Managing Crises and Emergencies in the Course of Treatment

AVA T. ALBRECHT

KEY POINTS

Life-threatening emergencies in the field of child and adolescent psychiatry are uncommon. When they occur, almost half are for suicidal threats or behavior, and nearly a quarter for violent or destructive behaviors, symptoms that often occur in depression.

Additional crises include nonadherence, treatment refusal, sudden deterioration, school refusal, family instability, and peer and school problems.

Have a means of being contacted urgently for crisis situations.

Assess the nature of the crisis or emergency over the telephone first.

Counseling and reassurance may be all that is needed to stabilize a crisis.

Refer to the emergency room if there is concern for suicidality or dangerousness and the child cannot be seen in a timely manner, using emergency medical services or police if necessary.

Distinguish between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempt (consider intent, lethality, and chronicity of behavior).

Assess medication compliance at every visit.

Coordinate with other providers caring for the child (e.g., therapists, school counselors, case managers, pediatricians).

Address family crises (e.g., divorce, violence, financial instability, abuse), which can precipitate a deterioration.

Family psychopathology may require referral of parent or parents for treatment.

Assess academic functioning and facilitate appropriate school-based services.

Monitor substance use.

Introduction

Life-threatening emergencies in the field of child and adolescent psychiatry are uncommon. When they occur, almost half are for suicidal threats or behavior, and nearly a quarter for violent or destructive behaviors.1 Emergencies and crises that present during the course of treatment often are related to the perceptions of the persons involved in the supervision of the child (usually parents, but school personnel and other providers as well), and thus they may be secondary to circumstances apart from the child, such as stressors within the family. Although crises can occur with any psychiatric illness, they are common in depressive disorders, particularly suicidal behaviors. The prevention of crises and emergencies is facilitated by a comprehensive evaluation of patients and their environment, looking for risks, close management, and follow-up during the treatment phase, and timely response to new problems or new stressors. Table 15.1 outlines various crisis situations that can occur in the treatment of depressed children and notes potential adverse outcomes if they are not addressed judiciously.

TABLE 15.1 CRISES, POTENTIAL ADVERSE OUTCOMES, AND INTERVENTIONS | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unquestionably, suicidal behaviors, homicidal ideation, aggression, and violence are the most urgent crises to manage. Other crises that are often encountered include running away from home, manic switching, sudden deterioration, the emergence of psychotic symptoms, school crises (e.g., dropping out), family conflict (e.g., abuse), and substance use. Timely intervention is important because these situations can spiral out of control for both patient and family leaving them feeling hopeless and overwhelmed, and potentially resulting in worse outcomes. Crises may be directly related to the child’s depressive illness or owing to other factors. Additionally, because the treatment for depression typically extends into a year or more, new crises can present that were absent at the start of treatment.

Phone contact with the concerned party (e.g., parent, patient, school professional) is the simplest and quickest method to avoid and manage crises. The clinician must be available to respond to urgent calls, so that early telephone intervention can be initiated, and the clinician’s call policy should be known to the patient at the start of treatment. The nature of the crisis and the level of risk can often be assessed through the phone call. To evaluate if an emergency exists, it is important to clarify the exact circumstances and antecedents. Some crises can thus be managed over the telephone with support and counseling and a plan for follow-up. Other crises may require bringing the child or adolescent to the emergency department. In some countries or areas with well-developed community mental health services, specialist teams can conduct home visits, evaluate the crisis, and provide appropriate treatment and support without the need to use emergency department services. Almost always a follow-up appointment is needed as soon as possible. The more common crises are discussed in the paragraphs that follow. The word child is used to refer to children and adolescents unless specified otherwise; parent is used to mean parents, guardians, or caregivers.

SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR

Depressive disorders carry an increased risk for suicidal behavior, which ranges from ideation, through threats and attempts, to completion. Both the initial and ongoing assessment of depression should always include an evaluation of suicide risk (see Chapter 3). Suicide attempts and completion are among the most significant consequences of major depressive disorder (MDD) in youth, with approximately 60% reporting having thought about suicide and 30% actually attempting suicide.2 Prepubertal children are at lower risk for suicide attempts than adolescents, with completed suicides becoming gradually more frequent with increasing age, even within adolescence.3 In the United States, suicide is the third leading cause of death for both the 10 to 14 years and the 15 to 19 years age groups, representing 7.2% and 11.8% of all deaths, respectively.4 A recent review by Kloos et al.5 examines the nature of prepubertal suicidality, the relative dearth of information regarding the screening of this age group, and risk factors for suicide attempts, noting that even in the younger age groups, screening should take place for suicidal behaviors, especially in the presence of depression. Family psychopathology appears to be a contributing risk for childhood suicide that continues into adolescence.3,5,6

Assessment of suicide risk, particularly suicidal intent, is complex and unreliable. The Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment (C-CASA), a standardized suicidal rating system developed for the evaluation of suicidality in antidepressant trials, is reliable (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.89) and transportable, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has mandated its use in psychotropic and other drug trials.7 Although this is a research instrument, it may also be useful in clinical practice, at least by standardizing the terminology. Appendix 15.1 lists C-CASA definitions and examples.

A suicidality assessment should be done for all patients with depression, encompassing both a risk assessment and an evaluation of the safety systems present or needed to minimize risk. Although ongoing assessment of suicidality is obviously required when present at the start of treatment, it is not always evident that it requires continued reassessment even if absent at the outset. A review of symptoms during follow-up visits should include questions regarding the presence or absence of suicidal thoughts. This is particularly important with the initiation of pharmacotherapy, discussed in detail in Chapter 6. Should suicidal behavior arise during the course of treatment, knowledge of the initial presentation will guide an assessment of any additional interventions. The presence of suicidal behavior may come to the treatment provider’s attention via a telephone call or during a follow-up visit. If through a phone call, an initial assessment over the phone is necessary to determine if the child needs to be brought to the emergency department for immediate evaluation or to the office or clinic for further assessment (which also depends on how soon the child can be seen, the judged level of acute risk, and the level of supervision; when in doubt, an emergency department referral is the safest option). Based on knowledge of the patient and the parent’s ability to provide close monitoring of the child, a decision to evaluate in the office may be made. If a suicide attempt is reported, the most prudent action would be an immediate evaluation in the emergency department to determine if hospitalization is warranted. If the parent is not able to transport the child to an emergency department safely, emergency medical services and/or police can be contacted for assistance. Supervision of the child should be continuous until help arrives. Nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior may not require an emergency assessment (see further discussion later).

Various factors need to be considered when assessing suicide risk. The risk increases if these situations are present:

A history of suicide attempts

Comorbid psychiatric disorders (e.g., disruptive disorders, substance abuse)

Impulsivity and aggression

Availability of lethal agents (e.g., firearms)

Exposure to negative events (e.g., physical or sexual abuse, violence)

Substance abuse

Family pathology and family history of suicidal behavior

Hopelessness

Psychosis

Reduced level of support

The availability of lethal means of suicide should be assessed because firearms, suffocation, and poisoning were the top three methods used in the United States for suicide in both the 10-to-14 and the 15-to-19 age brackets,4 with suffocation the top choice for the younger age group and firearms for the older group (the relative frequency of the means used for suicide vary from country to country; see Chapter 24).

Keep in mind that adolescents may not initially reveal thoughts of suicide, which will probably need to be drawn out using indirect questions (e.g. “Do you ever have thoughts that you’d rather not live or wish you’d never been born?”). Acknowledgment of more “passive” means of dying or suicide are more readily elicited and can further enable accurate reporting to questions about intent or plans. Here are some questions for assessing suicidal ideation:

Did you ever wish you weren’t born?

Did you ever wish you could disappear?

Did you ever wonder about death?

Did you ever consider hurting yourself?

Did you ever have thoughts about killing yourself?

Did you ever think of a plan to kill yourself?

What sort of plans have you considered?

Do you want to die?

What keeps you from killing yourself?

Further suicide assessment should include questions about whether or not the child has considered a plan in the past or more recently, as well as an assessment of suicidal intent, which examines the desire to die versus to live. As noted earlier, access to guns or medications should be ascertained from the child and the parent and eliminated. Ultimately, if a child presents with a specific plan, and with the intention to carry the plan out, hospitalization is probably warranted. With lesser degrees of intent, the need for hospitalization depends on the balance of risk and protective factors, as well as the ability of parents to provide round-the-clock supervision while the treatment plan is adjusted.

In addition to hopelessness, hostility, negative self-concept and isolation are also proposed as psychosocial factors to consider when assessing risk.8 Higher risk periods for suicide occur following discharge from hospital, after a medication change, or during an absence of the therapist. With an adequate support system in place, a child may be safely monitored as an outpatient with daily phone calls and weekly, or more frequent, visits. Once a child has been in treatment for some time, knowledge of the child will make it easier to manage these eventualities.

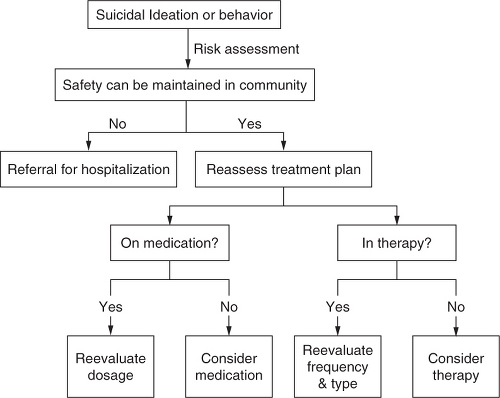

When onset occurs during the course of treatment, the effectiveness of the treatment ought to be reviewed. Emergent suicidality may be owing to a new disorder, a side effect, or lack of efficacy of the medication. If the suicidal ideation is new and treatment was recently started, continuation of the treatment plan (with adequate monitoring and safeguards, such as close supervision at home and school, regular telephone contact, and more frequent office visits) may simply be required. The suicidal behavior can also be contrasted with the symptoms present during the evaluation phase to determine if the treatment is working. If symptoms have been in remission, the occurrence of suicidal behavior may be a signal that a relapse is occurring and medication or therapeutic modality require adjustment, such as increased medication dosage, change of medicine, increased frequency of therapy sessions, or changes to the modality of therapy (e.g., family conflicts as a precipitant for suicidal behavior may be a signal for the use of family therapy). Figure 15.1 presents a basic overview of the management of a suicidal patient.

NONSUICIDAL SELF-INJURY

Suicidal behavior needs to be differentiated from other types of self-harm—often identified as nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), deliberate self-harm, or self-injurious behavior without suicidal intent—whose goal is hypothesized to be relieving negative emotions (assessing the intention in specific cases is often very difficult). This behavior most commonly involves repetitive self-cutting to relieve anger, distress, or loneliness rather than seeking to end one’s life.9 Nonsuicidal self-injurious acts can occur in suicidal individuals as well. Superficial cutting or burning of the skin often occurs without suicidal intent, although such actions can result in emergency department referrals. Intentional self-injury typically serves to reduce tension in the short-term, with many individuals who practice such

behaviors describing a feeling of relief of emotional pain as a consequence. More common in adolescents than in children, nonsuicidal self-injury is often associated with mood disorders, in particular depression. Most studies on NSSI have been done in the adult population. Efforts to better understand NSSI and its relationship to suicide attempts in adolescents are ongoing. Brunner et al.10 examined differences between occasional (one to three times per year) and repetitive forms (four or more times per year) of self-injurious behaviors in a group of German adolescents. They found that social factors, like school-related and family-related variables, demonstrated a strong association with occasional self-injurious behavior and that psychological factors seemed to be more strongly associated with repetitive self-injurious behavior. Suicidal behavior (suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) was associated with both the occasional and repetitive forms of self-injurious behavior (although more strongly in the repetitive type). Lloyd-Richardson et al.11 investigated a community sample of U.S. adolescents for self-injurious behavior and found that some form of it was endorsed by 46% of adolescents within the previous year. The 28% who endorsed more moderate or severe forms of self-injurious behavior was the group more likely to have a history of psychiatric treatment and past or current suicidal ideation. The most common reasons cited for self-injury were “to try to get a reaction from someone,” “to get control of a situation,” and “to stop bad feelings.” In a study of adolescent inpatients, Nock et al.12 found that those who engaged in NSSI reported more frequently doing so to regulate their own emotions rather than to influence the behavior of others. A review13 found a prevalence of NSSI between 13% and 23% among studies that included only adolescents. Adolescents from various samples and levels of psychopathology reported engaging in NSSI to regulate—typically to decrease but sometimes to increase—emotions; MDD occurred in 42% to 58% of patients with NSSI; if all depressive disorders were included, up to 89% of the participants engaged in NSSI.

behaviors describing a feeling of relief of emotional pain as a consequence. More common in adolescents than in children, nonsuicidal self-injury is often associated with mood disorders, in particular depression. Most studies on NSSI have been done in the adult population. Efforts to better understand NSSI and its relationship to suicide attempts in adolescents are ongoing. Brunner et al.10 examined differences between occasional (one to three times per year) and repetitive forms (four or more times per year) of self-injurious behaviors in a group of German adolescents. They found that social factors, like school-related and family-related variables, demonstrated a strong association with occasional self-injurious behavior and that psychological factors seemed to be more strongly associated with repetitive self-injurious behavior. Suicidal behavior (suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) was associated with both the occasional and repetitive forms of self-injurious behavior (although more strongly in the repetitive type). Lloyd-Richardson et al.11 investigated a community sample of U.S. adolescents for self-injurious behavior and found that some form of it was endorsed by 46% of adolescents within the previous year. The 28% who endorsed more moderate or severe forms of self-injurious behavior was the group more likely to have a history of psychiatric treatment and past or current suicidal ideation. The most common reasons cited for self-injury were “to try to get a reaction from someone,” “to get control of a situation,” and “to stop bad feelings.” In a study of adolescent inpatients, Nock et al.12 found that those who engaged in NSSI reported more frequently doing so to regulate their own emotions rather than to influence the behavior of others. A review13 found a prevalence of NSSI between 13% and 23% among studies that included only adolescents. Adolescents from various samples and levels of psychopathology reported engaging in NSSI to regulate—typically to decrease but sometimes to increase—emotions; MDD occurred in 42% to 58% of patients with NSSI; if all depressive disorders were included, up to 89% of the participants engaged in NSSI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree