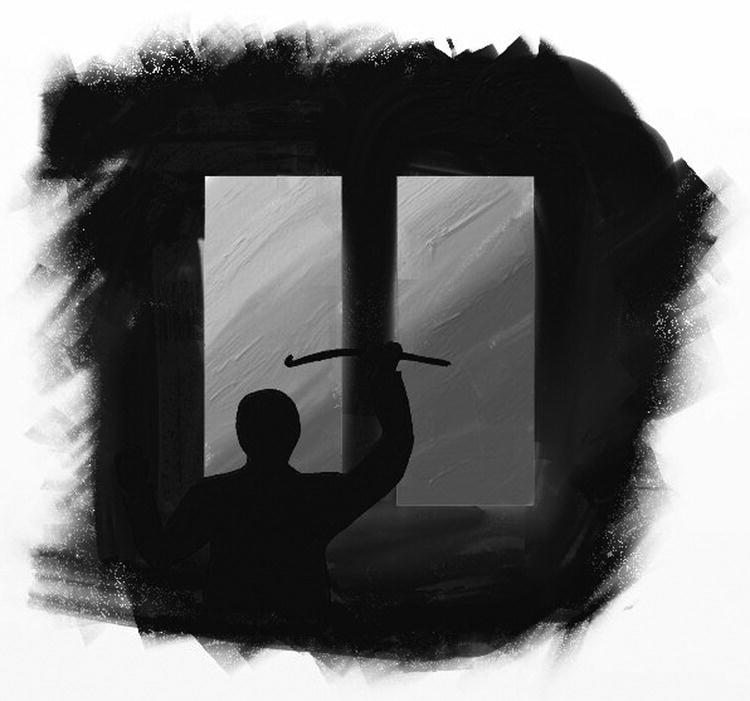

13 Maria Loades, Sarah Clark, and Shirley Reynolds Intrusive negative thoughts play a core part in maintaining and exacerbating children’s fears and their difficulties with low mood. A range of strategies have been developed that can be used with children and young people to help them identify, manage, or reduce their negative thoughts. Children’s cognitive development is highly variable and individual; therefore therapists may need to try a range of strategies with each child before finding the one that works best for the individual child or young person (see Chapter 5 for more details on development). In addition, these strategies are likely to be much more useful and engaging if they are adapted to suit the individual needs and interests of each child. In this chapter we describe four different specific CBT techniques, drawn from Sburlati, Schniering Lyneham and Rapee (2011), that are designed to help children overcome or tackle their negative thoughts. We also provide examples of each strategy being used. These examples are offered in order to illustrate the techniques, help clinicians relate them to clinical work, and establish a basis for the creative adaptation of these techniques to each client’s specific circumstances and needs. In order to illustrate the use of the techniques described, we will present the following two cases: The images that go through our minds are a key part of our cognitive architecture. They can be brought to mind deliberately, for example when we try to remember a happy event (such as a birthday party or a holiday), or they can come to mind unintentionally. Although we are sometimes unaware of their occurring, images can capture key emotions, memories, and beliefs and have a powerful impact on our mood and well-being. Images are often visual but can consist of (or include) sounds, smells, and movements. Fear is often linked to strong and powerful images that, for many people, evoke more emotional content than verbal descriptions of their fears. Therefore, if therapists do not access their client’s images, they may miss their most significant thoughts. To illustrate, compare the image of a dog that a child who fears dogs might entertain with the image of a dog that is likely to be generated by a child who does not have a fear of dogs. These contrasting images are likely to include movement (say, tail wagging or biting) and sound (growling or barking) in addition to visual elements related to the dog’s size, color, and shape. Similarly, a child frightened of needles and injections may associate these objects with visual images of frightening places (hospitals) and people (doctors and nurses), of themselves or their parents in pain or distress, or of the needle or injection itself. Because our mental images have a powerful impact on emotions, they can be a useful tool for attenuating emotional distress. In therapy, positive images can be used in two ways. First, the therapist can work with his/her client to transform negative, unhelpful images – for example, an image of a scary monster under the bed – into positive or benign images – for example, a friendly cartoon character (Deblinger and Heflin 1996). Second, the therapist can work with his/her client to create new positive images – for instance, an image of the self as successful and competent – in order to help that client counteract his/her key psychological difficulties – for example, to replace negative images and beliefs about the self as useless. Therefore, rather than trying to eliminate negative images directly, therapy tends to build and develop new positive images that may replace them. Clients do not always describe their images spontaneously, but therapists can elicit them. Standard cognitive techniques (see Chapter 12) can be adapted so as to include questions targeted specifically at eliciting imagery (Hackmann, Bennett-Levy, and Holmes 2011). The following excerpt from a session with Katie illustrates this procedure: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Such questions can be followed by further questioning designed to explore the imagery more closely. This questioning can focus on physical features of a visual image (“What/whom else can you see there?” or “What color are her shoes?”). Therapist: Katie: Depending on the child’s age and developmental level, it may be appropriate for the image to be drawn by the young person (see Figure 13.1 for an example). Figure 13.1 Image of the imagined intruder. © Christopher Jacobs. Reproduced with permission. The focusing questions can then be developed further, so that more of the emotional content emerges: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: When the image has been described, the therapist can then help the young person explore what it means. Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Once the image has been elicited and its impact understood, rather than proceeding to challenge it, the next step is to collaboratively develop a transformation of the image, on the basis of what would have to change within the image for it to be less distressing. Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: Katie: Therapist: The final step is to introduce this transformation into the image (which could be done creatively, through role-play or drawing; see, e.g., Figure 13.2) and then rehearse the re-scripted image. Figure 13.2 Transformed image of the night-time “intruder.” © Christopher Jacobs. Reproduced with permission. Transforming the frightening image is a process similar to cognitive restructuring (Chapter 12), although it focuses on nonverbal content and, rather than identifying evidence for and against the image content, the process concentrates on developing and elaborating a new image that is less distressing. The new image need not be realistic, provided that it feels helpful, gives a sense of control over the negative imagery, promotes image acceptance, and enables the client, rather than dismissing it, to “play” it through, mentally, past the worst point, facilitating a sense of resolution. Positive images can also be developed in the absence of negative imagery. This can be useful for managing negative affective states, for reducing negative affect (for instance by inducing relaxation, which is a low negative state), and for promoting self-compassion and/or a sense of self-efficacy. For example, Gilbert (2009) has introduced the concept of self-compassion as a helpful way of countering self-criticism and feelings of isolation. In the session, the young person is encouraged to bring to mind a real or an imaginary character who personifies compassion and nurturing. This task involves brainstorming the qualities of an “ideal” nurturer, focusing on fostering feelings of warmth, acceptance, and compassion, then generating an image of what this figure would look like – its physical features and facial expression, its sensory characteristics (e.g., tone of voice, smell), its knowledge or wisdom – and finally exploring what being close to that figure would feel like. The compassionate character may be given a name or identity. In subsequent sessions the young person is encouraged to bring the compassionate image to mind and to focus on positive emotions that are associated with the image – such as warmth, safeness, and soothing (Lee 2005). When the image has been developed in therapy sessions, the young person is encouraged to bring it to mind outside sessions, when (s)he has a negative automatic thought or experiences distress. Imagery can also be used to develop positive feelings about the self and the future. An example would be helping the young person develop a positive image of the self that the young person has not yet become. In such cases the image represents a positive self-image, which can be brought to mind and used in interpersonal problem-solving situations. The following extract illustrates how this technique was used successfully with Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Ok, Francis, I’ll give you a few minutes to think, so let me know when you have a picture on your screen of your future most developed self, yourself at your peak. [pause] Francis: Therapist: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Now that the therapist has developed the physical image, she starts to move onto questions to explore the emotional state of the future most developed self (FMDS) image. Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis: Therapist: Francis:

Managing Negative Thoughts, Part 2: Positive Imagery, Self-Talk, Thought Stopping, and Thought Acceptance

Introduction

Positive Imagery

Key features of the competency

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Managing Negative Thoughts, Part 2

So when you heard a noise that evening, what went through your mind in that moment?

Ummm, I thought it was a burglar.

Ok, so you thought it was a burglar making the noise. Was there a picture of that in your mind?

Ummm, I’m not sure. Like what do you mean?

Like could you paint me a picture, using words, of what you thought was happening when you heard that noise.

Well, I thought … that the burglar was outside, trying to open the front door.

Mmmhmm … can you tell me what the burglar looked like in your mind?

Yeah, he was like a really big man, wearing all black clothes, with a big axe in his hand.

What did you think was going to happen next?

Ummm, I thought that he was going to break through the window.

Ok, so you thought he would break through the window, and then?

Then he would come running into the house …

Gosh! How did that picture in your mind make you feel?

Well … scared and worried.

It does sound like a really scary picture to have in your mind. What did it make you do?

I had to check if mum and dad were ok, and wanted to be close by them. I asked dad to check if the door was locked.

Ok, Katie, so when you have that scary picture in your mind of that big man with the axe, what does it make you think about: yourself or other people?

Ummm … I’m not really sure …

Well, if I had a scary picture in my head, I might start to worry about myself, or I might start to worry about other people, or both. Does that happen for you?

Oh, I worry about mum and dad, and me, and that we’ll get hurt. That’s why I always stay near to them.

Ok, so that picture in your mind makes you worry about yourself and mum and dad getting hurt.

So this really scary picture in your mind, Katie, what do you think would have to change to make it less scary for you?

Ummm, I don’t know.

If we could change the story that comes up in your mind when you hear those scary noises at night, what would be a story that wouldn’t be scary for you?

Well, mum once told me that there are lots of animals around in the night and that they make lots of noises, so maybe a story about the animals?

What kind of animals do you think move around in your garden at night?

I think that there was a hedgehog once …

Ok, so we could make a story about a hedgehog…what do you think this hedgehog would be up to in the night?

Ok, Francis, we are going to do an imagery exercise now. Ideally, it would be good if you could keep your eyes closed throughout the exercise. But, if you don’t want to close your eyes, then maybe you could pick a spot on the wall opposite you to stare at.

Ok. [closes his eyes]

Are you ready to begin?

Yep. [nods]

Ok Francis, while you are sitting there with your eyes closed, I would like you to imagine a TV screen in front of you. On this screen, I would like you to place an image – a picture of your future most developed self. Let me explain. This is a picture of yourself that you have not yet become. This is you. This future self has all the knowledge, coping, and experience necessary in life, to be fully in charge of himself in his life, and able to choose what he wants and how he wants to live his life.

Mmmm, ok … I’m not sure I know what you mean …

Like yourself as you most want to be in the future, yourself at your peak.

Oh, I think I get it now.

Mmm, I think I have it.

Great, excellent. Now, let’s spend a little time building this up into a clearer picture of your future most developed self.

Tell me, what do you notice about your future, most developed self that is possibly different from how you are today? Is he doing anything? Standing? Sitting?

I can see me but older, maybe 25. Sitting down.

Ok, great, let’s see if we can add in some more details. What is his hair like?

Kind of short and neat, shorter than now.

And his face?

Well, like now but his skin is way better, no spots!

What is your future most developed self wearing on his top half?

Like a button up shirt.

What color?

It’s like a blue color, pale blue.

Buttoned up to the top?

Mmmm … top button open, like casual. Sleeves rolled up too.

Ok, great, what is your future most developed self wearing on his bottom half?

Ummmm … like jeans I think.

Now Francis, take a look at his face. What expression can you see?

Yeah … He looks happy, and quite chilled, I think …

So he looks happy, chilled. How does your future most developed self feel?

Ummm … this is tricky …

You’re doing a great job so far. How do you think he feels?

I think he feels happy and in control.

Ok, so happy and in control. What tells you this? How can you see it?

Well, he’s like sitting back in the chair, his body looks relaxed, and he looks healthy, tanned and toned.