(1)

Cognitive Function Clinic, Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool, UK

9.1.1 The Internet

9.1.2 The Alzheimer’s Society

9.2 Pharmacotherapy

9.2.2 Novel Therapies

9.3.2 Gardening

9.5.4 NICE Guidance (2011)

9.5.5 Dementia CQUIN (2012)

Abstract

This chapter examines various aspects of the management of cognitive disorders, including both licensed and novel treatments. The effects of a number of policy directives issued under the auspices of the United Kingdom government in recent years are examined: none appears to contribute to closure of the dementia diagnosis gap. The place of neurology-led services for dementia within an integrated dementia care pathway is considered.

Keywords

DementiaTreatmentCholinesterase inhibitorsNational Dementia StrategyIntegrated care pathwayThe management of dementia syndromes is a broad topic, encompassing not only pharmacotherapies and behavioural therapies for cognitive deficits and physical comorbidities and but also the social care context (Curran and Wattis 2004; Rabins et al. 2006; Scharre 2010; Kurrle et al. 2012). The National Dementia Strategy for England (Department of Health 2008, 2009) included amongst its objectives an information campaign to raise awareness of dementia and reduce stigma, and improvement of community personal support services, housing support and care homes. Clearly many of these objectives fall largely or entirely outwith the sphere of neurological expertise or influence (Larner 2009a). Those with a neurological training will obviously focus on pharmacotherapy, and since Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common dementia syndrome much of the emphasis here will be on the treatment of this condition. Symptomatic treatment of complicating factors (e.g. behavioural and psychological symptoms, epileptic seizures) is not discussed here (for epilepsy, see Sect. 7.2.3).

9.1 Information Seeking

With the onset of cognitive problems, and with the establishment of a diagnosis of dementia, patients and their carers may wish to seek additional information, over and above that communicated to them in clinical settings. Such sources of information include self- or relative-directed searches of the internet, and contact with patient support organisations such as the Alzheimer’s Society.

9.1.1 The Internet

The Internet is a vast resource for medical information, albeit unregulated. Studies of new referrals to general neurology outpatient clinics (n > 2,000) over the decade 2001–2010 (Larner 2006a, 2011a) have shown increasing internet access and use by patients to search for medical information prior to clinic attendance, with greatest access and use in younger patients, maximal in the 31–40 years age group, but least access and use in older people (i.e. those at greatest risk of dementia; Larner 2011a:29–30; b, c).

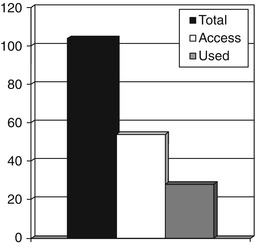

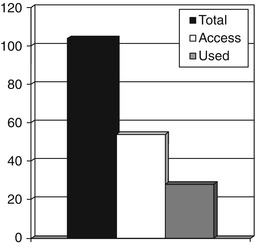

Similar studies have been undertaken to examine how often patients with cognitive problems, or more usually their relatives, use the internet to access information (Larner 2003a, 2007a, 2011a:33–4). In a study of 104 patients seen in the Cognitive Function Clinic (CFC) over a 6-month period (73 new patients, 31 follow-ups), 54 (52 %) acknowledged internet access, of whom 28 had searched for medical websites with relevant information (52 % of those with access, or 27 % of all cases). Eighty-five patients (82 %) said that they would definitely or probably access websites suggested by the clinic doctor if they had internet access (Fig. 9.1; Larner 2003a).

Fig. 9.1

Internet access and use by patients and carers, Cognitive Function Clinic, October 2001-March 2002 (Larner 2011a:34)

In a study of awareness and use of complementary and alternative therapies for dementia (Larner 2007a; see Sect. 9.3.1), internet searches for information about AD had been undertaken in 49/84 cases (=58 %), most commonly by patients’ children. The data suggested an increase in spontaneous searching for information by people diagnosed with dementia and their carers over the years (27 % in 2003; 58 % in 2007).

Reflecting the desire for information, and perhaps also the limited clinical resources available to meet the need, web-based programmes for dementia caregiver support have been developed (e.g. Chiu et al. 2009; Lewis et al. 2010; Marziali and Garcia 2011). These are designed to provide dementia caregivers with the knowledge, skills, and outlook needed to undertake and succeed in the caregiving role. The studies indicate that participants feel more confident in caregiving skills and communication with family members, and that caregivers can benefit from receiving professional support via e-mails and dedicated information web sites. In one study, an Internet-based video conferencing support group was associated with lower stress in coping with a care recipient’s cognitive impairment and decline in function than an Internet-based chat support group. Box 9.1 shows some suggestions for online resources (Larner and Storton 2011).

Box 9.1: Some Online Resources for Patients with Dementia and Their Carers (Larner and Storton 2011)

An easy-to-read A to Z of Dementia forming part of the Alzheimer’s Society’s website.

This is a clickable list of Alzheimer’s Society factsheets covering a wide range of dementia-related topics, including Genetics and Dementia, Drug Treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, and Understanding and respecting the person with Dementia. Online sheets can be downloaded free as PDF.

This page is part of the Dementia Gateway from the Social Care Institute for Excellence. It provides e-learning resources freely available to all users including a tour of the brain and how to deal with unusual behaviour; also a Dementia Glossary.

This page details how to obtain power of attorney, an issue which is extremely important to someone with dementia and their families.

The Internet has been described as a psychoactive medium, and clearly there are potential harms, as well as benefits, from internet use for those with neurodegenerative disease (e.g. Larner 2006b)

9.1.2 The Alzheimer’s Society

The Alzheimer’s Society is a charitable patient organisation which operates throughout the United Kingdom to support patients with dementia and their carers (www.alzheimers.org.uk). Despite the name, support is available to patients with dementia diagnoses other than AD, for example a number of patients with frontotemporal lobar degenerations referred from CFC have been supported through the local Alzheimer’s Society branch (Storton et al. 2012).

Only one-third of patients/carers questioned in the CFC AD outpatient follow-up clinic (July-December 2006) were aware of the Alzheimer’s Society and its work. This increased to 100 % following regular attendance of a Family Support Worker from the Alzheimer’s Society at the clinic (Culshaw and Larner, unpublished observations). Patient cohorts for studies of screening instruments may be successfully recruited through the auspices of the Alzheimer’s Society (see Sect. 5.3.2).

9.2 Pharmacotherapy

Currently the only medications licensed for the treatment of dementia are cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (Rodda and Carter 2012). Many novel therapies are undergoing evaluation. The methodology of clinical trials assessing medications for the treatment of dementia has been criticised (Thompson et al. 2012).

9.2.1 Cholinesterase Inhibitors (ChEIs) and Memantine

The existing evidence base suggests that cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) do have effects, albeit modest, on both cognitive and behavioural symptoms of AD (e.g. Lanctôt et al. 2003; Ritchie et al. 2004; Whitehead et al. 2004; Birks 2006; Raina et al. 2008) although the cost-effectiveness of these benefits has been questioned (AD 2000 Collaborative Group 2004; Kaduszkiewicz et al. 2005). ChEI trial dropouts who received active medication showed less cognitive decline at follow-up than patients who received placebo (Farlow et al. 2003). Naturalistic studies suggest that AD patients taking drugs licensed for dementia have a significantly lower risk of deterioration than those not taking these drugs (Lopez et al. 2005; Ellul et al. 2007), and their progression to nursing home placement is delayed (Lopez et al. 2002, 2005). These latter findings have prompted the suggestion that ChEIs may alter the natural history of AD, and may therefore have “disease-modifying” effects over and above their symptomatic action. However, there is no evidence that any one of the ChEIs prevent the progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD in the long term (Salloway et al. 2004; Petersen et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2007; Winblad et al. 2008), a finding confirmed by a review of multiple studies (Masoodi 2013).

With the publication of guidance by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence in 2001, ChEIs became widely available for the symptomatic treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in the UK (National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2001). Subsequent NICE guidance was more stringent in its recommendations, based on cost effectiveness analyses, thereby restricting ChEI use to moderate AD as defined by a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 10–20 (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). The most recent (and “final”) pronouncement from NICE (2011) returns to the recommendation of ChEI use in mild disease.

An audit of practice in CFC (2001–2003 inclusive), at a time when ChEI prescription was permitted in the clinic (see Sect. 1.1, Fig. 1.1), suggested compliance with the then current NICE (2001) guidance for ChEIs, as well as drug efficacy in terms of MMSE scores in the short term (up to 16 months of treatment) (Larner 2004a). The majority of AD patients remained on medication beyond 6 months, contrary to the assumption of the NICE guidance that perhaps only half to two-thirds of patients would show sufficient response with the unresponsive remainder stopping treatment (National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2001). Long term retention time has been used previously as a surrogate global measure of drug efficacy, as well as of tolerability (e.g. Nicholson et al. 2004). The possibility that this observation of high retention rate might have been related to the fact that patients in this cohort were younger than those examined in the pivotal clinical trials was considered, but in fact younger patients (<65 years of age) responded no differently to ChEIs than older patients (Larner 2004a), contrary to the findings in a prior report (Evans et al. 2000).

In the aforementioned audit, and in subsequent clinical experience, ChEIs have generally been extremely well tolerated (Larner 2004a), with less than 5 % of patients developing gastrointestinal adverse effects. These findings are commensurate with those of systematic reviews. Headache has sometimes been mentioned as an adverse effect of ChEIs (e.g. Whitehead et al. 2004), but in a cohort of 143 patients treated with ChEIs in CFC only two developed headache, and in one of these patients the symptoms were transient and did not recur on rechallenge (Larner 2006c). Use of transdermal formulations may potentially reduce adverse effects of ChEIs by lowering the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to reach Cmax but with comparable drug exposure (area under the curve) (Winblad et al. 2007; Larner 2010a).

Monitoring the treatment effect of ChEIs by means of MMSE scores (see Sect. 4.1), as recommended by NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2001; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006), is difficult to justify for a variety of reasons, including the variable natural history of AD as judged by MMSE scores (Holmes and Lovestone 2003), inter-rater errors in scoring the attention/calculation section of the MMSE (Davey and Jamieson 2004), and the inadequacy of the MMSE for detecting the small changes in cognition which ChEIs might produce (Bowie et al. 1999). This latter problem, measuring change in a manner relevant to the clinical problem of progressive dementia, was foreseen some years ago when trials of anti-dementia drugs were in their infancy (Swash et al. 1991). Another issue which may require consideration is patient anxiety in the face of cognitive testing which they know might lead to cessation of drug therapy, which might be termed an example of the “Godot syndrome” (Larner and Doran 2002).

ChEIs have also been examined in a number of other conditions which cause cognitive impairment (Box 9.2) (Larner 2010b), some in clinical trials, but in many off-licence. They have been reported to have clinical effects in dementia with Lewy bodies (McKeith et al. 2000), Parkinson’s disease dementia (Emre et al. 2004; Dubois et al. 2012), vascular cognitive impairment (Erkinjuntti et al. 2004), and multiple sclerosis (Krupp et al. 2004). A trend of efficacy of galantamine in aphasic variant FTLD has been reported (Kertesz et al. 2008) but the trial was brief and the numbers treated small. In CFC, inadvertent experience of ChEI use in FTLD (misdiagnosed as AD) has been uniformly negative (Davies and Larner 2009), and off licence experience with ChEIs in two multiple sclerosis patients with severe cognitive impairment has suggested limited efficacy (Larner 2010b).

Box 9.2: Conditions in Which Use of ChEIs Has Been Reported (Adapted from Larner 2010b)

Alzheimer’s disease (mild/moderate/severe)

Mild cognitive impairment (prodromal AD)

Down syndrome

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Parkinson’s disease dementia

Progressive supranuclear palsy

Vascular dementia

CADASIL

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

Huntington’s disease

Multiple sclerosis

Cognitive impairments in epilepsy

Delirium (treatment and prevention)

Traumatic brain injury

Sleep-related disorders: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, narcolepsy

Psychiatric disorders: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder

Cognitive disorder in brain tumour patients

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, alcohol-related dementia

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

There is evidence to support the use of memantine in AD (McShane et al. 2006; Raina et al. 2008) although NICE (2011) have ruled against its use outwith clinical trials. Combination therapy with both ChEI and memantine has been advocated, with trials suggesting both synergy (Tariot et al. 2004) and no benefit over and above ChEI use alone (Howard et al. 2012). Local funding issues have ensured that no experience has been gained in CFC with the use of memantine. Likewise, no experience has been gained with high-dose donepezil (23 mg/day), the place for which in clinical practice continues to be debated (Schwartz and Woloshin 2012; Cummings et al. 2013).

9.2.2 Novel Therapies

An increasing number of novel dementia therapies, particularly for AD, have been developed in recent years, some of which have reached clinical trials (Larner 2002, 2004b; Mangialasche et al. 2010). CFC has been involved in trials of some of these compounds through the agency of the WCNN Clinical Trials Unit (e.g. Wilcock et al. 2003, 2008). However, none have yet gained licensing approval and reached the clinical arena. Secretase inhibitors seemed to have a sound theoretical basis, designed to interrupt the biosynthetic pathway for amyloid peptides which are thought to be central to disease pathogenesis (Larner 2004b). However, the first such trialled drug (LY450139, also known as semagacestat) was withdrawn because of lack of efficacy and safety concerns (Larner 2010c; Doody et al. 2013). Treatment for other dementing conditions has lagged behind, although prion disease has evoked much research (Larner and Doran 2003; Trevitt and Collinge 2006), befitting its high public profile.

9.3 Other, Non-pharmacological, Therapies

9.3.1 Complementary and Alternative Therapies (CAT)

ChEIs are far from a complete therapeutic solution to the clinical phenomenology of AD. In the absence of other licensed treatments (as previously mentioned, memantine use has not been permitted in this jurisdiction), it is unsurprising that patients and their carers may seek complementary and alternative therapies (CAT), including “natural health products”, available on a non-prescription basis. Various CAT are claimed to help memory disorders and dementia, although the evidence base supporting this conclusion is weak (Diamond et al. 2003). Nonetheless many patients use these agents.

A study of patients (n = 84) with probable AD (time from diagnosis 3–60 months) seen for follow-up visits in CFC over a 6-month period (January-June 2006) (Larner 2007a) found that 21 (=25 %) had at one time or another used CAT for memory problems (range 1–3 medications, median 1). The most commonly used agents were ginkgo biloba (14) and vitamin E (10). Five patients mentioned that they had used omega oils (Table 9.1). Both ginkgo biloba and vitamin E have some modest evidence favouring their use in dementia (Sano et al. 1997; Oken et al. 1998; Birks and Grimley Evans 2009), although there is recent evidence that ginkgo does not reduce progression from subjective memory complaints to AD (Vellas et al. 2012) nor that it helps cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis (Lovera et al. 2012). Vitamin E may slow functional decline in mild-to-moderate AD (Dysken et al. 2014).

Heard of? | Used? | |

|---|---|---|

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) | 53 | 14 |

Silymarin | 3 | 0 |

Chotosan | 2 | 0 |

Kami-umtan-to | 0 | 0 |

Yizhi capsule | 2 | 0 |

Huperazine | 6 | 1 |

Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) | 37 | 0 |

Acupuncture | 75 | 2 |

Vitamin E | 72 | 10 |

Melatonin | 26 | 0 |

These data compare with a study from a Canadian dementia clinic which found that about 10 % of the clinic population had used complementary treatments for their cognitive problems (Hogan and Ebly 1996) and a US study of caregivers which reported that 55 % had tried at least one medication to try to improve the patient’s memory, most usually vitamins (Coleman et al. 1995). In a more recent study, just over 50 % of mildly cognitively impaired patients and their caregivers attending a memory clinic were reported to be current users of natural health products, with vitamin E, ginkgo and glucosamine being the most commonly used (Sharma et al. 2006). An Australian community-based survey found that 2.8 % of 60–64 year-olds reported using medications to try to enhance memory (Jorm et al. 2004).

9.3.2 Gardening

Gardening activities are sometimes used as an occupational therapy for patients with dementia (Heath 2004). Since physical and intellectual activities in midlife may protect against the development of AD (Friedland et al. 2001), it has been suggested that gardening may be one component of a healthy ageing programme to prevent dementia, through stimulation of the mind (Dowd and Davidhizar 2003).

A study of 100 consecutive community-dwelling patients with a diagnosis of dementia (M:F = 46:54; mean age ± SD = 65.6 ± 8.3 years; age range 44–82 years), most of whom had AD (n = 87), found that of the 38 who professed a premorbid interest in gardening, 27 (=71 %) were still undertaking some gardening activity, perhaps just “pottering”, weeding, cutting the grass, or attending to indoor plants. Cessation of gardening activity was due in some cases to loss of interest (sometimes rekindled after commencement of ChEI therapy), physical infirmity, loss of concentration, visual agnosia, forgetting the names of plants, not knowing when to plant things, and difficulty handling plants or garden implements, probably as a consequence of clinically apparent apraxia. An individualised approach tailored to cognitive abilities and deficits may therefore be required if gardening is contemplated as a component of occupational therapy for dementia patients (Larner 2005a).

9.4 Nursing Home Placement

Studies of the natural history of AD have indicated the limited value of rate of change of MMSE scores in assessing therapeutic responses (Holmes and Lovestone, 2003). Hence the use of traditional milestones as end-points, such as nursing home placement, may be more meaningful in assessing drug efficacy, although this does require longer term follow-up than in studies using cognitive, behavioural, or functional rating scales. Nursing home placement may itself be taken to reflect a measure of global patient function. Such an endpoint also has significant economic implications, since costs escalate greatly with nursing home placement. Interestingly, nursing home placement was the end-point in one ChEI trial, such that all costs accruing after this time point were censored, a policy which may have influenced the trialists’ conclusion that ChEI are not cost effective (AD2000 Collaborative Group 2004). In long term conditions such as dementia, long term studies are required in order to answer definitively such contentious issues.

An observational study by Lopez et al. (2002) came to the conclusion that ChEIs may influence the natural history of AD, over and above their recognised symptomatic effects. In this study, the frequency of permanent nursing home placement was much lower in patients receiving ChEI (5.9 %, 95 % confidence interval [CI] = 1.9–9.9 %) than in untreated patients (41.5 %, 95 % CI = 33.2–49.7 %), suggesting a long-term beneficial effect from ChEIs. However, the possibility that these findings might represent a cohort effect cannot be entirely excluded, since it would seem likely that the patients not receiving ChEIs dated from earlier in the studied epoch (1983–1999). Moreover, it is possible that earlier referral, diagnosis, support and counselling, may have contributed to the delayed institutionalization through reduced caregiver burden (Brodaty et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the figures for nursing home placement in the untreated patients were similar to those reported in a prospective study which found 35 and 62 % of “mild” and “advanced” AD cases in nursing homes after 2 years (Knopman et al. 1988). Reduced frequency of nursing home placement was also found in a study of AD patients previously commenced on donepezil as part of randomised clinical trials (Geldmacher et al. 2003). Lower risk of nursing home placement, as well as lower likelihood of disease progression, was confirmed in a further study from the Pittsburgh group examining the effects of ChEIs over 24–36 month follow up periods (Lopez et al. 2005). Long-term treatment with galantamine or other AChEIs appeared to be associated with a significant delay in the time to nursing home placement in patients with AD and AD with cerebrovascular disease (Feldman et al. 2008).

A retrospective case note audit of patients prescribed ChEIs at CFC (2001–2005 inclusive) identified 98 patients who had received ChEI for >9 months (M:F = 44:54, 45 % male; mean age at onset of treatment = 63.9 ± 7.7 years, age range 49–84 years). Of these 98 patients, 93 had AD, 60 of whom (=65 %) had early-onset AD. Other diagnoses were DLB/PDD (3) and FTLD (2). Total follow-up in this group was over 217 patient years of ChEI treatment, with mean treatment duration of 26.6 (+/–13.3) months (range 9–60 months). Eight of the 98 patients had permanently entered nursing homes during the study period (=8.2 %, 95 % CI = 2.7–13.6 %). Of these eight (M:F = 2:6), six had AD and two had PDD. Behavioural and psychological problems were the proximate reason for nursing home placement in all cases. Eight of the 98 patients, all with AD, had died during the study period (=8.2 %; 95 % CI = 2.7–13.6 %) Of these eight (M:F = 4:4), six died from causes judged AD-related (inanition, infection), two from non-AD-related causes (one from a bowel carcinoma, one from a myocardial infarction). Only one of these eight deaths was in a nursing home resident (Larner 2007b). Hence the figures for permanent nursing home placement in this cohort were comparable to those of Lopez et al. (2002) study (8.2 % vs. 5.9 %), albeit that this cohort was younger (mean age 63.9 +/–7.7 years vs. 72.7 ± 7.2 years) and that follow-up was shorter (26.6 +/–13.3 months vs. 34.6 ± 21.3 months). The lower death rate (8.2 % vs. 12.6 %) may be a reflection of the age disparities (Larner 2007b).

A reduced risk of nursing home placement has been noted in patients treated with the combination of ChEIs and memantine (Atri et al. 2008; Lopez et al. 2009), which might reflect a synergistic effect between these medications (Tariot et al. 2004) although this was not observed in another study (Howard et al. 2012).

9.5 Policy Consequences

The days when hospital clinicians were relatively autonomous practitioners and could decide, based on their experience and expertise, what was best for their patient are now, for good or ill, long past (a slightly different dispensation persists in primary care, where general practitioners are deemed to know what is best for their patients, and are therefore able to pick and choose which services they wish to use). Various documents, labelled as guidelines or guidance, yet adherence to which is mandatory rather than optional (sometimes with adverse financial consequences for non-adherence), have emerged from UK government sponsored bodies, ostensibly to render practice uniform, but in implementation to constrain doctors. The effects of these policies, easy enough to formulate, are seldom if ever examined, the hallmark of ideology, not science. Moreover a gap between policy intent and what happens in practice is well-recognised (in the bureaucratic metastory, representation is inevitably distortion). For example, use of referral guidelines for the identification of brain or central nervous system cancers (“2-week wait referrals”) usually result in the referral of patients without such cancers (Abernethy Holland and Larner 2008; Panicker and Larner 2012).

9.5.1 NICE/SCIE (2006) Guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence/Social Care Institute for Excellence (NICE/SCIE) guidelines recommended that psychiatrists, particularly old age psychiatrists, should manage the entire dementia care pathway from diagnosis to end-of-life care, acting as a “single point of referral” for all cases (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence/Social Care Institute for Excellence 2006). Neurologists were mentioned only once in the document, prompting the suggestion that the specialist dementia interests of some neurologists had perhaps been overlooked (Doran and Larner 2008). Compliance with the NICE/SCIE guidelines might have been anticipated to erode the number of general referrals to neurology-led memory clinics, and referrals to these clinics from psychiatrists in particular.

The impact of NICE/SCIE guidelines in a neurology-led memory service was examined in CFC by comparing referral numbers and source in the 2-year periods immediately before (January 2005-December 2006) and after (January 2007-December 2008) publication of the NICE/SCIE document (Larner 2009b). These data (Table 9.2) indicated a similar percentage of referrals from psychiatrists in both time periods (23 and 21 % respectively). The null hypothesis tested was that the proportion of referrals from psychiatrists (see Sect. 1.2.2) was the same in cohorts referred before and after publication of the NICE/SCIE guidelines (equivalence hypothesis). The result of the χ2 test did not permit rejection of the null hypothesis (χ2 = 0.39, df = 1, p > 0.5), a finding corroborated by the Z test (Z = 0.56, p > 0.05).

Table 9.2

CFC referral numbers and sources before and after NICE/SCIE guidelines (2006) (Larner 2009b)

Before NICE/SCIE (2005–2006) | After NICE/SCIE (2007–2008) | |

|---|---|---|

New referrals seen | 213 | 382 |

New referrals from psychiatrists (% of total) | 49 (23) | 80 (21) |

Whilst the NICE/SCIE guidelines might possibly have been instrumental in increasing the total number of referrals (see Sect. 1.1), by raising public and professional awareness of dementia, the evidence from this survey did not suggest that referral practice from psychiatry to neurology had changed in light of NICE/SCIE. The data suggested that psychiatrists continued to value access to a neurology-led dementia service and that, pace NICE/SCIE, neurologists still have a de facto role in the dementia care pathway (Larner 2007c, 2009b).

9.5.2 QOF Depression Indicators (2006)

The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) of the general practitioner General Medical Services contract in the United Kingdom (UK), introduced in April 2006, included amongst its provisions Depression Indicator 2, viz.:

In those patients with a new diagnosis of depression, recorded between the preceeding 1 April to 31 March, the percentage of patients who have had an assessment of severity at the outset of treatment using an assessment tool validated for use in primary care.

Three depression severity measures were suggested: the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module, PHQ-9 (see Sect. 5.2.2); the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); and the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II) (British Medical Association 2006).

Prior studies of non-overlapping cohorts of patients seen at CFC showed that the percentage of patients referred to the clinic from primary care who received a diagnosis of dementia was between 37 and 40 % (relative risk of dementia in primary care referrals =0.55−0.69) (Larner 2005b; Fisher and Larner 2007). Some of these non-demented patients referred from primary care may have had depression, rather than dementia, as a cause for their symptoms, and hence improvements in the diagnosis of depression in primary care, perhaps as a consequence of QOF, might have been anticipated to reduce these non-dementia referrals to CFC from primary care.

To test this hypothesis, a study was undertaken to examine whether any change occurred in the frequency of non-dementia diagnoses in patients referred from primary care before and after QOF introduction (Fearn and Larner 2009). All referrals from primary care seen in the 18 month periods immediately preceding (November 2004-April 2006) and following (May 2006-October 2007) introduction of the QOF in April 2006 were examined.

The percentage of all referrals to CFC which originated from primary care was about half (Table 9.3) in both time periods (χ2 = 0.88, df = 1, p > 0.1; Z = 0.77, p > 0.05). Of the primary care referrals, about one-third had dementia. The relative risk of diagnosis of dementia in a primary care referral pre- and post-QOF was 0.55 (95 % confidence interval [CI] 0.40–0.74) and 0.66 (95 % CI 0.49–0.89), respectively (Fearn and Larner 2009). All these findings were similar to those in previously reported cohorts from CFC (Larner 2005b; Fisher and Larner 2007).

Table 9.3

CFC practice before and after introduction of QOF Depression Indicator (Fearn and Larner 2009)

Pre-QOF (Nov 2004-April 2006) | Post-QOF (May 2006-October 2007) | |

|---|---|---|

N | 186 | 186 |

GP referrals (%) | 96 (51.6) | 105 (56.5) |

GP referrals with dementia (%) | 34 (35.4) | 32 (30.5) |

The null hypothesis tested was that the proportion of patients referred from primary care with dementia was the same in cohorts seen both before and after introduction of the QOF Depression Indicator (equivalence hypothesis). The result of the χ2 test did not permit rejection of the null hypothesis (χ2 = 0.54, df = 1, p > 0.05), a finding corroborated by the Z test (Z = 0.60, p > 0.05) (Fearn and Larner 2009).

This observational survey found no change in the frequency of non-demented patients referred to a dedicated dementia clinic from primary care following introduction of the QOF Depression Indicator which recommended use of validated scales to measure the severity of depression. Clearly this finding is subject to the caveats applicable to any single-centre study with relatively small patient cohorts, but if true may have various explanations, including lack of uptake of Indicator use in primary care in this region (very few referrals letters mentioned use of either depression or cognitive scales: Fisher and Larner 2007; Menon and Larner 2011), or inefficacy of the recommended depression severity scales to differentiate depression from dementia. For example, PHQ-9 was found to be of only moderate diagnostic utility for the differentiation of depression and dementia in a clinic-based cohort (see Sect. 5.2.2; Hancock and Larner 2009). Alternatively, methodological variables, such as sample size or the use of a surrogate measure of test efficacy (referrals to a dementia clinic as a measure for change in practice) may have caused a failure to find an effect that did in fact exist (i.e. type II error).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree