OBJECTIVES

Define intimate partner violence (IPV), childhood exposure to IPV, and the epidemiology of IPV globally and in the United States.

Describe the health effects of IPV.

Describe risk factors for perpetration and victimization of IPV.

Review recommended screening, assessment, and intervention practices to address IPV in the health-care setting.

Jasmine grew up in an underserved urban neighborhood in the United States. Her father was an alcoholic who frequently assaulted her mother. When Jasmine was 14, her mother committed suicide, leaving Jasmine homeless. She has had a series of abusive boyfriends who have beaten and sexually assaulted her. She began using heroin a few years ago.

Amina grew up in a small village in Tanzania. Her father routinely beat her mother and insisted that Ahadi get married at age 16 to an older man with many other wives who offered to pay for Ahadi. Ahadi knows that when one of his other wives requested that he use a condom, he beat her so badly that she almost died. Ahadi is now pregnant with her third child.

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global epidemic and human rights issue. It has marked harmful effects on the safety, health, and overall well-being of those victimized, their families, and communities. The term intimate partner violence describes physical violence, sexual violence, threats of physical or sexual violence, and psychological abuse by a current or former intimate partner. IPV may occur throughout the lifespan, from adolescence to old age. While IPV is related to child abuse as children who are exposed to parental or guardian IPV are often also the victims of direct maltreatment (Table 35-1) and may become both victims and perpetrators in adulthood, discussion of child abuse and elder abuse are beyond the scope of this chapter.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| IPV | “[a] pattern of assaultive and coercive behaviors that may include inflicted physical injury, psychological abuse, sexual assault, progressive social isolation, stalking, deprivation, intimidation and threats. These behaviors are perpetrated by someone who is, was, or wishes to be involved in an intimate or dating relationship with an adult or adolescent, and are aimed at establishing control by one partner over the other”a |

| Child exposure to IPV | “…a wide range of experiences for children whose caregivers are being abused physically, sexually, or emotionally by an intimate partner. This term includes the child who observes a parent (or guardian) being harmed, threatened, or murdered, who overhears these behaviors… or who is exposed to the short- or long-term physical or emotional aftermath of a caregiver’s abuse without hearing or seeing a specific aggressive act…”a |

| Child maltreatment (abuse) | “An act or failure to act by a parent, caretaker, or other person as defined under State law which results in physical abuse, neglect, medical neglect, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm to a child”b |

For many victims, the health-care setting is the only safe point of contact outside of the abusive relationship and presents an ideal opportunity to identify and address IPV. Health-care providers who effectively screen for and address IPV can be the difference between life and death for victims of IPV and their families. This chapter describes IPV and provides an overview of how to address IPV in the health-care settings serving vulnerable populations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND HEALTH EFFECTS

The overall burden of IPV on girls and women is of epidemic proportions. An estimated 30% of women worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence perpetrated by their intimate partner.1 In the United States, more than one in three women (35.6%) have experienced physical violence, rape, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetimes, and 18.3% of all women have been raped in their lifetimes. Ninety percent of all rapes are committed by an intimate partner or an acquaintance.2 Globally, more than 38% of all female homicides (and 6.3% of male homicides) are committed by an intimate partner.3 In the United States in 2008, around 45% of female and 5% of male homicides were committed by an intimate partner.4

In medical settings, the prevalence of IPV is higher, likely due to the physical and mental health sequelae of IPV that prompt IPV victims to seek care. A study of adult patients seeking primary care at an urban public hospital revealed that 15% of women reported abuse within the last year, and 51% reported abuse in their lifetime.5 In the United States, IPV costs a staggering $8.3 billion annually due to $5.8 billion in medical costs for injuries and health sequelae and $2.5 billion in lost productivity.6

Most victims of IPV are women and women are far more likely than men to be injured when victimized by an intimate partner. Nevertheless, there is increasing recognition of IPV with male victims.2,7 Lesbian and gay people have rates of IPV victimization equal to or higher than heterosexual people,8 but rates for people who identify as bisexual are significantly higher.2 The prevalence of IPV among transgender people is not well studied but likely to be higher than in gender-conforming people.9

In adolescents and adults, IPV victimization results in poor mental and physical health, and sometimes life-long disability. IPV is also associated with a higher prevalence of chronic diseases including arthritis, asthma, stroke, heart attack, heart disease, hyperlipidemia, chronic pain, and high-risk behaviors such as tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, and high-risk sexual behaviors.10 In addition, IPV victimization correlates with mental health problems including posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, suicidality, eating disorders, and substance use.11 Globally, suicide rates are significantly elevated in women victims of IPV.12

As demonstrated by the histories of Jasmine and Amina, victims of IPV often have little control over their own sexual and reproductive health. Their partners are often non-monogamous, refuse to use condoms, sabotage birth control methods, and coerce them into unwanted pregnancies or abortions.13,14 Such reproductive coercion often results in an increased prevalence of unwanted pregnancy, abortion, HIV, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and gynecological problems.11 In parts of the world with high HIV prevalence, IPV has emerged as an important risk factor for HIV transmission.15 In addition, IPV is associated with poor birth outcomes such as fetal low birth weight, preterm births, and miscarriages.16 Furthermore, young women forced into early and abusive marriages are at extremely high risk of adverse maternal outcomes such as preeclampsia. Male IPV victims who have sex with men are also at increased risk for forced unprotected anal intercourse, as well as higher rates of depression, HIV, and substance abuse.17

It is estimated that almost 9 million children are exposed to parental or guardian IPV each year in the United States alone.18 Children may witness physical, sexual, and emotional violence; be caught in the “crossfire” of violent acts; or suffer direct child abuse. More than 50% of children who are exposed to IPV are also directly abused.19 Children exposed to IPV have multiple mental health, physical health, and behavioral problems including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, chronic somatic complaints, learning problems, increased aggression, fearfulness, and developmental problems.20,21 Adverse childhood experiences, such as being abused or witnessing parental violence, are increasingly being recognized as key determinants of health that have an impact on biological processes and brain development. Adverse childhood experiences often result in risky adult behaviors (e.g., smoking cigarettes, using drugs, having a higher number of sexual partners) and adulthood chronic diseases22 (see Chapter 36.)

There is an emerging body of literature examining perpetration of IPV. More than 40% of men attending urban clinics in a US city reported perpetrating physical and sexual IPV in the past year.23 Male perpetrators of IPV often have increased rates of childhood exposure to IPV and histories of child abuse.24 Recognizing and addressing this cycle of violence is essential to prevent children who are exposed to violence from growing into adults who perpetrate IPV. Moreover, men who perpetrate IPV are at risk for other poor health outcomes: they have high-risk sexual behaviors and a higher risk of being HIV positive, as well as have high rates of injury, psychiatric disease, substance use, irritable bowel syndrome, and insomnia.24

FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

Jasmine’s current partner, Carl, grew up in a family in which his father was an alcoholic who severely beat his mother, Carl, and Carl’s siblings. Carl never completed high school. He has been abusive to each of his girlfriends. Carl has been incarcerated twice for “domestic violence” and has never held a job for more than a few months.

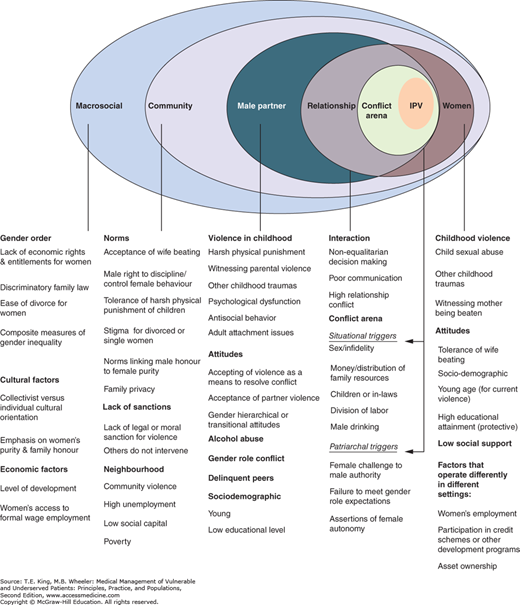

An “ecological model” has been developed to conceptualize individual, relationship, community, and macrosocial factors that support the development and persistence of IPV (Figure 35-1).25 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains lists of these evidence-based factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of IPV such as employment and educational status and substance use (Table 35-2). An understanding of these multilevel factors can help identify various opportunities for prevention.

Figure 35-1.

Revised conceptual framework for partner violence. Factors are color coded to communicate the strength of the evidence base linking that particular factor to the experience of partner violence. Factors colored blue have the strongest evidence base, green have medium evidence, and pink have the weakest or fewest number of studies supporting their role in partner violence. Factors in the far right-hand column (relating to the woman) have been consistently shown across studies and settings to increase a women’s risk of victimization. The remaining columns represent factors that have been shown to increase the likelihood of men’s perpetrating partner violence. Many related to the male partner show up repeatedly in multivariate analysis of cross-sectional surveys from low- and middle-income countries. Longitudinal cohort and intervention studies reinforce this evidence in many instances. Significantly, however, many of these more sophisticated studies come exclusively from high-income settings. (From Heise L. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. STRIVE, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, 2011:7.)

Individual risk factors

|

Relationship factors

|

Community factors

|

Societal factors

|

Many IPV victims and perpetrators lack these factors, and many men and women with these factors do not necessarily experience IPV. Violent relationships are “passed on” from one generation to the next as witnessing IPV or being abused by parents are associated with victimization and perpetration of IPV as an adult.26

ADDRESSING INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN THE HEALTH-CARE SETTING

Trevor is a 25-year-old man who presents for primary care complaining of daily headaches. Trevor’s male partner is very concerned about Trevor and accompanies him into the exam room. The provider allows Trevor’s partner to join the visit, takes a detailed history of Trevor’s headaches, and schedules a brain MRI. When Trevor returns, he sees a covering provider who separates Trevor from his partner and inquires about IPV. She learns that Trevor’s headaches began after his partner started abusing him physically and sexually.

Multiple professional medical associations in the United States now recommend routine universal screening for IPV victimization based upon its high prevalence, myriad adverse health effects, and infrequent identification when not done routinely.27,28,29 Routine screening for IPV is recommended by Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations for all hospitalized women,30 all women of childbearing age by the United States Preventive Services Taskforce,31 and is covered as an essential health service by all insurance companies under the Affordable Care Act.32 Additionally, the vast majority of patients state that they would like their health-care providers to ask them about IPV and that merely disclosing IPV privately to a trusted provider who responds compassionately is highly therapeutic.33 Routine screening and identification of IPV in health-care settings is beneficial and offers a crucial opportunity to support victims and break repetitive cycles of violence.

Unfortunately, most recommendations address IPV victimization in women only, leaving out gay male patients like Trevor, transgender male patients, and gay and heterosexual male patients, including boys, who present with indicators of abuse. Yet, there are guidelines about how to screen for and address IPV victimization in women and men including LGBTQ patients.9,28,34 We recommend adopting a universal screening approach for all girls and all women and those boys and men in high-risk populations.

In addition, people who perpetrate IPV are regularly seen in health-care settings but are rarely screened for IPV perpetration. Ultimately, in order to prevent IPV victimization, addressing perpetration is necessary. There is expert guidance on addressing IPV perpetration with men,34 but scant research in this area.24,35,36

Amalia is a Spanish-speaking, undocumented woman whose husband David first started criticizing her during her pregnancy. Since then, he has hit Amalia on numerous occasions. David has threatened to have Amalia deported if she reveals the abuse. When Amalia takes her daughter, Elena, to the pediatrician, he sees Amalia’s exhausted appearance, and says, “You look so tired and upset. I’m worried about you. Has David ever hit you or hurt you in any way?” Amalia says, “I’m afraid that he will hurt me if he finds out I’m talking to you.”

Reporting requirements for IPV and child abuse vary widely; therefore, clinicians need to learn about them for their specific locality, state, or country. The goal of screening is not to force disclosure of IPV but, rather, to express concern for a patient’s safety, respect for the patient’s autonomy, and offer help as needed. Through the development of compassionate, trusting relationships, the health-care team and community advocates can help reduce the patient’s isolation and increase the patient’s sense of empowerment. With proper training, various members of the health-care team can inquire about IPV. To ensure patient safety, professionally trained medical interpreters (rather than family members or friends) should be used to screen for and respond to IPV. The patient should be alone and in a private location when asked about IPV.

Detailed guidelines and validated tools for screening exist.21,28 (See https://secure3.convio.net/fvpf/site/Ecommerce/236886779?VIEW_PRODUCT=true&product_id=1861&store_id=1241; https://secure3.convio.net/fvpf/site/Ecommerce/1501428096?VIEW_PRODUCT=true&product_id=1811&store_id=1241.)37,38 Ideally, screening for IPV occurs within the context of a patient-centered conversation that is made relevant to the patient’s health. In general, direct questions (including questions about emotional abuse and reproductive coercion) increase identification of IPV, whereas vague questions about safety rarely elicit disclosures of IPV (Box 35-1). Introductory phrases can facilitate clinician and patient comfort with screening: “Because violence in relationships is so common, I ask all my patients about it. Has your partner ever hit, hurt or threatened you?”

Box 35-1. Tools to Screen and Assist with Intimate Partner Violence

| Mnemonics HITSa tool: How often does your partner

|

Direct questions

|

Questions about emotional abuse

|