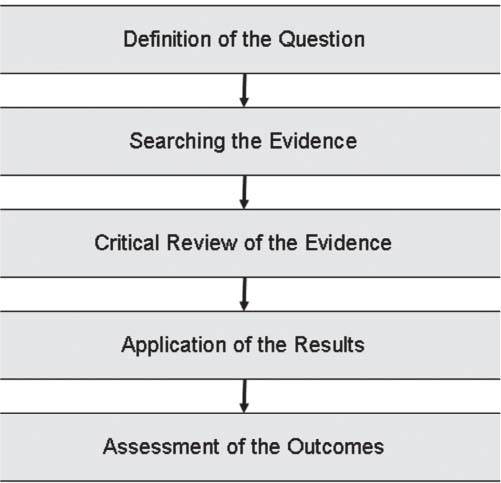

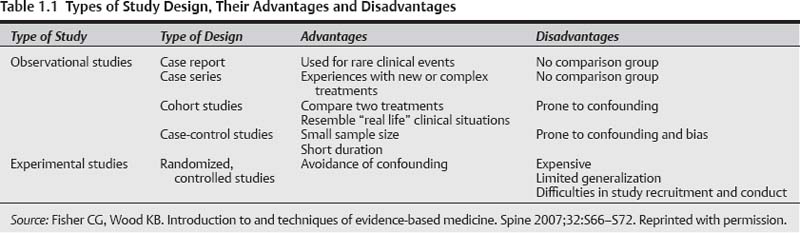

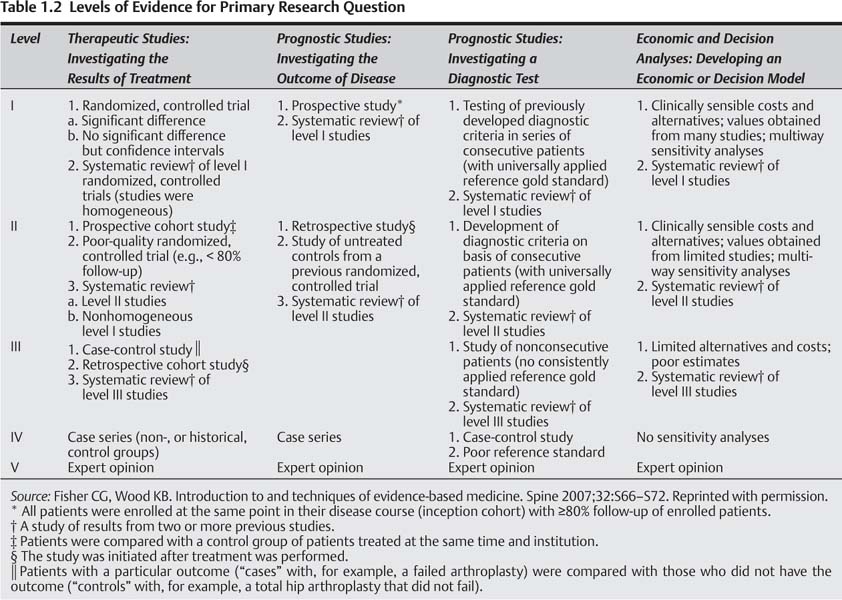

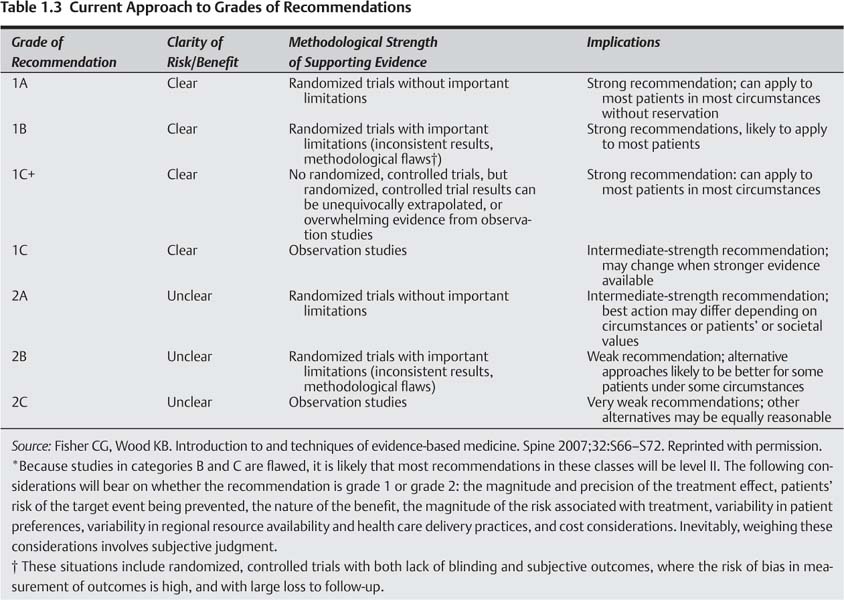

1 During the past decade there has been an ongoing initiative to utilize sound scientific evidence in medical decision making in an attempt to improve patient care. This concept is referred to as evidence-based medicine (EBM), and it has been advocated by physicians, epidemiologists, insurance payers, the media, and patients. It was selected as one of the most important ideas that made a difference in our lives by the New York Times Magazine in 2001.1 It has been applied to nearly every subspecialty in medicine, the topic of focus issues in peer-reviewed journals, and discussed in consensus statements of medical societies.2–5 Although the concept of EBM is widely discussed, there remains an overall lack of understanding among many investigators and clinicians. To effectively apply this concept to the practice of patient care a better understanding of the process is necessary. There are five steps involved in EBM (Fig. 1.1). First, the question has to be defined. Although this may appear to be a straightforward task, it can be one of the most problematic issues related to EBM. To effectively apply EBM, the question has to be well defined in terms of the patient population, confounding factors, specific treatments or interventions, and measured outcomes. The question being asked determines the most appropriate type of study to obtain the answer. Not every study is most appropriately addressed with a randomized, controlled trial (RCT). Fisher and Wood have summarized the common types of studies with their advantages and disadvantages (Table 1.1).6 The second component of EBM is searching the evidence. This task has been simplified by the ease of use of multiple electronic search engines. These allow for a comprehensive search of specific terms of multiple databases and English and foreign language journals. The third step is to perform a critical appraisal of the literature. This step involves categorizing the current literature based on study type, level of evidence, and applying grades of recommendation. There are various methods used to categorize levels of evidence. One of the most commonly utilized is that adopted by the American edition of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, which is outlined in Table 1.2.7,8 As detailed in Table 1.2, studies are first categorized according to therapeutic, prognostic, diagnostic, or economic studies. Once this is done, the study is assigned a level based on the type of study performed. Study designs that eliminate the most bias and control for the most confounding factors receive a higher ranking. RCTs are given the highest ranking, and case reports and expert opinions are given the lowest rankings. Grades of recommendation are then applied according to the criteria set forth by Guyatt et al.9 As with applying levels of evidence, the use of grades of recommendation attempts to provide a reproducible method to assign a score to the study based on the strength of the article and a clear risk:benefit ratio for the described treatment. As described in Table 1.3, the better the grade of recommendation, the more clear risk:benefit ratio and stronger recommendation to accept the proposed treatment described in the article. Fig. 1.1 Diagram of the five components of evidence-based medicine. The fourth component is to apply the results of the literature to patient care. This step takes the information gained in the previous steps and allows the clinician to develop appropriate treatment recommendations supported by the literature. In spine surgery, there are a limited number of RCTs and highly graded studies. As a result it can be more difficult for clinicians to base their practice on clinical data. Unfortunately, in fields with limited availability of highly graded studies, clinicians often base their decisions on anecdotal evidence alone. We would propose that even in the absence of highly graded studies, the best available evidence should be identified and considered in clinical decision making. We refer to this as best evidence medicine. Even in the absence of high-level scientific studies, there is often a collection of lower-grade studies that can provide some guidance for clinical decision making.

Introduction to Best Evidence Medicine

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree