally accepted vocal style from the expression of a voice problem. A clear cutoff point for separating normal variation of vocal quality and abnormal vocal quality through auditory perceptual analysis was suggested by a Finnish group (Simberg et al., 2000) as 34 mm (on a total scale of 100 mm), using the G parameter from the GRBAS scale (overall deviation). This criterion was chosen based on a pilot study and tested on the analysis of 226 students. The results indicate that this specific point can be used as a screening criterion. A similar cutoff limit was defined by two Brazilian studies analyzing 211 voice samples (plus 10% of repetition for reliability analysis) from adults with and without vocal complaints (Yamasaki et al., 2010). Two evaluation analyses were performed, the first one by using a visual analog scale with 100 units and the second a four-point numerical scale (NS). The results provided a reference system for perceptual analysis, with four ranges: 0 to 35.5 units for normal variation of voice quality or mild dysphonia (0 to 1 NS); 35.6 to 50.5 units for mild to moderate deviation (1 to 2 NS); 50.6 to 90.5 units for moderate deviation (2 NS) and 90.6 to 100 for severe deviation (3 NS). The limit of 35.5 units, close to the Finnish study, is suggested as a screening level for perceptual auditory analysis. These results provide some evidence to support the claim that cultural and language backgrounds of the listeners would affect perception for some voice quality types. Thus, the cultural and language backgrounds of judges should be taken into consideration in clinical voice evaluation. Despite these discrepancies, the GRBAS scale may be an excellent tool for perceptual evaluation of voice quality by linguistically diverse groups.

The major change from the 1980s is to focus only on three vocal types that can be consistently identify regardless the culture (roughness, breathiness, and strain) instead of trying to detail any peculiarity of the voice type (Oates, 2009). Although clinicians also make judgments about other factors, such as strain in the client with spasmodic dysphonia and rate of speaking in the client with Parkinson’s disease, these parameters are usually less reliable when judged by groups of listeners or even the same listener repeatedly. Even though voice strain is a behavioral parameter that can be discretely rated in some cultures and languages, it may not be universally translated to others with the same degree of consistency and reliability as roughness and breathiness. Thus, roughness and breathiness, which have a more consistent construct across languages and cultures, are the most studied cross-cultural voice qualities (Yiu et al., 2008).

Linguistics, voice, and perception

Literature presents evidence that voice quality varies across languages and can even vary when an individual speaks two languages, as shown by Bruyninckx and associates (1994), when comparing voices produced by Catalan-Spanish bilinguals. The influence of language, particularly considering the way in which the phonetic properties may affect the manifestation of a voice problem, has not been studied properly. However, it seems plausible that certain vocal gestures regarding a specific linguistic code may introduce some adjustments that can interfere in the voice production of nonhealthy speakers. Lorch and Whurr (2003) reported that characterization of abductor spasmodic dysphonia in French speakers differs from that of English speakers in that the French did not show evidence of pitch breaks, only phonatory breaks, harshness, and breathiness. The frequency of occurrence of phonemes in French and English is different and may have been one of the factors regarding the expression of some of the vocal features.

Nguyen and colleagues (2009) studied female primary school teachers with muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) who use Vietnamese, a tonal language, to determine whether professional voice users of a tonal language presented with the same symptoms of speakers of a nontonal language. The results showed that MTD was associated with a larger number of vocal symptoms than previously reported. They found that the Vietnamese teachers did not have the same vocal symptoms as those reported in English-speaking teachers. For example, hard glottal attack, pitch breaks, unusual speech rate, and glottal fry were rare in the Vietnamese speakers. The authors highlight the potential contribution of linguistic-specific factors besides the teaching-related aspects to the presentation of this voice disorder.

Cross-linguistic variables, such as those reported by Lorch and Whurr (2003) and by Nguyen and colleagues (2009) and Nguyen and Kenny (2009a), may interfere in the diagnostic criteria of specific dysphonias and may interfere with the clinician’s ability to propose a clear diagnosis in speakers who use languages different from his or her native one. In the international arena, an understanding of speech-related effects on the voice provides the clinician with additional information when approaching the goals of treatment. Moreover, with the world population moving more and more toward large diverse metropolitan areas, there is more need to understand cultural variations. The current authors live in cities where the populations are higher than 5 million, and it is clear that cultural variations within the language play a major role in treatment planning and acceptance of the treatment outcome.

Few studies have investigated the cross-language perception of the voice in specific pathologies. To investigate this issue, Hartelius and coworkers (2003) compared the perceptual assessments of dysarthric samples by 10 Australian and 10 Swedish speakers with multiple sclerosis (MS) analyzed by 2 Australian and 2 Swedish clinically experienced judges. The consensus ratings from both judges were high for both the Australian and the Swedish speakers. They concluded that perceptual assessments of speech characteristics in individuals with MS are informative and can be achieved with high interjudge reliability irrespective of the judge’s knowledge of the speaker’s language. Thus, the universality of the voice parameters contributed to the perception of the disorder, regardless the language spoken.

Because voice quality is the expression of behavioral and cultural characteristics, different linguistic backgrounds may affect the evaluation of certain voice parameters. Few studies have explored these questions: Yamaguchi and associates (2003) studied the way in which Japanese and American clinicians (both SLPs and MDs) rated 35 Japanese voice samples using the GRBAS scale. There was no significant difference between the Japanese and American listeners in the use of the grade, roughness, and breathiness (G, R, B) scales. However, the asthenicity (A) and strain (S) scales, which reflect a more behavioral continuum, were judged differently between the two groups of listeners. The same vowel samples were judged by 74 Brazilian listeners (Behlau et al., 2001), and once again asthenicity and strain were judged differently from the Japanese listeners. The G factor achieved highest intercultural agreement, followed by roughness and breathiness. Thus, asthenicity and strain may be considered as discrete by the Japanese listeners but not by the American or Brazilian listeners.

Speakers identify voices from their own culture more accurately than voices from other cultures. Doty (1998) and Anders and associates (1988), in separate studies, demonstrated that accuracy in perceptual judgments was higher when judges identified speakers from their own country than speakers from other countries. In the Anders study, American listeners rated German symphonic voices with less severe dysphonias compared with German and Finnish listeners. The authors suggested that the lack of familiarity with the German language may have produced a more conservative evaluation.

The cultural and language backgrounds of judges interfere in the assessment of the vocal quality, even when using controlled synthesized signals and when listeners are from two different cultural and language backgrounds (Yiu and coworkers found significant differences between Australian and Hong Kong SLPs) when judging synthesized samples of various voice qualities (Yiu et al., 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree