Management of schizophrenia

Clinical assessment

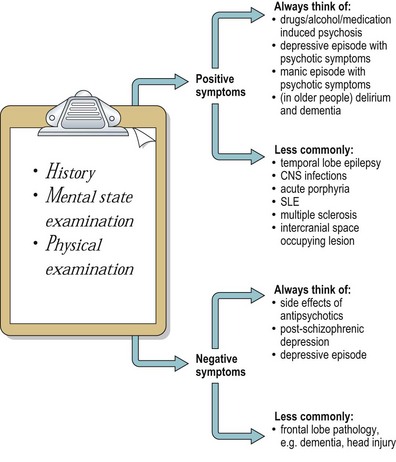

The differential diagnoses shown in Figure 1 should be excluded by history and mental state examination, and by interviewing informants. If there is any suggestion of a drug-induced psychosis a urinary drug screen should be carried out. Apart from this, only those investigations suggested by the history and examination are likely to reveal abnormalities relevant to the diagnosis. There are two exceptions to this. In cases with an unusual presentation, such as onset in middle age, organic causes should be actively investigated. In cases which do not respond to treatment, the diagnosis should be reviewed and a wider range of investigations carried out.

It is important to assess whether inpatient treatment is required. This will depend on a number of factors including the severity of symptoms and their effect on carers, the level of support the patient has in the community, the patient’s insight, the likelihood of them sticking to the advised treatment, and an assessment of risk to themselves or others. The majority of acute episodes can now be managed in the community with input from specialist teams such as CRHT, EIP and AOT (see p. 5). Chronic schizophrenia is usually managed in the community, sometimes after a period of rehabilitation as an inpatient. A small number of patients require long-term care in hospital or in 24-hour nurse-staffed community hostels.

Drug treatment

Acute treatment

The standard treatment of schizophrenia is with antipsychotic drugs (see p. 24). In drug trials of antipsychotics in acute schizophrenia, up to three-quarters of patients receiving active treatment improve, with this improvement usually beginning after 2–3 weeks. Of patients receiving placebo medication, a small proportion will improve but most will either stay the same or get worse. Antipsychotic drugs are particularly effective in reducing positive symptoms.

Rapid tranquillisation

During acute episodes of illness a few patients become so distressed that they pose a serious and immediate threat to themselves or others. There are many possible reasons for this. The risky behaviour may be a direct response to psychotic symptoms, such as a persecutory delusional belief that they are about to be attacked and need to defend themselves. Admission under section can be very distressing, particularly for a patient who has no insight into their illness, and some may respond violently to what they view as an unjustified restriction of their liberty. Intoxication with alcohol and drugs during an acute psychotic episode also makes risky behaviour more likely. Whatever the cause, the initial response should be to reduce the amount of stimulation around the patient, give them some space and a calm environment, listen to what they have to say and provide clear explanations and reassurance. An oral dose of antipsychotic or benzodiazepine should be offered. However, if the situation cannot be managed with these measures it is sometimes necessary to proceed to using rapid tranquillisation. This is medication, usually an antipsychotic or benzodiazepine and often a combination of the two, given intramuscularly. Most units have a local protocol of preferred drugs and doses and the advantages and disadvantages of the three most commonly used drugs in the UK are summarised in Table 1. In order to administer the injection the patient may need to be restrained. This is a potentially dangerous procedure for the patient, and should only be done by appropriately trained staff. The aim is to reduce distress and arousal, not to send the patient to sleep. Following rapid tranquillisation, there is a risk of hypotension, arrhythmias and cardiorespiratory depression, so pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate should be monitored regularly.

Table 1 Drugs given intramuscularly for rapid tranquillisation

| Lorazepam (benzodiazepine) |

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|