No

Significant hemorrhage

Other complications

Subsequent microsurgical excision

Subsequent adjunctive therapies

High grades gliomas

VL

1

1

1

3rd V

4

1

3

Low grades gliomas

VL

2

2

3rd V

5

Diabetes insipidusa

1

3

4th V

1

1

Germinomas

VL

–

3rd V

6

Dissemination

6

Pineocytoma

VL

–

3rd V

7

1

Parinaud

7

Malignant pineal tumors

VL

–

3rd V

4

Parinaud

1

3

Metastases

VL

1

1

1

3rd V

4

4

Lymphomas

VL

2

2

3rd V

2

1

2

Craniopharyngiomas

VL

–

3rd V

6

3rd nerve palsy

5

3

PNETs

VL

2

1

2

2

3rd V

–

Meningiomas

VL

1

1

3rd V

1

1

Sarcoidosis

VL

–

3rd V

1

1

Not conclusive

VL

–

3rd V

1

1

Total

51

6 (11.7 %)

5 (9.8 %)

20 (39.2 %)

32 (62.7 %)

Endoscopic Aspiration of Cystic Brain Tumors

Several brain tumors may present cystic aspect. Cystic components are relatively typical for craniopahryngiomas, hemangioblastomas, and pilocytic astrocytomas, but may be present also in malignant gliomas, metastases and so on. Attempts at cyst aspiration belong to the history of neurosurgery, but simple aspiration represented just palliation and remained not popular till recently when modern adjunctive therapies became available. In particular, the advent of frameless stereotaxis, endoscopy and radiosurgery offers new tools to face with selected cases of cystic brain tumor. In fact, now the cyst aspiration has the purpose to decrease the cyst volume and improve the patient’s suitability for radiosurgery, by transforming the remaining cystic mass is an adequately small solid mass (Park et al. 2011). The cyst aspiration with or without subsequent radiosurgical treatment have been reported for various types of cerebral tumors (Hadjipanayis et al. 2002; Miki et al. 2008; Pan et al. 1998; Reda et al. 2002) but this treatment seems more properly suitable for craniopharyngiomas (Barajas et al. 2002; Joki et al. 2002; Nicolato et al. 2004; Park et al. 2011). In these particular tumors, the cystic component often represents even 80–90 % of the total mass (Nicolato et al. 2004). It is well known that the best treatment option for craniopharyngioma is radical microsurgical removal. However, in many cases, radical excision may be problematic and dangerous owing to the very tight adhesions to the optic pathways, the hypothalamus and the pituitary stalk. In fact, visual deterioration, endocrine disturbance, and hypothalamic dysfunction are not unusual following radical surgery. Furthermore, the rate of 5-year recurrences following radical resection has been reported in the order of 50 % (Puget et al. 2007). An alternative treatment strategy may be the subtotal resection followed by radiation therapy or radiosurgery on the residual tumor, integrated in selected cases by endoscopic cyst aspiration, cyst marsupialisation. A permanent catheter with an Ommaya reservoir may be also placed to repeat cyst aspiration and/or to deliver intracystic chemotherapy or radioactive drugs. A further less invasive management may consist of direct neuroendoscopy combined with stereotactic radiosurgery used as primary treatment in a multimodal strategy (Barajas et al. 2002; Joki et al. 2002; Reda et al. 2002). Of course, less invasive is the management, lower is the rate of complications but higher is the rate of recurrences and shorter is the disease-free interval (Park et al. 2011). However, since their mini-invasivity, endoscopic procedures may be repeated without major problems (Fig. 19.1).

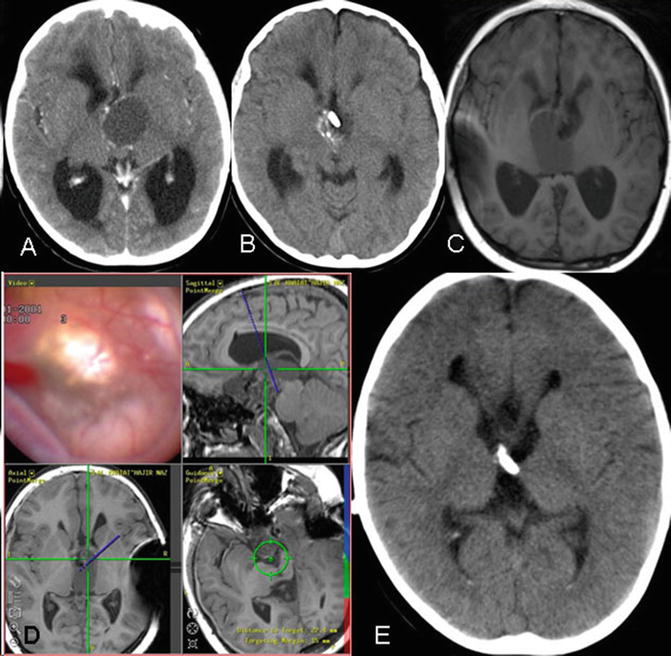

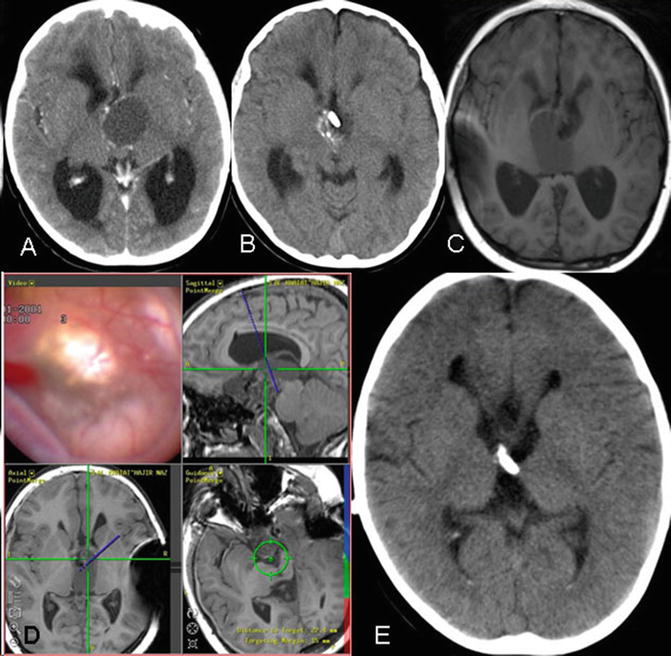

Fig. 19.1

Cystic craniopharyngioma recurring 2 years after subtotal microsurgical excision. (a) CT-scan showing a cystic mass inside the 3rd ventricle. (b) Postoperative CT-scan following transventricular endoscopic access with cyst aspiration and placement of an intracystic catheter with an Ommaya reservoir. Note the typical calcification inside the 3rd ventricle close to the catheter tip. (c) RMN obtained 1 year later showing a new cyst completely filling the 3rd ventricle. (d) Snapshot of the neuronavigator screen showing the endoscopic view of the cyst wall at level of the Monro Foramen; the planned trajectory is also shown: the tumor cyst is being to be fenestrated on the superior dome towards the lateral ventricles and on the inferior floor toward the brainstem cisterns. A sort of ETV is being created through the cyst in order to maintain it washed away. Three months after surgery, the patient will undergo gamma-knife. (e) Follow-up CT scan obtained 2 years later: no cyst is evident: note the new catheter coming from the Ommaya reservoir cruising through the right Monro Foramen towards the cisterns

In our clinical practice, the first treatment option for craniopharyngioma usually consists of an attempt at gross total removal. In this regard, endoscopic assisted microsurgery may be very useful; sometimes a transventricular endoscopic approach may provide the view from above, while the tumor is resected through the pterional or the inter-emispheric/subfrontal approaches. Depending on tumor size and local anatomical conditions, the planned gross total removal often has to be converted in subtotal excision. The tumor parts which are more tightly joined to the hypothalamus or the cranial nerves are usually deliberately left in place. We think, the present availability of powerful alternative therapies should prevent the neurosurgeon from feeling forced to pursue radical solutions at any cost. Therefore, postsurgery, the solid tumor rests are treated by gamma-knife, while the cystic residual lesions are endoscopically managed. Endoscopic treatment usually consists of an image-guided procedure with trans-ventricular trajectories that are selected to approach the cysts from above. We think intracystic bleomicine has no role owing to the high risk of toxicity in case of intraventricular diffusion. Accordingly, we try to create the widest possible communications between the ventricles and the cysts and between the cysts and the subarachnoid spaces. Suprasellar cysts are fenestrated both on the superior and inferior walls so that the ventricles can communicate with the subarachnoid space through the cyst itself. Therefore, a sort 3rd ventriculostomy is created through the cyst (Fig. 19.1). This would maintain washed the cyst in the hope that the risk of cyst recurrence could be decreased or at least delayed. In our experience there was no case of chemical ventriculitis due to the diffusion of the cyst content. Theoretically, cyst aspiration and fenestration could be also obtained by stereotaxis (Park et al. 2011). However, the wall of these cysts is often calcified and thick, and the endoscope has the undoubted advantage that the wall may be handled under direct visual control and using the various endoscopic instruments. Usually, a ventricular catheter is placed through the fenestrations as a sort of stent, and anchored to a subcutaneous Ommaya reservoir. This may be useful for subsequent cyst aspiration.

At our Institution, during the last 15 years, a total of 11 patients with recurrent or residual craniopharyngioma underwent endoscopic cyst fenestration and subsequent radiotherapy (6 patients before 2008) or radiosurgery (the last 5 patients). Multiple repeated endoscopic procedures were needed in 8 of 11 patients owing to cyst recurrence. Two patients required subsequent adjunctive microsurgical removal. Endoscopy associated with conventional radiotherapy represented just a palliation and had scarce efficacy on the global disease control. Conversely, the preliminary experience with endoscopy plus radiosurgery seems more satisfactory but the follow-up period is too short to draw any definitive conclusion.

Recently, a small number of large cystic metastatic lesions, which were initially deemed not amenable for radiosurgery, have been treated by endoscopic cyst aspiration and subsequent gamma-knife on the shrunk rest. These results seem encouraging.

Endoscopic Resection of Brain Tumors

Since the beginning of neuroendoscopy, endoscopic tumor resection was one of the main ambitions. Indeed, cases of endoscopically removed brain tumors remain sporadic (Sood et al. 2011; Souweidane et al. 2006). Bi-portal approaches, single large port using multiple instruments by two hands, dedicated ultrasonic aspirators, laser, and myriad tumor resection devices have been developed, but, to date, the only tumor which is currently endoscopically resected is the colloid cyst. This is a benign tumor, which accounts for less than 1 % of brain tumors and typically originates from the roof of the 3rd ventricle being closely associated with the velum interpositum and the choroid plexus near the foramen of Monro (Boogaarts et al. 2011; Levine et al. 2007). It may be occasionally found and may even remain asymptomatic, but obliteration of the Monro foramina and acute hydrocephalus are possible with severe clinical manifestations and even sudden death. While there are few doubts about the surgical treatment of symptomatic cases, indications of occasionally found cysts are sometimes debated (Boogaarts et al. 2011; Greenlee et al. 2008; Levine et al. 2007). Surgical treatment ranges from simple ventricular drainage to radical cyst resection. During the past decades, microsurgical excision through the transcortical/transventricular or the transcallosal approaches became the treatment of choice. However, despite morbidity and mortality progressively declined, their rates remained not negligible (Boogaarts et al. 2011; Mathiesen et al. 1997). Postoperative epilepsy, venous infarction, and damage to the fornices were not uncommon. Therefore, neuroendoscopy progressively gained wide acceptance for the treatment of colloid cysts (Boogaarts et al. 2011; Greenlee et al. 2008; Hellwig et al. 2003; Levine et al. 2007; Longatti et al. 2006a). The mini-invasivity of endoscopy would warrant lower complication rates above all for what concerns postoperative seizures and fornices damage (Boogaarts et al. 2011; Greenlee et al. 2008). Indeed, memory disturbances are not uncommon even following endoscopy, but they would be more often transitory than following microsurgery (Greenlee et al. 2008). The better neurological results would be counterbalanced by higher rates of cyst recurrence due to the endoscopic difficulty to achieve complete cyst wall removal (Levine et al. 2007). However, the question about the real importance of complete cyst removal still remains unsettled (Levine et al. 2007). Very long disease-free periods have been reported following partial excision while cyst recurrence is possible even following apparently total cyst removal (Boogaarts et al. 2011). Of course, in these cases, owing to the peculiar pathology of the colloid cysts, it is reasonable to think that the removal is just apparently total, and cyst recurs originating from small remnants which are seen neither during surgery nor on postoperative MRI. The MRI features have been analyzed to predict the cyst behaviour: hyperintensity on T2-weighted images would indicate higher probability of cyst growing, while hypointensity on the same images would predict difficulty in endoscopic cyst aspiration and proper removal (Boogaarts et al. 2011). Anyway, over the last few years, the rates of endoscopic total or nearly total removal improved from 65 % to 90 % (Boogaarts et al. 2011; Hellwig et al. 2003; Longatti et al. 2006a), but probably less radicality remains justified by lower complication rates. Moreover, in case of cyst recurrence, a new endoscopic treatment is not only possible but it may result even easier (Boogaarts et al. 2011).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree