CHAPTER 2 Lifespan

the early years (birth to adolescence)

Introduction

Numerous theories and stage models have been proposed to describe the years of life from birth to adolescence (Damon & Lerner 2006, Harms 2005). Rather than learn these exhaustively, it is more important to understand the broad changes that can be observed across these years when watching children. These observable changes contributed to what researchers have proposed are important for health professionals to remember when working with children.

CLASSROOM ACTIVITY

EXERCISE 1

Each person considers their own experiences with children and identify for each age group:

EXERCISE 2

If you need more structure, consider that theorists have often broken behaviour patterns into:

Outline the changing patterns you have observed across ages in these five domains.

Types of theorising about development

There are many ways to categorise theories: reductionistic, mediational, deterministic, essentialistic, causal, contextual, explanative or descriptive. A reductionistic theory, or reductionism, is a theory in which complex things are reduced or understood in terms of basic, simplified elements. For example, risk-taking behaviour of adolescents would be understood in terms of brain development in a reductionistic theory. Specifically, research has shown that the prefrontal cortex, which is considered to be the site of higher-order cognitive functioning (i.e. the ability to think things through), is not yet fully developed in adolescents (Nelson 2003). A mediational theory is somewhat similar to reductionism but the key element in mediationism is that a behaviour or concept is mediated by something else. Using the example of adolescent risk taking, a mediationist would say that brain development mediates risk-taking behaviour. Another example would be that an adolescent who is observed to be sleeping excessively, lacks interest in things they used to enjoy and spends a lot of time alone is then considered to be depressed, such that depression is then seen as the mediator of these behaviours. This is an important distinction because it influences how we then go about intervening or what we do to change the behaviour. Do we change the sleeping, lack of interest, the time spent alone or the depression?

Determinism is a theoretical approach in which the behaviour we observe is determined by past history: history of relationships (e.g. parental relationships in the case of Freud) or in history of consequences of behaviours (in the case of the behaviourism of B F Skinner discussed later). Using the above examples, risk-taking behaviour may be explained in a deterministic way by referring to the history of consequences of behaviour, specifically, that risk-taking behaviour has been positively reinforced, perhaps by getting attention. In contrast, essentialism views characteristics of groups (e.g. groups based on ethnicity, gender or age) as fixed or unchangeable, so, risk taking by adolescents would be seen as an essential quality or characteristic of adolescents that is not changeable or influenced by context.

Sigmund Freud is probably best known for his theories of psychoanalysis but the broad idea he championed and strongly argued was that events that occurred in childhood determined a lot of behaviour patterns later in life (Freud 1917, also see Chapter 1). In his clinical practice, Freud talked to many hundreds of people and believed there was a pattern in which some serious events in people’s early history made them into a certain type of person that continued later in life. This was connected to key events in childhood, he thought, such as learning to control eating, drinking and defecating (potty training), learning about genitals and learning the rules about them (‘you are punished if you touch them’) and learning about family control – which was almost completely controlled by the father in Freud’s day, at least for the sorts of families he dealt with.

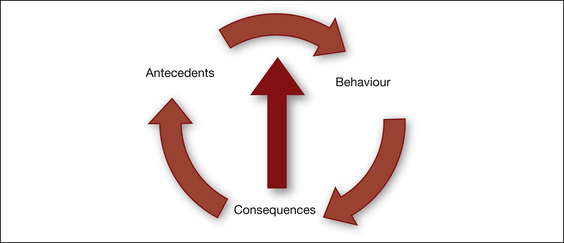

Burrhus Frederick Skinner (Fred) (1938, 1957, 1969) was a famous psychologist who mainly worked with animals. What he found fascinating was that minute details of the animal’s environment (primarily their cages and the lights and switches in their cages) could be shown to change how the animals behaved. Skinner’s theory, known as radical behaviourism, includes and elaborates on the basic concepts of antecedents (environments, contexts or stimuli), behaviour and consequences (what happens when a behaviour occurs). For example, rats that, when a light is on (antecedent or stimuli), had to press a lever (behaviour) more than once to get food (consequences) (as is the case in fixed or variable schedules of reinforcement) would persist in pressing the lever longer when the food supply was stopped (called extinction) compared with those rats that got food on every press they made (i.e. in continuous reinforcement). Skinner was impressed that these small and not easily observed changes in the animals’ environment could make a large difference to their behaviour. Figure 2.1 shows how antecedents (or the environment) can influence behaviour that then leads to a consequence. These consequences contribute to both changing the environment as well as changing behaviour.

Skinner’s work and observations with children and human participants was mostly in relation to his own children. Perhaps his best known work with children was his development of an air crib for his own child. Skinner believed that a highly controlled environment would eliminate the mundane tasks of baby care such as keeping them warm and clean. In this way, parents could more effectively (and would have more time to) engage in other aspects of parenting such as playing and reading.

B F Skinner’s original air crib can be viewed at: http://www.coedu.usf.edu/cybertutorial/images/babyinbox.jpg.

