Introduction to Mood Disorders

John R. Geddes

Mood and disorders of mood

The concept of mood is difficult to define. In psychiatry, it has come to mean a pervasive emotional tone varying along an axis from happiness to sadness—and perhaps anxiety. The boundaries between normal and abnormal mood are equally difficult to define. Nonetheless, there is usually no doubt about the most extreme manifestations of low mood, depression, or elevated mood, mania.

Early history

Descriptions of variations in mood which go beyond normal limits and are associated with functional impairment are present in the oldest writings of mankind.(1) The ancient Greeks identified that mood disorders were diseases of the body, rather than the effects of supernatural spirits and identified the link between elevation of mood and states of despondency or depression. The Hippocratics also identified that mental disorders were located in the brain. This insight was lost for 2000 years under the influence of Galen’s humoral theory which held that melancholia was due to an excess of black bile and mania due to an excess of yellow bile. During this period, attempts to put forward empirical theories in both Western and Eastern civilizations often fell foul of increasingly dominant religious dogma.

Development of modern psychiatric nosology

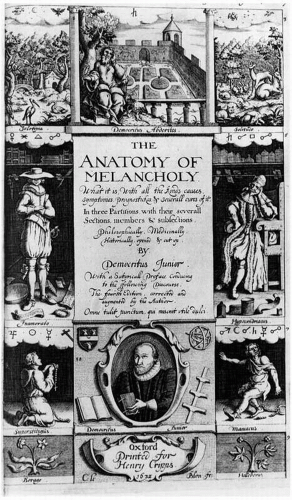

In Europe, during the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, reason and empiricism once again emerged. In Anatomy of Melancholy, published in 1632, Richard Burton provides a comprehensive review of previous writings on mood disorder.(2) Burton, who writes with the penetrating insight of someone with extensive personal experience of mood disorder, clearly makes the link between mood elevation and enhanced creativity, cycling with periods of low mood, when all pleasure is lost:

When I go musing all alone

Thinking of divers things fore-known.

When I build castles in the air,

Void of sorrow and void of fear,

Pleasing myself with phantasms sweet,

Methinks the time runs very fleet.

All my joys to this are folly,

Naught so sweet as melancholy.

When I lie waking all alone,

Recounting what I have ill done,

My thoughts on me then tyrannise,

Fear and sorrow me surprise,

Whether I tarry still or go,

Methinks the time moves very slow.

All my griefs to this are jolly,

Naught so mad as melancholy.

(extract from The Author’s Abstract of Melancholy, Anatomy of Melancholy)

Burton’s work is an erudite and comprehensive review of the work on mood disorders until the early seventeenth century, although of course not systematic in the modern sense. Following Burton, Thomas Willis (1621-1675), Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy at Oxford University, perhaps better known for his description of the eponymous circle of Willis, is now recognized as one of the first to (re)localize psychiatric disorders within specific body organs, primarily the brain, rather than due to the circulation of bodily humours. In Cerebri anatomi (1664) Willis writes(3):

Melancholy is a complicated distemper of the brain and heart. For as melancholick people talk idly, it proceeds from the vice or fault of the brain and the inordination of the animal spirits dwelling in it, but as they become very sad and fearful, this is deservedly attributed to the passion of the heart. But we cannot here yield to what some physicians affirm, that melancholy doth arise from a melancholick humour. Melancholy being a long time protracted, passes oftentimes into stupidity, or foolishness, and sometimes into madness.

This identification of the physical brain as the location of the involved pathological processes initiated the modernist project of the scientific study of serious mood disorder, using contemporarily available scientific methods to generate insights into diagnosis, aetiology, course, and treatment. The first steps in this project were diagnosis and classification. Modern psychiatric diagnostic systems can be traced to post-Enlightenment Europe—in particular, France. The development of the mental hospital system throughout Europe provided the populations of patients for the early psychiatrists to study, as they created and refined diagnostic systems. In 1854, Esquirol described la folie circulaire which remains a recognizably modern description of bipolar disorder.(4) Despite this, the prevalent view throughout the nineteenth century was that manic and depressive states were separate entities. At the turn of the twentieth century, Kraepelin distinguished dementia praecox from manic-depressive insanity(5) Kraepelin emphasized the episodic course of the latter, the relatively benign prognosis and the family history of mood disorder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree