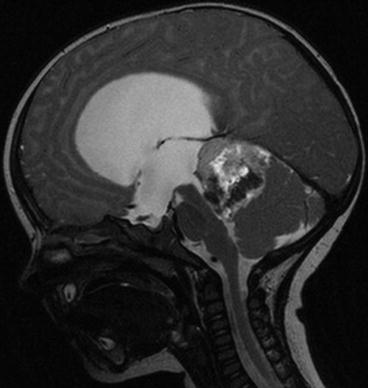

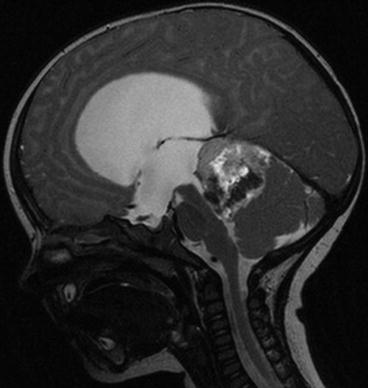

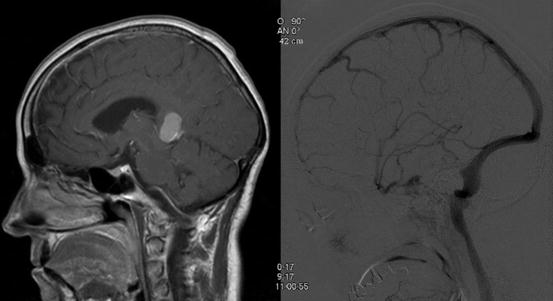

Fig. 1

Illustration of the median sagittal view of the brain (left). Same view in MRI, T1 + CM (right)

Although the pineal gland has a relatively redundant arterial supply by the A. lamina tecti and the A. choroidea posterior for surgical purposes, it is more important to consider the anatomy of the venous structures in this region, since these drain the vitally essential structures of diencephalon and mesencephalon. Hence, a venous lesion possibly leads to congestion and severe damage of aforesaid cerebral areas.

The internal cerebral veins, draining blood from pallidum, striatum and dorsal thalamic parts, form together with the basal veins of Rosenthal the internal cerebral vein of Galen. The confluence is located on top of the pineal gland. The vein of Galen also contains drainages from the occipital and upper cerebellar regions and flows into the straight sinus.

Although the localisation and anatomical characteristics of the pineal body were well known to ancient scientists such as Galen and Hippocrates, its function and relevance as a gland started to be investigated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century under “modern” scientific points of view [14]. The detailed hormonal function, in particular the production and secretion of melatonin, was described even much later in the 1950s by Lerner et al.

To date, there are several different aspects of the pineal function discussed. As a photosensitive organ with light depending secretion activity this gland is supposed to have an influence on circadian and circannual functions of human body such as sleep-wake rhythm and the release of gonadotropic pituitary hormones, which regulate the pubertal maturation processes.

Some more effects, e.g. on dendritogenesis [18], renal function [34] and immune function [10] as well as antioxidant activity, were also described lately. Finally, melatonin is also used in therapy of mental disorders, especially depression and it is supposed to have a positive impact on cancer therapy.

Clinical Aspects

The most common symptoms leading to the diagnosis of a lesion in this site, such as hydrocephalus and signs of a related ICP as well as visual disorders [12, 35, 57], are well explained by the anatomical location, since a lesion in the pineal region may occlude the Sylvian aqueduct or affect tectal and other mesencephalic structures. The latter rarely leads to paresis or paraesthesia. Also, seizures are not common; they may rather be related to a decompensated hydrocephalus than to the tumour location.

Regarding the physiological functions of the pineal gland, one may also expect hormonal disorders (e.g. precocious puberty) or a malfunction of the circadian rhythm (insomnia) other.

Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus itself is seen in the majority of the cases, often as the presenting sign. Konovalov describes in 58 % of cases a symptomatic hydrocephalus, Cho et al. [12] in about 60 % and Vaquero et al. [57] even in up to 100 % of their cases, which, however, were not all symptomatic. The acuity of the symptoms is mainly depending on the severity of the hydrocephalus and not on the tumour itself. Headaches are also frequently mentioned as a leading symptom in the literature, but there is no differentiation made between those related to raised ICP and/or hydrocephalus and non-specific headaches (Fig. 2).

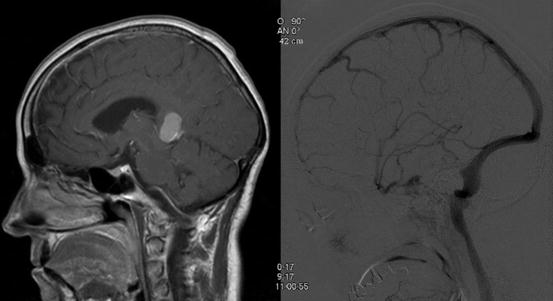

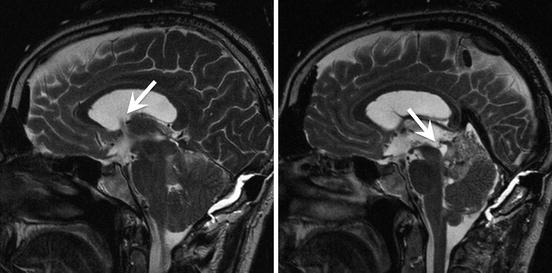

Fig. 2

Occlusive hydrocephalus caused by an ATRT of the pineal region in a 9-month-old male patient (MRI, T2, sagittal)

Ophthalmological Symptoms

Visual disorders in general terms are reported to be one of the most common symptoms in patients with pineal region tumours [3, 12, 35, 57]; nevertheless, most authors do not differentiate between the diverse ophthalmological symptoms explicitly. Although Parinaud’s syndrome (upward gaze palsy, accommodative paresis, convergence-retraction nystagmus) is a typical phenomenon observed in patients with lesions affecting the superior colliculi of tectum, we in fact observed in our series, that other complex and unspecific visual disorders are supposed to be at least just as common. Due to advances in surgical techniques visual or oculomotoric deficits, as a complication to surgical treatment (especially to open surgery), do not occur very often and once presenting, they are usually transient and totally reversible [6].

Circadian Rhythm

Not only the influence of the circadian rhythm on growth of malignancies [27] but also the interaction between cancer therapy and the sleep-wake pattern is subject of scientific interest time and again; fatigue is also a well-known phenomenon related to adjuvant therapy. But a disturbance of the circadian rhythm related to a pineal region tumour is not reported very often in the literature. Mandera et al. [39] describe “very high night levels of melatonin in patients with pineocytomas” but no details about its influence on sleep-wake modalities. Engel et al. [21] observed only in 1 out of 13 cases circadian rhythm disturbance which also occurred in a patient suffering from pineocytoma. Larger series even do not mention this subject [12, 35, 57]. Obviously this symptom is either occurring rarely in these cases or it also may be observed more often but mostly misunderstood as an unspecific side effect of the therapy or a paraneoplastic phenomenon of the neoplasia in general. In our series of 114 patients being operated on pineal region lesions, we observed only one person complaining from sleeping disorders initially, four more patients suffered from similar symptoms post-operatively. In all cases, the intake of melatonin (Circadin®) helped to relieve the complaints.

Endocrinology

Although the pineal body is a part of the neuroendocrine system, hormonal disorders occur only in few cases of patients with tumours in this area. In our series, there only were 2 patients out of 114 suffering from endocrinological symptoms.

Diabetes insipidus as a symptom in the context of a pineal region tumour was described more than 60 years ago [30]. Since then other symptoms, such as precocious puberty and panhypopituitarism, also were related to these lesions.

Some authors even postulate a correlation between entity (namely germ cell tumours) and the specific endocrinological deficiency: Vaquero et al. [57] report on precocious puberty (3 germinomas and 1 embryonal carcinoma), diabetes insipidus (4 germinomas and 1 glioblastoma) and panhypopituitarism (one germonima). The lack of large multicentric observations makes it difficult to draw reliable conclusions of these observations. Nevertheless in most of these cases, the initial symptoms disappear when the underlying disease is treated successfully.

Some germ cell tumours (GCT) characteristically secrete proteins or hormones, which can be detected in CSF and serum. The value of the laboratory results is subject to discussion (section “Serum and CSF markers”) where some typical patterns or tumour marker constellations can be defined related to specific tumours (Table 1).

Table 1

Possible tumour marker constellations in serum or CSF as described by Janss and Mapstone [32]

Tumour type | α-Fetoprotein (aFP) | Chorionic gonadotropin (ßHCG) | Placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) |

|---|---|---|---|

Germinoma | − | ± | + |

Teratoma | − | − | ± |

Malignant teratoma | ± | ± | ± |

Undifferentiated germ cell tumour | ± | ± | ± |

Choriocarcinoma | − | + | ± |

Endodermal sinus tumour | + | − | ± |

Embryonal cell tumour | + | + | ± |

Pineocytoma | − | − | − |

Pineoblastoma (PNET) | − | − | − |

Epidemiology

Tumours of the pineal region are rare lesions of different entities amounting about 1 % of intracranial tumours. The incidence of the subgroups varies regionally; tumours of germ cell origin—as a major subgroup—occur much more often in the Far East, especially in Japan than in Northern Europe or the United States (see also section “Germ cell tumours”). Other entities have a more evenly distributed incidence irrespective of the geographic conditions.

GCT and pineal parenchymal tumours (PPT) make up the major part of the entities, and male patients dominate in the cohorts as well as children and young adolescents. We counted in our series 114 patients with a mean age of 26 years operated on lesion of the pineal region, from which 57 % were of male gender. The histological distribution of the operated lesions is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3

Distribution of the diagnoses in our series (n = 114)

Neuro-oncological Aspects

Pineal region tumours (PRT) include multiple entities of different biological characteristics; therefore, the subgroups should be considered and evaluated separately in order to define more specific diagnostic and therapeutic pathways.

According to the origin of the tumour, the WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system currently distinguishes between following entities:

Germ cell tumours (GCT)

Germinoma

Embryonal carcinoma

Yolk-sac tumour

Choriocarcinoma

Teratoma

Mature

Immature

Teratoma with malignant transformation

Mixed germ cell tumours

Tumours of the pineal parenchyma (PPT)

Pineocytoma

Pineal parenchymal tumour of intermediate differentiation

Pineoblastoma

Papillary tumour of the pineal region

Tumours of supportive and adjacent structures

Astrocytoma

Meningioma

Non-neoplastic tumour-like conditions

Pineal cysts

Vascular malformations

Metastases

This classification is mainly histologically oriented. Taking clinical features of the GCT into account, some authors also group embryonal carcinomas, yolk-sac tumours (synonymous with endodermal sinus tumours), choriocarcinomas and immature teratomas as non-germinomatous germ cell tumours (NGGCT, [29]), which are treated in a similar way. Alternatively, some authors prefer to differentiate between secreting and non-secreting germ cell tumours. This definition is closer to the actual clinical approach (see also chapter “Minor and repetitive head injury”).

Diagnostics

Imaging

The progressive calcification of the pineal gland during life makes it visible in the CT scan at least in adults. Other details of any pathological lesion in this area are only insufficiently shown by this imaging modality. MRI without and with contrast is the modern and adequate method to perform a useful and informative preoperative imaging. It is of utmost relevance to have all three planes imaged and preferably even a sequence in which CSF flow can be assessed (see below) [44]. Parker and Waziri even consider a pre-operative full craniospinal MRI as necessary, since spinal CSF metastases occur sometimes in cases of pineal tumours, specially the malignancies and germ cell tumours. Multilocular lesions around the midline are suspected to be germinomas (Fig. 4). For some tumour entities, the demonstration of craniospinal or intracranial dissemination of the tumour is relevant for tumour staging and the allocation to stage specific adjuvant treatment protocols and selection of therapy regimens (Fig. 5).

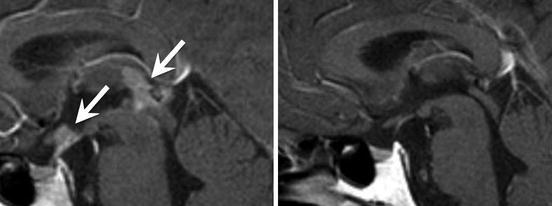

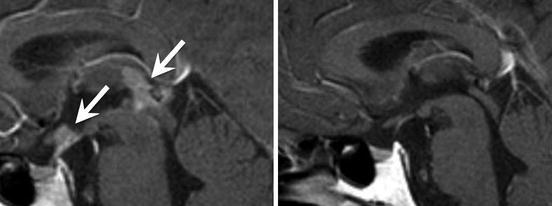

Fig. 4

Multilocular intracranial germinoma in a 21-year-old male before (left) and after (right) radiotherapy. The arrows show lesions in the perisellar and pineal region (MRI pictures courtesy of PD Dr. J. Flitsch)

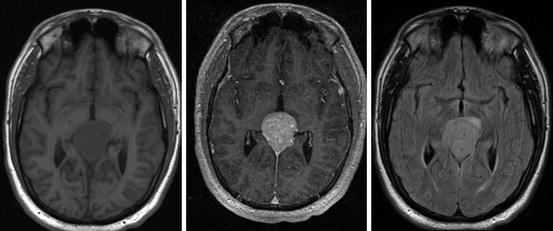

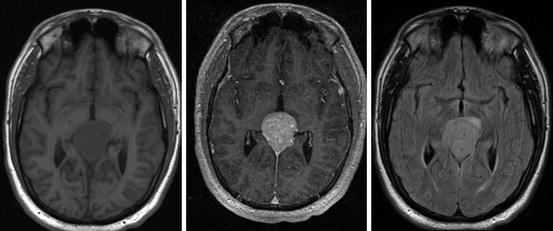

Fig. 5

A 16-year-old boy with a monolocular pineal region germinoma (from left: MRI T1, T1 + CM, TIRM)

Extensive imaging is relevant as it allows for the visualisation of the exact anatomical conditions around the tumour for surgical planning (tentorial angle, position of the quadrigeminal plate) and may reveal areas or infiltration, attachments and the vascular situation.

Specific vascular imaging by angiography is normally unnecessary, as arterial structures do not play an important role in surgical procedures or planning for parenchymal lesions of the pineal region. Vascular lesions like small AVMs (not part of this series) are of course different. An exception is lesions possibly involving the venous system at the tentorial notch where haemodynamics and collateralisation and position of the veins determine the approach and the options to transect venous structures (Fig. 6).

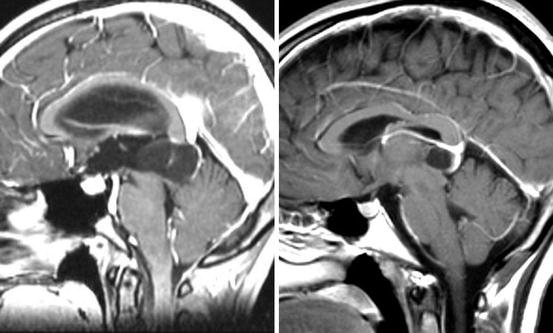

Fig. 6

MRI, sagittal, T1 + CM (left) of a 60-year-old woman with a pineal region meningioma compressing the inner cerebral veins from above, leading to anterograde flow in the internal veins as an expression of long-standing collateralisation as seen in the DSA (right). The vein of Galen does not seem to have any drainage into the straight sinus, allowing for dissection of the tentorial origin of the tumour. Because of the downward venous displacement, a midline parieto-occipital partially transtentorial approach is chosen here

Whatever modern MR imaging provides as information about the anatomical and local conditions prior to planning any procedure, none of the imaging modalities are currently able to substitute for histological evaluation and except for secreting or multilocular tumours with cerebrospinal fluid cytology no diagnosis can be made based on images alone (Fig. 7) [20].

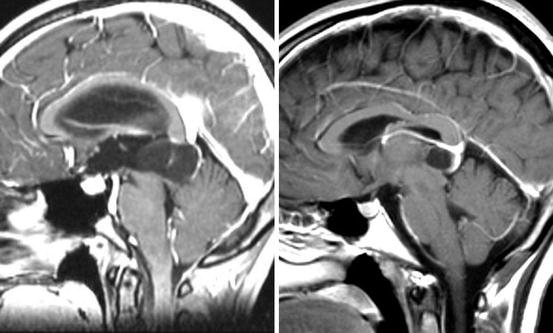

Fig. 7

MRI sagittal, T1 + CM of a 28-year-old woman with a pineal cyst (left) and T1 + CM of a 27-year-old woman with a pineocytoma (right). Radiologically one cannot distinguish reliably between one and the other. Both lesions present a cystic structure with minimal contrast medium enhancement in the margin area

CSF Flow Measurements

Modern MRI techniques, e.g. special T2 sequences, can illustrate CSF flow through turbulences caused by the flow void resulting from fluid turbulences (Fig. 8). This indeed can be helpful in order either to monitor the patency of the aqueduct in case of suspected obstruction or to check the functional efficiency of surgically made alternative CSF pathways (so-called endoscopic ventriculostomy, see also section “Endoscopic methods”).

Fig. 8

MRI, sagittal T2. There is a flow void signal seen in the foramen of Monro (left arrow), while the entrance to the obstructed Sylvian aqueduct is dilated and lacking a flow void (right arrow)

Serum and CSF Markers

Mainly GCT and some of the NGGCT are supposed to produce markers, which can be detected in serum and/or CSF. Negative markers do not exclude the presence of GCT, especially determination in serum is not reliable. CSF markers have a more reliable diagnostic yield, but a lumbar puncture is critical in the majority of the cases due to the related occlusive hydrocephalus of the lesions in this area. As some of the pineal patients present with acute CSF pathway obstruction, it is mandatory to send CSF for marker analysis when performing either external ventricular drainage or a third ventriculostomy [9].

Treatment Methods

Open Surgery

Despite of the rise of minimal invasive methods, open surgery remains the favoured surgical procedure in most of the cases; especially benign lesions should be removed totally in first line. The microsurgical technique is the established common practice [6, 12, 19, 35]. Thanks to the advances in surgical techniques as well as the perioperative management the number of complications nowadays is acceptably low (Bruce and Ogden [6], see also section “Monitoring: neuronavigation”)—at least as long as the operations are performed in experienced centres. One of the main advantages of the open surgery is the possibility to remove the tumour totally, which is the main therapeutic goal in benign tumours. In all other cases, it provides the possibility to obtain a representative specimen in order to come to a reliable histological diagnosis and to reduce the tumour volume as an optimised pre-condition for a more effective adjuvant therapy [5]. Especially in the context of frequently mixed tumours (germinoma and teratoma), one may understand the importance of definitive specimens.

A positive side effect of tumour removal is the elimination of aqueductal compression and subsequent hydrocephalus, which allows for a long-term therapy without using a shunt.

As far as surgical approaches are concerned, there are many different ways to reach the pineal region. The supracerebellar infratentorial and the occipital transtentorial approaches are mentioned to be the most common ones; each method provides its advantages or disadvantages, which will be discussed below; the final choice, which approach to chose, depends on the specific anatomical conditions of the patient, the location and extent of the tumour as well as the personal experience and the preference of the surgeon performing the procedure.

Approaches

Supracerebellar Infratentorial

This approach, first described by Fedor Krause (1856–1937) in the 1920s, was optimised in the 1970s by the upcoming microsurgical techniques [53, 54]. It often is performed on the patient in semi-sitting position. Prone positioning can be chosen alternatively. This approach is strictly extracerebral and extracerebellar with no need to incise brain tissue.

Via a midline incision and a suboccipital craniotomy the dura is opened, so one may look infratentorially and above the cerebellum through the gained space into the pineal region. A thoughtful and unilateral sacrifice of cerbellar veins remains without any consequences as long as care is taken of the precentral vermian vein, which may lead upon its occlusion to cerebellar infarction (N de Tribolet, personal communication, 2011 see also Fig. 9). This approach enables the surgeon especially to have a good overview over the venous structures in this area. The cerebellum is depressed caudally due to the gravity while patient is positioned half-sitting; using a retractor can support this effect. Through this approach to the pineal region is reachable without incising brain tissue. Most authors prefer the sitting position; some also chose the prone position for this approach.

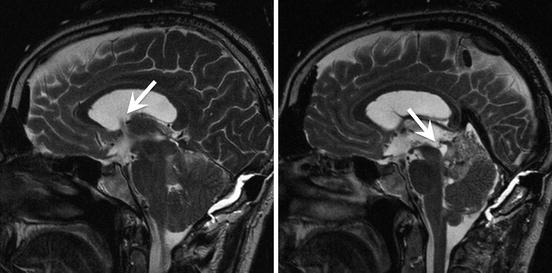

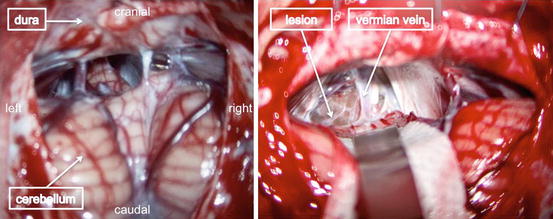

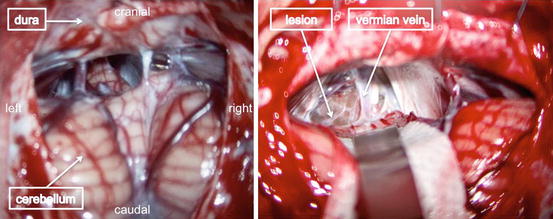

Fig. 9

Microscopic view of the infratentorial supracerebellar approach. In this case, the individually highly variable posterior cerebellar veins draining into the tentorium (left) were cut to depress the cerebellum and move the vermis sideways, leaving the rostral veins hidden in the arachnoid “curtain” behind the lesion (right) intact

Occipital Transtentorial

As an alternative a parasagittal craniotomy can be performed in the occipital region over the non-dominant hemisphere and by approaching the tentorium via a parafalcine interhemispheric route, it can be incised close to the midline. By this approach, the pineal region is reached from the dorsal upper part and consideration needs to be taken of the important venous structures of this area.

Parietal Interhemispheric/Transcallosal

Through this approach, which includes a craniotomy placed rostral to the aforementioned route, the pineal region can be reached via the midline interhemispheric space (also along the falx) and by dividing the dorsal part of the corpus callosum. Bridging veins may also appear as another obstacle. Accordingly this way is the most traumatic one among the three described approaches. Nevertheless, it may be the appropriate choice as far as lesions in the dorsal part of the third ventricle adjoining the pineal region are concerned.

Positioning

Depending on the chosen approach, the location and extent of the tumour, there are several possible ways to position the patient. The sitting/semi-sitting position, which is mentioned to be the most common one, provides better and gravity supported depression of the cerebellum [53], especially when choosing the infratentorial supracerebellar approach.

The major risk of the sitting position is that of air embolism which is all the more dangerous in the presence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO). Without PFO, a massive air embolism can lead to pulmonary problems, but with PFO paradoxical air embolism can occur anywhere including the brain. To prevent or at least anticipate these complications it is recommended to perform a cardiac sonography prior to the operation in order to recognise the existence a PFO. Positioning of the patients with legs up, head maximally anteflected and body reclined as much as possible is crucial (Fig. 10). As air enters mostly trough venous bone channels, diamond drills to finish the craniotomy and bone wax are mandatory. After dural opening, air rarely enters the circulation. Nevertheless, constant intraoperative monitoring of the right atrium by Doppler or better echocardiography is mandatory. The involvement of dedicated neuroanaesthesia is part of the interdisciplinary approach to the pineal region.

Fig. 10

Semi-sitting position of the patient with his head fixed in a Mayfield clamp

As most patients have hydrocephalus and a dilated third ventricle, which is widely opened during surgery, symptomatic pneumocephalus is a not infrequent (Fig. 11) phenomenon. It remains a case-to-case decision whether to place an external ventricular drainage at the end of the procedure because in most cases the situation will resolve within the first-day post-surgery.