The original testing ground for Skinner’s ideas about human behaviour in research was looking at what controls our talking and use of language (Skinner 1957). Some said that no observable environmental changes could be seen when children start talking or using language in subtle ways but Skinner said that we have not been looking in the right places. Although his version of how we might look for environmental factors was not well received (e.g. Chomsky 1959), newer versions of Skinner’s ideas have been developed (Andresen 1990, Catania 1997, Hayes et al 1994).

Jean Piaget (1952, 1954, 1962) was the most famous psychologist to look at how children think (cognition) and speak (language). He was not looking for environmental factors but was more interested in theoretical ideas of ‘information processing’ centres and ‘cognitive processes’ in the brain.

While Piaget had a number of stages and substages of cognitive development, here we focus on the overall changes he noticed. (You may like to refer to a developmental psychology textbook such as Peterson 2004 for more details.) The first broad stage he called sensorimotor because children at this age think, as it were, through their senses and their physical movements. Something like, ‘If I can’t see it, taste it or touch it then it does not exist and I cannot think it!’ Children explore and learn only what they physically interact with thorough their senses. At this stage, children cannot ‘think’ a cat being somewhere else if it is not in front of them, or they are not touching it, or they do not have its tail in their mouth.

The ability to complete complex tasks or abstract ways of thinking arise in the formal operational stage in which abstract thinking is possible and can be used in reasoning and logical processes. Piaget, as well as other child development researchers, devised a number of tests to determine development at this stage and it is not so much the resolution to these tests that is important but, rather, how children come up with the resolution. For example, to combine a yellow solution with a blue solution to create a green solution, a child in the concrete operation stage may, through trial and error, mix the solutions together. However, a child in the formal operational stage may use logic to come up with the answer before using trial and error.

One thing Piaget did consistently was to focus his observations and theorising on individual children thinking and talking about events and treated the stages he saw as changes in internal information processing or the ‘structure’ of cognition. Lev Vygotsky (1978), a Russian theorist in the early 1900s, was the first of a series of theorists who, like Skinner, undertook research that looked for environmental or external factors that might be controlling the changes that appeared to occur ‘within’. However, Vygotsky did not know Skinner’s work even though it came earlier; Vygotsky’s work was not known in English-speaking countries until much later.

This sort of idea, looking at social influences on what seem to be purely ‘internal’ thinking events, has been developed in various ways, from looking for patterns in social relationship thinking that facilitate thinking about causality or mathematics, to looking at how social support, encouragement or training facilitates cognitive thinking. We still have some way to go in describing the finer details of these approaches (Guerin 2001, 2004).

The Vygotskian answer to the question of ‘What cognitive stage is that child up to?’ is: ‘Well, it depends on who that child has been interacting with and has been supported by. By themselves they might not be showing too many thinking skills but when interacting with a parent or a favourite carer or teacher they might show remarkable cognitive prowess’. In essence, the answer is in the environment (social environment), not inside the child.

Some recent approaches to describing human development have set similar ideas within multidimensional approaches. This means that human biology, social factors, psychological factors, spirituality, structural issues and culture are all considered when trying to understand human development (Harms 2005). Some call these approaches biopsychosocial models, ecological approaches or contextual approaches. What they all try to encapsulate is that human development is obviously made up of lots of changes, that most of the determinants of these changes are difficult to observe easily and that the changes all involve the body, the environment and the social world. We do not yet know how these elements might all fit together but these approaches are sure that we must have them all as ingredients.

Overall development

Much of the theorising and research we have discussed so far revolves around the development of thinking and social relationships. Others have tried to characterise the entire development sequence and put it into stages. Sometimes this is called lifespan development (e.g. Santrock 2008). In this regard it is worth looking at the model of Erik Erikson since he also proposed a very different and interesting sort of stage theory.

Instead of proposing a series of stages we all purportedly travel through, Erikson suggested a series of life conflicts, tasks or issues that we all must deal with at different ages. These can have good outcomes or poor outcomes depending upon the environment and the previous history of the individual. He proposed eight stages from infancy through to late adulthood (60 years old and beyond), although we will only look at the first five that are relevant to childhood development (see table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Erikson’s first five developmental stages

| ERIKSON’S STAGES (FIRST FIVE ONLY) | DEVELOPMENTAL STAGE (AGE) |

|---|---|

| Trust versus mistrust | Infancy (first year) |

| Autonomy versus shame and doubt | Late infancy (years 1–3) |

| Initiative versus guilt | Early childhood (years 3–5) |

| Industry versus inferiority | Middle and late childhood (years 6 to puberty) |

| Identity versus identity confusion | Adolescence (years 10–20) |

During infancy, according to Erikson, the main hurdle is to develop a basic sense of trust in people and the world, as against a basic mistrust. His idea was that if the social environment or context was not set up optimally then the individual would go through most of life always with a sense of not trusting and therefore not willing to risk events with other people. This would mean that opportunities would be lost. For example, in Vygotsky’s sense, the person would always have less cooperation with other people and so not extend themselves through social support, which would then detract from their cognitive and social development. It is not so much mistrusting that is the problem but the opportunities for further development that get restricted if a basic trust in people and the world is not present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree