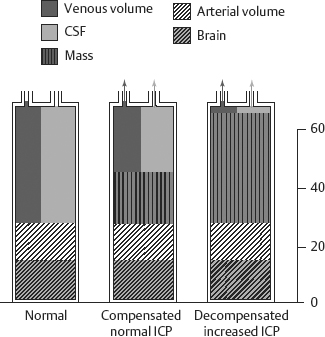

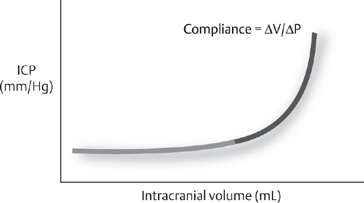

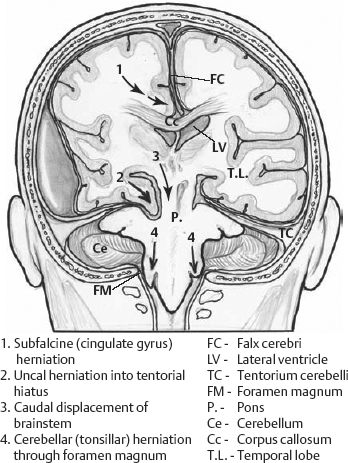

15 Management of Elevated Intracranial Pressure David Seder, Stephan A. Mayer, and Jennifer A. Frontera The cranial vault has a fixed volume comprised of the brain parenchyma (80% or ~1200 mL), blood (10% or ~150 mL), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; 10% or ~150 mL produced at a rate of 20 mL/h or 500 mL/day). Because the volume of the intracranial vault is fixed, intracranial pressure (ICP) increases when additional volume overwhelms the modest buffering capacity afforded by an extracranial shift of CSF and venous blood (Fig. 15.1 and Fig. 15.2). Pressure and volume are related by compliance (Δvolume/Δpressure). In noncompliant systems, small changes in volume will result in exponential pressure changes. Neuronal injury results from reductions in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and resulting ischemia as cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is compromised or from direct tissue compression when the brain moves along pressure gradients and herniates between fixed compartments (Fig. 15.3). Etiologies of elevated ICP are outlined in Table 15.1. Elevated intracranial pressure is a medical and surgical emergency, in which irreversible brain injury or death may be averted by timely intervention. Fig. 15.1 Intracranial pressure (ICP) compensation. Under normal conditions the cranial vault contents include the brain, arterial and venous blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). When a mass is present, extrusion of venous blood and CSF allows for a compensated ICP. If a mass becomes large enough, ICP increases. Fig. 15.2 Monroe-Kellie doctrine. Over a range of intracranial vault volumes, the intracranial pressure (ICP) remains relatively constant due to compensation, such as increased outflow of venous blood and cerebrospinal fluid. At an inflection point ICP increases exponentially when compensation measures are exhausted or in noncompliant systems. Fig. 15.3 Coronal diagram demonstrating different patterns of brain herniation.

| Primary Pathology | Examples |

| Mass lesions | Tumor, hematoma, air, abscess, foreign body |

| CSF accumulation | Hydrocephalus: obstructive or communicative (tumor, intraventricular hemorrhage, ventriculitis/meningitis, direct compression of ventricular drainage), overproduction (papilloma) |

| Vascular | Input failure (increased CBF or CBV due to exhausted autoregulation) or output failure (venous congestion or sinus thrombosis) |

| Cerebral edema Vasogenic Cytotoxic Hydrostatic Hypo-osmolar | Vessel damage due to tumor, infection/abscess, contusion Cell membrane/pump failure, ischemia Transmural pressure due to hydrocephalus For example, due to hyponatremia |

Abbreviations: CBF, cerebral blood flow; CBV, cerebral blood volume; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

History and Examination

History

Note acuity of onset: rapid onset suggests hemorrhage, acute hydrocephalus, or trauma; gradual onset suggests tumor, long-standing hydrocephalus, or abscess, for example. Previous history of cancer, weight loss, smoking, drug use, coagulopathy, trauma, or ischemic disease may point toward an etiology. Headache is caused by pressure exerted on the dural pain fibers of cranial nerve V. Nausea and vomiting are common accompaniments of elevated ICP.

Physical Examination

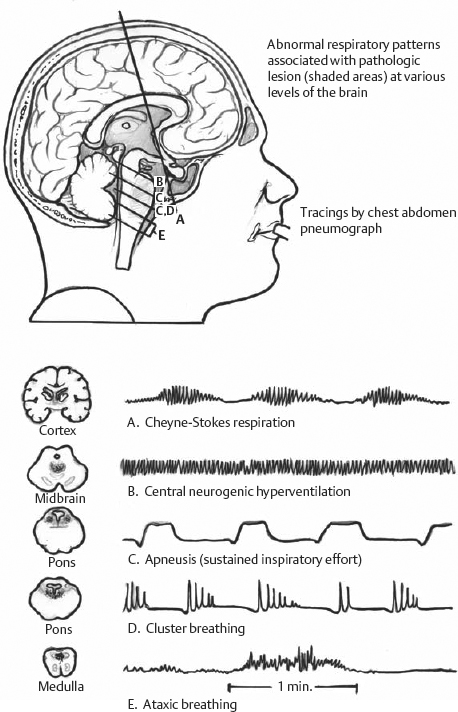

- Breathing patterns can help localize the level of injury (Fig. 15.4).

- Vital signs: Cushing’s triad (hypertension, bradycardia, respiratory irregularity) implies elevated ICP.

Fig. 15.4 Abnormal respirator patterns associated with pathologic lesions at various levels of the brain. Tracings represent chest and abdomen pneumographs.

Neurologic Examination

- A full neurologic examination, including assessment of mental status, cranial nerves, motor skills, and reflexes, as well as a sensory and cerebellar exam, should be performed on all patients.

- Mental status changes range from inattention to coma.

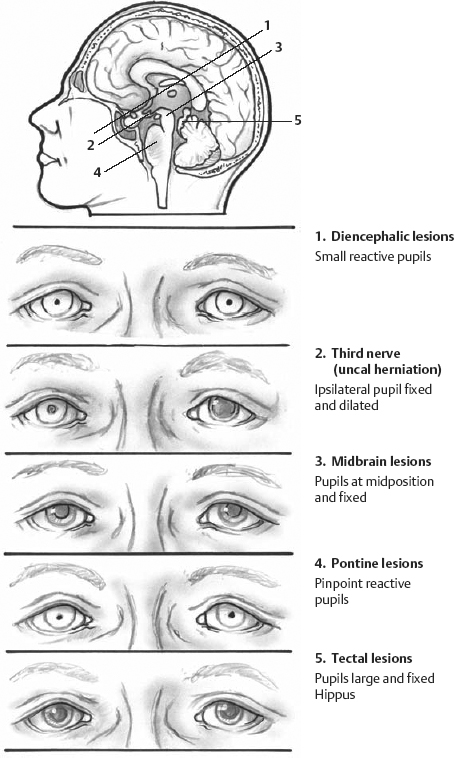

- Cranial nerve examination: Pupillary findings can be localizing (Fig. 15.5). Third nerve palsy (clue to uncal herniation, posterior communicating artery [PCOMM] aneurysm rupture), sixth nerve palsy (nonlocalizing), and papilledema (unreliable finding; the presence of venous pulsations is reassuring for normal ICP, but they are sometimes not seen in normal patients).

- Motor examinaton: Posturing—decorticate or flexor posturing is classically due to lesions anywhere from the cortex to the red nucleus. Decerebrate or extensor posturing is classically due to lesions below the level of the red nucleus. These fixed anatomic localizations of posturing do not always apply. Note that mixed posturing can be seen in one limb, or different types of posturing can be seen on opposite sides of the body.

- Kernohan’s notch phenomenon (long track signs/weakness ipsilateral to the lesion due to herniation and compression of the contralateral cerebral peduncle) is an ominous sign.

Fig. 15.5 Pupillary findings associated with different levels of brain injury.

Differential Diagnosis

- Elevated ICP

- Seizures (tonic-clonic activity can occasionally be mistaken for posturing, and coma due to nonconvulsive seizures could be mistaken for possible ICP elevation)

- Metabolic coma can cause mental status changes. Pupillary reactivity should be spared. Diabetic third nerve palsies are pupil sparing (because the pupil fibers laminate the outside of the nerve, and diabetes causes microvascular infarcts affecting the central nerve fibers).

- A blown pupil in the context of a normal mental status almost never is consistent with herniation. Be on the lookout for medications that cause fixed pupillary dilation (any local β agonist or anticholinergic medication: nebulizers—both ipratropium and albuterol are notorious culprits). Physiologic anisocoria occurs in 10% of the population and is characterized by asymmetric though reactive pupils. New-onset anisocoria requires determination of which pupil is affected. This can be differentiated by examining anisocoria in the light and dark. More prominent anisocoria in the dark suggests a sympathetic lesion (with failure to dilate), whereas more pronounced anisocoria in bright light suggests a parasympathetic lesion (with failure to constrict).

- Meningeal irritation (infectious or sterile) can cause headache, photophobia, nausea, and vomiting and mental status changes (if there is associated encephalitis).

- Migraine can present with acute headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and focal deficits (complicated migraine). Because mass lesions can present with migrainous-type headache, all patients with new-onset migraines should have brain imaging.

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

- Herniation

- Acute hydrocephalus

- Surgical mass lesions

Diagnostic Evaluation

ICP Monitoring

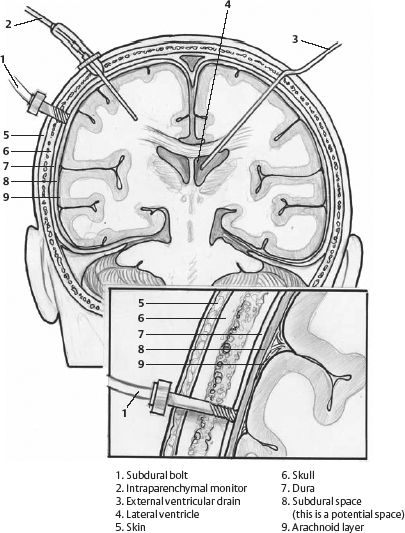

Although there is no level 1 evidence demonstrating the benefit of ICP monitoring, ICP monitoring has been shown in small traumatic brain injury (TBI) series to reduce mortality. A large, randomized study demonstrating improved outcomes with ICP monitoring would require 700 patients at an estimated cost of $5 million to detect a 10% mortality difference.1 The only way to reliably diagnose elevated ICP is to measure it directly. This can be accomplished by performing a lumbar puncture, but this does not allow for continuous ICP monitoring. Additionally, lumbar puncture should not be performed in patients with significant posterior fossa mass lesions, patients with significant midline shift, or patients with third or fourth ventricular hemorrhage. Different ICP monitors are shown in Fig. 15.6 and described below. For all monitors, transducers should be placed at the level of the foramen of Monroe (tragus of the ear) (Table 15.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree