Learning Disabilities

Elena L. Grigorenko

Fundamentally, the concept of learning disabilities (LDs) has to do with society’s capacity “to monitor (and recruit) children for unexplained school failure in a way that was not possible before the LD category was reified and passed into law in 1969 (1)”. The LD category replaced a variety of loose definitional references to previously used qualifiers such as slow learner, backward children (2) and minimal brain dysfunction (3).

In terms of its realization in the context of current practices, the LD label typically assumes the presence of the following process. Under normal circumstances, LDs are not diagnosable prior to the child’s engagement with schooling and the opportunity to master key academic competencies. While in school, a child is assumed to be assigned tasks that are grade appropriate. These tasks assume some degree of variability in children’s performance; these theoretical ranges constrain the definitions

of acceptable and worrisome variability in performance. It is when the child’s performance consistently falls out of the acceptable range in one or more academic subjects that the child becomes the focus of intense observation and documentation and is referred for evaluation to appropriate professionals (educational psychologists, neuropsychologists, and clinicians such as pediatricians, clinical psychologists, or psychiatrists). An important qualifier here is that such observation, documentation, and evaluation are considered only for children whose performance is below that expected based on their general capacity to learn; thus, the concept of “unexpected” school failure is central to the definition of LD. When reports on the child’s performance in the classroom, testing results, and clinical evaluations are compiled, the child and his or her family are referred to a special education committee, which determines eligibility for individualized special education services. If eligibility is established, an individualized education program (IEP) is created. The IEP refers to a specific diagnostic label carried by the child and cites a proper category of public laws that guarantees services for an individual with such a diagnosis.

of acceptable and worrisome variability in performance. It is when the child’s performance consistently falls out of the acceptable range in one or more academic subjects that the child becomes the focus of intense observation and documentation and is referred for evaluation to appropriate professionals (educational psychologists, neuropsychologists, and clinicians such as pediatricians, clinical psychologists, or psychiatrists). An important qualifier here is that such observation, documentation, and evaluation are considered only for children whose performance is below that expected based on their general capacity to learn; thus, the concept of “unexpected” school failure is central to the definition of LD. When reports on the child’s performance in the classroom, testing results, and clinical evaluations are compiled, the child and his or her family are referred to a special education committee, which determines eligibility for individualized special education services. If eligibility is established, an individualized education program (IEP) is created. The IEP refers to a specific diagnostic label carried by the child and cites a proper category of public laws that guarantees services for an individual with such a diagnosis.

Definition

The definition that currently drives federal regulations was produced by the National Advisory Committee on Handicapped Children in 1968 and subsequently adopted by the U.S. Office of Education in 1977 (4). According to this definition,

Specific learning disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations. The term includes such conditions as perceptual handicaps, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. The term does not include children who have learning problems which are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor handicaps, of mental retardation, or emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage (5).

DSM-IV does not use the term learning disabilities, but makes a reference to the term learning disorders (6). According to DSM-IV, a learning disorder can be diagnosed “…when the individual’s achievement on individually administered, standardized tests in reading, mathematics, or written expression is substantially below that expected for age, schooling, and level of intelligence.” Of interest here is that this is one of the very few categories of DSM-IV where a reference is made explicitly to psychological tests, although, as stated, DSM-IV does not provide specific guidelines as to what “substantially below” means. Thus, DSM-IV implicitly refers to evidence-based practices (3) as they exist in the field. The problem, of course, is that there are multiple interpretations of these best practices (see discussion following). Yet, assuming there are consistent and coherent guidelines in place for establishing the diagnosis of LD, DSM-IV classifies types of LDs by referencing the primary academic areas of difficulty. The classification includes three specific categories and a residual diagnosis: Reading Disorder, Mathematics Disorder, Disorder of Written Expression, and Learning Disorder NOS. A common practice in the field is to view a diagnosis of a learning disorder as established by DSM-IV as an equivalent to “specific learning disability,” which qualifies a child for special services under federal regulations (7).

History

The introduction of the concept of LD is typically credited to Samuel Kirk (then a professor of special education at the University of Illinois), who, while presenting at a parent meeting in Chicago on April 6, 1963, proposed the term learning disabled to refer to “children who have disorders in development of language, speech, reading, and associated communication skills” (ref, http://www.audiblox2000.com/book2.htm). The category was well received by parents and promoted shortly thereafter by an established parent advocacy group known as the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities. Prior to the formal introduction of this concept, the literature had accumulated numerous descriptions of isolated cases and group analyses of children with specific deficits in isolated domains of academic performance (e.g., reading and math) whose profiles were later reinterpreted as those of individuals with specific LDs (e.g., specific reading and math disabilities). It is those examples in the literature and the experiences of many distressed parents who could not find adequate educational support for their struggling children that, in part, resulted in the creation of the field of LDs as a social reality and professional practice (8). Subsequent accumulation of research evidence and experiential pressure led to the formulation of legislation protecting the rights of children with LDs.

Congress enacted the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94–142) in 1975 to support states and educational institutions in protecting the rights of, meeting the individual needs of, and improving the results of schooling for infants, toddlers, children, and youth with disabilities, and their families. This landmark law is currently enacted as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, Public Law 105-17), as amended in 2004. The importance of this law is difficult to overstate given that, prior to its enactment, in 1970, U.S. schools provided education to only one in five children with disabilities (9). By 2003–2004, the number of children served under IDEA aged 3–21 was 6,633,902 (http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d04/tables/dt04_054.asp). Specific learning disabilities make up 50% of all special education students served under IDEA.

In its 2004 amendment, IDEA1 recognized 13 categories under which a child can be identified as having a disability: autism; deaf–blindness; deafness; emotional disturbance; hearing impairment; mental retardation; multiple disabilities; orthopedic impairment; other health impairment; specific learning disability; speech or language impairment; traumatic brain injury; and visual impairment, including blindness. It is of note that LDs as described above in IDEA are referred to as “specific learning disabilities” to emphasize the difference between children with SLD and those with general learning difficulties characteristic of other IDEA categories (e.g., autism and mental retardation). The consensus in the field is that children with LDs possess average to above-average levels of intelligence across many domains of functioning, but demonstrate specific deficits within a narrow range of academic skills. Finally, as stated above, exclusionary factors have been central to diagnoses of LDs since the authoritative definition of LD was introduced in 1977. As per these exclusionary criteria, a child cannot be diagnosed with an LD unless other factors such as other disorders or lack of exposure to high-quality age-, language-, and culture-appropriate educational environments have been ruled out. It is the desire to rule out the exclusionary factor of lack of exposure to high-quality environments that prompted the introduction of the concept of

Response to Treatment Intervention [RTI2 (10)] in the 2004 amendment of IDEA (see more detail on RTI3 below).

Response to Treatment Intervention [RTI2 (10)] in the 2004 amendment of IDEA (see more detail on RTI3 below).

Epidemiology

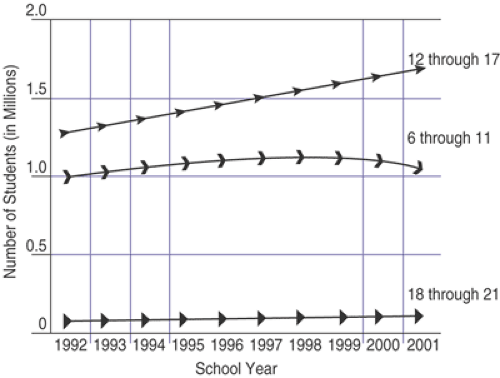

There are two main sources for obtaining estimates for prevalence rates of LDs. The first and most obvious one is linked to the number of children served under this category of IDEA. Figure 5.1.3.1 provides relevant data. When these data are mapped on the total number of school-aged children in the United States, although the number fluctuates from year to year, the average estimates of prevalence rates for LDs are around 5% to 6% of the total school-age population. To illustrate, in 2003, 2.72 million children were identified as having LDs. This represents a 150% to 200% increase in the number of students with LDs aged 6–17 compared with that number in 1975.

Yet it is important to note that prevalence rates very substantially from district to district and from state to state. For example, in 2004, under the specific learning disabilities category, in Kentucky, 1.8% of all students aged 6–21 received special education services compared with 5.9% in Iowa. Thus, based on these numbers, the prevalence rates of LDs in Iowa are about 3.3 times as high as in Kentucky, two states not very far apart geographically! This observation stresses the mosaic-like situation of LD diagnosis— there is no unified approach to these diagnoses across different local education agencies in the United States.

When IDEA-related prevalence rates are considered, LDs are observed more frequently in boys than in girls (64.5% vs. 33.5% for boys and girls aged 6–17, respectively) and more frequently in underrepresented minority groups than in Asian Americans or whites (the risk ratios4 are 1.5, 0.4, 1.3, 1.1, 0.9 for American Indian, Asian American, African American, Hispanic American, and white students, respectively).

The second source for these rates is research studies. Per results from these studies, it is assumed that although up to 10% to 12% of school-age children show specific deficits in selected academic domains, high-quality classroom instruction and supplemental intensive small-group activities can reduce this number to ∼6% of children. It is assumed that these 6% will meet strict criteria for LDs and will need special education intervention.

It is important to note that most of the research in the field of LDs is currently conducted with reading and, correspondingly, specific reading disability (SRD). There is little established evidence that reliably points to prevalence rates of disorders of math and writing.

To illustrate, according to the results of current research on early reading acquisition, 2% to 6% of children do not show expected progress even in the context of the highest quality evidence-based reading instructions. Based on U.S. national data, the risk for reading problems as defined through failure to reach age- and grade-adequate milestones ranges from 20% to 80%. Specifically, data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress 2005 shows that 36% of fourth graders do not possess the adequate reading skills required for completion of grade-appropriate educational tasks (http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pdf/main2005/2006451. pdf). However, it is clear that far from all of these children have SRD. The majority of these children underachieve, mostly likely, because of inadequate educational experiences and causes other than SRD.

Some changes in the 2004 version of IDEA were invoked directly because of concerns regarding the overidentification of students as learning disabled. The category of LDs has often been the largest single category of children served under IDEA (for latest relevant statistics, see https://www.ideadata.org/PartBReport.asp). The reality of everyday practices in school districts was such that most diagnoses prior to the 2004 reauthorization were based on so-called aptitude–achievement discrepancy criteria, which required a severe discrepancy between IQ and achievement scores (e.g., 2 standard deviations, 2 years of age equivalence), although IDEA had never specifically required a discrepancy formula (11). Correspondingly, it has been argued that these discrepancy-based approaches are flawed (12) and might have led to overidentification. In light of this hypothesis, IDEA 2004 emphasizes that there is no explicit IQ–achievement discrepancy requirement for diagnosis of LDs. As a possible alternative approach for identification and diagnosis, IDEA 2004 states that local educational agencies may use a child’s RTI in lieu of the classification processes (13). A local educational agency (e.g., a school) may choose to administer to the child in question an evidence-based intervention program and, depending on the child’s response to this program, determine his or her eligibility for special education services under IDEA.

Specifically, the statutory language of the IDEA 2004 (Public Law 108–446) states:

(6) Specific Learning Disabilities.

(A) In general.

Notwithstanding section 607(b), when determining whether a child has a specific learning disability as defined in section 602, a local

educational agency shall not be required to take into consideration whether a child has a severe discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability in oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skill, reading comprehension, mathematical calculation, or mathematical reasoning.

educational agency shall not be required to take into consideration whether a child has a severe discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability in oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skill, reading comprehension, mathematical calculation, or mathematical reasoning.

(B) Additional authority.

In determining whether a child has a specific learning disability, a local educational agency may use a process that determines if the child responds to scientific, research-based intervention as a part of the evaluation procedures described in paragraphs (2) and (3). [§614(b)(6)]

As a consequence of this language, although aptitude–achievement discrepancy has been and continues to remain the common, although not required, practice for local educational agencies, there is a new “entry point” for RTI. Needless to say, these changes are of great theoretical and practical importance. The tradition and system of specific LD identification in the United States is fluid now, and rather few specific recommendations exist to help local educational agencies smoothly transition into the implementation of IDEA 2004.

Etiology

There is a consensus in the field that LDs arise from intrinsic factors and have neurobiological bases, specifically atypicalities of brain maturation and function. There is a substantial body of literature convincingly supporting this consensus and pointing to genetic factors as major etiological factors of LDs. The working assumption in the field is that these genetic factors affect the development, maturation, and functional structure of the brain, which in turn, influences cognitive processes associated with LDs. Yet, the field is acutely aware that a number of external risk factors, such as poverty and lack of educational opportunities, affect patterns of brain development and function and, correspondingly, might worsen the prognosis for biological predisposition for LDs or act as a trigger in LD manifestation.

Although this model, in main strokes, appears to be relevant to all LDs, far more research on relevant genes and brain structure and function is available for children with SRD than for any other LDs. Thus, here illustrative findings are presented from SRD [for a more comprehensive review, see (14)].

Multiple methodological techniques (e.g., EEG, ERP, fMRI, MEG, PET, TMS,5 to name a few) have been used to elicit brain–reading relationships [for recent reviews, see (15,16,17)]. When data from multiple sources are combined, it appears that a developed, automatized skill of reading engages a wide, bilateral (but predominantly left-hemispheric) network of brain areas passing activation from occipitotemporal, through temporal (posterior), toward frontal (precentral and inferior frontal gyri) lobes. Clearly, the process of reading is multifaceted and involves evocation of orthographical, phonological, and semantic representations that, in turn, call for the activation of brain networks participating in visual, auditory, and conceptual processing. Correspondingly, it is expected that the areas of activation serve as anatomic substrates supporting all these types of representation and processing.

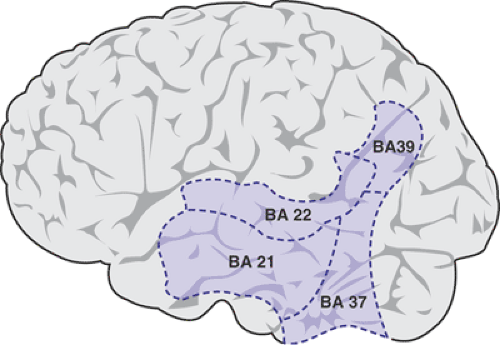

However, possibly somewhat surprisingly, per recent reviews, there appear to be only four areas of the brain of particular, specific interest with regard to reading (Figure 5.1.3.2). These areas are the fusiform gyrus (the occipitotemporal cortex in the ventral portion of Brodmann’s area 37, BA 37), the posterior portion of the middle temporal gyrus (roughly BA 21, but possibly more specifically, the ventral border with BA 37 and the dorsal border of the superior temporal sulcus), the angular gyrus (BA 39), and the posterior portion of the superior temporal gyrus (BA 22).

It is also important to note the developmental changes in patterns of brain functioning that occur with increased mastery of reading skill: progressive, behaviorally modulated development of left-hemispheric “versions” of these areas and progressive disengagement of right-hemispheric areas. In addition, there appears to be a shift of regional activation preferences: The frontal regions are used by fluent more than by beginning readers, and readers with difficulties activate the parietal and occipital regions more than the frontal regions.

In an attempt to understand the mechanism of the “deficient” pattern of brain activation while engaged in reading, researchers are looking for genes that might be responsible, at least partially, for these observed differences in functional brain patterns. This search is supported by a set of convergent lines of evidence [for reviews, see (18,19,20)]. First, SRD has been considered a familial disorder since the late nineteenth century. This consideration is grounded in years of research into the familiarity of SRD (similarity on the skill of reading among relatives of different degree), characterized by studies that have engaged multiple genetic methodologies, specifically twin (21,22,23), family (24,25,26) and sib-pair designs (27,28). Although each of these methodologies has its own resolution power with regard to explaining similarities among relatives by referring to genes and environments as sources of these similarities and obtaining corresponding estimates of relative contributions of genes and environments, all methodologies have produced data that unanimously point to genetic similarities as the main source of familiarity of SRD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree