and Héctor H. García3, 4

(1)

School of Medicine, Universidad Espíritu Santo, Santo, Ecuador

(2)

Department of Neurological Sciences, Hospital-Clinica Kennedy, Guayaquil, Ecuador

(3)

Cysticercosis Unit, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas, Lima, Peru

(4)

School of Sciences, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru

Abstract

As detailed in the preceding chapters, clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis are directly related to the localization of parasites within the nervous system, and result from inflammation, mass effects, blockage of the CSF transit, fibrosis, or vasculitis (García and Del Brutto 2005). Inflammation arises from the attack of the host’s immune system to the parasite and is usually found by the time a cyst degenerates. Inflammation is not necessarily a continuous progressive process and occasionally an inflamed cyst may return to a quiescent stage. Moreover, inflammation may also present around old, calcified lesions (Nash et al. 1999). Mass effect occurs when large cysts or cyst clumps located in the subarachnoid space compress neighboring structures, although it may also result from smaller lesions exerting pressure to an adjacent eloquent cerebral area (Proaño et al. 2001). Blockage of the CSF transit is usually caused by intraventricular or subarachnoid lesions or due to chronic scarring resulting from residual fibrosis (Estañol et al. 1983). More rarely, local or remote damage to small- and medium-sized intracranial arteries by a surrounding subarachnoid parasite, or by the inflammatory reaction developed in the subarachnoid space, may result in the occurrence of an ischemic stroke with the resulting clinical manifestations (Del Brutto 2008).

As detailed in the preceding chapters, clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis are directly related to the localization of parasites within the nervous system, and result from inflammation, mass effects, blockage of the CSF transit, fibrosis, or vasculitis (García and Del Brutto 2005). Inflammation arises from the attack of the host’s immune system to the parasite and is usually found by the time a cyst degenerates. Inflammation is not necessarily a continuous progressive process and occasionally an inflamed cyst may return to a quiescent stage. Moreover, inflammation may also present around old, calcified lesions (Nash et al. 1999). Mass effect occurs when large cysts or cyst clumps located in the subarachnoid space compress neighboring structures, although it may also result from smaller lesions exerting pressure to an adjacent eloquent cerebral area (Proaño et al. 2001). Blockage of the CSF transit is usually caused by intraventricular or subarachnoid lesions or due to chronic scarring resulting from residual fibrosis (Estañol et al. 1983). More rarely, local or remote damage to small- and medium-sized intracranial arteries by a surrounding subarachnoid parasite, or by the inflammatory reaction developed in the subarachnoid space, may result in the occurrence of an ischemic stroke with the resulting clinical manifestations (Del Brutto 2008).

A first line of management should target the presenting symptoms of a given patient and pathogenetic mechanisms involved in their occurrence. Therefore, appropriate institution and optimization of symptomatic therapy—antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-edema agents, or surgery—should always precede the use of cysticidal agents (Nash and García 2011). This concept is of particular importance since during the initial days or weeks after the onset of cysticidal drug therapy, symptoms will not improve and could even get worse; this may be dangerous in a given patient with intracranial hypertension or poorly controlled seizures.

As noted, neurocysticercosis is a pleomorphic disease that causes several neurological syndromes and pathological lesions. Therefore, a unique therapeutic scheme cannot be useful in every patient. Characterization of the disease in terms of cysts’ viability, degree of the host’s immune response to the parasites, and location of the lesions are important for a rational therapy (García et al. 2002; Nash et al. 2006a, b). Therapy often includes a combination of symptomatic drugs, cysticidal therapy, and surgery (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

General guidelines for therapy of neurocysticercosis

Parenchymal neurocysticercosis |

Vesicular cysts: |

Single cyst: Albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 3 days or praziquantel 30 mg/kg in three divided doses every 2 h. Corticosteroids rarely needed. AED for seizures |

Mild to moderate infections: Albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 1 week or praziquantel 50 mg/kg/day for 15 days. Corticosteroids may be used when necessary. AED for seizures |

Heavy infections: Albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 1 week (repeated cycles of albendazole may be needed). Corticosteroids are mandatory before, during, and after therapy. AED for seizures |

Colloidal cysts: |

Single cyst: Albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 3 days or praziquantel 30 mg/kg in three divided doses every 2 h. Corticosteroids may be used when necessary. AED for seizures |

Mild to moderate infections: Albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 1 week. Corticosteroids are usually needed before and during therapy. AED for seizures |

Cysticercotic encephalitis: Cysticidal drugs are contraindicated. Corticosteroids and osmotic diuretics to reduce brain swelling. AED for seizures. Decompressive craniectomies in refractory cases |

Granular and calcified cysticerci: |

Single or multiple: No need for cysticidal drug therapy. AED for seizures. Corticosteroids for patients with recurrent seizures and perilesional edema surrounding calcifications |

Extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis |

Small cysts over convexity of cerebral hemispheres: |

Single or multiple: Albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 1 week. Corticosteroids may be used when necessary. AED for seizures |

Large cysts in Sylvian fissures or basal CSF cisterns: |

Racemose cysticercus: Albendazole 15–30 mg/kg/day for 15–30 days (repeated cycles of albendazole may be needed). Corticosteroids are mandatory before, during, and after therapy |

Other forms of extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis: |

Hydrocephalus: No need for cysticidal drugs therapy. Ventricular shunt. Continuous corticosteroid administration (50 mg three times a week for up to 2 years) may be needed to reduce the rate of shunt dysfunction |

Ventricular cysts: Endoscopic resection of cysts. Albendazole may be used only in small lesions located in lateral ventricles. Ventricular shunt only needed in patients with associated ependymitis |

Angiitis, chronic arachnoiditis: No need for cysticidal drug therapy. Corticosteroids are mandatory |

Cysticercosis of the spine: Surgical resection of lesions. Anecdotal use of albendazole with good results |

9.1 Symptomatic Management

Neurocysticercosis-associated seizures seem to respond very well to a first-line AED (Del Brutto et al. 1992a, b). Carbamazepine and phenytoin are the most frequently used drugs, followed by valproate. When choosing the AED, it must be remembered that some patients with a single cysticercus granuloma may develop transient cutaneous reactions with the use of sodium phenytoin (Fig. 9.1) probably related to mechanisms involved in the immune-mediated response of the host to the parasite (Singh et al. 2004). Irrespective of the AED used, good seizure control is almost always the rule in patients with neurocysticercosis, and refractory seizures are rare. However, there is no consensus on the required length of AED treatment in patients with neurocysticercosis. Some authors have suggested that short-term (3–6 months) use of AEDs—while inflammation around a cyst still exists—may be enough. So far, no controlled evidence exists to support this claim and standard guidelines on the use of AEDs should be followed. After seizure remission and appropriate tapering of AED, still 50 % of patients will present further seizure episodes and require reinstalling AEDs for much longer time (Del Brutto 1994). There is increasing evidence favoring the concept that patients who develop calcifications (either spontaneously or as the result of cysticidal drug therapy) are those that will need longer (even lifelong) courses of AED therapy to reduce the risk of relapses in the long-term follow-up (Verma and Misra 2006).

Fig. 9.1

Cutaneous reaction (left) in the back of patient with single cysticercus granuloma (right) occurring 2 weeks after the start of phenytoin therapy

Headache should be appropriately assessed to rule out intracranial hypertension. If no signs of intracranial hypertension exist, common analgesics should be used to obtain appropriate pain control. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs agents has been mostly restricted to corticosteroids, although early reports on the use of dextrochloropheniramine or, more recently, of methotrexate also exist (Agapejev et al. 1989; Keiser and Nash 2003). Acute anti-inflammatory therapy in neurocysticercosis is primarily directed to reduce edema and local inflammation, thus ameliorating intracranial hypertension and decreasing the propensity to further seizures. Corticosteroids also remain the first line of therapy for patients with cysticercotic angiitis to reduce the risk of arterial occlusion with the subsequent development of a cerebral infarction (Del Brutto 2008). The length of corticosteroid therapy varies according to the size of the lesions and the extent of the resulting inflammatory reaction. In many cases, the use of such drugs should be sustained for weeks and perhaps months (more markedly so in patients with multiple large cysts or extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis). As long-term corticosteroid use is associated with unpleasant and sometimes risky side effects, the use of methotrexate has been proposed to decrease the dose and time of corticosteroid therapy (Mitre et al. 2007).

Particular attention should be given to intracranial hypertension, and cysticidal drugs must not be initiated if intracranial pressure is increased as it may worsen it in the short term (Rangel et al. 1987). As previously mentioned, if severe brain edema is suspected or demonstrated by neuroimaging studies—as in patients with cysticercotic encephalitis—corticosteroids must be given as first-line therapy. The choice of a particular drug and the regimen of therapy are not based on controlled studies, but most experts recommend the use of dexamethasone at doses ranging from 6 to 16 mg/day or even higher doses. Using this approach, a rapid response is usually obtained and most patients improve their condition in a matter of hours or a few days. However, symptom relapses may occur at the time of corticosteroid interruption so gradual tapering of these drugs should be considered. If ventricular cysts or hydrocephalus are present or suspected, or if large cyst or a clump of cysts are present, neurosurgical evaluation is mandatory and shunt placement or resection of the lesion(s) may be required (see below).

9.2 Surgical Management

Before the introduction of modern neuroimaging techniques and cysticidal drugs, patients with suspected neurocysticercosis usually went to the operating room for confirming the diagnosis and to get a definitive cure for the disease (Trelles and Trelles 1978). While over the past 40 years less and less patients with neurocysticercosis underwent resection of lesions, surgery still plays an important role in the management of patients with some specific forms of the disease (Sinha and Sharma 2012).

Hydrocephalus secondary to cysticercotic arachnoiditis always requires the placement of a ventricular shunt. The main complication of ventricular shunt is the high incidence of shunt dysfunction. Actually, the high mortality rate (up to 50 %) associated with the development of hydrocephalus due to neurocysticercosis is related to the number of surgical interventions to revise the shunt (Sotelo and Marin 1987). It is probably that long-term corticosteroid administration may reduce the incidence of shunt dysfunction in these cases (Suastegui-Roman et al. 1996). It has also been suggested that an inversion of CSF transit is the most important cause of shunt dysfunction, as it allows parasitic debris to enter the ventricular system. Therefore, the use of a shunt that functions at a constant flow rate—avoiding the entrance of subarachnoid CSF into the ventricular system—could reduce the number of shunt failures (Sotelo et al. 1995).

Surgery is an option for the resection of ventricular cysticerci, particularly those located within the third and the fourth ventricles. While cysticidal drugs destroy many ventricular cysts, the ensued inflammatory reaction that occur as the result of therapy may cause acute hydrocephalus if those cysts are located near the interventricular foramina of Monro or the cerebral aqueduct. In such cases, ventricular cysts may be more safely removed by surgical excision or endoscopic aspiration (Sinha and Sharma 2012). The surgeon must consider the possibility of cyst migration between the time of diagnosis and the surgical procedure, and this must be ruled out by a neuroimaging study before surgery to avoid unnecessary craniotomies (Zee et al. 1984). Shunt placement should follow or even precede the excision of ventricular cysts associated with ependymitis.

Whether spinal cysticerci (located intramedullary or at the spinal subarachnoid space) should be operated or not is still a matter of debate, and it is likely that this question should never be definitively answered based on the rarity of these forms of the disease. Anecdotal cases suggest that medical treatment may be safe and effective (Garg and Nag 1998). However, most experts prefer to refer those patients to the neurosurgeon until further studies are available. For those patients with spinal subarachnoid cysts, the surgeon must have the same precaution than for ventricular cysts, i.e., to perform neuroimaging studies just before surgery, as those cysts may have been moved from the time of diagnosis (Hernández-Gonzalez et al. 1990).

9.3 Specific (Etiological) Management

9.3.1 Cysticidal Drugs

As will be discussed later on, two drugs (albendazole and praziquantel) have been shown to have potent cysticidal effects in humans (Del Brutto 2003). Other drugs, such as metrifonate and flubendazole have been eventually tried in this condition but their use has been promptly abandoned due to side effects or lack of efficacy (Salazar and Gonzalez 1972; Téllez-Girón et al. 1984). Oxfendazole, a benzimidazole molecule with a long half-life, has been shown to cause a significant clearance of muscle and brain cysts in swine after a single-dose trial (Gonzalez et al. 1997); this drug is now undergoing Phase I studies in humans, and if found safe, it may provide a new therapeutic alternative to albendazole or praziquantel. There is also a single report suggesting that ivermectin may be effective in selected cases (Díazgranados-Sánchez et al. 2008).

Praziquantel is a pyrazino-isoquinoline derivative. It affects calcium channels in the parasite’s surface and produces muscle contractions, paralysis, and damage of the tegument (Overbosh et al. 1987). Maximal serum levels are obtained 1.5–2 h after administration and drop rapidly thereafter (Jung et al. 1991). Praziquantel is metabolized in the liver, and size effects are mild and mainly related to gastric disturbances, dizziness, drowsiness, fever, headache, increased sweating, and, less commonly, allergic reactions (reference). For treatment of neurocysticercosis, praziquantel is usually given at daily doses of 50 mg/kg for 2 weeks, with a ceiling of 3 g/day. A single-day course of 75–100 mg/kg divided in three doses given every 2 h has been also described (Corona et al. 1996; Del Brutto et al. 1999), but it seems to be effective in patients with a single lesion but not in those with multiple cysts (Pretell et al. 2001).

Albendazole is a typical benzimidazole compound. It leads to selective degeneration of parasite cytoplasmic microtubules, affecting ATP formation, and also impairs glucose intake, leading to energy depletion and parasite starvation (Rossignol 1981). It binds to tubulin and thus also interferes with parasite cell division. Albendazole is not active by itself and the active molecule, albendazole sulfoxide, results from liver metabolism of albendazole (Castro et al. 2009). Maximal levels are obtained from 2 to 3 h after ingestion, and albendazole penetrates in the CSF better than praziquantel (Jung et al. 1990a). Side effects in humans are mostly related to liver toxicity (increase in liver enzymes), hematological effects, hair loss, and gastrointestinal symptoms (Rossignol 1981). For therapy of neurocysticercosis, albendazole is usually given at daily doses of 15 mg/kg for 1–4 weeks. In the USA, a ceiling of 800 mg/day is frequently used based on FDA-approved doses, while in most other countries, the usual ceiling is 1,200 mg/day (García and Del Brutto 2005).

9.3.2 Trials of Cysticidal Drugs

Cysticidal drugs have been used for therapy of human cysticercosis after Robles and Chavarría (1979) reported the cure of a single Mexican patient with multiple ring-enhancing lesions after a trial with praziquantel. This pioneer report was followed by a number of case series and controlled studies (using historical controls) showing the efficacy of the drug (Botero and Castaño 1982; Sotelo et al. 1984, 1985; Spina-França et al. 1982). Such results prompted clinicians to widely use praziquantel in different forms of the disease. It was then noticed that a few days after the onset of therapy, symptoms increased in a sizable proportion of cases, even with serious adverse effects including intracranial hypertension or death (Wadia et al. 1988). This created confusion among some physicians involved in the care of neurocysticercosis patients, who questioned the benefits of praziquantel and even considered that this drug may actually be deleterious in this setting (Kramer 1995). Meanwhile, albendazole, another cysticidal drug, was first tested in Mexico and then in other disease-endemic countries, and proved effective for destroying parenchymal brain cysticerci, with the advantages of being cheaper and somewhat more effective than praziquantel (Alarcón et al. 1989; Cruz et al. 1991; Escobedo et al. 1987; García et al. 1997; Sotelo et al. 1988, 1990; Takayanagui and Jardim 1992). Some early studies also found a clinical effect on seizure control, with 50–80 % of treated patients being free of seizures compared to 25 % of untreated patients (Del Brutto et al. 1992a, b; Vazquez and Sotelo 1992). However, a couple of controlled studies, published during the 1990s, challenged the usefulness of cysticidal drugs, reporting no significant effect in parasite destruction or in the reduction of seizures (Salinas et al. 1999). Further placebo-controlled studies confirmed the efficacy of cysticidal drugs (as shown in pioneer trials) and settled their actual value in the management of patients with neurocysticercosis (Baranwal et al. 1998; García et al. 2004; Gogia et al. 2003; Kalra et al. 2003).

A review of the published literature including case series of patients with viable parenchymal cysticercosis confirmed by serology and evaluated with neuroimaging studies from 3 to 6 months after the trial shows that praziquantel destroys 57.1 % (95 % C.I. 55–59 %) while albendazole destroys 71.6 % (95 % C.I. 70–73 %) of lesions. In general terms, 50.5 % (95 % C.I. 45–56 %) of patients treated with praziquantel and 53.1 % (95 % C.I. 48–58 %) of those treated with albendazole were free of lesions after therapy (Hector H. García, unpublished data). Although the above numbers incorporate diverse case series with individual biases and likely overestimate the efficacy of both drugs, these overall estimates agree with most reviews on the subject, suggesting that albendazole has a slightly higher cysticidal efficacy than praziquantel.

In order to better understand the apparent discrepancies in the reported trials, we first need to put them in the context of the different types of neurocysticercosis. The clinical evolution of patients with a single parenchymal brain granuloma is extremely different from that of those with multicystic parenchymal disease or extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, and the results of trials in different forms of neurocysticercosis cannot meaningfully be pulled together.

9.3.2.1 Cysticidal Drugs for Therapy of Patients with Viable Brain Cysts

As previously noted, the initial trials on cysticidal drug therapy were performed in patients with established brain cysts, many of them with multiple cysts in the vesicular or colloidal stage (neuroimaging studies showing ring-enhancing lesions with a clear hypodense/hypointense center). This type of lesion will not resolve by itself in the short term and is likely to continue causing symptoms for years (García and Del Brutto 2005). It is unclear whether patients with untreated cystic disease will eventually develop subarachnoid disease years later. For clinicians familiar with this form of neurocysticercosis, the benefits of destroying all cysts under controlled conditions are evident, and thus most experts in Latin America—where viable parenchymal brain cysts is a frequent presentation—are inclined in favor of the routine use of cysticidal drugs (Fig. 9.2). Despite the large body of open controlled studies and case series, only a few years ago, the first double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial demonstrated that viable cysts were not expected to resolve by natural evolution in the short term and that albendazole was associated to fewer seizures with generalization in the long term (García et al. 2004). Of note, the efficacy of albendazole in this trial was only 65 %, and the difference in numbers of partial seizures was not statistically significant.

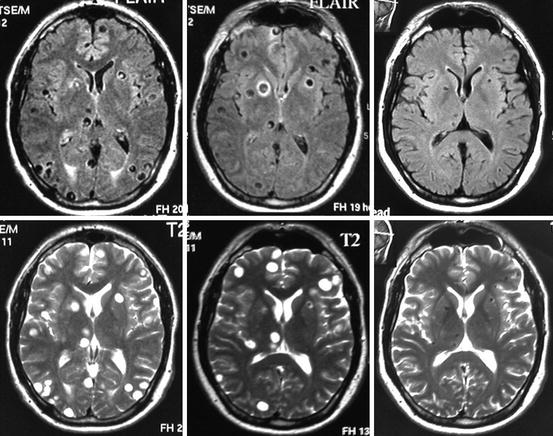

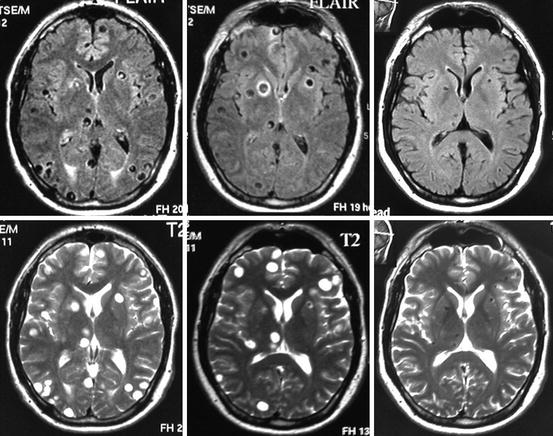

Fig. 9.2

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T2-weighted MRI showing multiple parenchymal brain cysticerci in the vesicular stage (left). Three months after albendazole therapy, most lesions—particularly those located at the occipital lobes—disappeared (center), and 1 year after therapy, all lesions have been resolved and many of them have been replaced by a residual calcification (right)

9.3.2.2 Cysticidal Drugs for Therapy of Patients with a Single Cysticercal Granuloma

In the Indian subcontinent, the most frequent form of neurocysticercosis is a single degenerating brain parasite presenting with recent onset seizures in older children and teenagers (García et al. 2010). This type of neurocysticercosis is also seen in infants and children elsewhere in the world (Del Brutto 2013) and also in residents of non-endemic countries who get exposed to the parasite while travelling or due to close contact with an asymptomatic Taenia solium carrier living in their close environments (Del Brutto 2012; Del Brutto et al. 2012). Therefore, some Indian experts and pediatricians in non-endemic countries were prone to question the benefits of cysticidal drug therapy based on the demonstrated risks of treatment in a disease which they considered mild and of a very good prognosis (Mitchell and Crawford 1988; Padma et al. 1994). In fact, the risks for seizure relapse in patients with a single cysticercus granuloma seem to be below 30 %, strongly associated to cases where a residual calcification is left instead of total clearance of the brain lesion (Verma and Misra 2006). Given the already-established inflammatory reaction with cellular infiltrate and cyst destruction and the fact that most of these lesions frequently resolve without specific treatment, it is reasonable to conclude that cysticidal drugs would have minimal or no effect in this form of neurocysticercosis (Singh et al. 2010). The problem has been mainly generated by the incorrect recognition of a single cysticercus granuloma and by the fact that some studies have probably included patients with both colloidal and granular cysticerci.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree