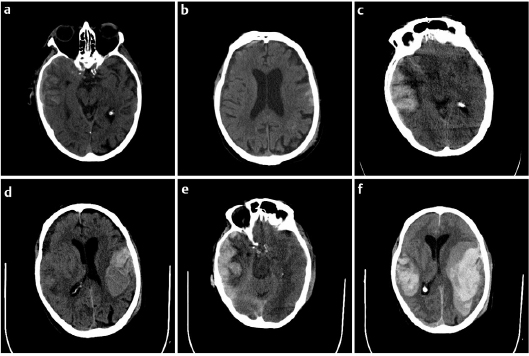

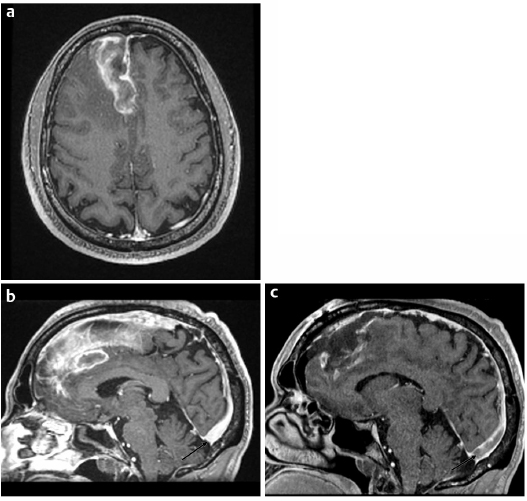

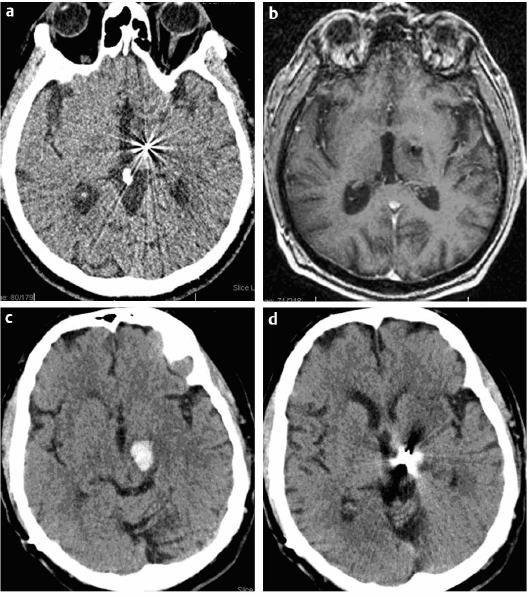

24 Management of patients undergoing cranial surgery involves all aspects of coagulation and bleeding, both positive and negative. This chapter presents specific cases to highlight these issues. An 83-year-old man suffered a ground-level fall at home. There was no loss of consciousness. Upon arrival in the emergency room, he complained of nausea, but his Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 15. He had been started on dabigatran (oral direct thrombin inhibitor) 1 month prior to admission for new-onset atrial fibrillation. His admission laboratories demonstrated a hematocrit of 41 and normal platelet count. His prothrombin time (PT)/international normalized ratio (INR) was 17.2 seconds/1.4, and his partial thromboplastin time (PTT) was 43 seconds. His thrombin time was > 150 seconds (normal 14.7–19.5). His initial computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 24.1a,b) demonstrated relatively minor subarachnoid hemorrhage and contusions. He was admitted to the Neurocritical Care Unit, and Keppra was started for seizure prophylaxis. Approximately 2 hours later, he became aphasic and a repeat CT was performed (Fig. 24.1c,d), which demonstrated interval increase in intracerebral hemorrhage bilaterally. He was administered a weight-based dose of factor VII. He became increasingly somnolent, and a follow-up CT was performed 4 hours following admission (Fig. 24.1e,f), which demonstrated significant evolution of intracerebral hemorrhage. At the family’s wishes, no further treatment was offered and he expired from his intracerebral hemorrhage. Dabigatran is a synthetic, oral direct competitive thrombin inhibitor; 80% of the drug is excreted renally. Serum half-life is 12 to 17 hours, and the drug does not require routine monitoring with INR. There is no direct antidote; hemodialysis can remove 60% of the circulating drug. The administration of factor VIIa may help (it did not alter the outcome in this unfortunate case), but fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and vitamin K administration are not effective. Although the option of dialysis was discussed in this case, the ability to perform rapid dialysis, even in a trauma center, is problematic. In a patient taking dabigatran, the PT/INR is usually not affected.1 Similarly, the PTT is not elevated. The thrombin time (TT) and ecarin clotting time (ECT) are sensitive to the drug, and a normal TT and ECT exclude the presence of significant dabigatran levels.1 A 53-year-old man presented with a 6-week history of progressively worsening headaches. His GCS was 15 and he had a normal neurologic examination except for papilledema. A CT head and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan were performed, which identified a heterogeneously enhancing right parasagittal frontal lobe lesion with significant surrounding edema (Fig. 24.2a). The presumptive diagnosis was a primary brain tumor, most likely glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The patient’s admission laboratories were normal. He was started on Decadron, resulting in quick symptom relief. Surgery was performed to resect the lesion, which was uneventful. However, the lesion was more consistent with an old hematoma, and a thrombosed cortical vein was identified extending from the area of the lesion to the sagittal sinus. Frozen section pathological examination and final pathology demonstrated no tumor, only evidence of hemorrhage and necrosis. There was no evidence of thrombus on the initial MRI scan. Fig. 24.2b shows the region of the posterior sagittal sinus, which is free of thrombosis. The postoperative MRI scan done 24 hours later identified thrombus in the superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 24.2c). The patient was started on low-dose unfractionated heparin immediately postoperative. Full-dose intravenous (IV) heparin was started 24 hours after his craniotomy. Heparin was then converted to warfarin starting on the 5th postoperative day. He suffered no complications from the anticoagulation, which was continued for 6 months. Follow-up MRI demonstrated complete recanalization of his venous sinuses. After discontinuing warfarin, the patient underwent testing for risk factors for hypercoagulability, all of which were negative. Fig. 24.2a–c (a) Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan demonstrates heterogeneously enhancing right para-sagittal frontal lobe lesion with significant surrounding edema and (b) showing the region of the posterior sagittal sinus, which is free of thrombosis (arrow). (c) Postoperative MRI scan done 24 hours later identified thrombus in the superior sagittal sinus (arrow). This patient’s presentation was somewhat atypical but was totally secondary to venous thrombosis and hemorrhage. The intraoperative findings and postoperative MRI established the diagnosis. There was no definite evidence of sagittal sinus thrombus on the preoperative MRI. The appropriate treatment for cranial venous thrombosis is anticoagulation.2,3 He remained clinically stable in the early postoperative period, and there was no evidence of any deep venous involvement. He was started on subcutaneous heparin immediately, to provide some effect on thrombus progression. Full-dose IV heparin therapy was withheld until 24 hours postoperatively, in recognition that this represented a risk for thrombus progression, but also trying to balance the risk associated with full anticoagulation in a patient who has just had a craniotomy. A 74-year-old man with Parkinson disease who was increasingly impaired by motor fluctuations underwent an uncomplicated placement of a left subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrode for control of his symptoms. Following surgery his symptoms dramatically improved and he was able to reduce his Parkinson medications, and a postoperative CT scan (Fig. 24.3a) demonstrated good electrode placement. Fig. 24.3a–d (a) Immediate postoperative CT scan demonstrating left deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrode in the subthalamic nucleus (STN). (b) MRI (T1-weighted) done 4 months postoperatively demonstrates subacute hemorrhage along the DBS electrode. (c,d) CT scan done 1 week after MRI demonstrating significant interval hemorrhage around the tip of the electrode.

Intraoperative Cranial-Specific Patient/Case Examples

Case 1: Catastrophic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Associated with Dabigatran

Discussion

Case 2: Hemorrhage Associated with Sagittal Sinus Thrombosis

Discussion

Case 3: Intracerebral Hemorrhage Associated with Edoxaban

Intraoperative Cranial-Specific Patient/Case Examples

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree