Life-Limiting Illness, Palliative Care, and Bereavement

John P. Glazer

David J. Schonfeld

Pediatric Palliative Medicine

Some 500,000 children suffer from life-limiting illness and 50,000 die annually in the United States (1). This reflects two parallel trends: 1) the shift from acutely life-threatening infectious disease to chronically life-limiting noninfectious disease in pediatrics and 2) the expanding recognition of the need for, and capacity to identify and intervene with functionally impairing and distressing pain, depression, and anxiety, and the challenges to communication typical of these children and their families. Originating as “respite for weary travelers” in ancient times, the modern hospice movement began in the twentieth

century with Dame Cicely Saunders’ groundbreaking efforts at St. Christopher’s Hospice, London, on behalf of adults dying of cancer, coming to the United States in the 1970s, proliferating rapidly, and only recently extended to children (1).

century with Dame Cicely Saunders’ groundbreaking efforts at St. Christopher’s Hospice, London, on behalf of adults dying of cancer, coming to the United States in the 1970s, proliferating rapidly, and only recently extended to children (1).

The term palliative care does not appear in the indexes of the first two editions of this text. It appears in the third edition in passing reference in chapters on pain and cancer. But pediatric palliative medicine has come of age in the new millennium and is the lens through which issues not only of death and dying but the more inclusive and accurate concept of life-limiting illness is now seen. This chapter addresses the principles and practice, from a psychiatric perspective, of pediatric palliative medicine by reviewing in a biopsychosocial fashion the major elements of diagnosis and treatment of children with life-limiting illness and their families. The term “life-limiting” deserves emphasis: Himelstein and colleagues (1) state that “palliative care is appropriate for children with a wide range of conditions, even when cure remains a distinct possibility.” This broad view of palliative care, the notion that “palliative care is not all about death” (2) is recognized by the American Academy of Pediatrics practice guidelines: “the components of palliative care are offered at diagnosis and continued throughout the course of illness, whether the outcome ends in cure or death” (3). This crucial distinction recognizes both the unpredictability of medical prognostics and the role of hope, “the weight of a feather on the side of optimism” (4): the denial of hope differs from realistic appraisal and acceptance of life threat. While hospice and palliative medicine grew out of care for individuals with cancer, the scope is now much broader. Pediatric life-limiting illness is of course seen in a broad range of diagnostic categories, from cancer to chronic renal disease, cystic fibrosis, neurological disorders, mitochondrial disorders, sickle cell disease, and others. Pediatric palliative care services have recently been extended to the perinatal setting (5).

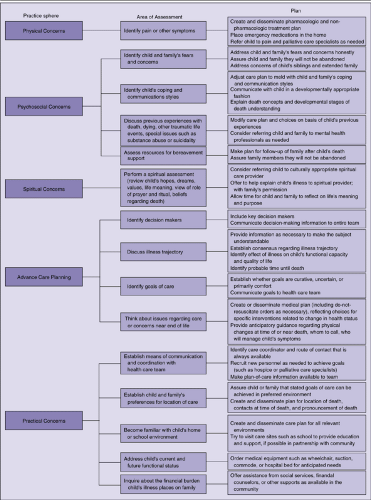

Himelstein et al. (1) have proposed the following “essentials” of pediatric palliative care (Figure 7.1.4.1): physical concerns such as pain assessment and management; 2) psychosocial concerns, including child and family fears, communication and coping styles; 3) spiritual concerns; 4) advanced care planning, including identification of decisionmakers, illness trajectory, care goals, and end of life care; 5) practical concerns regarding location of care and familiarity with the child and family’s community and school environment; and finally, 6) bereavement care for families if the child dies. Communication with and among child patient and family members, and relationships between pain and psychiatric symptom expression, are central to the focus and expertise of the child psychiatrist in a medical setting, as is the grounding of care longitudinally. As such, child and adolescent psychiatry and pediatric palliative medicine are natural partners in the management of children with life-limiting illness as reviewed below.

Scope

This chapter addresses psychiatric aspects of pediatric life-limiting illness through review of cognitive-developmental acquisition of the concepts of death, assessment, and management of psychiatric symptoms, and management of pain in the life-limited child, as well as parental loss, the psychosocial needs of caregivers, and approaches to systems of care. “Palliative care” and “bereavement” are meant as inclusive terms: As children with life-limiting illness live longer, with advances in chemotherapy, transplant technology (see Chapters 7.1.3.1 and 7.1.3.2), radiation oncology and other modalities, old distinctions blur. To palliate is to “relieve pain and distress” without cure (6); as already noted, this definition is expanded to include children with life-limiting illness who survive and those who do not. Similarly, bereavement is “a deprivation causing grief and desolation, especially the death or loss of a loved one” (6). In addition to the 50,000 children and adolescents who will face their own deaths each year in the United States, another 4% of children will lose a parent before age 15 years (7). Professionals responsible for the care of children must address the psychosocial needs of children and families in all of these settings. Speaking to the experience of children and families with life-limiting illness more than 20 years ago, Solnit wrote that “the adults and the children don’t know whether to prepare for life or for death” (4). The principles discussed here address the universal experience of separation and loss by children, whether they, their parents, or their siblings have life-limiting illness from which they may recover or die.

Children’s Concepts of Death

Children experience life-limiting illness in themselves or others through the prism of psychological, physical, and social development. Health professionals must therefore approach such children and their families with expertise in child and adolescent development and family systems (1). Central to this approach is an appreciation of the developmental acquisition of the concepts of death (8). The stages in children’s understanding of the concepts of death have been well studied (9,10,11,12,13). Four major concepts related to death have been noted consistently: irreversibility, finality (also termed nonfunctionality), causality, and inevitability (also termed universality). Acquisition over time of a mature understanding of each of these concepts inevitably shapes a child’s response to life-limiting illness in herself or loved ones. Speece and Brent (12) concluded that most studies found the age of acquisition of the three concepts they reviewed (irreversibility, nonfunctionality, and universality) to occur between 5 and 7 years; earlier studies citing an older age of acquisition typically were noted to have significant methodological flaws.

Since infants have been shown to respond to maternal depression with altered feeding patterns and failure to thrive, it is not surprising that they can similarly respond to the affective tone within the household after the serious illness or death of a family member (14). In this way, infants and toddlers are capable of reacting to someone else’s death, even if they “understand” little of what has occurred. But once infants have developed object permanence, they are capable of appreciating the permanence of loss. It is therefore probably no coincidence that infants and toddlers engage universally in the game of peek-a-boo (or hide and seek) which has been suggested may be an attempt for children to understand and cope with separation and loss. Indeed, the translation for “peek-a-boo” from Old English is literally “alive-or-dead” (15,16).

Infants, toddlers, and young children generally equate death with disappearance or separation. However, when faced with traumatic events, such as the death of a parent or other family member, some children 2–3 years of age or even younger have been able to demonstrate a beginning understanding of some of the concepts of death. In general, the role of personal exposure to the death of others has been controversial; although several studies have shown that such personal experience may promote the acquisition of the concepts of death (17,18), other studies have failed to support this conclusion (19,20). Cross cultural comparisons (21,22,23) have illustrated both cultural variations and important cross cultural consistencies, suggesting that although the underlying developmental framework is likely to be robust across cultures, sociocultural variables may have a significant impact on the rate of acquisition of individual concepts. In addition, developmentally based and conceptually focused education have been demonstrated to have a positive impact on children’s rate of acquisition of these concepts (24).

From preschool age to early childhood, children continue to clarify their concepts of death but are still confused at times, remaining prone to misconceptions and literal misinterpretations. Children in this age group with a life-limiting illness have been shown to have a marked awareness of the seriousness of their illness, even if never told that their illness is fatal, and often develop a conceptual understanding of death more typical of an older child (25,26).

During adolescence, reactions to life-limiting illness are influenced both by emerging formal operational cognitive capacities for abstract thought and by intense developmental striving for physical, sexual, social, psychological, and

intellectual independence and mastery. Life-limiting illness turns this developmental process on its head, bringing physical immobility and dependence rather than independence, isolation from peers rather than the forging of new relationships, and may stop educational progress in its tracks.

intellectual independence and mastery. Life-limiting illness turns this developmental process on its head, bringing physical immobility and dependence rather than independence, isolation from peers rather than the forging of new relationships, and may stop educational progress in its tracks.

Intervention

Study and recognition of the developmental acquisition of concepts of life-limiting illness and mortality by children and adolescents has led to effective tools for and approaches to intervention. The pediatric and child psychiatric literature increasingly reflect development of sophisticated, evidence guided approaches to the care of children with life-limiting illness and their families. These include the advent of multidisciplinary pediatric palliative care teams that strive to become involved early in illness trajectory (27), and specialized approaches to psychotherapy (28), among others.

Pain and Symptom Management

Pain assessment and management is at the heart of care of children with life-limiting illness. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage (29)”. This definition has much utility for psychiatrists in its recognition that emotional factors are inherent and that its magnitude varies according to factors not limited to the extent of measurable tissue damage.

The historic undertreatment of pain in children and its adverse medical and emotional consequences is well documented (30). Eland’s pioneering work in the 1970s (31) found in a chart review that of 25 children undergoing major surgery (traumatic amputation, nephrectomy, cleft palate repair) at a major children’s hospital, 13 received no postoperative analgesia at any point in their hospital stay. Among the 12 children who did receive analgesic drugs, only 24 total doses were given, compared to 372 opioid and 299 nonopioid analgesic doses given to a comparison series of 18 adult postoperative patients. Reflecting prevailing attitudes toward the experience and management of pediatric pain, Swafford and Allen reported that just 26 of 180 children (14%) admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit over a 4 month period “required” opioid analgesia, stating “pediatric patients seldom need medication for the relief of pain. They tolerate discomfort well. The child will say he does not feel well or that he is uncomfortable, that he wants his parents but often he will not relate the unhappiness to pain” (32).

Pediatric pain management has improved with time, particularly after Anand and colleagues’ influential studies in the 1980s showing that preterm infants undergoing surgery with minimal anesthesia exhibited marked, physiologically documented stress responses, with adverse effects on morbidity and mortality (33). However, adequate pain management in children with life-limiting illness continues to be a major challenge, best documented in children with cancer. Wolfe et al. (34) interviewed parents of 103 children dying of cancer at a major pediatric oncology center between 1990 and 1997 a mean of 3.1 years after the child’s death, regarding symptoms and suffering experienced in the last month of life. Of the 103 children, parents reported that 80% were treated for pain in the last month of life but only 30% were treated “successfully.” Noting that palliative care is now an expected standard, the authors caution that it is unclear whether the care of children with cancer meets that standard, concluding that “89 percent of the children experienced substantial suffering from at least one symptom, most commonly fatigue, pain, or dyspnea,” treatment was “seldom successful, even in the case of symptoms that are typically considered to be amenable to treatment” (34) .Pain may mimic “psychiatric” symptoms (35); thus, in the psychiatric assessment of children with life-limiting illness, cancer or otherwise, pain assessment and management is a critical component.

Assessment

Pain assessment in children with life-limiting illness has recently been reviewed (36). As noted by Schechter (37), while developmentally appropriate assessment is the “cornerstone” of pediatric pain management, the advent of developmentally sensitive instruments is recent and challenges remain, including the limited capacity of younger children to report pain directly. McCulloch and Collins (36) include the following major factors in clinical pediatric pain assessment: 1) developmental stage, 2) intelligence, 3) personality, 4) temperament, 5) previous pain experience, 6) expectation and acceptance of pain, 7) child and parent coping strategies, anxieties, and cultural background, and 8) prognosis. Clinical studies suggest that most children can identify presence and location of pain by age 2, pain intensity by age 4 (36, 38,39,40), can participate in formal pain ratings by age 5, and describe the quality of the pain experience by age 8 (36, 41,42,43). Gaffney et al. (44) conceptualize pain measurement as “the application of a specific metric to some dimension of pain,” note the challenge that pain is inherently subjective, and point out two fundamental assessment dimensions: 1) the sensory dimension of intensity, and 2) the affective dimension of level of distress. Any pain measure must specify what it is measuring.

In clinical settings, pain in children age 8 or older is typically assessed using a 10-point visual analog scale with “no pain” at one end and “most pain imaginable” at the other, with or without numerical gradations from 1–10. In Piagetian terms, 8 year and older preadolescent children at a concrete operational level of cognitive development would be expected to have a simple, internalized symbolic capacity to rate pain severity, thus the utility of numeric visual measures (36). Several well validated measures appropriate for preoperational 3–8 year old children have been developed, using cartoon faces at graded pain intensity (45), photographed faces (“Oucher” scale (46)) and poker chips (“pieces of pain (47)”). Pain measures developed for relatively healthy children (after surgery, for example) may be invalid when applied to seriously ill children (48). Fortunately, a measure specifically applicable to children with cancer as young as age 2 is now available (50). Performing any pain assessment in pediatric palliative medicine remains an unmet challenge: A Canadian chart review study found documentation of pain assessment in only 5 of 77 children (6%) who had died in the hospital (51).

Treatment

Pharmacologic

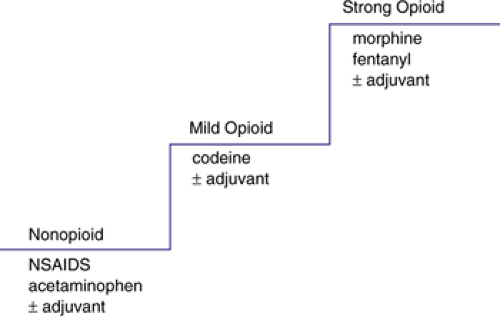

The cornerstone of addressing pain pharmacotherapy in adults is the analgesic ladder of the World Health Organization (52) shown in Figure 7.1.4.2, and is applicable to children (52,53).

The WHO analgesic ladder grades pain severity and matches an analgesic category to each level: Acetaminophen or another NSAID for mild pain, the “mild” opiate codeine for mild to moderate pain with or without an adjuvant, and the potent opiates morphine or fentanyl with or without adjuvants

for moderate to severe pain. Caveats include avoidance of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) due to antiplatelet effects, agonist/antagonist opioids because of their ceiling effect, and the opioid meperidine (Demerol) because of toxic metabolite accumulation with extended use (54).

for moderate to severe pain. Caveats include avoidance of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) due to antiplatelet effects, agonist/antagonist opioids because of their ceiling effect, and the opioid meperidine (Demerol) because of toxic metabolite accumulation with extended use (54).

FIGURE 7.1.4.2. The analgesic ladder. (Adapted from World Health Organization Ladder: Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care, Technical Report Series 804. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1990.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|