CHAPTER 3 Lifespan

middle and later years (adulthood to ageing)

The material in this chapter will help you to:

♦ Lifespan development – middle and later years

♦ Employment, career and lifestyle

♦ Chronic and other health issues

Introduction

As is common among researchers and theorists, adulthood is often broken into stages. Most commonly this is into stages of early, middle and late adulthood because they show major differences in physical, social, emotional and cognitive abilities as well as circumstances. Theorists have observed quantum changes in how people behave across these periods. The transition from adolescence to adulthood is referred to as emerging adulthood (Arnett 2000, Arnett & Tanner 2006). In this chapter, we will focus on adulthood as the time in a person’s life in which they have taken on greater responsibility, whether through employment, marriage, having children or living away from primary caregivers. The time at which these events occur varies substantially in different people’s lives and it is therefore essential to have an understanding of the various conceptions of age, such as chronological, psychological, social and biological.

Chronological age is the concept that is almost exclusively used in healthcare practice but it is not without its limitations. Because of the extreme variability in the health of older people, some have argued that healthcare should not be related to chronological age but, instead, should be relevant to need, health conditions or biological age. For example, because policies are related to healthcare provision relevant to specific chronological ages (e.g. various cancer screening programs are only available for certain age groups), those who do not ‘fit’ in this conception (e.g. residents from refugee backgrounds or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with chronic conditions) can miss out on important healthcare.

Theories

The theories of human development usually outline various stages of life pinned to chronological ages but others have argued that imposing chronological age on human development is imprecise at best (Hendry & Kloep 2002). We will look at some of the stage theories while bringing in other views of what human development looks like.

Erikson’s theories

Most often when we think of theories of human development relevant to adulthood we think of Erik Erikson, who is probably the most well known psychologist with a theory of development that extends into adulthood. Other theorists, such as Freud and Piaget, only extended their theories to puberty (Freud’s genital stage) and around age 11 (Piaget’s stage of formal operations. See Chapters 1 and 2 for more information). Perhaps the complexities with adulthood and the lack of well-defined, discrete, developmental stages directly related to age have challenged theorising in this area. In this section, we will review Erikson’s theory and will also explore Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory, Kohlberg’s theory of moral judgement, Baltes’s theory of selective optimisation with compensation and the lifespan model of developmental challenge.

The main stages of Erikson’s theory relevant to adulthood are the stages of intimacy versus isolation, generativity versus stagnation and integrity versus despair (Erikson 1950, 1982, Erikson & Erikson 1997) (see Table 3.1). Table 2.1 in Chapter 2 lists the first five stages of Erikson’s theory.

Table 3.1 Erikson’s final three developmental stages

| ERIKSON’S STAGES (FINAL THREE ONLY) | DEVELOPMENTAL STAGE (AGE) |

|---|---|

| Intimacy versus isolation | Early adulthood (20s, 30s) |

| Generativity versus stagnation | Middle adulthood (40s, 50s) |

| Integrity versus despair | Late adulthood (60s onwards) |

The stage of intimacy versus isolation is characterised by either the seeking of companionship and intimate love with another person or becoming emotionally isolated and fearing rejection or disappointment. This stage is usually said to occur during early adulthood and is often associated with the chronological ages of 18–24 years. In terms of healthcare practice, recognising that people at this stage may be struggling to come to terms with intimacy issues and that multiple factors can contribute to isolation, health professionals can serve a very useful role in assisting clients to successfully resolve this stage. For example, linking clients with support services, community organisations or self-help programs and groups can go a long way in preventing issues that could become more serious if left unrecognised. This is supported by considering the relationship between social isolation and mental disorders such as schizophrenia (e.g. Cantor-Graae 2007) and that three in four mental disorders occur before age 24 (Kessler et al 2005).

Kohlberg’s theories

Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning (1976) includes three levels and six stages roughly from age four to adulthood. Level I, or preconventional morality, includes stages 1 (orientation towards punishment and obedience) and 2 (individualism and exchange). Level II, or conventional morality, generally relates to children aged 10–13 and includes stages 3 (maintaining mutual relations and approval of others) and 4 (social concern and conscience or maintaining the social order). Level III and stages 5 and 6 are most relevant to adulthood and healthcare, although Kohlberg postulated that some people never enter these stages. Level III, or postconventional morality, includes stage 5 (social contract or individual rights and democratically accepted law) and stage 6 (morality of universal ethical principles). In stage 5, people are rational and can be thoughtful and critical of laws and legal issues but inevitably will conform to laws and human rights as morally ideal. In stage 6, however, universal ethical principles will outweigh legal concerns in a moral dilemma. Kohlberg also later included a stage 7 (the cosmic stage) in which people would be able to see the impact of their action on the greater world, rather than only their immediate world (Kohlberg & Ryncarz 1990).

In terms of healthcare, the relevance of Kohlberg’s theory is obvious. There are many moral and ethical dilemmas that health professionals contend with on a regular basis and the resolution of these dilemmas will partly depend on where a person is at in terms of these stages and how the dilemmas are resolved. But it is perhaps too restrictive to just view these as internal stages of moral development. Dealing with moral dilemmas regularly and the social and structural systems in place to facilitate this, such as the quality of debates with coworkers or the policies in place surrounding moral dilemmas, will influence the resolutions of these dilemmas. Take, for example, the issues of euthanasia or, for a less contentious issue, the use of medication that has serious side effects. Kohlberg is saying that how you decide these issues can change with a more or less developed sense of moral

Table 3.2 Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning

| LEVEL I: PRECONVENTIONAL | |

| Stage 1: | Punishment and obedience |

| Stage 2: | Individualism and exchange |

| LEVEL II: CONVENTIONAL | |

| Stage 3: | Maintaining mutual relations and approval of others |

| Stage 4: | Social concern and conscience or maintaining the social order |

| LEVEL III: POST-CONVENTIONAL | |

| Stage 5: | Social contract or individual rights and democratically accepted law |

| Stage 6: | Morality of universal ethical principles |

| Stage 7: | The cosmic stage: able to see impact of actions on the greater world |

reasoning and so health professionals need to consider all forms of reasoning and not just believe there is only one right or wrong answer to euthanasia or medication.

Others’ theories

Limitations to these classic theories have pushed the need for theories that are more contextual and not so limited to Western notions of individuality and chronological age (Qin & Comstock 2005). These more recent theories include the ecological approach of Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979, 2004), Paul Baltes’s lifespan perspective (Baltes 2000, Baltes & Baltes 1990, Baltes et al 2006) and the lifespan model of developmental challenge (Hendry & Kloep 2002).

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979, 2004) theory takes individual development into a wider social context, considering micro (e.g. family and work), meso (the interactions between the individual’s social connections, e.g. your mother interacting with your partner), exo (which are the social connections that the individual’s social connections have, e.g. your partner’s work colleagues) and macro systems (e.g. religion and politics). Bronfenbrenner’s system, also called a ‘bioecological’ system, is multidirectional in that it is not only the social systems that impact on the individual but that the individual also impacts on those systems. ‘Development is not something that just “happens” to the individual person but an interactive, dynamic process that involves all the system levels of a society’ (Hendry & Kloep 2002 p 12).

Lifespan perspectives, or lifespan theories, of human development consider development across the full lifespan and suggest that to fully understand someone’s development, one needs to consider how life events influence development. The lifespan perspective also considers the important social and political factors that impact on development such as policies impacting on Aboriginal Australians (such as the ‘stolen generations’) or economic conditions (such as post–Second World War depression). In Baltes’s lifespan theory, a further dimension relates to how gains and losses in life contribute to change and development (Baltes 2000). Overall, greater gains and fewer losses result in positive development (Baltes at al 2006).

Carol Gilligan is a human development theorist who argued that human development theories (especially Kohlberg’s) do not adequately account for development as it relates to girls and women. In her research with pregnant women contemplating abortion, she found that conflicts with responsibility to self and to others related to moral development for women that is not adequately addressed in Kohlberg’s theory. Overall, Gilligan found that morality for women relates to an ethic of care and suggested that differences between men and women should not be minimised (Gilligan & Farnsworth 1995). Although some research has shown that Gilligan’s critiques of Kohlberg’s theory were unjustified, her theorising drew attention to the often male-dominated theorising in human development.

Another female theorist in human development is Marion Kloep who, with Leo Hendry, has recently proposed the lifespan model of developmental challenge (Hendry & Kloep 2002). In Hendry and Kloep’s lifespan model of developmental challenge, the concepts of challenges, resources, stagnation and decay feature prominently (2002). Basically, in this model, people have ‘potential resources’, and these resources influence how an individual will respond to various challenges (‘potential tasks’) that will occur throughout life. Resources include an individual’s biology, social resources, skills, self-efficacy and structural resources. An interesting feature of the developmental challenge model is the relationship between task demands (whether there are many or few) and the availability of resources and how they relate to feelings of anxiety or security and whether the task is then a risk, a challenge or routine. If tasks are often routine and the resources exceed the task, then stagnation can result. Also, if there are not enough resources and the tasks are risky, then decay can result.

Milestones of adulthood

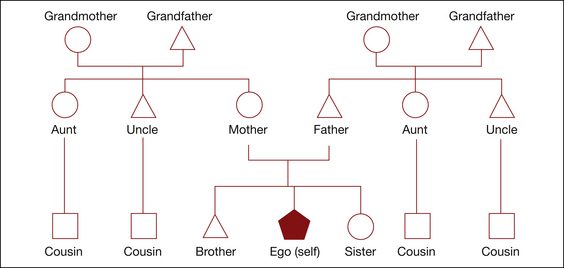

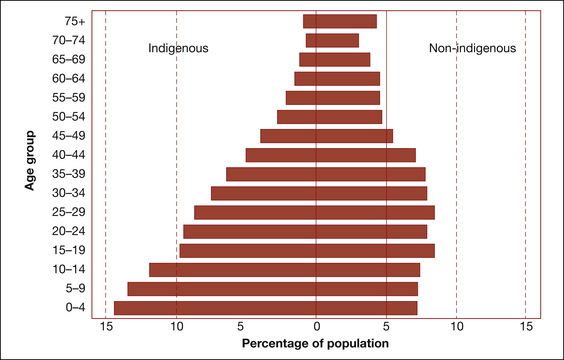

A good way to start viewing ageing is to look at the statistics or the demography. What you will first notice is that different groups have different age structures. This is shown in ‘population pyramids’ such as depicted in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Populaton pyramid of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, 2006

Source: HealthInfoNet 2008

Figure 3.1 illustrates the percentage of the population in five-year age groups for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population of Australia. We can deduce from this figure that the social issues for human development might vary considerably for Indigenous or non-Indigenous Australians. For example, while non-Indigenous Australians have a greater proportion of people in the middle-age groups, most Indigenous Australians are represented in the youngest age groups. The social impact of that is the greater demand on older Indigenous Australians for child care (compared with non-Indigenous Australians) but greater demands on non-Indigenous Australians for elderly care. While this is straightforward in some ways, many social scientists have tried to impose theoretical structures onto the development span and try to embrace the whole process of development across an individual life but this information shows that development and other factors cannot necessarily be separated.

Marriage and family

With the religious and cultural diversity of Australia, mate selection, marriage and family are correspondingly diverse (Hartley 1995). We might generally think that differences in marriage fall into distinct categories of ‘love marriages’ or ‘arranged marriages’ or we may have ideas about what it is that makes up a family. A family, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), is two or more persons, one of whom is at least 15 years of age, who are related by blood, marriage (registered or de facto), adoption, step or fostering and who are usually resident in the same household (ABS n.d.) This definition is a very Western conception and revolves around the concept of the ‘nuclear’ family. The ABS also identifies couple families with and without children, one-parent families, step families and blended families but these, too, are basically ‘nuclear’ family conceptions. However, how families are conceptualised can differ quite drastically in different ethnic groups. For example, for some, the ‘family’ would not exclude those who ‘are not usually resident in the same household’ and the relevance of the ‘household’ may have different meanings for different people and groups.

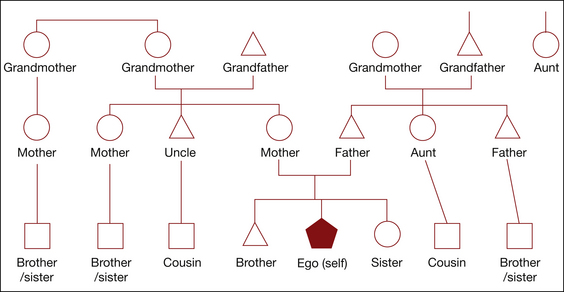

There are also differing notions of relatives that are important for health professionals to recognise. For example, consanguineal kin are people who are related by blood, ancestry or descent and affinal kin are people who are related by marriage. In-laws and their relatives are therefore affinal kin. Adopted kin are family created through adoption and fictive kin are those who you might consider to be related to you, like calling your best friend your sister. Figures 3.2 and 3.3 illustrate two alternative ways that relationships in a family can be construed. Figure 1 shows the Euro kinship pattern while Figure 2 illustrates the Dravidian kinship pattern. The Euro kinship pattern is common in Western groups, while the Dravidian system is found in South India and in some Aboriginal and Oceanic groups. These are only two kinship patterns and there are a number of other ways in which relationships between blood and marriage can be understood. However, in Australia, perhaps the Dravidian and the Euro patterns are most common.

In Dravidian kinship, a person can have multiple mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers who are outside the immediate family unit. For example, the sister of one’s mother is also called mother and the daughter or son of that mother is called a brother or sister. In terms of parenting (discussed next), this kinship pattern can be very useful, for example, if a teenage boy is getting into trouble, then another father may be called on to offer guidance. In terms of healthcare, a mother’s sister may take children to healthcare appointments in her role as another mother. Another characteristic in Aboriginal kinship systems is ‘avoidance relationships’, which is the avoidance of, or not interacting with, certain relatives out of respect. For example, a man and his mother-in-law constitutes an avoidance relationship.

Marriage in Australia is a hugely important and common event, reflected by the fact that in 2006 alone, 114,222 marriages were registered (ABS 2007). Although, historically, the number of marriages in Australia has decreased, they have slightly increased in the past few years. Age at marriage, on the other hand, has been steadily increasing, with the current median age at marriage 29 years for women and 31 years for men. Living together before getting married (i.e. cohabitating) is now a very common practice with 76% of couples reporting cohabitating prior to marriage. One drastic change in marriages over time is that marriages are much more likely now to have been performed by civil celebrants rather than religious ministers. While the majority (61%) of marriages in Australia are between men and women who were both born in Australia, 30% were between men and women born in different overseas countries and 9% were between couples born in the same overseas country (ABS 2007).

Marriage is an important consideration of health professionals because of the research showing various relationships between marriage (or being single) and health (Jaffe et al 2007). For example, people who are married have a longer life expectancy, ‘Marriage reduces the risk of an earlier death as a person is less likely to participate in risky behaviour and more likely to nurture or “guardian” each other’s health through promoting good diet and physical care’ (Elliot 2008 p 1). A large study in the United States by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2004) found that married people were overall (except in bodyweight) healthier than people who are not married. This better health includes being less likely to suffer various conditions such as headaches or back pain, as well as lifestyle factors such as not smoking, drinking alcohol or being physically inactive. Married men, however, were more likely to be overweight. Interestingly, the patterns did not hold for people who were living together but not married whose health was similar to the poorer health reported by divorced or separated adults (CDC 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree