(1)

Princeton Spine & Joint Center, Princeton, NJ, USA

A lumbosacral radiculopathy is commonly referred to by patients and doctors alike as a “pinched nerve” or “sciatica.” Translated from Latin and Greek, a radiculopathy is simply a pathology (pathos from the Greek) of a nerve root (radix from the Latin). A true radiculopathy means that there is neurologic loss of the spinal nerve, meaning loss of strength or sensation. A radiculitis refers to inflammation of a spinal nerve and can result in only pain or the subjective sensation of numbness, tingling, or even subjective weakness as opposed to objective loss of sensation or strength on physical examination. For the purposes of this chapter, we will consider a lumbosacral radiculopathy and radiculitis together under the term lumbosacral radiculopathy, meaning impingement and/or inflammation of one or more spinal nerves in the lumbosacral spine.

A lumbosacral radiculopathy may result from many causes. Anything or things that inflames or compresses a nerve root may result in a radiculopathy. The most common of these factors are facet joint arthropathy and/or herniated discs, but a facet joint cyst, scar tissue from a previous surgery, or a buckled ligamentum flavum could also create the conditions that lead to a lumbosacral radiculopathy. In younger patients, an acute herniated disc is more common as a cause. In older patients, a confluence of degenerative spinal factors is more common as a cause.

Common symptoms of a lumbosacral radiculopathy include one or more of the following symptoms: radiating leg pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness. It is important to recognize that while a radiculopathy may be associated with lower back pain, it is not in and of itself a typical direct cause of lower back pain. A herniated disc may inflame or compress a nerve root causing a radiculopathy. However, it is important to remember that a herniated disc may, and commonly does, exist in a person with no symptoms whatsoever. Facet joint arthropathy, facet joint-derived cyst, spondylolisthesis, and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy and buckling all may contribute to foraminal stenosis that may result in a radiculopathy – although again all of these changes may happen in someone who is completely asymptomatic. Often, a disc may cause lower back pain in addition to inflaming a nerve root in which case the pain is multifactorial. Additionally, in the presence of a radiculopathy, the muscles may spasm and guard leading to secondary lower back pain.

Consider the following patient: Anastasia is a 52-year-old violinist who presents with a 3-month history of right lower back pain radiating into the right posterior and lateral thigh and into the posterior and lateral calf and into the lateral and dorsum of the foot and big toe. The pain is described as burning. She sometimes feels numbness in the right foot. She denies any weakness. The pain and numbness is worse with prolonged sitting and better with standing and walking around. She rates the pain as 6/10 on VAS. On physical examination, Anastasia has a positive straight leg raise at 40° and has 4+/5 strength in the right hip abductors, extensor hallucis longus (EHL), and plantar flexors. Otherwise, she is neurologically intact. Her right L4, L5, and S1 paraspinals are tender as is her right quadrates lumborum muscle and piriformis muscle. She has pain at 30° of trunk flexion and feels better with trunk extension, including with oblique trunk extension bilaterally.

Most spine specialists would immediately agree and recognize that Anastasia is suffering from symptoms most consistent with a radiculopathy that is likely affecting her right L5 and S1 spinal nerves. Radiculopathies are relatively common with some estimates of them affecting 1 in 20 people [1]. When there is inflammation along the nerve root, it is not uncommon for the muscles to spasm and/or tighten along the distribution of the nerve. For this reason, the piriformis muscle (as well as muscles in the lower back) is often very tight and tender in patients with L5 and S1 radiculopathies.

A historical common pitfall in the diagnosis of lumbosacral radiculopathies was that the examining physician would press on the piriformis muscle on examination and find that it reproduced some of the patient’s pain. A presumptive diagnosis of piriformis syndrome was made followed by an injection of lidocaine and steroid into the piriformis muscle. The injection into the piriformis muscle often led to temporary relief of some of the symptoms leading physicians to label the pain confidently as “piriformis syndrome.” However, the pain would typically recur a week or two later because in most cases (>98 %) the piriformis muscle in spasm was a symptom of the problem rather than the underlying cause. As our understanding of the spine has evolved, this has become clear and by healing the L5–S1 nerve roots, the piriformis muscle typically relaxes and is no longer symptomatic without ever having to inject it.

A clinical pearl to consider is in the physical examination of the hip abductors. There are two good ways to assess this muscle group. The most gross muscle testing is to have the patient stand on one leg and assess if the patient falls into a Trendelenburg stance because the hip abductors do not support the patient. For more subtle testing, most physicians will have the patient lie on their side and push up, abducting their leg against the physician’s resistance. The pearl is to first bring the patient’s leg into slight hip extension before testing the abduction. Failing to do this allows the patient to inadvertently use her hip flexors in the testing, and because the flexors are a powerful muscle group, the hip abductor weakness, particularly if it is a subtle weakness, is missed.

When a radiculopathy is suspected, imaging is often indicated. The most common and valuable imaging study to obtain is MRI [2, 3]. It is important to always remember that asymptomatic findings on MRI (e.g., facet joint arthropathy, herniated disc) are common and therefore must be viewed as one piece of the diagnostic puzzle [4]. However, if the findings on the MRI are consistent with the patient’s reported symptoms and objective physical examination findings, the diagnosis is typically secured. If the MRI is not consistent with the history and physical examination, then electrodiagnostic studies (EMG/NCS) may be ordered to help determine and secure the diagnosis [5, 6]. Indeed, it is not uncommon for the MRI to be ambiguous or inconsistent with the patient’s history and physical examination findings. This point underscores the fact that most radiculopathies are inflammatory in nature rather than a true mechanical compression of a nerve root.

For most patients with a lumbosacral radiculopathy, conservative care is a helpful and appropriate first step of treatment. Physical therapy is often utilized at the outset and this will generally consist of lumbar stabilization exercises, hip stretches, and muscle balancing [7]. Passive modalities such as electrical stimulation, ultrasound, heat, and soft tissue mobilization may also be incorporated. If the pain limits the patient’s ability to participate with physical therapy or if physical therapy is not helpful, then a targeted epidural steroid injection may be used. The purpose of the epidural steroid injection is to reduce the swelling and inflammation from around the nerve root [8].

There are three modes of delivery of the steroid in an epidural steroid injection to the epidural space. This was discussed in the chapter on discogenic lower back pain but will be reviewed in this chapter again in case the reader has skipped to this chapter. The three modes of delivery include a caudal epidural steroid injection, interlaminar epidural steroid injection, and a transforaminal epidural steroid injection.

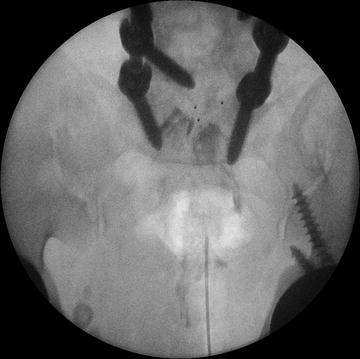

In a caudal epidural steroid injection, the medicine is delivered into the epidural space via the sacral hiatus (Figs. 10.1 and 10.2). An advantage of the approach is its relative ease of administration. While fluoroscopy is used, this approach can and is used when fluoroscopy is contraindicated or unavailable for whatever reason. However, because the medicine is starting in the sacrum, a much larger volume of medicine must be used in order to reach the lower lumbar segments, and therefore, there is a necessary and significant dilution of the steroid in the solution. Sometimes a catheter is inserted via the sacral hiatus in order to better reach the level of pathology and thus not dilute the medication as much.