3 Intracerebral Hemorrhage Stanley Tuhrim Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) occurs in 12 to 31 per 100,000 people each year in the United States, accounting for 10% of all strokes.1 It has the highest mortality rate among stroke types (30 to 50%).2 The rate is expected to double in the next 50 years because of the increasing age of the population and the increased use of antithrombotic therapy. ICH is more common among men, the elderly, African Americans and Japanese, and people with low low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Hypertension is the major modifiable risk factor for ICH. Excessive alcohol consumption also markedly increases risk. Although clinical trials of specific interventions have been disappointing, rapid recognition and comprehensive management are essential to limiting mortality and long-term morbidity. Due to a variety of factors, estimates of in-hospital mortality have been halved over the past three decades. Note blood pressure (BP), evidence of head or other trauma.

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

| Location | Exam Findings |

| Subcortical white matter or putamen | Aphasia (left) or neglect (right) Contralateral motor or sensory deficits Conjugate gaze palsy, hemianopia |

| Thalamus | Aphasia (left) or neglect (right) Contralateral sensory ± motor deficits (from involvement of adjacent internal capsule) Wrong-way gaze (away from lesion), downward eye deviation Sectoranopia Small reactive pupils |

| Brainstem | Coma Quadriparesis Locked-in syndrome at the level of the pontine tegmentum (conscious and quadriparetic with preserved vertical eye movements) Horizontal gaze paresis (pontine hemorrhage) Ocular bobbing (pontine hemorrhage) Pinpoint pupils (pontine hemorrhage) Fixed midposition pupils, hippus (midbrain hemorrhage) Nystagmus Hyperthermia Abnormal breathing patterns |

| Cerebellum | Limb or truncal ataxia Nystagmus Skew deviation Brainstem signs from mass effect Signs of hydrocephalus and elevated ICP from compression of the fourth ventricle |

Abbreviation: ICP, intracranial pressure.

Differential Diagnosis

Ischemic stroke, metabolic coma, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, and nonconvulsive status epilepticus can all mimic ICH, though the diagnosis is readily determined with CT. Below is a differential diagnosis of ICH by etiology.

- Chronic hypertension. Common locations include basal ganglia (40 to 50%), lobar regions (20 to 50%), thalamus (10 to 15%), pons (5 to 12%), cerebellum (5 to 10%) (dentate nucleus is common for hypertensive ICH and vermis for coagulopathic ICH), and other brainstem sites (1 to 5%).

- Related to rupture of Charcot-Bouchard microaneurysms, lipohyalinosis, and fibrinoid necrosis affecting penetrating arteries

- Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) occurs in one-third of cases; commonly related to a thalamic or caudate ICH that ruptures into the ventricle

- Clinical history of hypertension, especially uncontrolled, or eclampsia

- Assess for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) on electrocardiogram (ECG) and hypertensive changes in retina or kidney.

- Related to rupture of Charcot-Bouchard microaneurysms, lipohyalinosis, and fibrinoid necrosis affecting penetrating arteries

- Amyloid angiopathy

- Age >60 years old

- ß-amyloid deposition in small- and medium-sized arteries

- Apo E2 and E4 alleles are more common with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related ICH.

- Lobar location, leukoariosis, multiple posteriorly located gradient echo signals on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- History of Alzheimer’s dementia

- Multicompartmental bleeds (ICH + subdural hemorrhage SDH or ICH + SAH)

- Recurrent ICH (recurrence rate up to 10% annually)

- Age >60 years old

- Coagulopathy

- Clinical history, including warfarin use, hemophilia, or other clotting abnormality, liver or renal disease (uremic platelets)

- Warfarin is a risk factor for ICH expansion, with expansion continuing longer than in patients not taking warfarin, and is associated with worse outcomes.

- Multifocal bleeds more common

- Cerebellar vermis location common

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Deep or superficial location

- Flow voids on imaging studies

- History of seizures or headaches

- Absence of clinical history of hypertension or coagulopathy

- Younger age

- Initial bleeding rate is 2 to 4% per year; recurrent bleeding rate is 6 to 18% per year.3–5

- Lifetime risk of hemorrhage is 105 minus patient’s age (in years).6

- Cavernous angioma

- Deep or superficial location

- History of headaches or seizures

- Frequently multiple “popcorn” gradient echo lesions on MRI with varying ages of blood

- Angiographically occult (may see associated developmental venous anomaly)

- Annual bleeding rate is 0.25 to 1.1% in the anterior circulation with a rebleeding rate of 4.5% per year. The annual bleeding rate for posterior fossa cavernous malformations is 2 to 3% with a 17 to 21% rebleeding rate.7

- Genetics—KRIT-1 (CCM-1), CCM-2, PDCD-10 mutations

- Cocaine, methamphetamine, or sympathomimetic drug use

- Dural sinus thrombosis with hemorrhage

- Seen in hypercoagulable states, dehydration, Crohn’s disease

- Common cause of postpartum period ICH

- Look for signs of elevated ICP; check opening pressure with lumbar puncture.

- Requires full-dose anticoagulation, even with hemorrhage present8

- Neoplasm

- Most common primary tumors with hemorrhage—glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), oligodendroglioma, pituitary adenoma

- Most common metastatic tumors with hemorrhage—lung, melanoma, thyroid, renal, choriocarcinoma

- Vasculopathy

- Rupture of small- or medium-sized arteries produces hemorrhage.

- Typically preceded by weeks to months of headache, cognitive decline, psychiatric symptoms, and multiple strokes

- May be associated with systemic illness (polyarteritis nodosa [PAN]; Wegener’s granulomatosis; Churg-Strauss syndrome; cryoglobulinemia; systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]; rheumatoid arthritis; Sjögren’s syndrome; tuberculosis [TB]; bacterial, fungal, or viral vasculitis; hepatitis; herpes; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]; postpartum; Lyme disease; sarcoidosis; Behçet’s disease; syphilis; drug-induced [cocaine and methamphetamines] vasculopathy; sickle cell disease or carcinomatous vasculopathy) or limited to the central nervous system (Call-Fleming syndrome, primary CNS granulomatosis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, MoyaMoya disease)

- Ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion

- Underlying vascular territory lesion with petechial hemorrhage. Hemorrhagic infarction is typically heterogeneous and conforms to an arterial distribution. Primary ICH is homogeneous and does not necessarily conform to an arterial territory.

- More common with embolic strokes with reperfusion

- Occurs in 6% of patients after intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)9

- Trauma

- External evidence of trauma

- Multifocal hemorrhages

- Associated SDH, SAH, contusion, skull fracture

- Clinical history, including warfarin use, hemophilia, or other clotting abnormality, liver or renal disease (uremic platelets)

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

- Coagulopathy-induced ICH because rapid factor correction can limit ICH expansion

- Surgical lesions or associated IVH requiring ventricular drainage

Diagnostic Evaluation

- Imaging studies

- CT: Assess volume by A*B*C/2 method,10 assess location (deep, superficial, cerebellar, IVH), presence of hydrocephalus, midline shift (measured from septum pellucidum), or evidence of trauma (contusion, SAH); assess for AVM or underlying mass. CT scan remains the initial study of choice to distinguish infarction from ICH. Thirty-eight percent of patients will have a 33% increase in ICH size within 3 hours (two-thirds of cases will have expansion within 1 hour).11 Increase in ICH volume is associated with early neurologic deterioration.12 CT angiography may be useful for identifying an aneurysm or vascular malformation.

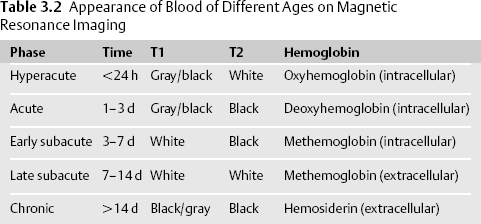

- MRI is at least as sensitive for diagnosing ICH but more difficult to interpret because the appearance of ICH changes as blood products age.13 MRI (with contrast) is superior to CT for detecting underlying structural lesions (tumors, cavernous malformations, ischemic stroke), delineating edema, and identifying venous thrombosis (MR venography). MRI may not be feasible due to impaired consciousness, hemodynamic instability, pacemaker, or agitation. MRI with gadolinium should be considered in patients with a history of cancer or risk factors for cancer, no history of hypertension, or suspicious ICH location (i.e., lobar at the gray-white junction) (Table 3.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

- CT: Assess volume by A*B*C/2 method,10 assess location (deep, superficial, cerebellar, IVH), presence of hydrocephalus, midline shift (measured from septum pellucidum), or evidence of trauma (contusion, SAH); assess for AVM or underlying mass. CT scan remains the initial study of choice to distinguish infarction from ICH. Thirty-eight percent of patients will have a 33% increase in ICH size within 3 hours (two-thirds of cases will have expansion within 1 hour).11 Increase in ICH volume is associated with early neurologic deterioration.12 CT angiography may be useful for identifying an aneurysm or vascular malformation.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree